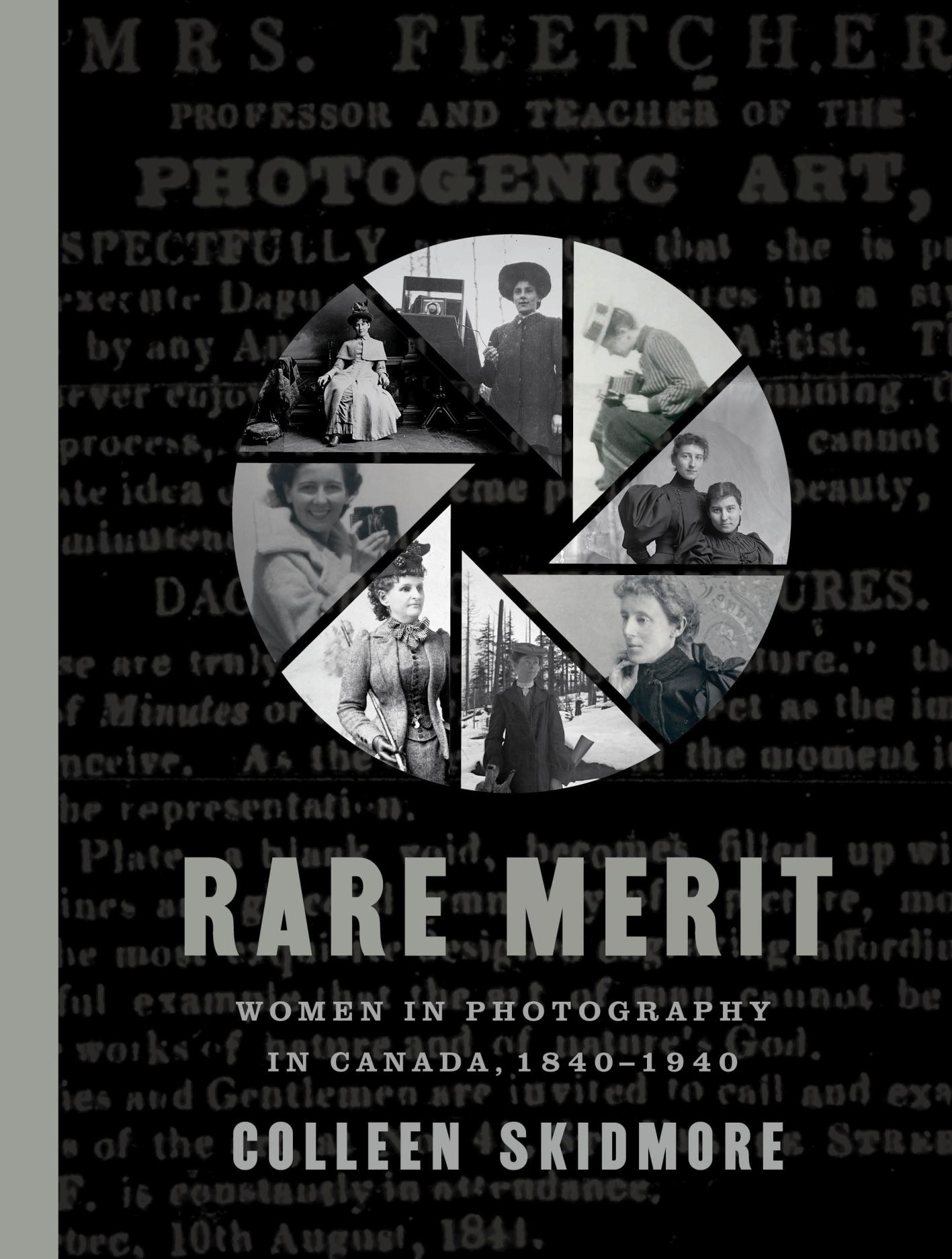

Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840–1940

PDF: Cavaliere, review of Rare Merit

Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840–1940

by Colleen Skidmore

Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2022. 368 pp.; 157 illus., 6 maps; appendices. Paperback: $39.95 CAD (ISBN: 9780774867054).

“Why women?” In the introduction to Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840–1940, Colleen Skidmore reflects on this question posed by the late American photography historian Naomi Rosenblum, known in photo history classrooms everywhere for her 1984 survey text, A World History of Photography, now in its fifth edition. This question reminds me of Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” which, like Rosenblum’s historical text, has been republished and revised many times over the last fifty years. Nochlin suggests that instead of falling prey to the question’s trap by offering up examples of “great” women artists from history or by conceiving of a different criterion of greatness for women artists all together, we should instead think about why such a question even requires asking in the first place. Nochlin urges her readers to consider the larger structures of inequity at play within the discipline that have marginalized women from achieving the institutional status of greatness. The question “Why women?” in art studies is not a new one, though Skidmore’s Rare Merit is evidence that it remains pressing.

Skidmore, a professor emerita at the University of Alberta, has dedicated her extensive and distinguished career to signaling and addressing the gendered gaps in Canadian photographic histories through her rich collection of published essays and in her two monographs, This Wild Spirit: Women in the Rocky Mountains of Canada (2006) and Searching for Mary Schäffer: Women Wilderness Photography (2017). In Rare Merit, Skidmore takes heed of Nochlin’s call to investigate the very structures and institutions that have shaped the histories of women in photography. Skidmore’s introduction describes the ways women have been blocked or marginalized from photographic pursuits, both commercial and creative; the ways that records of women photographers have been minimized in archival processes or left to disappear altogether; and the general lack of scholarship focused on women in photography. These ideas and conditions extend beyond the geographical and cultural bounds of Canada, where Skidmore centers her investigation, having resonance throughout photographic histories more broadly.

The breadth of Skidmore’s archival investigation is expansive, despite the fact that archival records are often scant. The richly illustrated book (with images both well-known and published here for the first time), the great number of women photographers discussed, and the range of archival findings (from news clippings to gelatin silver prints) are testaments to Skidmore’s range of investigation. To accommodate the scope of such a comprehensive study, one that Skidmore began in 1991, the chapters of the book take shape in various ways.

Chapter 1 is the only section devoted specifically to a single photographic form, the daguerreotype. It is also the place where Skidmore establishes the central premise of Rare Merit’s overall investigation: women photographers had a central and profound impact on the development of early photography. Here, Skidmore couples one of the earliest photographic forms, the daguerreotype, with the first-known advertisement for a commercial photographic practice by a woman. In an 1841 ad, Mrs. Fletcher promotes herself as a “professor and teacher of the photographic art” (15). Skidmore places this little-known figure into the annals of more established photographic history, specifically alongside Louis Daguerre and the medium’s invention. The author thus offers a radical reconsideration of early photography, one in which women photographers, like Fletcher, were responsible for familiarizing people with photography, ultimately leading to the new medium’s popularization, uptake, and success.

In chapter 2, Elise Livernois is positioned as central to the establishment, operation, and success of Livernois Studio in Quebec City, both during and beyond her lifetime, despite the fact that she faced restrictive social conventions and legal circumscriptions. Skidmore’s focus on Livernois illuminates what it was like to begin a photographic enterprise as a woman, while also situating her work within a broader understanding of photography’s contributions to nineteenth-century visual culture and its commodification therein. Skidmore’s investigation of the Notman Studio in Montreal in chapter 3 further examines the socioeconomic conditions and struggles of women behind, in front of, and around the camera, writing: “The women who worked in photography during the era of grand studios filled technical, artistic, and sales positions” (60). Skidmore provides new interpretive approaches to the data, both visual, in the form of portraits, and statistical, in the form of census and studio records.

Chapters 4 and 5 both signal new attitudes and uses of photography and photographic technologies in the studios of Hannah Maynard in British Columbia and Geraldine Moodie in Saskatchewan and Alberta, both proprietors of their own photographic enterprises. Of Moodie, Skidmore writes, “She differs from Hannah Maynard and other urban-based commercial photographers, whose work was integrated over decades in the social and cultural building of their locales. . . . By contrast, Moodie herself worked on the front lines of colonization, her subject matter and purpose determined and motivated as much by professional ambitions as by national aspirations and public interest” (141). In both chapters, Skidmore deals sensitively with photographs of Indigenous and colonized people as they appear in portraits. Her approach situates settler women as active participants in enacting colonial processes through their cameras. Skidmore makes note of how the history of women in photography intersects with questions and gaps in our knowledge of Indigenous and Black photographers in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century North America.

The last three chapters of Rare Merit are thematic, moving across a range of photographers and covering numerous stories drawn from archival records, which are more often than not incomplete due to deep-seated biases against viewing the work of women photographers as worthy of documentation. Because these chapters, unlike the previous ones, do not trace the story of an individual photographer or studio, the rhythm of the text changes from narrative to overview. These chapters also provide an open invitation to scholars to take up their own further investigations about the figures presented. While these women have received less scholarly attention and feature less prominently in the archives, they are no less extraordinary in their contribution to the medium and its history.

The themes of each of the remaining chapters are ones that are introduced in some capacity in the more biographical preceding chapters. For example, in chapter 6 on travel photography and photojournalism, Skidmore remarks of Annie Brassy that, like Moodie, she “played two public roles: she was the wife of a public figure who was employed by a national institution, but she was also a photographer and writer of empire in her own right” (145). Chapter 7, on commercial studio photographers, describes how, in pursuing independent employment, women photographers “pressed against the boundary of women’s social place, and the field [of studio photography] itself” (191). Of particular interest here are Skidmore’s accounts of Éugénie Gagné, Rosetta Carr, and Elsie Holloway. Chapter 8 discusses camera clubs and amateur associations that sought to move the medium toward art. There is also a discussion of the photo albums that were composed and collected by women across Canada. These were produced under various circumstances, including professional settings, such as those by Mattie Gunterman in the mining camps of British Columbia, as well as for private use, such as the snapshots of author Lucy Maud Montgomery in Prince Edward Island.

Rare Merit presents both history and historiography framed through rigorous archival work and deep scholarly research. Skidmore deftly compares Canadian women photographers with their better-known counterparts, such as Gertrude Käsebier, Edith Watson, Margaret Bourke-White, or Margaret Watkins, whose work sometimes intersected with Canadian contexts. Rare Merit could and should find a place in university classrooms as both an introduction to the history of photography and a methodological exemplar for conducting photographic research. Skidmore also thoughtfully dovetails lesser- and better-known scholarly histories of photography. For example, she compares the practices and photographs of the Gushul Studio in Alberta and its leadership by a woman with those by Leslie Shedden from Nova Scotia, which photography historian Allan Sekula examined in his widely known 1983 essay “Photography between Labour and Capital.”

The word “rare” is used frequently throughout the text, but what it signals, perhaps ironically, is that merit was not rare at all. Rather, photographic history, Canadian and beyond, is replete with extraordinary women photographers. In fact, Skidmore points to a great many firsts for women in photography, such as the first woman to open a studio in a particular geographic area. But what the study reveals is that the knowledge and record around women in photography has been so circumscribed that there might also be the exciting possibility that these firsts are not firsts at all. She ends with her own answer to “why women?,” writing, “Women photographers and studio workers have been present and active from the beginning. In this book, I have concentrated on just one country—one small corner of the world. If women photographers around the globe were brought into the light, if the sweep of their work internationally were discussed, imagine how radically our understanding of the history photography would change” (280). Rare Merit shows us that there may be countless stories of women in photography waiting to be uncovered and studied, whose records may not have survived in archival and private collections but whose impact on the very history of photography is of outstanding merit.

Cite this article: Elizabeth Anne Cavaliere, review of Rare Merit: Women in Photography in Canada, 1840–1940, by Colleen Skidmore, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17497.

About the Author(s): Elizabeth Anne Cavaliere is an instructor at Ontario College of Art and Design University in Toronto, Canada.