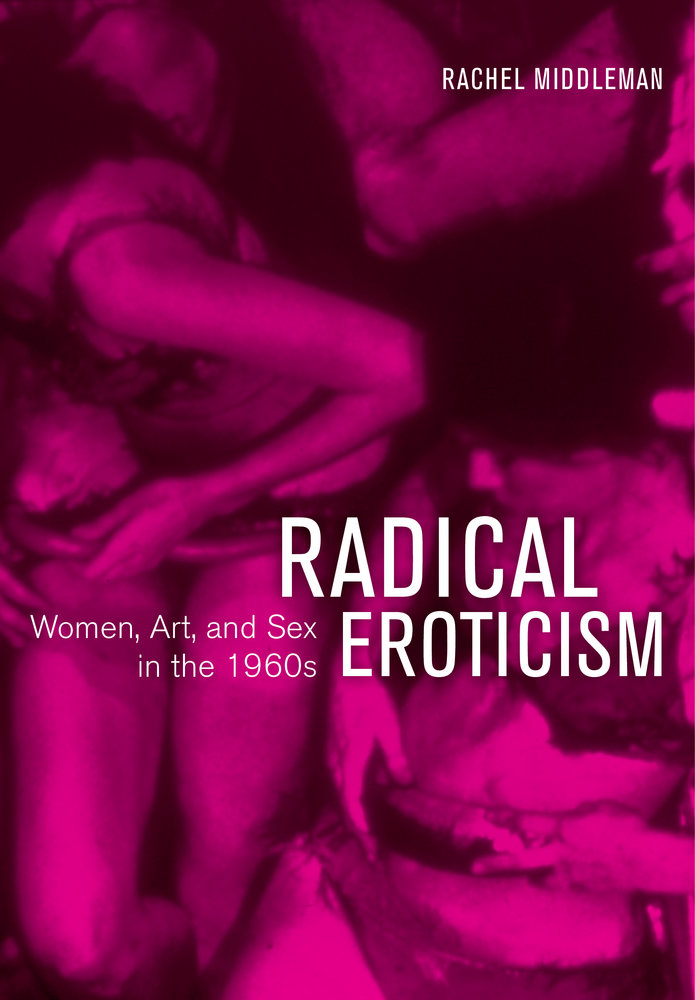

Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s

Rachel Middleman

Rachel Middleman

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018; 280 pp.; 62 color illus; 46 b/w illus. Hardcover $65.00 (ISBN: 9780520294585)

During the sexual revolution of the 1960s, erotic art in the United States fueled debates about sexual liberation, the nude body, and the gendered dynamics of visual pleasure; however, art-historical literature on the genre is scant, particularly on art made by women.1 Rachel Middleman’s Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s provides an important history of the overlooked contributions of heterosexual women to the discourse of eroticism in contemporary art. By closely examining the works of Carolee Schneemann, Martha Edelheit, Marjorie Strider, Hannah Wilke, and Anita Steckel, Middleman demonstrates how their practices emphasized sexuality in ways that disrupted normative assumptions about gender and reimagined eroticism across a broad spectrum of styles, media, and artistic processes. With these five case studies and an extensive introduction, Middleman provides an insightful examination of the exhibition and critical reception of erotic art, laying the groundwork for understanding the social context and political stakes of the approaches of women artists to eroticism in a decade of expanding forms of artistic practice, the demise of modernist aesthetics, and the rise of the feminist art movement.

The book is organized around individual artists; however, the inclusion of exhibitions of erotic art creates continuity among the chapters. In the introduction, for example, Erotic Art ’66 at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1966 sets the stage for Middleman’s analysis of the ways in which erotic art cut across categories of medium and style and threatened the supposed autonomy of art by stressing the role of sexual desire. Furthermore, as this exhibition of twenty artists featured only one woman, Marisol Escobar, Middleman shows how female artists were often marginalized in the genre of erotic art through lack of representation and biased reception. Middleman demonstrates the threat that protofeminist works such as Marisol’s posed to sexist notions about female artists and subjects, as well as traditional conceptions of erotic art, through an examination of the ways in which critics relied on stereotypes of female narcissism by conflating the artist and the erotic bodies she depicted, instead of focusing on the radical defiance of her work from normative representations of gender and sexuality (2–8). Like the other female artists in Radical Eroticism, Marisol claimed a space for the exploration of gendered embodiment and female sexual pleasure. However, unlike Middleman’s case studies, Marisol’s work and its framing by critics and curators was complicated by her Latin American identity and viewers’ expectations of her exoticism.2

In the first chapter, which centers on Schneemann, Middleman analyzes the artist’s scandalous body art performance, Meat Joy (1964), and experimental film Fuses (1964–67), to show how the artist “claimed explicit male/female sex for socially redemptive erotic art and away from its commercial exploitation in pornography and the exclusive purview of heterosexual men” (63). Meat Joy, which featured four bikini-clad male/female couples who interacted with raw chicken, fish, and paint, as guided by a “serving maid” in an apron who provided meat and other materials to the performers, so disturbed one male audience member during the first performance that he tried to strangle her as three female spectators ran to her rescue. The maid’s unique role, as Middleman points out, reinforced the female authorship of the event and subverted expectations of female subservience as she directed the performers’ actions (43). Fuses, which presented viewers with collaged scenes of Schneemann’s daily life, including sex with her male partner as her cat watches, has frequently battled censorship since its initial screening in 1968. Middleman asserts that Schneemann expressed “her experience of sex while at the same time unsettling conventions of commercial pornographic films and troubling expectations of women” by splicing together, reversing, layering, and superimposing the frames of the film in ways that disorient viewers and transgress normative representations of heterosexual sex (60). Building on writings about Schneemann by Amelia Jones and Anette Kubitza, Middleman ultimately argues that Meat Joy and Fuses “engaged with the intersubjective complexities of representing eroticism as a way to communicate with her audiences and provoke their consciousness” (61).3

Chapter two, which centers on the erotic art of Martha Edelheit, opens with her 1966 solo exhibition at Byron Gallery, which led conservative critics to characterize her as “an obscene woman” and simultaneously inspired Allan Kaprow’s praise of her erotic work as among the most radical of its time, certainly more so than her straight male counterparts (64–65). Middleman analyzes how Edelheit’s erotic multimedia practice broke with the imperatives of modernist art and defied the social prohibition against women making sexually explicit images, arguing that she “asserted women’s right to sexual expression and drew attention to the long history of sexism,” while “disrupt[ing] aesthetic conventions and social norms of heterosexuality” (65). Middleman surveys Edelheit’s work across the 1960s—from paintings that refused to be contained by the frame and assemblages of mannequin parts to painted watercolors of sadomasochistic sex scenes and life-size paintings of male nudes—and closely examines its exhibition and reception, exploring the complex factors that led to its marginalization by both conservative and feminist critics. In particular, she looks at how representations of the erotic male nude and carnivalesque scenes of bondage and domination drew unfavorable reactions resulting from their associations with male homosexuality and violence against women (84–86). This is a particularly astute examination of Edelheit’s biased reception, one that exposes how her protofeminist work critiques binary constructions of gender and disturbs normative sexual practices. Although much more could be done with the aesthetics of sadomasochism in Edelheit’s works, Middleman provides an important foundational study of a significant yet under-recognized artist.

The third chapter also looks at an artist who, until relatively recently, was overlooked in the literature on art of the 1960s. Marjorie Strider, like many of the women who contributed to Pop art, has been virtually ignored in histories of the genre, despite her representation in prominent exhibitions at Pace and Dwan galleries and inclusion in Lucy Lippard’s book Pop Art (1966). Strider was further discounted by feminist art history because her eroticized Pop images were seen as celebratory of sexist mass culture. Building on Kalliopi Minioudaki’s recent scholarship on female Pop artists, Middleman shows how Strider deployed commercial images of women, especially the pinup girl, to critique the manipulation of female bodies in service of male heterosexual desire.4 Middleman is reticent to claim Strider’s bikini girls as an “empowering female gesture” (as Minioudaki does), given that they were regularly placed in the context of erotic art exhibitions that habitually objectified women, yet she does read the works as proto-feminist in the ways that they confront viewers with the constructed and clichéd nature of these images (104–5). Portraying breasts and buttocks that awkwardly protrude from the frame, Strider disturbed both the emphasis of modernist art on medium specificity and the slick eroticism of a Playboy centerfold. Her feminist commitments, however, come into even greater focus through Middleman’s analysis of Strider’s lesser-known conceptual and performance works of the late 1960s. Taking gilt frames to the streets in her collaborative Street Works series (1969) or having nude models wear her Frames Dress (1969) in public, Strider investigated the ideological power of the frame and the contingency of viewing in ways that anticipated feminist art of the 1970s.

Chapter four offers a reexamination of the sculpture of Hannah Wilke in the context of erotic art, as well as period debates about abstraction and figuration. In particular, Middleman discusses Wilke’s work in relation to Lippard’s concept of “abstract eroticism,” or sensuous abstract form, which is erotic in a non-explicit and nonfigurative manner. Much like David Getsy’s recent book Abstract Bodies, which explores how abstract sculpture of the 1960s provided a “less determined and more open way of accounting for bodies and persons,” Middleman shows how Wilke’s sexually ambiguous sculptures circumvented gender binaries and stereotyped conceptions of the feminine (126).5 Departing from interpretations of her “vaginal iconography” as essentializing representations of the female sex, Middleman demonstrates how Wilke’s sensual latex and terra-cotta sculptures framed gender and sexuality as mutable and multiple rather than fixed and binary. Middleman further argues that Wilke’s sculpture from the 1960s “challenged the pseudo-objectivity of formalism and figurative erotic art in ways that prefigure later feminist theories,” and in the process defied “erotic art’s traditions and conventions of heterosexuality that historically had been defined by men” (118). This is most apparent in Middleman’s thoughtful analysis of Wilke’s contributions to the Hetero Is exhibition at the NYCATA (New York City Art Theatre Association) Gallery in 1966–67, which examines the way in which her sculpture stood apart from the predominantly figurative erotic art of her heterosexual male counterparts.

The fifth chapter provides an important consideration of the lesser-known artist Anita Steckel. Outside of Richard Meyer’s writing on Steckel, and an earlier essay published by Middleman, little scholarly literature exists on the artist’s work.6 This chapter therefore helps to frame Steckel’s contributions to feminist discourse on erotic art. Looking at her cheeky Mom Art series (1963) and her provocative Giant Women On New York (1969–74) and New York Skyline (1970–80; fig. 1) series, Middleman argues that Steckel’s sexually charged photo-based works “used montage to navigate a difficult territory in representation between the pleasure of eroticism and the critique of patriarchal power” (151). This “difficult territory” that she traversed often provoked controversy, particularly when she exhibited works depicting male genitalia. Similar to Meyer’s writing on Steckel, the chapter centers on the attempted censorship of Steckel’s Rockland Community College exhibition in 1972, in large part a response to her phallic imagery. During the controversy, Steckel initially downplayed the erotic content of the work in favor of stressing its broader attack on the oppressive forces of American phallocentric society. As Middleman states: “The threat of censorship set in motion a paradoxical operation, drawing attention to her sexual iconography while, at the same time, producing a language for defending the work that denied its erotic aspects” (150). This double bind led Steckel to establish the Fight Censorship Group (FCG) in order to find ways to discuss and promote work by women that openly explored sexual themes (Middleman examines the FCG in this chapter and her conclusion, which focuses more specifically on their group activities). Middleman shows how Steckel, in both her work and her organizing, proactively participated in the feminist art movement as a result of her consciousness-raising about erotic art, even if she has been subsequently ignored by art-historical narratives of the period.

Throughout Radical Eroticism, Middleman addresses the complex reasons for the omission of erotic art by women in histories of American art of the 1960s and recuperates moments of controversy and conflict provoked by these underconsidered female artists, such as Edelheit and Steckel, as well as more canonical feminist artists such as Schneeman. The ways in which issues of race, ethnicity, and nationality intersect with those of gender and sexuality are, however, rarely explored. Artists of color such as Marisol, Yayoi Kusama, and Yoko Ono are touched upon for the purpose of comparison yet are not examined in depth. Similarly, the New York–centered nature of Middleman’s study leaves lingering questions about the role of erotic art in the transformation of American art and sexual politics on the West Coast by artists such as Marjorie Cameron and Barbara T. Smith. And despite the stated focus on “women, art, and sex,” lesbian sexuality is only explored insofar as it serves as a paradigm in feminist art discourse that opposed heterosexuality. That said, the choice to concentrate on white, heterosexual female artists working in New York during the 1960s hones the narrative and reveals overlapping concerns regarding the sexual body in art in a highly influential social context. From chapter to chapter, we see how prominent New York critics and curators, such as Barbara Rose and Lucy Lippard, changed their interpretations of women’s erotic art over the course of the 1960s to increasingly merge formalist interests with feminist politics (101–3; 117; 127–32; 165–67).

The strength of Radical Eroticism lies in the depth of Middleman’s archival research, engagement with period sources, and close reading of key works and their reception. She provides an expertly researched and compellingly written narrative of the reorientation of the discourse on erotic art by heterosexual female artists over the course of the 1960s. Although her individual case studies often reinforce existing arguments about the structure and significance of these artists’ works (particularly in the chapters on better-known artists, such as Schneemann and Wilke), the book as a whole serves to recontextualize their practices in relation to feminist discourse on erotic art, thereby bringing to light the overlooked contributions of female artists to period debates about gender and sex in art. In the new feminist era of #MeToo, which at times appears in conflict with the legacies of sexual liberation, Radical Eroticism helps us to remember that women’s liberation and the sexual revolution have shared origins in the politics of the 1960s. Complexly intertwined, this discourse, as Middleman demonstrates, has much to offer when brought into dialogue instead of remaining polarized.

Cite this article: Miriam Kienle, review of Radical Eroticism: Women, Art, and Sex in the 1960s, by Rachel Middleman, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1695.

PDF: Kienle, review of Radical Eroticism

Notes

- Serious scholarly considerations of eroticism in art include: Theodore Robert Bowie and Cornelia V. Christenson, eds. Studies in Erotic Art (New York: Basic Books, 1970); Thomas B. Hess and Linda Nochlin, eds. Woman as Sex Object, Art News Annual, vol. 38 (New York: Newsweek Inc., 1972); Laura Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989); Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality (Abingdon, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2002); Alyce Mahon, Eroticism and Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Hans Maes and Jerrold Levinson, eds., Art and Pornography: Philosophical Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). ↵

- Serious scholarly considerations of eroticism in art include: Theodore Robert Bowie and Cornelia V. Christenson, eds. Studies in Erotic Art (New York: Basic Books, 1970); Thomas B. Hess and Linda Nochlin, eds. Woman as Sex Object, Art News Annual, vol. 38 (New York: Newsweek Inc., 1972); Laura Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989); Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality (Abingdon, UK: Taylor and Francis, 2002); Alyce Mahon, Eroticism and Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Hans Maes and Jerrold Levinson, eds., Art and Pornography: Philosophical Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). ↵

- Amelia Jones, Body Art/Performing the Subject (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998); Anette Kubitza, “Fluxus, Flirt. Feminist? Carolee Schneemann, Sexual Liberation and the Avant-Garde of the 1960s,“ n.paradoxa 15 (July/September 2001): 15–29. ↵

- Kalliopi Minioudaki, “Pop’s Ladies and Bad Girls: Axell, Boty and Drexler,“ Oxford Art Journal 30, no. 3 (2007): 402–30; Kalliopi Minioudaki, “Pop Proto-Feminisms: Beyond the Paradox of the Woman Pop Artist,“ Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958–1968, eds. Sid Sachs and Kalliopi Minioudai (New York: Abbeville, 2010), 90–141. ↵

- David Getsy, Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture and the Expanded Field of Gender (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), xii. ↵

- Richard Meyer, “Hard Targets: Males Bodies, Feminist Art, and the Force of Censorship in the 1970s,“ WACK: Art and the Feminist Revolution (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 262–83; Rachel Middleman, “Anita Steckel’s Feminist Montage: Merging Politics, Art and Life,” Woman’s Art Journal 34, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2013): 21–29. ↵

About the Author(s): Miriam Kienle is Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Kentucky