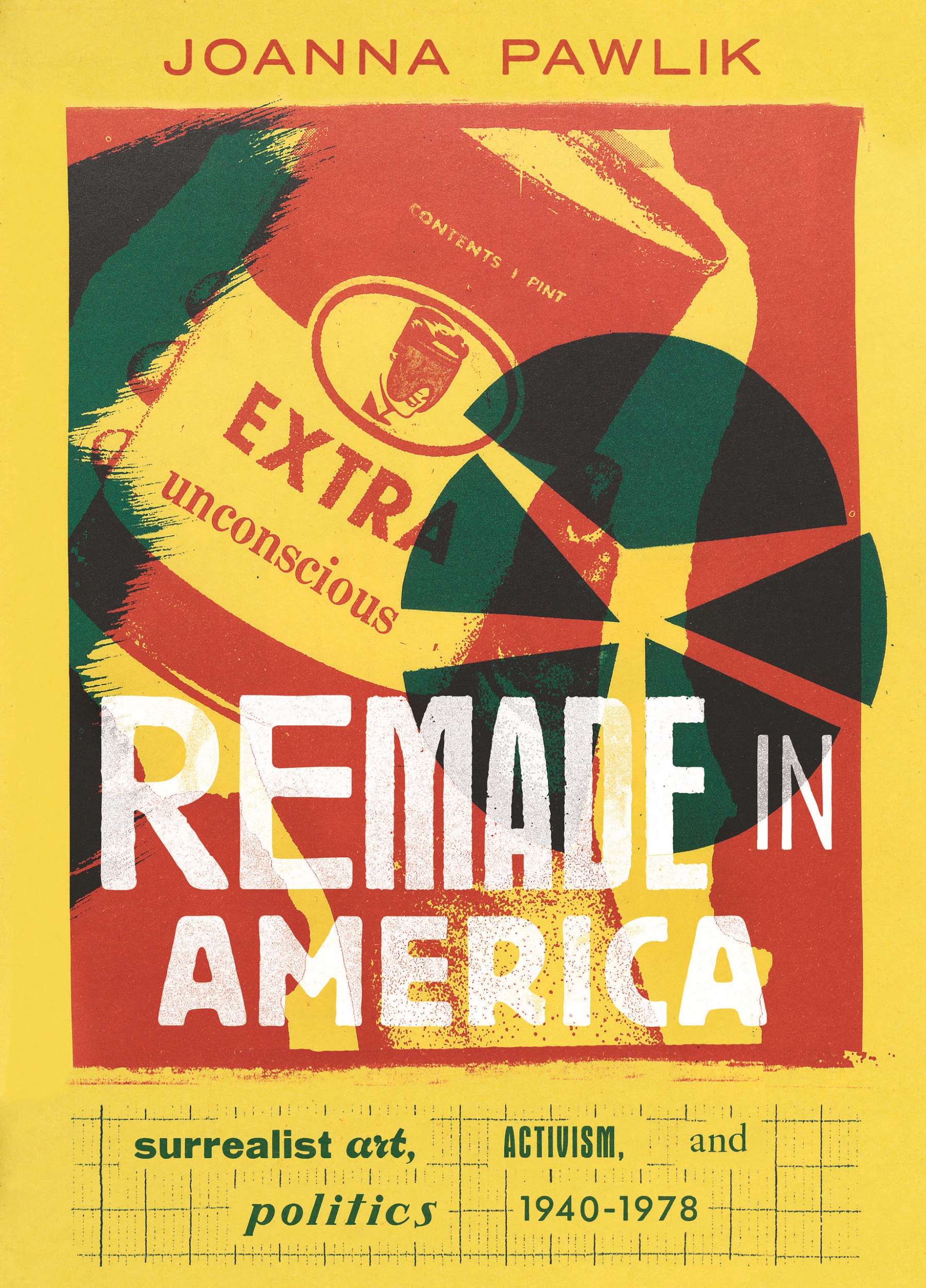

Remade in America: Surrealist Art, Activism and Politics, 1940–1978

By Joanna Pawlik

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021. 296 pp.; 48 color illus.; 55 b/w illus. Hardcover: $65.00 (ISBN: 9780520309043)

Joanna Pawlik’s book Remade in America is part of a turn in scholarship that examines Surrealism’s reverberations transculturally and transcontinentally to reposition Surrealism “against the grain” of its European, heteronormative, and white origins.1 Pawlik throws into high relief Surrealism’s decolonial, antiracist, antiwar principles, “remaking” the movement around its more activist practices.

Pawlik is particularly focused on considering Surrealism’s practitioners in the United States, where, she persuasively argues, “Surrealism’s minoritarian status rendered it of particular significance to those who were negotiating other forms of difference, whether national, ethnic, sexual or gender” (2). Though Surrealism in its many forms was pervasive during much of the period of Pawlik’s study (1940–78), it remained “minoritarian” because it was consciously excluded from the prevailing histories that were actively being written to buttress formalist art practice. Surrealism’s messy blend of abstraction and figuration across many mediums presented a problem for critics trying to consolidate a modern style, as did the contradiction of the movement’s political convictions and its rampant commercialism. During the immediate postwar moment, when defining “American” art seemed urgent, Surrealism’s insistence on irrationality, its foreign origins, and its interest in the quotidian were all elements to be overcome. This context might explain the paradox of how so many disparate artists in the United States became attracted to Surrealism’s premises—they had found something that was, on the one hand, circulating fluidly in American culture and, on the other hand, dismissed or even derided by influential gatekeepers. Pawlik argues that this lack of endorsement in the United States forced Surrealism to the fringe, where it derived more power in being decentered and diffuse.

As she elucidates this radical fringe, Pawlik hews closely to the notion of influence. While she expands the purview of Surrealism to include queer writers, Black artists, and political activists, the protagonists of Pawlik’s case studies were all, at some point, directly in contact with the original French group. Pawlik acknowledges that André Breton’s own understanding of Surrealism foreclosed many of the interventions described in her book, and yet he haunts each encounter, even as the practitioners he inspired disrupted Surrealist doctrine.

In the first chapter, “Re-Viewing Surrealism: Charles Henri Ford’s Poem Posters (1964–65),” Pawlik situates Ford’s work as a useful bridge from other accounts of Surrealism’s presence in the United States. Going beyond the well-known period of View magazine and Ford’s work with the Surrealists in exile, Pawlik focuses on Ford’s campy collage work of the 1960s, positioning him as a queer interlocuter. In the second chapter, “Encountering Surrealism: Nadja (1928) and Autobiographical Beat Writing,” Pawlik considers how Breton’s book Nadja (translated into English in 1960) fascinated a younger cohort of burgeoning American writers, especially those of the Beat generation, who took Breton’s nonlinear account of convulsive love and sought to complicate its “masculinist, heteronormative, Caucasian erotics” in new ways. In the following chapter, “Blackening Surrealism: Ted Joans’ Ethnographic Surrealist Historiography,” Pawlik considers how Surrealist ideas offered Joans a way to counter racist culture in the United States. Chapter 4, “Turning on Surrealism: Queer Psychedelia,” locates Surrealism in California; it analyzes the queer psychedelia of Marie Wilson but also includes a section on Brion Gysin’s Dream Machine (1961), which debuted in Paris. Pawlik’s final chapter, “Hystericizing Surrealism: The Marvelous in Popular Culture,” moves to the Midwest, looking especially at the political activism of the first “official” group of US Surrealists in Chicago, their fascination with American comics, and the 1978 exhibition titled the 100th Anniversary of Hysteria.

Although Pawlik’s account nominally ends in 1978, the book usefully moves around in time and place. Pawlik challenges previous chronologies of Surrealism by tracing artists’ careers beyond the 1970s (and into the 1990s, in some cases). She also reflects on the artists’ formative years, when some figures engaged with Surrealist ideas long before coming into contact with Breton while others expanded on the movement’s possibilities long after any official involvement. Surrealism, unlike other movements of the so-called historical avant-garde, defies the logic of a this-begat-that lineage, and Pawlik’s case studies similarly buck this kind of structure. Likewise, Pawlik also plays with place, following artists who traveled back and forth to Europe and those whose work moved across the Atlantic. It is refreshing to see the United States represented not only by New York but by a variety of cities across the country as part of a larger expression of the dynamics of the Surrealist network, which exceeded the bounds of any particular geography or temporality.

Pawlik especially highlights how Surrealism’s often-downplayed leftist politics continued to be meaningful to younger generations in the United States during the period of her study. One of the best examples of this political engagement is found in her writing on Joans, who activated Surrealism’s anticolonial, antiracist potential. Joans wrote a letter of introduction to Breton, which was published as “Ted Joans Speaks” in 1963 in the French Surrealist periodical La Breche. In the letter, Joans glossed Breton’s opening text in Nadja but quickly moved beyond: “Qui suis-je? . . . I am an Afro-American and my name is Ted Joans. . . . Without surrealism I would have been incapable of surviving the abject vicissitudes and racial violence which the white man in America imposed upon me every day. Surrealism became the weapon I used to defend myself” (74). That Joans found in Surrealism a useful strategy to subvert American sociopolitical realities is compelling in itself; Pawlik’s discussion of his oeuvre makes it more so. Yet Pawlik also repeats an anecdote about Joans bumping into Breton “by chance, at a bus stop”—a textbook surreal encounter if ever there was one (121). Auspicious as it may be, we are left wondering about the role of Surrealist mythmaking in Joans’s own self-fashioning, something, it seems, in which he reveled and through which he sought recognition.

Throughout her account, Pawlik emphasizes the interventions her subjects made into Surrealist historiography. Yet, because she assiduously avoids discussion of the museums, galleries, and critics that were working during this period to historicize Surrealism, we do not get a full sense of how these American artists engaged with the institutions that were actively framing Surrealism’s legacy. For example, the landmark exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage (1968), is only briefly mentioned in the introduction, though it became a touchstone for reassessing Surrealism’s still-relevant role in American aesthetics and politics, especially as artists and activists protested the very premise of institutionalizing Surrealism in museums.

William Rubin, the curator of Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage, assembled a primarily historical show in 1968 in part because he had become convinced that outside of pure abstraction, nearly everything being produced by contemporary artists was in some way related to Surrealism.2 It is interesting to consider his contemporaneous assessment of the capaciousness of the Surrealist spirit alongside Pawlik’s study of very specific mobilizations of Surrealist ideology in the United States. The artists illuminated in Pawlik’s book were not included in Rubin’s exhibition, likely because they embodied Surrealism as radical activism, a living force. Rubin was trying to assimilate Surrealism into a canon of formalist aesthetics, far from the political, poetic realm Pawlik seeks to recover. To demonstrate that Surrealism was more than just a hazy memory for postwar artists, Pawlik limits herself to those for whom Surrealist tenets remain a central node, but she applies a feminist and queer approach that skillfully illuminates Surrealism’s evolving vitality. Remade in America reveals what the protesters at the 1968 MoMA exhibition knew well—that Surrealism’s potency lay in its ability to evolve, in its very refusal to be history, giving shape to a far more multidimensional picture of the diversity of American art.

Cite this article: Sandra Zalman, review of Remade in America: Surrealist Art, Activism and Politics, 1940–1978 by Joanna Pawlik, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13337.

PDF: Zalman, review of Remade in America

Notes

- Other recent examples include Elliott King and Abigail Susik, eds., Radical Dreams: Surrealism, Counterculture, Resistance (University Park: Pennsylvania State Press, 2022); Stephanie d’Allesandro and Matthew Gale, eds., Surrealism Beyond Borders (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021); Natalya Lusty, ed., Surrealism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021); Ingrid Pfeiffer, ed., Fantastic Women: Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo (Munich: Hirmer, 2020); Jelena Stojković, Surrealism and Photography in 1930s Japan: The Impossible Avant-Garde (London: Bloomsbury, 2020); Penelope Rosemont, Surrealism: Inside the Magnetic Fields (San Francisco: City Lights, 2019); Nicholas Hall, ed., Endless Enigma: Eight Centuries of Fantastic Art (New York: David Zwirner, 2019). ↵

- Harold Rosenberg goes even further, including “the ‘pure’ art of geometrical forms” within Dada and Surrealism’s legacy and writing that “all advanced art of our time carries in it some mark of Dada-Surrealist influence”; “MoMA Dada,” New Yorker, May 10, 1968, 140. ↵

About the Author(s): Sandra Zalman is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Houston.