Sam Middleton: Freedom’s Song

Born in Harlem, New York, in 1927, artist Sam Middleton forged a successful professional career abroad, largely in the Netherlands, where he resided from 1962 to 2015.1 At the time of his death on July 19, 2015, his 1960 collage painting, Out Chorus, was on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in America Is Hard to See, the inaugural exhibition for the new Manhattan location of the museum in the Meatpacking District. Acquired by the museum through a gift in the form of a purchase award from the Ford Foundation, it is the only Middleton in the Whitney’s collection. Team-curated and installed throughout the galleries, America Is Hard to See presented artwork from the permanent collection, including many that had been rarely on view “alongside beloved icons” to “unsettle assumptions about the American art canon.”2

Middleton often referred to his work as “an improvised solo,” and the presence of his singular (for example, only and outstanding) Out Chorus in the celebratory 2015 Whitney Museum exhibition is ironic and bittersweet. It perhaps sums up the relationship the artist had with America and that which mainstream American museums had with his oeuvre: hard to see. Out Chorus was made in Madrid, where it was first exhibited before being shown in New York City at the gallery Contemporary Arts (fig. 1).3 In America Is Hard to See, it appeared on the sixth floor in the thematic section “Scotch Tape” (named after Jack Smith’s 1959–62 film), with artwork that displayed “extensive use of nontraditional materials, often scavenged in junk shops and along city streets.”4 For Middleton, who used Elmer’s Glue, collage was quintessentially and formatively European, and his own collage paintings are expressions of the internationalist, indeed democratic, imprint he achieved by leaving the United States. As he wrote, “the artist is, like a human mirror, reflecting ideas, images, feelings and the impressions of his environment as he sees and feels them. In this sense collage is a chain of connecting ideas and expressions like fragments of that broken mirror, gathered and mended.”5 Developing his artistry while living abroad, Middleton would position his work in prevailing canonical artistic traditions of twentieth-century European modernism, particularly the innovation and creative experimentation inherent to collage.

In 1944 Middleton signed on with the Merchant Marine to see the world beyond Harlem. For the next ten years, his voyages took him to several continents, where he reveled in the local theater, music, and museums. Between voyages, New York City was his base. In the 1950s, he rented a loft in Greenwich Village, a haven for artists and a hub for the Beat Generation. His social circle included a small group of black artists whom he would later befriend in Europe—Walter Williams, Clifford Jackson, Harvey Cropper, and Herb Gentry—as well as painters Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell. Their haunts included the Cedar Tavern and the Five Spot, a jazz club. In the Village, he met musicians Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and John Coltrane.6 Motherwell and Middleton conversed mostly about poetry; Kline encouraged Middleton’s fellowship application to the John Hay Whitney Foundation and advised him to seek his artistic success outside New York, beyond the market constraints of racial discrimination. As a black artist in New York, Middleton felt powerless.7

Middleton used the terms autodidact (in Dutch) and “self-taught” to describe his artistic education. His love of sketching emerged while he was studying to be a tailor in high school. “[M]y head and heart turned seriously towards painting around 1947–1948. My first important break was my first scholarship award by Instituto Allende in Mexico, 1956.”8 Painting in oil at that time, he used primarily figural subject matter. Middleton’s scholarship for one year of study at the Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende was influential indeed—not for the classes, which he ceased attending, but for the environs, artistic friendships, and opportunity to focus full time on his art.9 In Mexico in 1957, Middleton began working with collage, scavenging plastered poster paper advertising bullfights, and it became over time more than a signature medium.10

While Middleton sought his creative freedom outside the United States, his work continued to be recognized at home. Under the leadership of Emily A. Francis, Contemporary Arts sponsored Middleton’s first solo exhibition in New York in October 1958. A second solo exhibition in 1960, reviewed by Stuart Preston for the New York Times, succinctly marked the artist as “a maker of collage.”11 This exhibition overlapped with the Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition Young America 1960: Thirty American Painters Under Thirty-Six, which included four of Middleton’s works from 1958 and 1959, on loan from Contemporary Arts.12 Middleton received word of their selection while in Madrid, where he was nearing completion of his John Hay Whitney Opportunity Fellowship.13 Like Out Chorus, the early collages were densely structured compositions of recycled, print-laden materials with muted earth tones. Artistic influences for him at this time include the Italian artists Alberto Burri and Afro (Libio Basaldella). As he observed, “[Afro] taught me a lot about shape and form, a sense of structure. Burri, too.”14

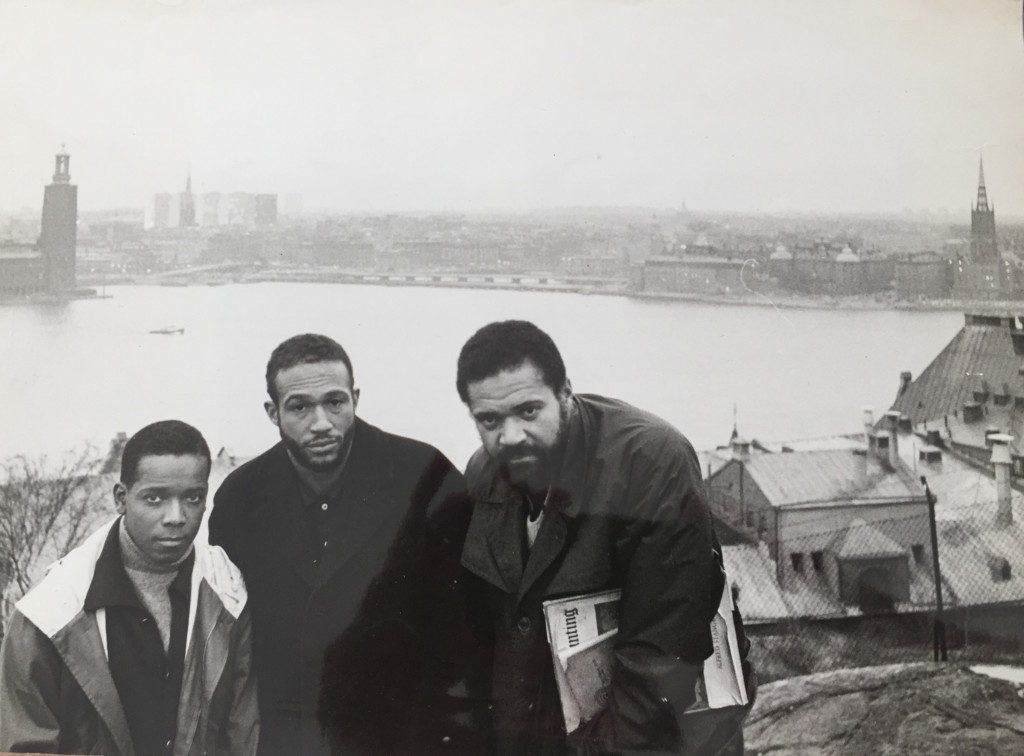

Many black artists, including musicians, writers, and dancers, took up residence in Europe after World War II, for study or to live on a semipermanent basis. Paris, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Stockholm were lively hubs, and all attracted Middleton. He found camaraderie and exhibition opportunities with African American artists living abroad, and through personal correspondence they kept each other informed of the American and international art scenes (fig. 2). Between 1959 and 1961, Middleton lived, worked, and exhibited in Spain, Sweden, and Denmark. “I was traveling around like a gypsy, carrying a suitcase full of newspaper scraps, cards and other bits of paper.”15 Collage painting was becoming his primary mode of expression, and the ephemera of his travels—ticket and transport forms, old newspapers—his media. Active formally, these collage elements are metaphors for movement and cultural exchange, yet their once-inherent temporal and spatial relationships are reconfigured within Middleton’s compositions. In later paintings, his collage materials include postage stamps, concert bills, musical scores, and paper miscellany, some sent by friends to the artist, as well as outdated glossy magazines he collected. Among his favored materials were thick billboard posters he would reclaim and then clean and flatten in his studio through a process of water immersion.

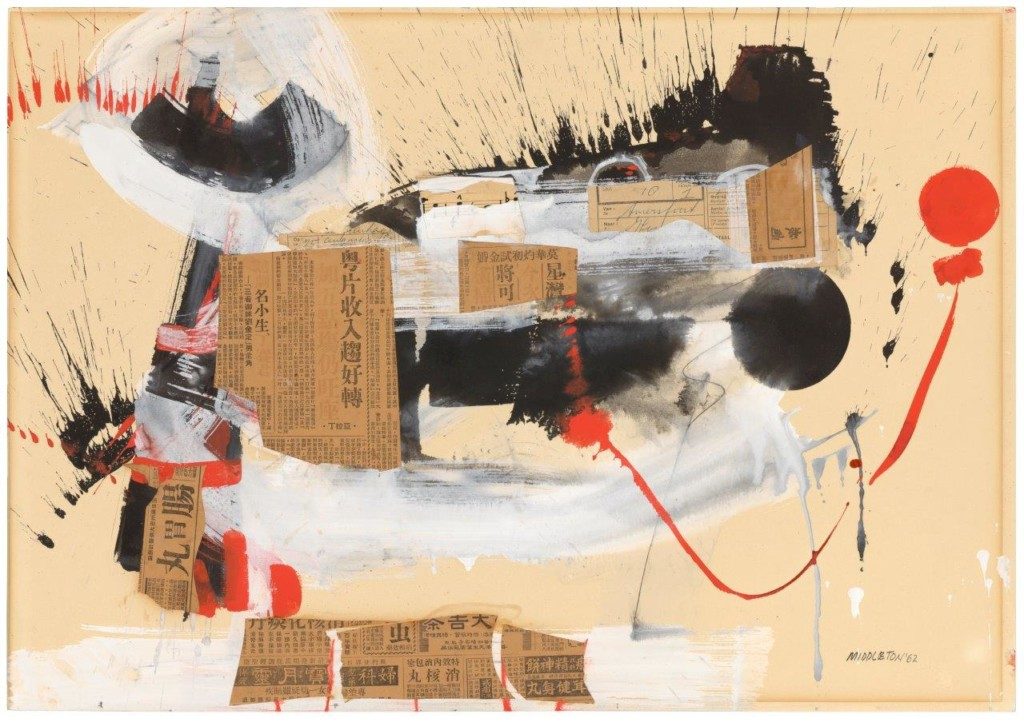

Working between Stockholm and Copenhagen in 1960 to 1961, Middleton’s paintings began to reflect a different energy, intensity, and hue. As Claire Steinmetz remarked, “Middleton built his compositions up from a circle in the center. A short, powerful explosion of color, now for the first time, with wild splashes of paint turning with the movement of the circle . . .”16 Using gouache and other liquid color media, he honed his calligraphic line and let it dance expressively. Arcs of color made with wet and dry brush bop with solid forms of color and collage, both opaque and translucent, as in Hymn to Democracy and Cymbals, both from 1962 (figs. 3, 4). “For the first time, I felt able to leave spaces open, one of the golden rules of Motherwell,” Middleton recalled.17

Beyond the visual absorption of the arts and his environs, Middleton took a serious interest in art history. While in Stockholm, he worked on a treatise about collage, tracing its early history from Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and papier collé to something he called “Collaborations,” collage with paint or any fluid color medium—his beloved combination.18 Cubism, Surrealism, and Dada are discussed, and noted artists include Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, May Ray, Hans Arp, and Max Ernst. The manuscript, with reference notes and call-outs for illustrations, is methodical and differs markedly from the poetry and unpunctuated prose he also wrote about collage.

“In the Beginning,” the first of eight sections, commences with Picasso, a figure “responsible for the challenge that is the concept MODERN . . . and today is still among the most creatively challenging artists working. Modern Art, therefore should always leave a place for him, for it can scar[c]ely ignore Picasso without negating all we know as Modern in Art.”19 Middleton’s written expression throughout the twenty-one typed pages is keenly observational and somewhat technical; first-person interjections are infrequent and appear mostly at the end of sections. The essay, in effect, positions Middleton’s collage paintings in the tradition of the “concept MODERN” with a rationale for “the authenticity of Collage as a true and sincere means of expression and therefore a worthy contribution to the annals of contemporary Art.”20 If the modernist narrative of invention and impudence that informs the essay is Eurocentric and male dominated, it was not qualified in this manner by the author. For Middleton, art had certain universal qualities, but in practice its deliverables were quite individual.

This propensity to script himself, and his work, into a history of modern art and collage, as he understood them, is manifested in the many illustrations of his studio included in the printed materials about his art. Publications of his collages included, from the earliest years onward, photographs of him creating—on the floor, in medias res, and in composed stills of his studio space, evocative of a collage aesthetic. Although some associate collage with creative happenstance, Middleton meticulously regulated his aesthetics and the presentation of his work, such as framing, publications, typeface, and illustrations, and he complained if they were subpar. Middleton’s move to Amsterdam in 1962 brought him into a circle of cutting-edge designers. An invitation to visit came from Willem Sandberg (1897–1984), a Dutch typographer, innovative curator, and director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. As director of the Stedelijk Museum between 1945 and 1963, Sandberg’s pioneering and internationalist leanings were a good match for Middleton; both favored modern and experimental aesthetics. Middleton expected to make contact with galleries and stay a short while; instead, the Netherlands became his base. “I knew at the moment I came here that I should stay.”21

Middleton’s acceptance into the Dutch art world was quick, facilitated by friendships with American sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri (1923–2009), active in the CoBrA movement, and Dutch painter Jef Diederen (1920–2009), who like Tajiri worked in abstraction. His work was associated with Dutch Pop Art in the 1960s, and both he and Gustave Asselbergs (1938–1967) were considered the principal proponents of collage art in the Netherlands.22 By 1964, the date of Social Realism (fig. 5), Middleton had received several solo exhibitions in the Netherlands.23 Benno Premsela (1920–1997), a leading figure in Dutch interior design, assisted with his exhibition installations and secured Middleton’s commissioned Bijenkorf department store windows showcases.24 Among the renowned Dutch graphic designers that Middleton worked with for his publications were Juriaan Schrofer (1926–1990) and Wim Crouwel (b. 1928), both of the multidisciplinary, modernist design studio Total Design, established in Amsterdam in 1963. The geometric, grid-based typefaces developed in the Netherlands were the perfect complement for Middleton’s improvisational aesthetics of the 1960s.

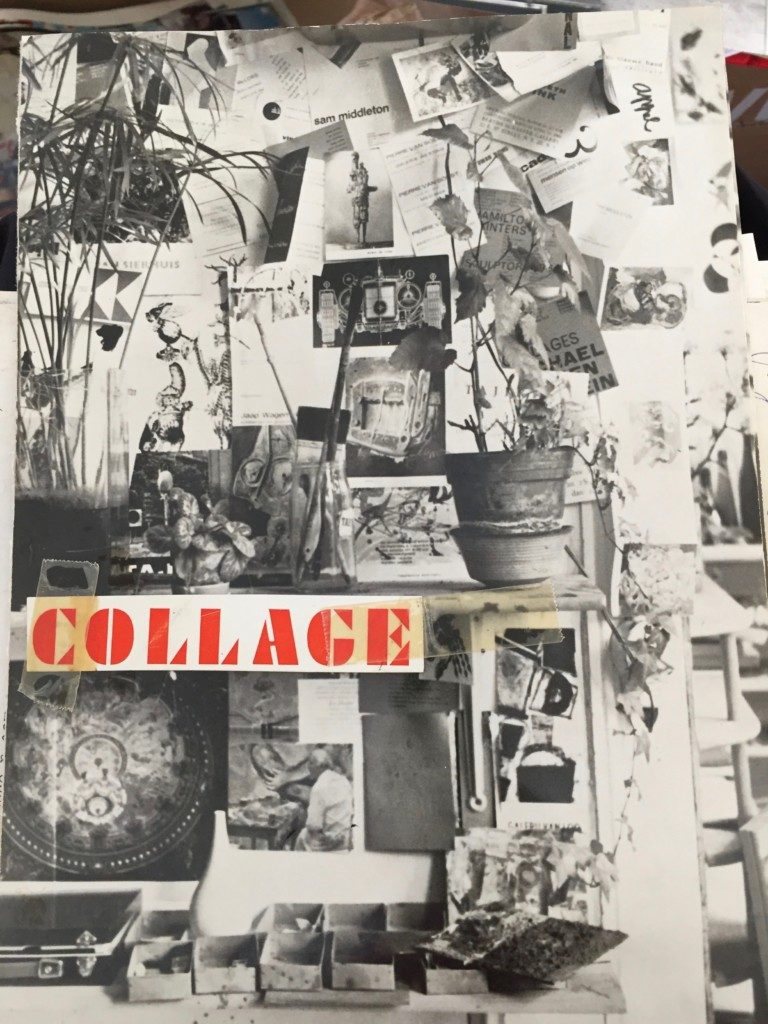

The Middleton archives include a mock-up of a black-and-white photograph of his Amsterdam studio; bits of yellowed tape fix the word “COLLAGE” in a red typeface just off center, along the edge of a shelf (fig. 6). This is the design used for the cover of Impressions From My Atelier/Sam Middleton, self-published in 1967 in Amsterdam: It too is a type of collage art.25 Red is an important and suggestive accent in Middleton’s art. Used here, it signals perhaps the color that is lacking in the black-and-white illustrations. (Publications illustrating Middleton’s collages in the 1960s and early 1970s used limited color, if at all.) A catalogue in the printed publication lists the cover illustration as Wallscape. 1967 Atelier foto. Amsterdam. This is followed by a detail of his studio floor: Floorscape. 1967. Atelier floor. Amsterdam. The twelve-page publication includes “A Round Poem to Collage” and eight works of art in personal, private, and civic collections, each illustrated and accompanied by a poetic phrase.26 The text of the poem, lowercase and without punctuation, is laid out in the form of a circle. The following excerpt is from the end of the poem:

is collage only a medium or something else for the artist is small collages may be small basic soul rudiments collage is the manuscript paper to which a poster symphony is put self contained last dance empty ballroom and the sound of coltrane unique complete work existing intimate revelations. . . . art repeats music expressive rhythm recital depth collage is art is i am.27

Two of the illustrated collages, Bells (1966; Amsterdam collection) and For Don Cherry (1966; artist’s collection) are round (50 cm [19 3/4 in.] in diameter), a favored geometric shape and emblem for Middleton. The circular, sometimes oval, shape represents, as he claimed, “‘the circle of life, of everything that goes around comes around. I interrupt it because I don’t want to go back to Harlem.’”28 In his treatise, Middleton likened collage to a mended mirror, and in Round Poem to Collage, the artist is collage. The little we know about his early New York years is framed by his recollections and tinged with deep melancholy and intermittent bliss. Middleton’s Harlem was oppressive, a place he described as suffocating—a chokehold—from which he needed to escape. Music was his escape, a conduit for joy—which he found in his youth at the Savoy Ballroom, where he perched on the fire escape to hear jazz bands rehearsing.

Burdened by the myriad expectations placed on successful black artists, and on both sides of the Atlantic, Middleton was often asked cumbersome questions related to his departure from New York and reasons for not returning. He and James Baldwin quarreled over artistic freedom and responsibility, and this wrangle haunted the artist.29 He had no desire to return to the United States but instead preferred to steadfastly grow aesthetically and creatively with his remembrances. “That I remember my roots is a plus for my work. . . . But every memory, all of my music is here. There’s nothing to go back for,” Middleton told Graham Lock in 2004.30 Memory for Middleton was bound up with sound, and so too were the geometric orchestrations of his compositions. “Music and musicians have taught me how to think about painting. . . . I found that the lyricism I wanted, the fluidity I wanted, came easier with music than it did with talking to painters.”31

Produced a decade after he began to work in collage, Impressions From My Atelier is a personal offering of important aspects of Middleton’s creative machinations. Every bit of the small publication is instructive: the mix of languages (English and Dutch), the references to music in the poem and the art selections—For Don Cherry, Bells, Opus IV, The Sound of Coltrane, The Last Dance, Atelier Sounds—and the atelier shots. These studio shots are orchestrated stills and aesthetically acoustic. The Middleton atelier was a resonant place where music was a constant companion—noteworthy enough to be remarked upon by myriad writers. John A. Williams reveled in the fact that Middleton carried a record player and records with him while at sea during his Merchant Marine years, suggesting it was where the artist learned to see sound.32 Artist Avon Neal, whom he met in San Miguel de Allende, was duly impressed that Middleton brought a record player and records, jazz and opera, to Mexico by car.33

Middleton’s “Round Poem to Collage” echoes concepts found in his collage treatise, but without punctuation the words resist fixed readings, not unlike his collage paintings: “a bit like memory in patches of objects and things idea and this inner image we see quest and hesitations is the driving force for all art which is without doubt very personal image strange but . . .”34 Readers may follow the text from any entry point, infer punctuation, and stop and start at will. Coherence is subjective. I suggest: Strange but. Art which is without doubt. Very personal image. Collage is art. Art is. I am.

Sam Middleton: those closest to him understood that his art was truly a collaboration of his young life in America, extended by memory through jazz music in particular, and a long and productive creative life in Europe, notably the Netherlands. This is not hard to see when one stops looking for what is expected. In 1963, the Dutch writer Gerrit Kouwenaar compared Middleton’s work with the poetics of American sculptor Shinkichi Tajiri, the Italian painter Afro Basaldella (1912–1976), and the Dutch painter and poet of the CoBrA movement, Lucebert (1924–1994).35 Nearly ten years later, in 1972, Romare Bearden noted: “It is interesting that Mr. Middleton, who came to Europe a decade ago and who has lived, for the most part, in a city whose people and locales were depicted so well by Rembrandt, still retains at the core of his art a way common to his origins.”36 Assessments of Middleton’s art often served the needs of the reviewers: some considered the art in relation to the artist’s contemporaries while others filtered the reception through oblique references to Middleton’s nationality and race. Equally influential were political events in Europe and the United States and trends in European and American art discourse. Parsing this history is a necessary step in a retrospective examination of his career.

Principally self-taught, Middleton’s list of “great inspirations” cleaves to no nation, genre, or profession. Among the many noted by the artist are Robert Schumann, George Gershwin, Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, Wassily Kandinsky, Miles Davis, Emile Nolde, Charlie Parker, Marian Anderson, Mstislav Rostropovich, Noel Coward, Igor Stravinsky, Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline, Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, and Thelonious Monk.37 When he was really jammed, he turned to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

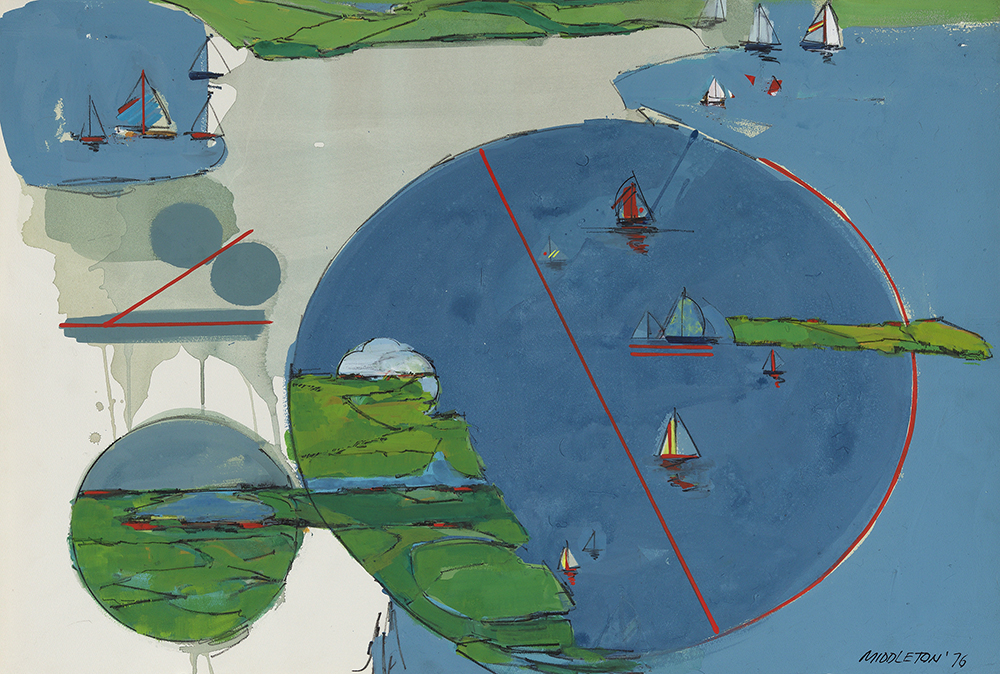

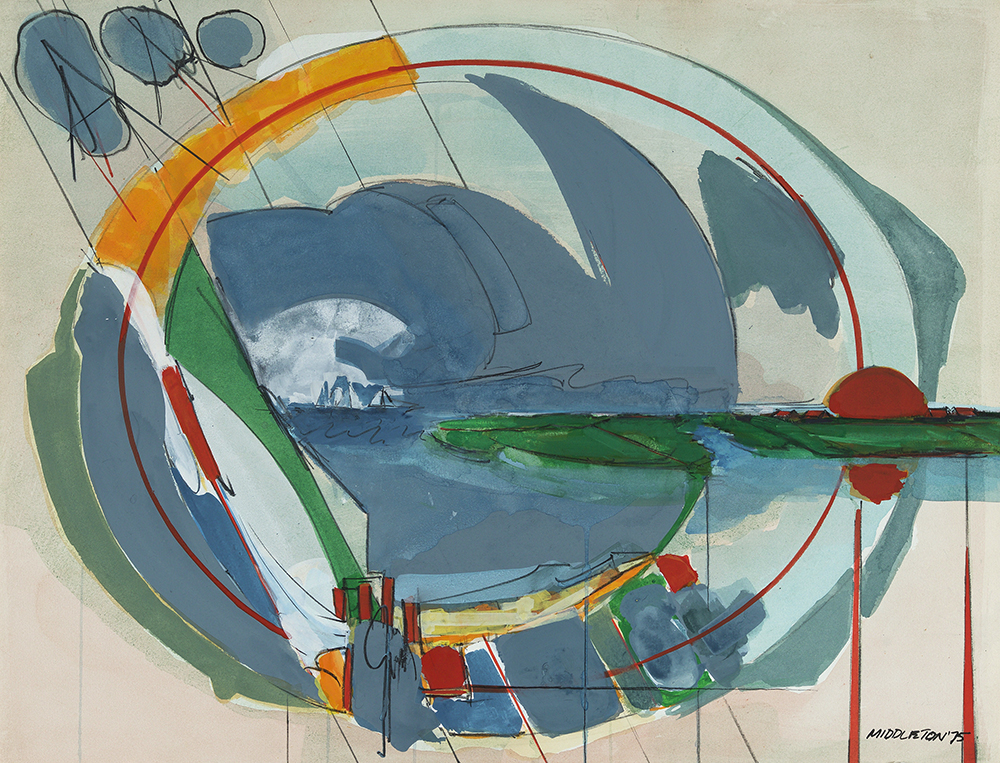

But Middleton’s art was inflected by location—inhabitants, history, geometry, architecture, and color—something he understood and used well. By 1972, Middleton had acquired a farmhouse in Oterleek, North Holland, and the imprint of the flat polder landscape and nearby North Sea provided considerable inspiration for the artist. Watercolor and gouache became the dominant medium for these verdant Dutch land- and seascapes as Middleton worked to capture the sublime qualities of stillness, wind, polder, and sea and the thrill of fresh color: a new blue in particular. Some are populated with drifting sailboats, soaring gulls, and intersecting ovals and circles, such as Summer Wind (fig. 7). Their graceful orchestration and structured repose recall the work of abstract painter Richard Diebenkorn, admired by Middleton. In Everyone’s Music Book (fig. 8), polder, sea, and sky are abstracted into shifting color forms that intersect the circular lines that enclose them. Quintessential Middleton vectors, the articulated geometry of diagonal lines, ovals, and semicircles, were not new elements for Middleton, but the melody expressed in these Oterleek works was. In the Netherlands, Middleton encountered a tradition of painting steeped in the fundamentals of geometry, echoed by its land and architecture, all of which he absorbed and repurposed for his compositional structure. In the studied attention to the light, color, and geometry of his environs, he worked in the tradition of Jacob van Ruisdael, Johannes Vermeer, and Rembrandt van Rijn, and he maintained his singular voice.

In a 1974 letter to Romare Bearden, Middleton inquired if he had yet to make art at his new home and studio in St. Maarten, noting: “History has such an obvious influence in the mentality, pride and character of a place and its inhabitants. . . . I can tell you there are some traits, color and expressions that are strictly and def[i]nitely Dutch. They could not ever be Italian, French or Scand[i]navian. Each is individual and so is Art and the artist.”38 Today we can travel a virtual world instantaneously; Middleton reminds us to consider the place-bound nature of aesthetics, including those attributed to a “European” canon.

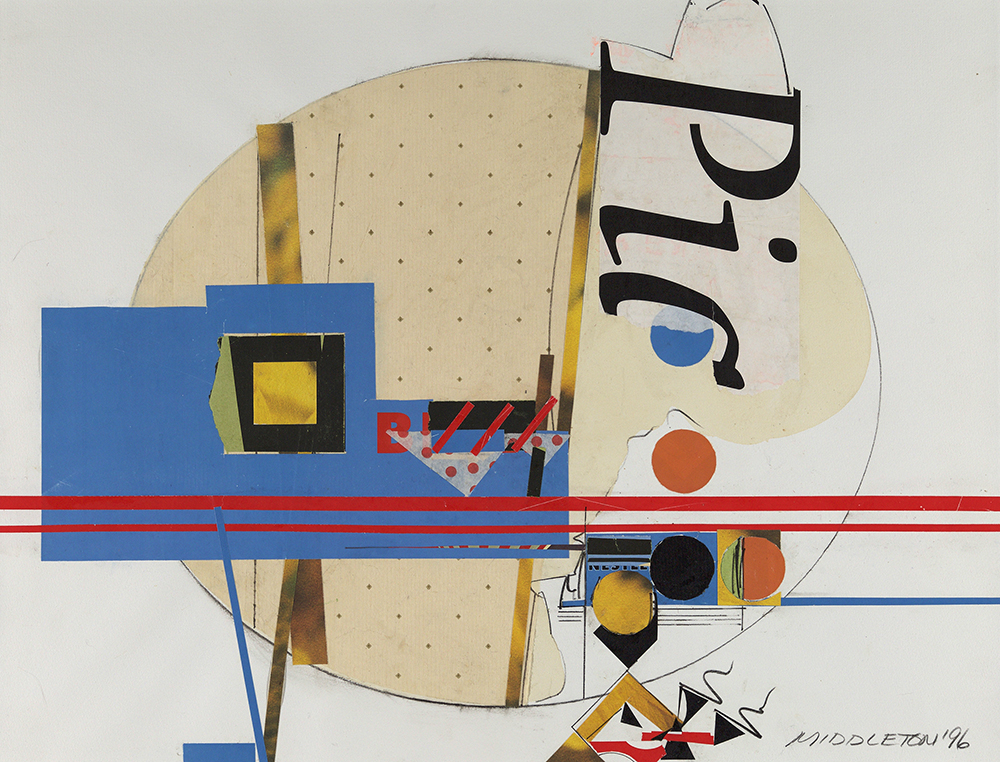

Middleton’s signature style was marvelously generative, not repetitive, and exemplary of his own commentary that “collage is a chain of connecting ideas and expressions.” His 1960s treatise on early collage reappears in Table Top Still Life from 1996 (fig. 9) as a clever visual lesson. Compositional antecedents abound in his oeuvre and that of others, such as Picasso’s legendary oval collage, Still Life with Chair Caning (1912; Musée Picasso, Paris). Indeed, Picasso’s collage was one of the works he discussed early and planned to illustrate in the treatise. It validated the use of “foreign materials” for paintings. “Though a small experiment,” Middleton wrote, it “launched a new concept of textual inconsistencies which were arranged so that a new unity was formed.”39 While Table Top Still Life seems to wink at Synthetic Cubism, Piet Mondrian, and de Stijl, it displays the delight with which the artist played with art history. Printed materials listing artistic genres in Dutch, including sociaal realisme, are the most recognizable components in Social Realism (fig. 5), and Dutch text on van Gogh appears in Cymbals (fig. 3). Middleton marked his place in the history of art. Alongside these artistic traditions, he accepted the gifts that the Netherlands provided: opportunity, professional recognition, a new vocabulary and language, and a vast sky and quality of light he had found nowhere else—all essential for his work. In Holland, he had the freedom to be an American artist, one who used Elmer’s Glue.

Cite this article: Julie L. McGee, “Sam Middleton: Freedom’s Song” in “Riff: African American Artists and the European Canon,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1628.

PDF: McGee, Sam Middleton

Notes

- Important biographical sources include Claire Steinmetz and Samuel M. Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, exh. cat. (Venlo, Netherlands: Museum Van Bommel Van Dam Venlo, 1997) and the documentary by John Albert Jansen and Oogland Filmproducties, Amsterdam, Sam Middleton: Afro-American Artist in the Low Countries, 2014. Access at https://vimeo.com/116346070. I am grateful to Hansje Kalff for her assistance and the privilege to further my research on the artist with information and papers belonging to the estate, cited hereafter as Sam Middleton Estate. ↵

- Sam Middleton, Out Chorus (1960), collage on composition board, 29 7/8 x35 13/16 in. Gift of the Ford Foundation Purchase Program, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. The Ford Foundation purchased the painting from the artist for $450. America Is Hard to See, Whitney Museum of American Art, May 1–September 27, 2015, accessed January 4, 2018, https://whitney.org/Exhibitions/AmericaIsHardToSee. ↵

- “11 American Artists in Spain,” June 1960, Madrid, Spain, Circulo de Bellas Artes; and Contemporary Arts, New York, October 1960. ↵

- Explanatory label text for “Scotch Tape,” one of the twenty-three thematic “chapters” installed throughout the building for the exhibition America Is Hard to See, Whitney Museum of American Art. ↵

- Sam Middleton, “Collage,” undated typescript, 18–19, Sam Middleton Estate. ↵

- Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 23. ↵

- Sam Middleton cited in S. P. Lomax, “Een Artiest in Conflict. Sam Middleton, Amerikaans Schilder in Amsterdam,” Vrij Nederland, April 27, 1963, 9. Middleton frequently recalled Franz Kline’s advice to leave New York. ↵

- Sam Middleton quoted in Forty Artists Under Forty, exh. cat. (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1962), n.p. ↵

- His first solo exhibition was at Galería Excelsior, Mexico City, 1957. ↵

- Avon Neal, “Middleton in Mexico (A Personal Memoir),” undated typescript, 11, Estate of Sam Middleton. ↵

- Stuart Preston, “Art: A Danish Survey,” New York Times, October 15, 1960, https://search-proquest-com.udel.idm.oclc.org/docview/115151241?accountid=10457. ↵

- John I. H. Baur, then associate director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, selected four works from Contemporary Arts for the Whitney traveling exhibition. Lloyd Goodrich and John I. H. Baur, Young America 1960: Thirty American Painters Under Thirty-Six, exh. cat. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger Publishers for the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1960). ↵

- A John Hay Whitney Opportunity Fellowship provided Middleton a stipend of $3,000 from June 1,1959, to May 30, 1960, which he used to support his travel and work in Spain. ↵

- Middleton cited by Graham Lock in “Sam Middleton: The Painter as Improvising Soloist,” in The Hearing Eye: Jazz and Blues Influences in African American Visual Art, eds. Graham Lock and David Murray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009),130. ↵

- Middleton cited in Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 33. ↵

- Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 33. ↵

- Middleton cited in Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 33. ↵

- Middleton, “Collage.” Also see Ruth Link, “Sam’s One-Man Party,” Aftonbladet, February 23,1961. Link mentions the collage book as underway and something Middleton hoped to publish in Sweden. Mentioned in Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 33. ↵

- Middleton, “Collage,” 1. Capitalization is taken from the original text. Although undated, references within the text suggest a timeframe of 1960 to 1965. ↵

- Middleton, “Collage,” 17. ↵

- Sam Middleton cited in Lomax, “Een Artiest in Conflict,” 9. Author’s translation. ↵

- See the foreword by the director of the Museum Van Bommel Van Dam Venlo: Thei Voragen, “Foreword,” in Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 5. See also Frank van de Schoor, Gustave Asselbergs en de Pop Art in Nederland (Nijmegen: Nijmeegs Museum Commanderie van Sint Jan, 1994). ↵

- From 1962 onward, Middleton exhibited continuously in the Netherlands; his first solo show was at Galerie Delta in Rotterdam. ↵

- Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 57, and Hansje Kalff to the author, January 8, 2018. ↵

- Sam Middleton, Impressions From My Atelier: Sam Middleton (Amsterdam: Self published, 1967), 12 (illus.). ↵

- Middleton, Impressions From My Atelier. The list of illustrations appears on page ten. Middleton’s Round Poem to Collage was reprinted in James E. Lewis, Afro-American Artists Abroad, exh. cat. (Washington, DC, The National Collection of Fine Arts of the Smithsonian Institution, 1970), 9. ↵

- Middleton, Impressions From My Atelier, n.p. ↵

- Middleton cited in Steinmetz and Middleton, Sam Middleton: Jazz Voor Ogen, 43. Don Cherry was an American jazz trumpeter and composer. ↵

- Baldwin and Middleton knew each other and planned a joint publication on jazz, the proceeds of which would support CORE. CORE/Middleton Correspondence,1965. Sam Middleton Estate. Middleton’s relationship with African American artists residing in Europe and the United States is taken up in my extended research on the artist. ↵

- Middleton as cited by Lock, “Sam Middleton,” 132. ↵

- Middleton as cited by Lock, “Sam Middleton,” 123. Middleton’s deep regard for music extended beyond jazz and blues, and numerous classical composers and symphonies are honored in his paintings and prints. ↵

- John A. Williams, “‘For Me, Improvisation is a Galaxy of Color. When I Listen to Music I Feel Like a Soloist,’” in Sam Middleton, exh. cat. (Amstelveen: Cultureel Centrum Amstelveen, 1987), n.p. ↵

- Neal, “Middleton in Mexico (A Personal Memoir),” 5–6. Lifelong friends, Middleton and Avon Neal met in Mexico. Middleton drove a “little gray Henry J” from New York to Mexico. ↵

- This is the beginning of the poem. Middleton, Impressions From My Atelier, n.p. ↵

- Sam Middleton: Collages, Schilderijen, Grafiek, exh. cat (Groningen: Groninger Museum voor Stad en Lande, 1963), n.p. The exhibition catalogue included introductory texts, in Dutch, by Gerrit Kouwenaar and S. P. Lomax and typified the artistic circles in which he moved: Dutch and American avant-garde poets, artists, musicians, and dancers. ↵

- Romare Bearden in Sam Middleton, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Fodor Museum, 1972), n.p. ↵

- Personal journal, Sam Middleton Estate. ↵

- Sam Middleton to Romare and Nanette Bearden (carbon copy), February 9, 1974, Sam Middleton Estate. By early 1974 Middleton had settled into the Oterleek farmhouse. ↵

- Middleton, “Collage,” 2. ↵

About the Author(s): Julie L. McGee is Associate Professor in the Department of Africana Studies and Art History and Associate Director of the Interdisciplinary Humanities Research Center at the University of Delaware.