Integrating Disruption: Acquiring the Philip J. and Suzanne Schiller Collection of American Social Commentary Art, 1930–1970

Please note that images in this article may be disturbing to readers.

The Columbus Museum of Art has enjoyed a longstanding reputation for the strength of its American collection. This is due on one hand to a gift of American modernism by Ferdinand Howald (1856–1934) in 1931, which includes major works by Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Morton Schamberg, and Charles Sheeler, among others. Over the years, the museum has worked to fill gaps in this area, namely by acquiring modernist sculpture, such as Elie Nadelman’s Host, 1920–23, and John Storr’s, Architectural Form No. 3, c. 1923, as well as selected paintings, including John Marin’s New York Series,1927. On the other hand, the museum collection has been also rich in American Scene painting, grounded by an important and deep collection of works by Columbus native George Bellows. This connection to Bellows directed purchases of cohorts, such as Reginald Marsh, Hudson Bay Fur Company, 1932, and Edward Hopper, Morning Sun, 1952.

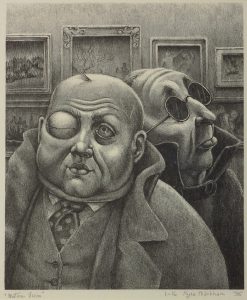

In 2005, the Museum acquired the Philip and Suzanne Schiller Collection of American Social Commentary Art, with works ranging from 1930 to 1970. The collection, which is comprised of eighty-four paintings, three hundred and seventy-four prints, and one sculpture, has numerous strengths. It represents a longer than typical narrative of social engagement that moves consistently from the Social Realism of Philip Evergood, Joe Jones, and Jacob Lawrence (fig. 1) of the 1930s, through to the 1960s, with works by Romare Bearden, Joseph Hirsch, and Peter Saul. Another strength of the collection is its inclusion of the variations of Surrealism that emerged in the United States, including Social Surrealism of O. Louis Guglielmi, James Guy (fig. 2), and Walter Quirt; Magic Realism of Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and George Tooker (fig. 3); and the Salvador Dalí-esque work of Federico Castellón (fig. 4), that resulted as American artists encountered the work of Dalí at the Julien Levy Gallery and Wadsworth Atheneum in the 1930s. The large component of prints include works by artists such as Peggy Bacon, Leonard Baskin, Thomas Hart Benton, Mabel Dwight, Boris Gorelick, Rockwell Kent, Louis Lozowick, and Kyra Markham (fig. 5). Significantly, as many of these examples demonstrate, the collection includes a higher number of artists marginalized by race, sexuality, gender, and class, than are generally represented in the American art historical canon.

While the content of the Schiller Collection might seem to be a departure from the other strengths of the American collection, in fact, it closely aligns with a number of museum acquisitions and exhibitions during the years preceding the acquisition of the Schiller Collection. In 2001, the museum purchased a group of photographs by members of the New York Photo League, which constituted the largest public collection of that group in the country. Earlier Social Realist and Surrealist acquisitions include works by Paul Cadmus, Archibald Motley, Priscilla Roberts, and John Wilde. In 2002, the museum acquired a collection of lithographs by George Bellows from Dr. and Mrs. Harold Rifkin, many of which are quite direct in their social commentary. The museum also had already established a practice of organizing exhibitions that brought attention to lesser known artists, such as Middleton Manigault: Visionary Modernist, in 2001, or exploring lesser studied movements, such as Regionalism, as in Illusions of Eden: Visions of the American Heartland in 2000.

In acquiring the Schiller Collection, however, the museum was considering making the second most expensive purchase in its history toward a group of relatively unknown artists whose compositions had difficult, and to many in the museum community, unappealing content; five years were spent in strategy and community engagement to complete the acquisition. Reaching out to the community for financial support of an acquisition is certainly nothing new, however, the museum did not ask for financial support, but instead solicited support for the content of the collection. The directions and process that were settled upon were not innovative in and of themselves, but they did prove effective.

The collection was brought to a wide continuum of communities that were often outside of the committed patron base, speaking to groups and individuals about the strengths of the collection and especially about the ability of the collection to create open dialogues between the museum and its audiences. The museum engaged with the city’s gay, black, Jewish, and religious communities to talk about the legacy and representation that artists such as George Tooker, Jared French, Jacob Lawrence, and Raphael Soyer exemplified. For instance, there was very frank talk about one of the more difficult works, Joe Jones’s American Justice (fig. 6). The painting, completed in 1933, had served as an important model for artists who participated in the NAACP and the John Reed Clubs’ anti-lynching exhibitions in 1935. There was discussion about how the work could speak empathetically to a shared and difficult American history—and American present. The support these dialogues generated proved directly influential in the decision process of the museum board.

There was also frank discussion about funding the acquisition of the Schiller Collection, which was to occur by deaccessioning one of two works by Thomas Eakins in the museum collection—his large 1899 painting, Wrestlers. It is quite telling that deciding not to keep a work by a major canonical artist got far greater attention in the American art world than did the merits of deciding to acquire a collection of works that could challenge and transform that canon.

One of the important decisions made early on in negotiating the acquisition with the Schillers was to acquire essentially the entire collection, instead of selecting only the better known works. While works in the collection constitute a wide range of achievement, the importance of the collection content and its historical context is not necessarily best reflected by the handful of its better known artists, but instead by the aggregate effect of all of the approaches and trajectories. The acquisition also included all of the Schiller’s prints, which represent an important component of the period and also are a reflection of the wider diversity of artists working during its chronological parameters.

The museum has made very conscientious refinements to the collection since its purchase. An oil study by Walter Quirt, Obeisance to Poverty, 1936–38, which was part of the collection acquisition, was deaccessioned to enable the museum to acquire another Quirt painting, The Future is Ours, 1935, a much better representation of the artist’s interests and style. Scholar Janet Wolff has written quite compellingly about the process by which figurative works of art are feminized and consequently subjected to an aesthetic judgment that denigrates them as not of “museum quality.”[1] While the museum clearly decided that there was a better representation of Quirt’s production, this refinement was quite emphatically not operating within the power dynamics at the focus of Wolff’s essay. A group of unknowns was not deaccessioned for a canonical artist, as so often happens, but instead, the decision was part of a commitment to refine the collection with “like for like.”

With the acquisition complete, the most pressing issue for the museum was how to announce this significant realignment of the American collection. Assuming the role as the responsible steward of its content meant a serious and long-term commitment of institutional financial and intellectual resources. The first step was to get works installed in the galleries. The collection does not lend itself to celebratory exhibitions, as the shared social engagement of the works results in lessening the impact of individual paintings when too many are installed side by side. The Schiller Collection is at its visual and conceptual strongest when it is in a dialogue with the broader American collection that allows it to reshape the expected narrative. Luckily, the acquisition came at the beginning of an extended period of shifting and reinstalling galleries to accommodate a renovation taking part in three phases, and construction for the new wing of the museum.

During this period, the museum content team experimented with a varied series of gallery installation ideas for short periods of time—such as in employing themed galleries, as in The City, Artists Against Injustice, or Love and War. This proved enormously conducive to allowing relationships and narratives to emerge within a collection so profoundly changed by a single acquisition. Works such as those in the Schiller Collection are rarely allowed to dominate the trajectory of an installation. They are included in the margins and as supporting works, but seldom carry the spaces. Both the museum content team and administration were willing to support this exploratory process, which at times resulted in major works, such as the Hopper, giving up the expected center wall position.

The next issue in stewarding this collection was that simply changing gallery installations in a museum in Columbus, Ohio, would not announce this important shift in narrative and collection as readily as in an urban center, so it can really only be part of the process. And, a significant number of the works and artists were little known, so it was particularly important that whatever inroads were made in raising awareness of them would not depend on an individual curator or on the particular shape of the institution at that given time. If the efforts to introduce these works remained associated with a single individual, then once that individual left the institution—as, in fact, I now have—the change would fold in on itself and end or diminish considerably.

While it is absolutely worth making that marginalized position quite clear, I think that constantly labeling artists from the position of the disempowered and marginalized only strengthens the structure that maintains that disempowerment. I prefer simply (or not so simply) to naturalize the position of these artists. I realize this is often easier to say as a curator in Columbus, Ohio. For instance, no one asked me where the Roberto Matta, Arshile Gorky, or Jackson Pollock was when I titled an installation American Surrealism that only included Boston Expressionists, Magic Realist, and Social Surrealists, as if this is the norm.

One strategy of announcing the Schiller Collection and initiating the participation in the broader American narrative that could be self-sustaining was to establish an annual symposium, called The Art of Concern, that would explore topics central to works and themes in the collection. While symposia may not always be the best venue for engagement, given the midwestern location of the city of Columbus they enabled a broad range of scholars to see these works in person. Invited speakers included scholars working in the specific areas mirroring those of the Schiller Collection, but many speakers were scholars who otherwise would not necessarily have come across this material. The museum also began to focus exhibitions on the works. In 2006, Robert Cozzolino, Marshall Price, and I curated George Tooker: A Retrospective. In 2017, an exhibition, Subversion and Surrealism in the Art of Honoré Sharrer, will open that was co-curated with Cozzolino. The museum also organized an exhibition of the local, socially engaged printmaker, Sid Chafetz, who has gained a higher profile due to being more frequently included in the galleries with works from the Schiller Collection.

So, in conclusion, the success of the acquisition of the Schiller Collection was that the institution was able to move outside of its closest art community for content support. And, the museum became vested in establishing a broad-based, self-sustaining dialogue that includes these works representing these artists. One marker of the success of this endeavor is that this article is now perpetuating this dialogue on a more expansive national level that will hopefully serve as an example that will take root within other institutions.

All illustrations are from the Columbus Museum of Art

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1564

PDF: Wolfe – Integrating Disruption

About the Author(s): M. Melissa Wolfe is Curator of American Art at the Saint Louis Art Museum.