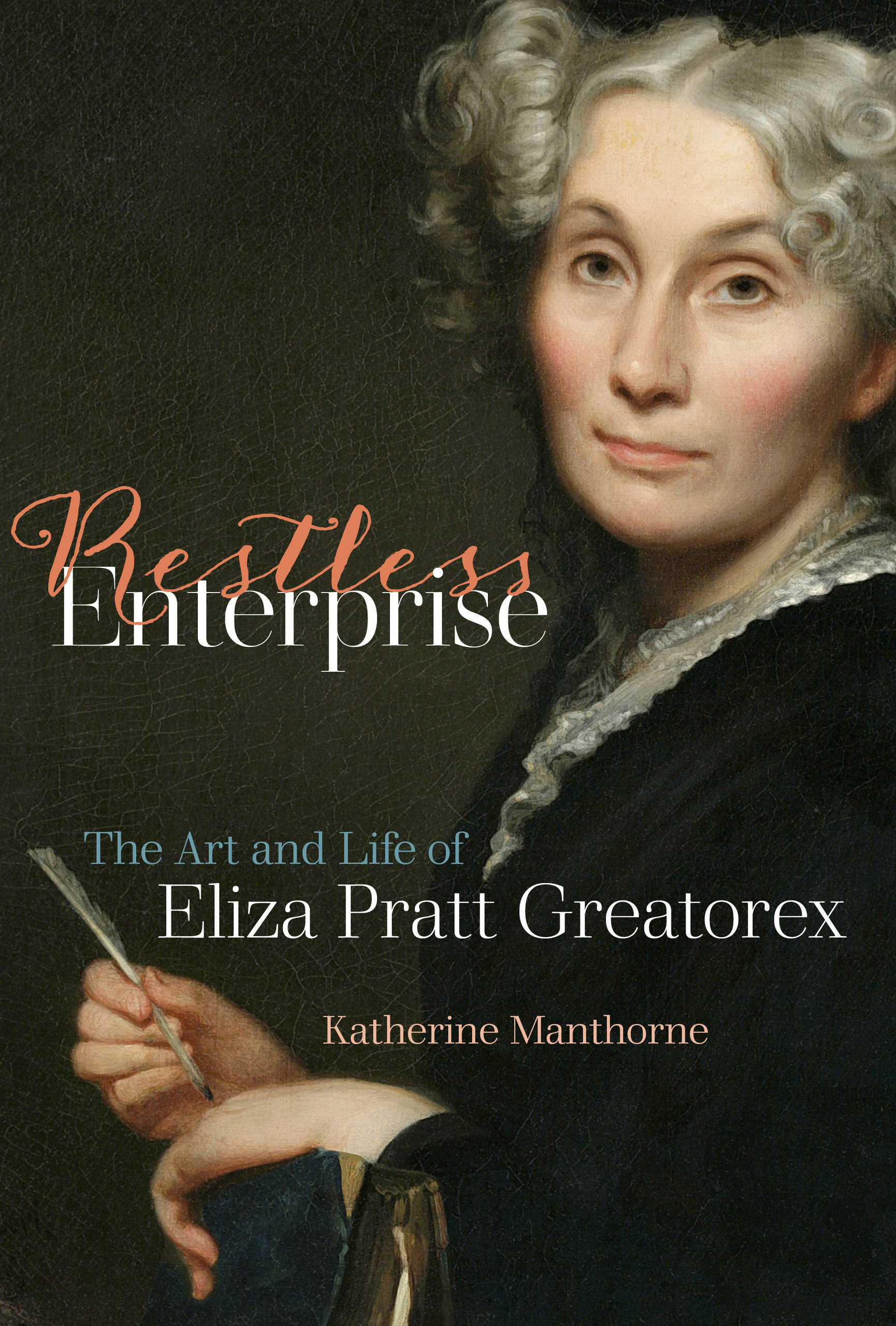

Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex

by Katherine Manthorne

by Katherine Manthorne

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2020. 352 pp.; 36 color illus.; 44 b/w illus.; Hardcover: $34.95 (ISBN: 9780520355507)

This long-awaited study of artist Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819–1897) effectively interweaves her life narrative and the larger art-historical picture of her times, illuminating that historical context and restoring a once well-known American artist to her place in history. And what a history it is—her career spans the years from the late 1850s to the early 1890s—decades of social, economic, and artistic change. Composed of a prologue, nine chapters, and an epilogue about the later careers of her daughters, the book, which is the product of twenty years of meticulous research, provides a wealth of detailed information, invaluable for any investigator of women in the visual arts or of the period. Greatorex, born in Ireland, was the anchor for a family of artists, especially her sister and her daughters, Kathleen and Eleanor. Eventually settling in New York City, she also traveled, with her daughters, to Colorado and to Europe, sometimes staying away from New York for more than a year at a stretch. The life of this artist, as author Katherine Manthorne posits, shows that the fifteen years between the end of the Civil War and the Centennial constitute a distinct era in American art history. This becomes quite clear when viewed from the perspective of women artists; American society and institutions were in flux, and women quickly stepped into the new niches created by modernization and those vacated by war. Manthorne connects Greatorex’s activities as an artist to many other elements of the history of art in nineteenth-century America: notable examples include landscape painting, the etching revival, book illustration, travel literature, and the institutionalization of art in the United States. This illuminating text also positions Greatorex within the history of American art, as well as the international art scene created by Americans traveling back and forth to Europe. She left few documents in her own hand, requiring any account of her life to work from the outside in; Manthorne makes a virtue of this necessity, mapping in multiple ways the artist’s life and artistic production.

The book opens with a prologue narrating the demolition of New York’s St. George’s Chapel in 1868 and Greatorex’s documentation of this historic building. This brief section elegantly introduces the themes of change and memory that continue throughout the book as well as Greatorex’s commitment to drawing as an artistic practice. The first chapter starts with the artist’s natal family and the journey from Ireland to the United States. Born to an itinerant preacher and his wife, Greatorex moved fifteen times in the first twenty-two years of her life, presaging the mobility of her later years. Greatorex’s migration to New York City in 1848 brings one of the main narratives of the book sharply into focus: the restlessness that shaped Greatorex’s life and that is featured in the book title. Manthorne announces the stakes of recovering Greatorex’s life by briefly drawing parallels between Greatorex and three of her contemporaries—Herman Melville and Walt Whitman and their engagement with urban life, and Martin Johnson Heade’s peripatetic career—to remind the reader that the pattern of Greatorex’s life was shared by other artists and writers.

The year 1848 also saw the birth of the American suffrage movement and the growing number of women determined to make their own way in life. For Greatorex, making her own way meant making art; the second chapter, “Art, Domesticity, and Enterprise, 1850–1861,” documents Greatorex’s early career as a landscape artist and the renown she enjoyed. This chapter builds on earlier research showing that Greatorex and other women artists regularly engaged in plein-air painting, and that it was not just the men of the Hudson River School who have been canonized in the narratives of nineteenth-century American art.1 It also treats her 1849 marriage to Henry Wellington Greatorex, a musician and composer; in this period, she had three children, took on the task of raising her stepson, and became a widow with little money in 1859. The chapter sets the artist’s deepening investment in her career alongside the careers of her friend Emily Osborne and painter Lilly Martin Spencer. Greatorex’s trajectory as a painter of landscapes is here usefully compared not just to other artists but also to women nature writers, including Susan Fenimore Cooper. The elucidation of these artistic and literary networks, especially those between women, in which Greatorex played a key role, makes the book valuable to an audience broader than art historians alone.

The Draft Riots of 1863 and the accelerated modernization of New York City in subsequent years brought rapid changes to the built environment. The destruction of these buildings prompted Greatorex to add expressive ink drawings to her regular practice as she recorded the impact of the Civil War on her adopted home and its historic architecture. In chapter three, “Civil War and Architectural Destruction,” Manthorne convincingly positions these as commentary on the war, parallel to similarly oblique efforts by Heade, Fitz Henry Lane, and other artists of the period. She reads Greatorex’s images of buildings, often damaged or slated for destruction, as metaphors for war and the violent history of New York; Manthorne further postulates that the artist’s emphasis on domestic architecture or buildings, such as hospitals, specifically speaks to women’s experiences of the Civil War.

The next five chapters focus on Greatorex’s prime years, the 1860s through the 1880s, the final leg of what Charlotte Striefer Rubenstein dubbed “The Golden Age” for women artists in the nineteenth century.2 In chapter four, “Success in the New York Art World, 1865–1870,” the book’s panoramic view of Greatorex’s context shines. Her studio, located in a building full of up-and-coming artists, provided her with a community of colleagues, art instruction for her daughters, and a venue for her first forays into etching. This wide view includes Greatorex’s participation in social, literary, and artistic networks, often run by women; the publication of her first portfolio of drawings (Relics of Manhattan); exhibitions of her work at William Schaus’s prominent gallery; and her election as an associate member of the National Academy of Design in 1869—the second woman to achieve this honor—fourteen years after her work first graced its walls. “In the Footsteps of Dürer,” the next chapter, continues Manthorne’s finely grained account by turning to one of the artist’s many sojourns in Europe, particularly her trip to Germany to pursue her fascination with Albrecht Dürer, one she shared with many other artists on both sides of the Atlantic. Drawing all the while, in 1872, she published some of her drawings of Oberammergau alongside excerpts of her diary entries from her visit there. Upon returning to the United States, the subject of chapter six, “Taming the West: Summer Etchings in Colorado (1873),” the artist’s peripatetic journeys with her daughters included a sojourn in Colorado; at the time, this was an unusual undertaking for women unaccompanied by a man. But this chapter also reveals that Greatorex’s artistic network extended far to the West; on the outbound journey, she and her daughters visited Martha Reed Mitchell, friend of the artist and a collector and patron of some note.3 This chapter maps the work of Greatorex and her daughters against other contemporaneous western expeditions, the increasing importance of works on paper in American art, and women settlers in the West.

Old New York, the book produced from Greatorex’s drawings of New York, a ten-year project started in 1863, and arguably the most important undertaking of her career, is the subject of chapter eight. This ambitious undertaking cemented Greatorex’s position as a leading artist. It was issued in installments over the course of 1875, with more than eighty drawings and text written by her sister and collaborator, Matilda Despard. Manthorne sets this chronicle of urban transformation within the context of contemporary urban historians, other artists depicting the rapidly vanishing city landmarks, and the business of art. “Centennial Women, 1876–1878” treats the celebration of the Centennial, in which many women artists exhibited; Greatorex showed work in both the Women’s Pavilion and in the official art exhibition at the Centennial. Her daughter, Kathleen, penned several articles about women artists for The New Century for Women, extending the feminist ambitions of women artists and designers and the mission of the Women’s Pavilion itself. Eliza Greatorex and Susan B. Anthony were friends, and a feature of this chapter is the useful discussion of the women’s movements as manifested in the art world, especially for entrepreneurial women such as Greatorex.

The last chapter treats the impact of the economic troubles of the 1870s, which forced the artist to sell off the contents of her studio, her art collection, and her own work; she and her daughters then decamped for Paris and further adventures on the continent. There, Greatorex adopted etching as a major medium, one well-suited to her drawing skills. This chapter chronicles her early participation in the etching revival, setting it against the backdrop of the many women flocking to European studios seeking art instruction as well as the etching revival itself.4 Greatorex and her daughters continued their peripatetic pattern through the 1880s; she died in 1897 after a long illness, and so few records of her life in the 1890s have surfaced that this last period is “something of a blank” (271). The book closes with an epilogue about her daughters; Greatorex’s enterprise, while dependent on the labor of her daughter/apprentices, also launched their careers.

One of the best things about this book is that, in spite of its multitextured account of the artist’s life and work, the reader wants to know more about women artists in this period. Therefore, the book will likely serve to spur further scholarship on Greatorex’s daughters and other women in the art world of the period. Finally, the author’s clear and accessible prose helps the reader digest the multifaceted view that emerges from the book. This reviewer has one complaint: the illustrations are small, and for an artist for whom expressive details are an important part of their art, this is a disappointment to the reader. Many could have been produced as full-page images; the fact that they were not likely testifies to the difficulties (and expense) of art history publishing. Fortunately, some of Greatorex’s works are available via the websites of collections that hold them: the Ronald Berg Collection, Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, and the Brooklyn Museum.5 Not all of Greatorex’s works have been digitized by the latter institutions; one hopes that the publication of this book will soon prompt them to do so.

Cite this article: Andrea Pappas, review of Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex, by Katherine Manthorne, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11835.

PDF: Pappas, review of Restless Enterprise

Notes

- See, for example, Nancy Siegel and Jennifer Krieger, Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School, exh. cat. (Catskill, NY: Thomas Cole National Historic Site, 2010). ↵

- Charlotte Streifer Rubenstein, American Women Artists: From Early Indian Times to the Present (New York: Avon Books in association with G. K. Hall, 1982). ↵

- Katherine Manthorne, “Labor Pains: Women, Collecting, and the Birth of the American Art World, ca. 1876,” in Power Underestimated: American Women Art Collectors, ed. Inge Reist and Rosella Mamoli Zorzi (Venice, Italy: Marsilio Editori, 2011), 39–56. ↵

- Kristin Swinth, Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). ↵

- For the Berg collection, see https://www.ronaldbergcollection.com/pdf/greatorex.pdf. Simple searches of the collection databases of the New York Public Library (https://www.nypl.org/), Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/collections/), and the Brooklyn Museum (https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/) yield works by Greatorex. ↵

About the Author(s): Andrea Pappas is Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Art History, Santa Clara University