Reflecting on “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History”

Editors’ Note: This article and the responses to it comprise the final “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History” project generously funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Click on the Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History tag for all projects in the series.

Contributors

Albert-László Barabási and Louis Shekhtman, “Who Supports American Art Museums? Introducing a New Dataset and Data Sources about Museum Funding”

Adam Levine, “A Response to Barabási and Shekhtman”

Terence Washington. “Who Funds American Art? Everyone Does.”

Jeffrey Abt, “The Nature and Sources of American Art Museum Funding”

Nizan Shaked, “Against the Private Museum”

What is an inclusive digital art history? This is a question that I asked myself when I was appointed Panorama’s Digital Art History Editor in 2019 and asked to lead the generous Terra Foundation–funded multiyear initiative “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History.” The grant was designed to work toward making digital art history inclusive in a range of ways: through free talks to the public (a wonderful lecture and panel), a workshop for early-career scholars who were interested in engaging with methods but lacked the resources at their home institutions to do so, and the publication of a range of digital art history articles in Panorama.

Throughout this process, I have come to understand that there is not a single answer to what makes digital art history inclusive or exclusive. It can be made inclusive by demonstrating that simple, accessible quantitative methods deliver outsized scholarly insights in art history. It is inclusive by deploying these same methods to recapture and tell the stories of artists traditionally marginalized or overlooked by art history. Finally, it can be inclusive by fostering interdisciplinary scholarship and conversation. This last point is the focus of this special section. Designed to echo Panorama’s signature Colloquium, it presents a core essay and four responses to that essay. However, before introducing this section in more detail—which, fitting for the end of grant, examines sources of funding in American art—it is useful to briefly recap some of the initiative’s earlier efforts to make digital art history more inclusive.

A primary focus over the initial two years of the grant was to provide support to art historians who had research projects ripe for quantitative study but who, without the help of the Panorama team, did not necessarily have the technical resources and capabilities to turn their carefully crafted lists of information into fodder for compelling scholarly articles. First, alongside Project Manager Johnathan Hardy, the Panorama editorial team worked with workshop participants both one-on-one and in a group to teach them the methods necessary for writing an effective digital art history article. This included technical skills like how to set up spreadsheets and use mapping software, but it also included learning how to build a dataset and formulate a hypothesis that can be tested—or at least explored—with the data you have.

Two feature articles were published after this workshop. We encouraged authors to create relatively simple maps and graphs using a combination of Excel and ArcGIS. The two articles—“Commemoration of an Epoch: Monuments to the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States” by Sierra Rooney and “From Center to Periphery: The Lifespan of New York City’s Tenth Street Studio Building and the Canon of American Art” by Mary Okin with Celie Michard—demonstrate that digital art history does not need to be enormously technical to be valuable to the field. In showing the power of relative simplicity and explicitly providing opportunities to scholars without digital humanities labs or other similar resources on campus, Panorama was able to make the practice of digital art history more inclusive. Beyond the practical questions, these articles helped excavate information about artists who have historically been excluded from American art scholarship. Therefore, the project was also inclusive in its focus on previously neglected or marginalized figures in art history.

These dual messages about the power of digital art history to tell overlooked stories while using comparatively simple technologies carried through to our two virtual, free, and very well-attended public events. The first was a 2021 keynote lecture by Paul Jaskot (Professor of Art, Art History and Visual Studies, Duke University). The second was a panel featuring Dana E. Byrd (Assistant Professor of Art History, Bowdoin College), Farès El-Dahdah (Professor of Art History, Rice University), and Brianna Heggeseth (Associate Professor of Statistics, Macalester College).

For this final installment of the “Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History” initiative, we are trying a different approach and testing how digital methods can be inclusive by bringing art history into conversation with other fields—particularly more quantitative fields. Speaking a shared language of data, maps, and graphs, art historians can potentially collaborate with economic historians, quantitative sociologists, data scientists, and other scholars from data-driven fields. In the other direction, as art history demonstrates its openness to quantitative approaches, it may attract the attention of scholars in these fields who bring a new methodological eye to art-historical research problems. Interdisciplinarity is, I believe, a form of inclusion. Panorama gestured in this direction by inviting Professor Heggeseth, a statistician who has partnered with museums and art historians, to participate in the public panel. This special section fully test-drives that concept.

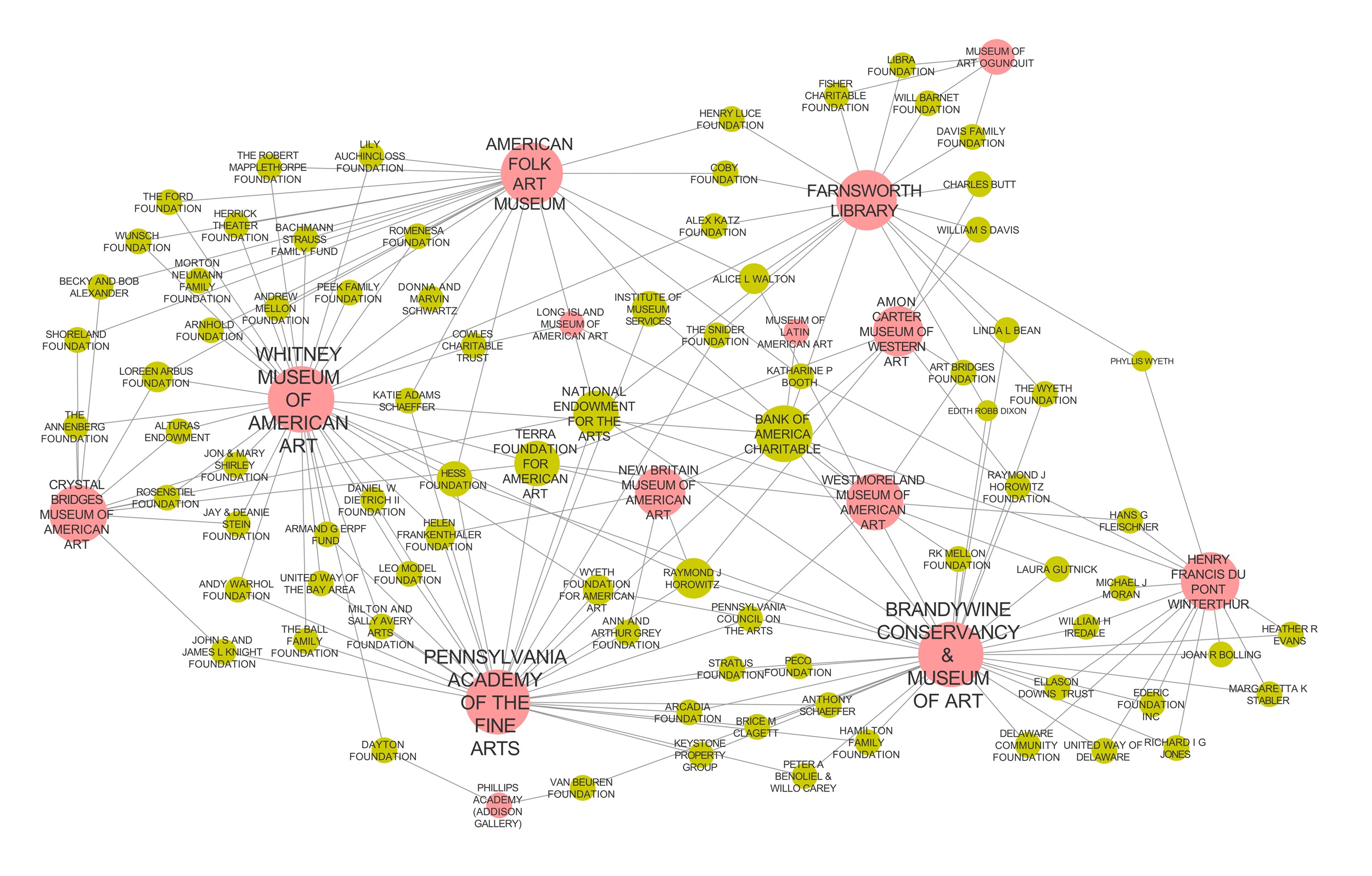

The central feature of this section is a short article by two data scientists, Albert-László Barabási and Louis Shekhtman, who have created a massive dataset of tax information about the funding of museums in the United States (fig. 1). For Panorama they have focused their analyses on museums with a mission related to American art. We have invited four scholars—all trained art historians—to respond to Barabási and Shekhtman’s article. One, Adam Levine from the Toledo Museum of Art, is a museum director. Another, Terence Washington, is a writer, critic, and veteran of museum work. The remaining two—Jeffrey Abt and Nizan Shaked—are both professors. Each author has their own positive and negative views of Barabási and Shekhtman’s article. Considered together, these essays and the conversation they represent are another form of an inclusive digital art history where the discipline opens itself to scholars from other fields and then has a healthy debate about what we can and cannot learn from their contributions. It is a fitting capstone to a Terra-funded initiative that asked us to define inclusion broadly.

Cite this article: Diana Seave Greenwald, introduction to “Reflecting on ‘Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History,’” special section, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18316.

About the Author(s): Diana Seave Greenwald is the William and Lia Poorvu Curator of the Collection at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.