Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition

Curated by: Adrienne L. Childs

Exhibition schedule: Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, February 29, 2020–January 3, 2021

Exhibition catalogue: Adrienne L. Childs, with contributions by Valerie Cassel Oliver and Renee Maurer, and the foreword by Dorothy Kosinski, exh. cat., Washington, DC: Phillips Collection in association with Rizzoli Electa, 2019. 208 pp.; 108 color illus.; 13 b/w illus. Hardcover: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780847866649)

Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition is a must-see exhibition for scholars of American art. The installation is sensitive, dynamic, and revelatory, and the catalogue is a much-needed contribution to scholarship, a primer on modern and contemporary African American artists’ fraught relations with European modernism. Thankfully, it has been extended through the fall of 2020. For those who cannot travel to see the exhibition in person, I hope this review and images will encourage you to seek out the catalogue.

The fact that the exhibition takes place at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, and only there, is important. Since the thesis of the exhibition is that African American twentieth- and twenty-first-century art is in deep dialogue with Europ as the Howard University Gallery of Art or the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, gives an extra charge to the exhibition, and also forces viewers to question the works regularly on view in the permanent collection of the institution. The presence in the exhibition of so many African American artists, both contemporary and modern, in conversation with modernist works made by mostly white male artists from Duncan Phillips’s historic collection, along with significant loans from private and public collections around the country, is deeply significant, as it calls attention to the fact that so many of these artists have been left out of the modernist narratives presented in major American museums. It also provides a possible road map or model to follow for placing contemporary art in fruitful juxtaposition with historic works of art and for centering African American art at the core of the modernist canon.

As curator Adrienne Childs asserts in the opening wall text of the exhibition, “Using humor and satire,” African American artists “created ‘riffs’ to question the supposed superiority of European art, exposing its fraught association with people of color. The push and pull of these relationships became a distinct tradition in African American practice.” The exhibition explores this dynamic between twentieth- and twenty-first-century European modernist and African American artists. The exhibition begins with African American artists taking on that giant of European modernism, Édouard Manet (1832–1883), in the exhibition section Gazing Back at Manet. Included in this section are artists who are in conversation with Manet, while at the same time centralizing the Black female body.

Absolutely stunning works include Robert Colescott’s (1925–2009), Sunday Afternoon with Joaquin Murietta (1980; collection of Arlene and Harold Schnitzer); Mickalene Thomas’s (b. 1971), Le Dejeuner sur L’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010; collection of the artist); and Ayana V. Jackson’s (b. 1977) Judgment of Paris (2018; courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago). All take on Manet’s iconic modernist canvas Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, (1863; Musée d’Orsay) by substituting Black women at the center of the composition. While Colescott replaces Manet’s white nude model with a Black nude model, Thomas and Jackson use photography to make confident clothed Black women the dominant figures of their riffs on Manet. This conversation about the centrality of the Black body is a particularly rich one and should be thought about in tandem with another recent exhibition, Denise Murrell’s field-changing show Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today.1 Like Murrell, Childs draws our attention not only to the Black women’s bodies at the very core of the modernism of Manet, Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), but also to contemporary Black women artists who are spinning that legacy on its head, in the process making some of today’s most exciting American art. As she argues in her catalogue essay on contested bodies: “Canonical images by Manet, Matisse, and Picasso that reference the black body later became touchstones for postmodern female African American artists who, if we consider them collectively, mounted spectacular acts of defiance against such historic works of art. By injecting the black female body, often their own, into modernist compositions, they upended and claimed a place in the ongoing dialogue about representation and the female body.”2 The second section of the exhibition, African Art and Modernism, places both the racist ideologies of modernist European artists looking to l’art negre, or modernist primitivism, in the early twentieth century and contemporary artists working against these ideologies in the postmodern era in the foreground. This section of the exhibition looks at the intertwined connections between African art, European modernism, and African American art. Scholars such as Howard professor Alain Locke (1885–1954) encouraged African American artists to access African art mediated by European modernism, such as the art of the French avant-garde and German Expressionists. Lois Mailou Jones’s (1905–1998) Africa (1935; The Johnson Collection) is a modernist example of this. Contemporary artist John Edmonds’s (b. 1989) tête d’homme (2018; courtesy of the artist and Company, New York) takes on Man Ray’s (1890–1976) iconic Surrealist photograph Noire et blanche (1926; Museum of Modern Art). Edmonds replaces the charged beauty of a Black African mask and white woman model with a luxurious color photograph of a queer Black man posing with a contemporary African-style mask made for the tourist trade. Also in this section, Sanford Biggers’s (b. 1970) quilt work Negerplastik (2016; courtesy Massimo De Carlo) references the 1915 Carl Einstein (1885–1940) book Negerplastik that was so influential on Locke and artists in his circle, such as Hale Woodruff (1900–1980). Biggers, in affixing tar, glitter, and fabric to create a silhouette of a generic African power sculpture on an antique African American quilt, plays with notions of cultural appropriation, reappropriation, and exchange between African and African American artforms.

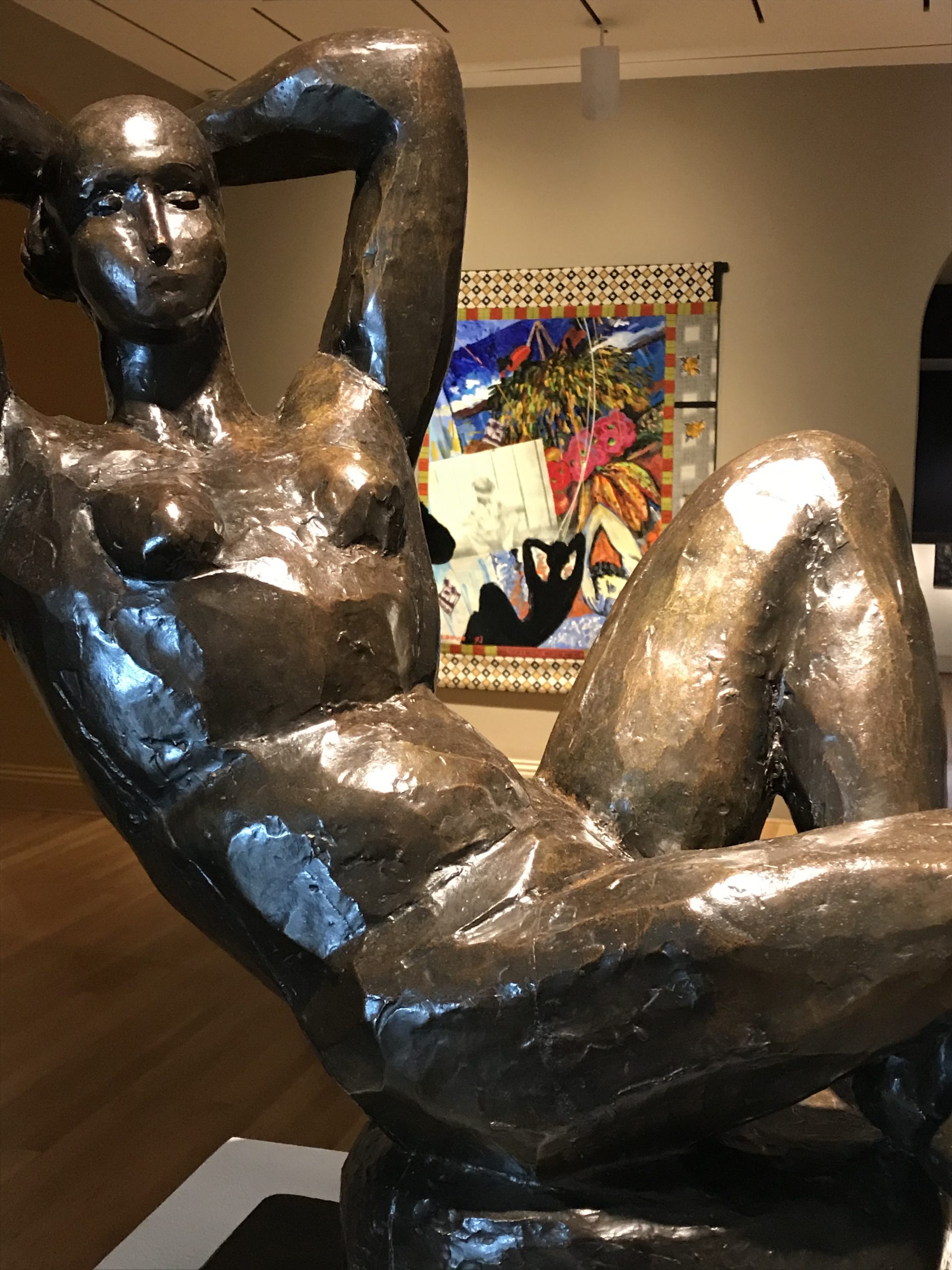

The section Reckoning with Picasso and Matisse forms the nucleus of the exhibition and is masterfully installed. Powerful juxtapositions include Matisse’s Large Seated Nude (1922–29, cast 1930; Baltimore Museum of Art) in conversation with Emma Amos’s (1937–2020) Malcolm X Morley, Matisse and Me (1993, courtesy of RYAN LEE Gallery and Art Finance Partners) and Elizabeth Catlett’s (1915–2012) Ife (2002; Chrysler Museum of Art) (fig. 1). The contrast between the work by Amos and the Matisse sculpture is spectacular because the installation makes it seem as if the large bronze sculpture by Matisse is casting a shadow on the painting on linen by Amos. The shadow of Matisse is literally incorporated and refigured into the painting and fabric work by Amos. Having the Catlett sculpture in this room as well manifests another powerful reappropriation of Matisse’s iconic nude bronze by Catlett, who channels the sculpture of Matisse and Pre-Columbian Mexican sculptors to carve Ife out of mahogany, creating her own Yoruba goddess.

One of the great surprises of the exhibition is Janet Taylor Picket’s (b. 1948) And She Was Born (2017; collection of the artist). The artist made this bold portrait for the exhibition inspired by Matisse’s Interior with Egyptian Curtain (1948; Phillips Collection). And She Was Born is a portrait of a woman born out of the darkness of canvas—the canvas is painted black—but also outside of the frame of art history. In the case of this painting, Picket has based the literal frame or border of the canvas on the pattern of Matisse’s Egyptian curtain, but it is an individual African woman that is her subject.

For me the revelation of the show, the work that took my breath away, is Mequitta Ahuja’s (b. 1976) Xpect (2018; collection of the artist), in which she takes on Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907; Museum of Modern Art) (fig. 2). The canvas is large, filling a whole wall of the exhibition. The artist has centered her own clothed and pregnant body, and she proudly holds a sonogram of her unborn child in front of her as she lounges on velvet-draped chairs. Within the painting is another painting, also by Ajuja, called Le Damn, which includes a self-portrait of the artist, this time weeping. The artist has taken the language and visual forms of Picasso but centralized her own body and her own lived experience, and she has done so on a large scale, claiming space for her body and experience in art history. Of her monumental self-portrait, Ahuja states: “By recasting the figures in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon with my own body, a woman of color as both subject and artist, I reclaim the territory Picasso has borrowed from the black body and from black creative production. I see this as a decolonizing act.”3 In her self-portrait, she celebrates her own body and her triumphant creation of human life, a very different view of sexuality than Picasso’s.

Reframing Impressionism looks at three artists not often brought together: Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937), with Haystacks (c. 1930; Smithsonian American Art Museum). Beauford Delaney (1901–1979), with an untitled work from about 1958 (courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery), and Titus Kaphar (b. 1976), with Pushing Back the Light (2012; collection of Bennet H. Grutman)—all three riffing on Claude Monet (1840–1926). Of the three, Tanner is the artist most readily associated with Impressionism—indeed, his time in Paris coincided with the popularity of the Impressionist movement there, along with the international Symbolist movement. His connection to Monet’s work has long been recognized. Childs’s excellent choice of a deep blue Tanner painting of haystacks underscores his relationship to the French artist.

While Delaney is not usually associated with Monet, the exhibition’s comparison of Delaney’s abstractions to Monet’s late work is convincing. In particular, as I was absorbed in Delaney’s vibrant yellow and blue brushwork, I was reminded of the play of light on Monet’s cathedrals and haystacks. Kaphar’s painting is the one that pushes against the work of Monet the most—literally pulling or pushing back the light-filled canvas of a Monet painting to reveal a “guttural” surface of black tar underneath. This is one of the many powerful riffs in the show, although I think the most compelling work in the exhibition is by women—such as Thomas pushing against Manet, Ahuja against Picasso, and Amos against Matisse.

Two final sections round out the exhibition. Cubist Lineages features work by Romare Bearden (1911–1988), specifically Odysseus: Poseidon, The Sea God-Enemy of Odysseus (1977; The Thompson Collection); and Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976), with Icarus (2016; collection of Debbie and Mitchell Rechler). Both of these works take on not only Cubism, but also Greek mythology—forms and subjects deeply embedded in Western art history. Bearden gives Poseidon the head of an African sculpture, and Thomas uses quilt making and sports jerseys, along with a tip of the hat to Matisse’s iconic cutout profiles, to create a fitting denouement to the exhibition, as it brings together Matisse’s modernism, African American quilt making, and the United States sporting industrial complex—built disproportionately on Black male bodies—together in the depiction of Icarus, a man who flew too high and was burned by the sun. Another disembodied head in this section, in conversation with the Bearden collage, is Wangechi Mutu’s (b. 1972) Mwotajo (The Dreamer) (2016; collection of Carolina Nitsch) (fig. 3). This sculpture looks back to the European sculpture of Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) and Man Ray but is also evocative of Afrofuturist dreamscapes.

The exhibition concludes with the section titled Frank Stewart and Henri Cartier-Bresson. I was particularly taken by the visual and artistic resonance between Cartier-Bresson’s (1908–2004) Matisse (1944; Phillips Collection) and Stewart’s (b. 1949) David Driskell (1980; collection of the artist). Both photographs show the artists seated on the lower left of the composition, with examples of African textiles or sculpture above their heads, seemingly occupying their dream space, or a space for creative play and influence. Stewart’s homage to David Driskell (1931–2020) in his home surrounded by his collection is all the more poignant, as the American art community has just lost Driskell to COVID-19 in the space of time that the exhibition opened and was closed to the public due to the pandemic.

The handsomely illustrated catalogue is the recipient of the fifth Annual James A. Porter & David C. Driskell Book Award from the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visuals Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland. In addition to the foreword, acknowledgments, and introduction, it includes two essays written by Childs, “African Art and the Modern” and “Contested Bodies: Artist/Model/Muse”; an essay by Phillips Collection curator Renee Maurer, “Duncan Phillips and Community,” which illuminates the fruitful relationship between Phillips and Howard University; and a conversation, “Abstract Relations,” between Childs and Valerie Cassel Oliver, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Virginia Museum of the Fine Arts. Interspersed throughout these essays are artists’ statements by Kaphar, Driskell, Edmonds, Biggers, Barbara Chase-Ribaud, Janet Taylor Pickee, Ahuja, Jackson, Moe Brooker, Thomas, Leonardo Drew, and Jennie C. Jones paired with full-page images of their works in the exhibition. A checklist of the exhibition, an index, and a helpful list of further reading are included in the back matter of the catalogue.

Cite this article: Anna O. Marley, review of “Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition,” Phillips Collection, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10748.

PDF: Marley, review of Riffs and Relations

Notes

- This exhibition was held at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in New York, from October 24, 2018–February 10, 2019. ↵

- Adrienne L. Childs et al., Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Phillips Collection in association with Rizzoli Electa, 2019), 71. ↵

- Childs, Riffs and Relations, 100. ↵

About the Author(s): Anna O. Marley is the Kenneth R. Woodcock Curator of Historical American Art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts