New Discovery: Robert S. Duncanson’s Ruins of Carthage (1845)

“Wealth has engendered a taste for the arts, and its inhabitants seem to be peeping out of the transition state, and entering upon one of taste and refinement. . . . Cincinnati can boast of her artists.”1 So wrote William Adams, a Zanesville, Ohio, resident, to his friend, painter Thomas Cole, when Adams visited the Queen City in 1842. Now Cincinnati is beaming again in the wake of Dr. Jill Biden’s selection of Robert S. Duncanson’s (1821–1872) Landscape with Rainbow (1859, Smithsonian American Art Museum) as the inaugural painting on January 20, 2021. This momentous occasion prompts deeper investigation of this internationally acclaimed artist. Here I will be examining one work in particular, Duncanson’s 1845 Ruins of Carthage (fig. 1). Although a digital image of the painting has been available on the internet since January 2009 (at ohiomemory.org), until now no scholar has published a reproduction or contextual analysis of this African American painter’s first romantic landscape, which was inaccessible in private hands for well over 120 years, in small institutions for about half a century, and never exhibited in an art museum.

My former undergraduate student Emily Rebmann learned about the painting while working as a site historian for the Ohio History Connection, and she mentioned it to me this past fall. I then emailed Patty Ketner, the widow of Duncanson’s biographer, art historian Joseph D. Ketner. She confirmed that Ketner first learned the location of the painting almost two decades after the publication of his book in 1993 but had neither examined it in person nor written about it.2 In early January 2021, I drove to Georgetown, Ohio, where the painting now hangs, unlabeled, in the Uysses S. Grant Boyhood Home, to examine it and take close-up photographs.

In this essay, I will briefly analyze the Ruins of Carthage, contextualize it in terms of the subject and similar compositions by other artists, consider its intersections with African American political activism, and provide some biographical information about its owners. I argue that with this work Duncanson established some of the hallmarks for which he became internationally recognized, including the use of literary sources, imagined settings in ancient civilizations, Claudian compositions, sets of pairs and/or opposites, and small pairs of foreground viewers, one of whom gestures with an outstretched arm toward the vista. More significantly, I assert that by depicting a celebrated African site singled out by African Americans at an 1843 state convention in Michigan as proof that “we are worthy of the name of American citizens,” as asserted by Committee Chairman William Lambert,3 Duncanson was expressing race pride and alliance with African Americans seeking enfranchisement. When he signed his name for the first time on the front of the canvas, he was not only marking a transition in his career but personally testifying for human and civil rights.

Visual and Literary Analysis and Context

Carthage was a Phoenician city-state founded in the first millennium BCE on the coast of what is today Tunisia. Before the Punic Wars with Rome (264–146 BCE), it was the largest and most powerful and affluent political entity in the Mediterranean. (“Punic” derives from “Punicus,” Latin for “Carthaginian.”) In the Third Punic War (149–146 BCE), Rome conquered Carthage and burned the city to the ground. Later, Julius Caesar rebuilt the city as a strategic seaport of the Roman Empire. Vandals, Byzantines, Muslims, and Crusaders subsequently occupied the city.

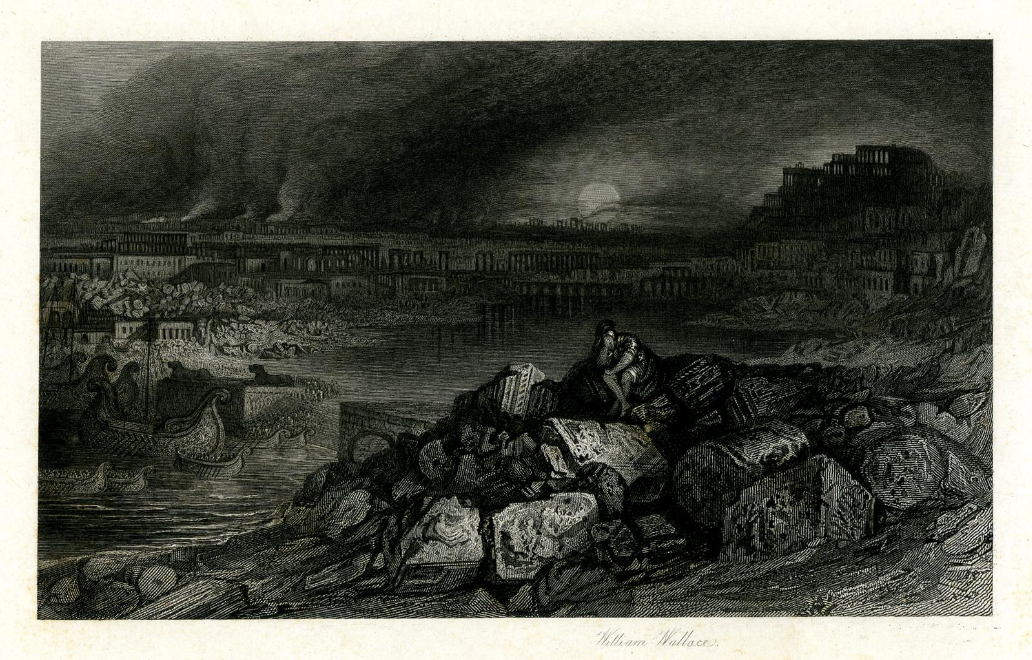

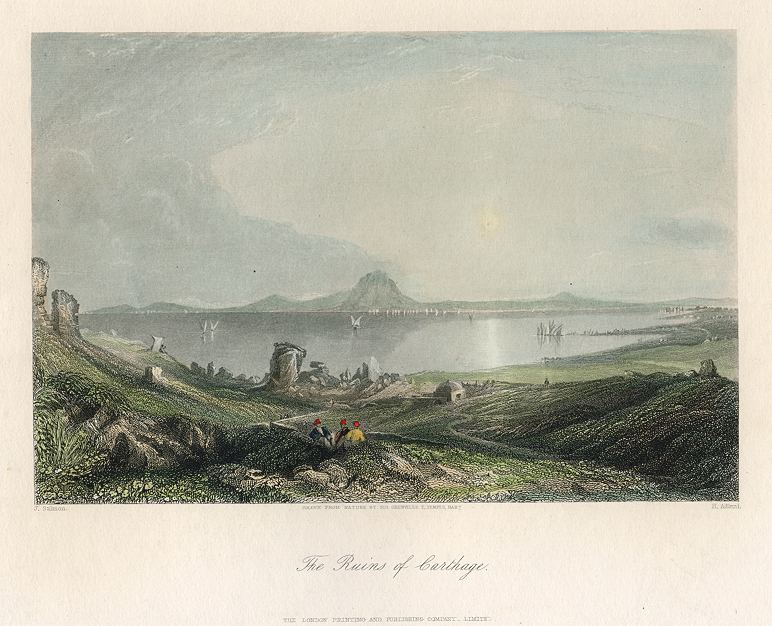

There are several possible visual and literary sources for Duncanson’s composition. Danish naval officer and explorer Christian Tuxen Falbe (1791–1849) produced the first archaeological survey map of the ancient site in Recherches sur l’emplacement de Carthage (Paris, 1833). The same year, William Wallis’s (1796–ca. 1829) print Caius Marcius [Gauis Marius] Mourning Over the Ruins of Carthage, after John Martin, appeared in the London literary and artistic annual The Keepsake (fig. 2).4 In 1837, Falbe traveled to Tunisia with Major Sir Grenville Temple (1799–1847), who had already published his impressions of the ruins in Excursions in the Mediterranean: Algiers and Tunis (1835). Excerpts from this book, along with an 1837 print by Henry Adlard (1799–1893), The Ruins of Carthage (after John Francis Salmon, ca. 1808–1886; fig. 3), and a poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon (1802–1838), “Carthage,” appeared in Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book (London) in 1837.5 Duncanson’s painting predates the version of Adlard’s popular work that appeared in the New York edition of the German-language Meyer’s Universum (1850).

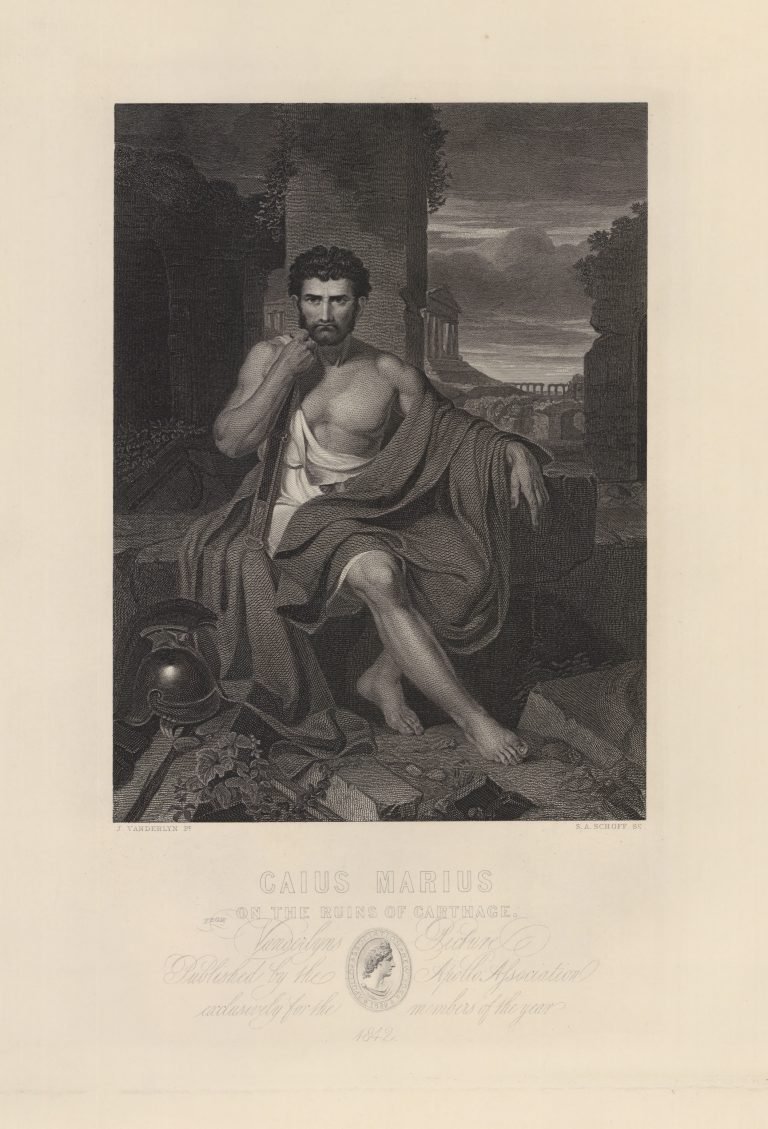

Although J. M. W. Turner (England, 1775–1851) had painted his Decline of the Carthaginian Empire in 1817, it was not until 1859 that prints were made after it, meaning that Duncanson could not have seen the composition. Awareness of Carthage grew in the United States after 1842, when the American Art-Union circulated thousands of copies of Stephen Alonzo Schoff’s (1818–1904) engraving Marius on the Ruins of Carthage (fig. 4), which was made after John Vanderlyn’s (1775–1852) oil on canvas of the same name (1807, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, copied by Samuel Morse in 1811 and Asher B. Durand in 1842).

Duncanson’s vision departs radically from that of Vanderlyn, for whom the figure of Gauis (ca. 157–86 BCE), a Roman general exiled to Carthage in 87 BCE, dominates the foreground, and of Martin (England, 1789–1854), who features the contemplative leader at a distance, seated atop a heap of ruins in the moonlight. Ruins of Carthage is more akin to Adlard’s print. In both images, a slightly cloudy sky dominates the upper two-thirds of the composition, while tiny people in the foreground look out at a calm Gulf of Tunis. Adlard presents a contemporary, populated view of North Africa in a sweeping, unbounded panorama; three seated men wearing turbans, perhaps Arab residents, converse at midday, while multiple boats sail in the harbor. By contrast, Duncanson offers a more focused, poetic scene of a deserted coast approaching sunset; long shadows on the sandy shore extend past low ruins and rocks, some highlighted with small dabs of white impasto. In the lower left are rather clumsily rendered pale-skinned figures (fig. 5). A man wearing a shiny hat or helmet and a red cloak sits, hunched forward, on an architectural fragment. This is probably Marius; a similar red cloak and helmet appear in Vanderlyn’s representation and in multiple other paintings of the military leader.6 A woman with long golden-brown hair, wearing a white dress, touches the man’s shoulder and gestures toward the horizon. Such body language is common in landscapes classified as “prospects.” The animated, clothed bodies of these two human figures contrast with the two stiff marble male nudes atop columns in the middle ground. Like the woman, one statue gestures with its arm toward the sea. The other sculptural figure holds a long spear, evoking Carthage’s violent history.

In the center of the picturesque painting, broken columns, cisterns, and buildings, softly brushed in pink and light blue, seem to dissolve in the moist Mediterranean air. A mass of overgrowth encroaches on the left. À la Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), Duncanson framed the composition, but rather than using trees he did so with two large Ionic columns, each topped by a profusion of flowering vines. The massive column on the right edge, almost reaching the top of the composition, is a jarringly dark silhouette against the pastel middle ground and background. “Light and shade,” which may have been an alternate title for the painting, is an apt description.7 The sharp contrasts may reflect Duncanson’s developing mastery of color values. While the sunset symbolizes the demise of a civilization, the soothing palette, glowing light, and abundant flora suggest new life and hope for the future.

As in paintings by Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and other artists of the Hudson River School, Duncanson repeated the motif of a pair of viewers, one gesturing outward, in multiple later works, including Summer (1849); three of the murals for Nicholas Longworth’s home, Belmont, now the Taft Museum of Art (ca. 1850–52); Uncle Tom and Little Eva (1853); The Temple of the Sibyl (1859); The Rainbow (1859); and Mountain Pool (1870). He would explore further themes of decimated places in paintings such as Mayan Ruins, Yucatan (1848), Pompeii (1855), Land of the Lotus Eaters (1861), Vesuvius and Pompeii (1870), and Pompeii (1871). Desolation, the final painting in Cole’s five-part The Course of Empire series (1833–36), which depicts a moonlit scene with a column overgrown with foliage in the foreground, may have influenced Duncanson.8 Additionally, in 1862, Duncanson would repeat the motif of a female figure in a white dress gesturing skyward in a painting of Calliope (now called Faith), the Greek goddess of heroic poetry.

Political Context

As a self-taught artist, Duncanson had begun his fine art painting career just four years earlier, producing only about a dozen other known works during this time, including several portraits, two still lifes, the trial of Shakespeare, a miser, and the infant Savior (the last three after prints). He first showed his work in Cincinnati at the Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge in 1842. At the 1844 Mechanics’ Institute Fair, Duncanson exhibited several copies after prints that local critics noted favorably. That year, on commission, he produced his first landscape painting, a distant view of a country manor. Yet Duncanson had difficulty competing with established white artists in Cincinnati, such as James Beard (1811–1893), Miner Kellogg (1814–1889), Thomas Buchanan Read (1822–1872), and the brothers John and Godfrey Frankenstein (1817–1881 and 1820–1873).

In the fall of 1845, Duncanson was an itinerant painter, but by December he had settled in Detroit near his hometown of Monroe, where he had worked as a house painter and glazier. Now Duncanson advertised himself as a “Portrait and Historical Painter,” boldly asserting, “Portraits warranted, and finely executed, or no pay.”9 It is likely that while here Duncanson painted Battle-ground of the River Raisin (current location unknown), a site in Monroe where the Battle of Frenchtown took place during the War of 1812.10 According to Ketner, the painter remained in Michigan until May 1846, when he returned to the Queen City.11 It is probable that Duncanson produced Ruins of Carthage before the 1845–46 trip, inspired by a significant gathering of African American men two years prior. Duncanson may have considered contemporary politics in light of ancient history. He must have been aware of the State Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of Michigan, held in Detroit October 26–27, 1843, and he may even have attended it. Ketner does not account for Duncanson’s whereabouts in 1843 but asserts, “Although he established his career in Cincinnati, he always maintained close family ties to Monroe.”12 For decades, Duncanson spent summers there on sketching trips, and it is possible that the painter was in Monroe for part of that year, which would have put him conveniently close to the convention in Detroit.

At the convention, committee chair William Lambert called on African Americans to “band ourselves together and wage unceasing war against the high-handed wrongs of the hideous monster Tyranny.”13 He spoke out against taxation without representation, demanding “Equal Political Rights.”14 Lambert declared:

Our condition as a people in ancient times, was far from indicating intellectual or moral inferiority. For, we are informed by the writings of Herodotus, Pindar, Aeschylus, and many other ancient historians, that Egypt and Ethiopia held the most conspicuous places amongst the nations of the earth. Their princes were wealthy and powerful, and their people distinguished for their profound learning and wisdom.15

He went on to claim that:

Tyre and Carthage, the most industrious, wealthy and polished states of their time, were also once founded by Ethiopians and Egyptian colonies and peopled by blacks. . . . The sun of civilization rose from the centre of Africa, and like the bright luminary of the celestial regions, it cast its light into the most remote corners of the earth, giving arts, sciences and intellectual improvement, to all that lay beneath its elevating rays.16

Those “elevating rays” are apparent in Duncanson’s painting and also may represent a moral divide between heaven and earth and between well-governed African cities of the past and oppressive slaveholding societies. Lambert’s evocation of Carthage was so inspirational that his phrasing would be repeated at conventions of formerly enslaved and freeborn African Americans throughout Ohio during the subsequent two decades, in Columbus (1850), Cleveland (1854), and Xenia (1865).17

Duncanson’s imagined scene of Carthage in decline evokes the romantic pathos of the texts that accompanied Adlard’s print. In his Excursions, Temple recalled his visit: “I beheld nothing more than a few scattered and shapeless masses of masonry. The scene that was once animated by the presence of nearly a million of warlike inhabitants is now buried in the silence of the grave.”18 As an African American living just across the Ohio River from slavery, Duncanson was probably pondering the fate of immoral civilizations as he made this work. In her poem “Carthage,” Landon lamented,

Time’s eternal wing

Hath around those ruins cast

The dark presence of the past

[ . . . ]

Thou dost build thy home on sand,

And the palace-girdled strand

Fadeth like a dream.

Thy great victories only show

All is nothingness below.19

Duncanson’s red signature and date in the lower right are visible in raking light. The artist consistently signed works on the front of his canvases beginning in 1848.20 This seems to be the first time he did so, and it may indicate his increasing confidence in his technical ability and choice of subject matter not directly derived from others’ compositions in prints, as well as his political sympathies in favor of enfranchisement and against slavery.

While Duncanson was not politically active in a public, demonstrable way (his name appears nowhere in local abolitionist societies),21 he nonetheless supported freedom-seeking causes. For instance, he donated a painting for auction at an anti-slavery society’s fundraising ball.22 He also produced a scene from chapter 22 of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). An Episcopalian rector, lawyer, editor, and ardent abolitionist, the Reverend James Francis Conover (who moved from Cincinnati to Detroit in 1853), commissioned Duncanson to paint the work, the artist’s only known depiction of an African American subject.23 It features little Eva teaching Tom, a man enslaved by her family, to read the Bible. Like the woman in Ruins of Carthage, she wears a white dress and gestures outward to the sky above a body of water, thereby foreshadowing her death and journey heavenward. The scene represents spiritual salvation for Eva and for enslaved persons, as well as physical emancipation for the latter. In 1855, Duncanson probably teamed with James Presley Ball (1825–1902), listed as a “daguerreotype artist” in the 1853 city directory, on Ball’s mammoth painted panorama on the violence of slavery and the trade in enslaved people.24 From about 1853 to 1857, Duncanson worked with Ball, hand-coloring photographic images.25 Ball exhibited this remarkable abolitionist work in both Cincinnati and Boston. While this collaboration seems to have marked the end of the painter’s activism, more information may come to light. When Duncanson’s oldest son, Reuben, accused his father of passing for white to advance his social and economic stature, Duncanson firmly denied it. In an 1871 letter to Reuben, Duncanson declared, “My heart has always been with the down-trodden race.”26

Provenance

There is no record of Ruins of Carthage in an exhibition. An early resident of Cincinnati, the wealthy real estate and steamboat speculator and abolitionist Philip Grandin (1794–1858), seems to have been the first owner of the painting, probably buying it directly from Duncanson just after he completed it.27 Grandin was a silent partner to his brother-in-law, who, in 1816, established John H. Piatt & Co., the first private bank west of the Alleghenies. Once mayor of the village of Maineville, Ohio, Grandin owned large tracts of land in Cincinnati. He was a member of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society and entered several varieties of pears and Columbia peaches in the group’s first exhibition in 1843.28 Fellow Horticultural Society members and abolitionists, cofounders Freeman G. Cary, Andrew Ernst, and Nicholas Longworth, commissioned portraits of themselves from Duncanson (Cary in 1856 and Ernst and Longworth in 1858) and probably appreciated the artist’s still lifes of fruit.29 The painting was passed on to Grandin’s grandson, John Piatt Grandin Jr., and then to his great-grandson, Harry Eastman Grandin (d. 1946), who moved to California in 1945.30 Harry Grandin’s widow, Alma Irene Moss Grandin (1887–1983), who died in Lebanon, Ohio, about thirty miles north of Cincinnati, kept the painting briefly in Huntington Beach. Cincinnatian Marie P. Dickoré (1883–1964) had the work by the late 1940s. A military historian, Dickoré wrote several books, including The Founding of Cincinnati (1912), General Joseph Kerr of Chillicothe (1941), and The Order of the Purple Heart (1943). By 1951, Dickoré gave the painting to the Warren County Historical Society Museum (WCHSM) in Lebanon, Ohio; she was friendly with the museum’s founding director, Hazel Spencer Phillips. For years, the painting was on display in the Glendower Mansion, then the headquarters of the WCHSM, in Lebanon.31 As the stewardship of the mansion changed hands over the years, Ruins of Carthage was subsequently housed at different regional cultural institutions. By 1972, it was held at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati. In the early 1970s, staff at the Stowe House placed some items, evidently including Ruins in Carthage, in storage at Fort Ancient Earthworks and Nature Preserve.32

Around 1990, Fort Ancient held a yard sale, and Ruins of Carthage—its history by then forgotten—was put up for sale. Fort Ancient’s site manager, Jack Blosser, bought it for ten dollars “because he liked the frame.”33 He subsequently left it unexamined for a decade in an upstairs storage area in his home. He rediscovered the painting while preparing to convert the area into an entertainment space for his daughters. After having the painting appraised, Blosser gave it to the Ohio History Connection in 2001, declaring, “You do the right thing. You can’t put a value on your integrity.”34 Yoder Conservation in Cleveland conserved the painting in January 2002, and it has been on view in Georgetown since the renovation of the Ulysses S. Grant Boyhood Home in 2012.

New Directions

Ruins in Carthage was Duncanson’s first Romantic landscape and apparently also his first history scene on an easel canvas. In addition to the reasons suggested above, there may be more reasons why Duncanson envisioned a North African scene. A small neighborhood in the Mill Creek Valley in Cincinnati, about eight miles north of downtown, is called Carthage. It was settled in the early 1790s, and in the early 1840s it was the site of several Democratic conventions covered in local newspapers.35 In 1842, Hamilton County commissioners created a graded road from Vine Street in Cincinnati to Carthage; “the result was the famous Carthage Road, at the time the most pleasant drive out of the Queen City.”36 Travelers also made the journey via boat on the Miami and Erie Canal (built 1825–45). Visitors flocked to see the governors of Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois speak, as well as speeches by Henry Clay, William Henry Harrison, Bellamy Storer, Tom Corwin, and other dignitaries. Carthage was “the great rallying place for the Methodists, the Campbellites, as they were called, the Millerites, and some others; and . . . [it] was known for its religious gatherings, as well as for its political meetings, horse races, fairs, and militia musters.”37

Duncanson also may have prompted other artists to depict the ancient Carthage, such as fellow Cincinnatian Miner Kellogg (1814–1889), who would produce a watercolor of the seaport in 1854.38 Further research may reveal what other images and texts about the Mediterranean seaport were available to Duncanson and others in southwest Ohio at the time he painted Ruins of Carthage. By 1840, another of Cincinnati’s nicknames was “the Literary Emporium of the West.”39 A important publishing center, the city was home to the H. W. Derby Company; the Western Methodist Book Concern; Moore, Wilstach, Keys and Company; W. B. Smith and Company; and at least a dozen other smaller firms. They produced schoolbooks (notably, the McGuffey Readers) and books on religion, travel, history, and fiction. Having conducted extensive research on James Presley Ball in Cincinnati, London, Vidalia, Greenville, Minneapolis, Seattle, and Honolulu since the early 1990s, I anticipate expanding my presentations and publications on the studio photographer, particularly his business venture with Duncanson and their joint abolitionist activities.40

I am also eager to learn more about Duncanson’s paintings during the 1840s and 1850s, a good number of which are still in private hands in southwest Ohio. I am particularly intrigued by the “chemical paintings” he and someone known only by the last name of Coates produced in 1844.41 They exhibited “four splendid views after the singular style of Daguerre,”42 which may have been dioramas.43 The pair created scenes on light-sensitive, chemically treated surfaces that developed in a gradually illuminated auditorium, causing thrilling lighting effects. For a quarter, viewers could see images of the Hagia Sophia, the Last Supper, the destruction of Nineveh, and Belshazzar’s feast, all with musical accompaniment. The topics suggest prints after John Martin’s paintings, which featured dramatic contrasts of light and dark. Duncanson could have seen a mezzotint engraving of Martin’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1821) that was available beginning in 1826. The newspaper description of Duncanson and Coates’s Nineveh is particularly relevant to Duncanson’s interests: “The city being the most beautiful of its age, makes the destruction more awful and interesting. In the first scene, is a view of this city previous to its destruction, and the changes which ensue when the dreadful conflagration is beheld and the Assyrian Army are seen battering down the walls of the city—together with the consternation and dismay of the King and his Counsellors, presents altogether a spectacle the most imposing. This picture is indescribably grand.”44

In his 1843 treatise, Lambert had singled out not only Carthage but additional ancient cities: “The great Assyrian empire of the once powerful Babylon and Nineveh, were once founded by Ethiopian colonies and peopled by blacks.”45 It seems clear that Duncanson was roused by Lambert’s declarations about the notable achievements of people from the African diaspora: “Our condition as a people in ancient times, was far from indicating intellectual or moral inferiority. . . . Therefore, fellow citizens, proscribe us no longer, by holding us in a degraded light, on account of natural inferiority, but rather extend to us our free born right, the Elective Franchise, which invigorates the soul and expands the mental powers of a free and independent people.”46

Duncanson lived to see enfranchisement (at least for African American men) with the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, before passing away in 1872. With the inauguration of the first woman of color as Vice President of the United States in 2021, on the bicentennial of Duncanson’s birth, it is now especially important to highlight the discovery of Duncanson’s testimony to the historic quest for African American enfranchisement.

Cite this article: Theresa Leininger-Miller, “New Discovery: Robert S. Duncanson’s Ruins of Carthage (1845),” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11698.

PDF: Leininger-Miller, New Discovery

Notes

I extend warm thanks to the following for providing information for this essay: Nancy Bailey, Allen Bernard, Emily Burns, Michael Coyan, Kate Crawford, Elisabeth Fraser, Brian Hack, Patty Ketner, Walter Langsam, Brian S. Miller, Kent Mulcahy, Emily Rebmann, Jessica Skwire Routhier, Betty Ann Smiddy, Erin Pauwels, Larry Richmond, Alan Wallach, and Monica Williams-Mitchell.

- As quoted in Lillian B. Miller, Patrons and Patriotism: The Encouragement of Fine Arts in the United States, 1790–1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 196. ↵

- Patty Ketner, email to author, November 19, 2020, including Joseph Ketner’s handwritten notes of a phone conversation with Jack Blosser. Used with Patty Ketner’s permission (email to author, January 23, 2001). Joseph Ketner published a skeletal provenance of Ruins of Carthage in The Emergence of the African-American Artist: Robert Duncanson, 1821–1872 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1993), 191. ↵

- Philip S. Foner and George E. Walker, eds., The Proceedings of the Black State Conventions, 1840–1865 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1979; originally published Detroit: William Harsha, 1843), 1:194. ↵

- Facsimile, accompanied by Letitia Elizabeth Landon’s poem “Marius at the Ruins of Carthage,” accessed January 21, 2021, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Poems_of_Letitia_Elizabeth_Landon_(L._E._L.)_in_The_Keepsake,_1833/Marius_at_the_Ruins_of_Carthage. In a December 2020 email, curator Gary Simons explained the variant spelling of Wallis as Wallace on the print, though not the variant spelling of Gauis Marius in the print’s title. Website of the British Museum, accessed January 21, 2021, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1868-0822-2999. Also, the date of this print is as given in The Keepsake, although Wallis seems to have passed away around 1829. John Martin’s watercolor (1828) is in The Morgan Library & Museum. ↵

- Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book (London: Fisher, Son, & Co., 1837): 38. Adlard’s print was also published in Spirito Battelli, ed., Il Mediterraneo Illustrato (Florence, Italy, 1841). ↵

- Examples include paintings by Tiepolo (1729; Metropolitan Museum of Art); Joseph Kremer (eighteenth century; sold at Christie’s, January 25, 2011, in sale 2511, Old Master & 19th Century Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors Part II, lot 187); François Gérard (1789; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston); Pierre-Joseph François (ca. 1791–94; Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium); and Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret (1807; Dayton Art Institute). ↵

- James A. Porter, “Robert S. Duncanson: Midwestern Romantic-Realist,” Art in America 39, no. 3 (October 1951): 109. This is the only instance of the alternate name, and Porter does not indicate its source. He briefly describes the work but did not reproduce it. Like Ketner, Porter probably never saw the original. The first mention of the painting in print, as Ruins of Carthage, is in Charles Cist, Sketches and Statistics in Cincinnati in 1851 (Cincinnati: William H. Moore, 1851), 126. ↵

- Duncanson copied James Smillie’s 1831 print of Thomas Cole’s Garden of Eden (1828; Amon Carter Museum, Forth Worth). He also copied Smillie’s 1852 print of Cole’s Dream of Arcadia (1838; Denver Art Museum). For Smillie’s print of the Garden of Eden, see Ellwood C. Parry III, Thomas Cole: Ambition and Imagination (Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1988), 72. For Smillie’s Dream of Arcadia and its influence on Duncanson, see J. Gray Sweeney, “The Advantages of Genius and Virtue: Thomas Cole’s Influence, 1848–1858,” in Thomas Cole: Landscape into History, ed. William H. Truettner and Alan Wallach (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the National Museum of American Art, 1994), 130. ↵

- Detroit Free Press, December 16, 1845, 2, as quoted in Ketner, Emergence of the African American Artist, 18. ↵

- Cist, Sketches and Statistics, 126. Cist lists this painting, along with Ruins of Carthage and three others, as the artist’s historical pieces. ↵

- Ketner, Emergence of the African American Artist, 18. ↵

- Ketner, Emergence of the African American Artist, 14. Ketner asserts that the Duncansons established the first extended family of African Americans in the Monroe area (12), and states that Dennis Au has surmised that the clan arrived in Monroe around 1830 (208n5). ↵

- Foner and Walker, Proceedings of the Black State, 192. ↵

- Foner and Walker, Proceedings of the Black State, 194. ↵

- Foner and Walker, Proceedings of the Black State, 193. ↵

- Foner and Walker, Proceedings of the Black State, 194. ↵

- See the Center for Black Digital Reserch, Pennsylvania State University, “Colored Conventions Project,” accessed February 20, 2021, https://coloredconventions.org. ↵

- Facsimile of Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book (see note 4). ↵

- Facsimile of Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book. ↵

- Jack Blosser to Joseph Ketner, January 27, 2000, reiterating a telephone conversation between the men. Collection of Patty Ketner. ↵

- According to local historian Betty Ann Smiddy. Email to author, February 2, 2021. ↵

- Betty Ann Smiddy to author, February 2, 2021. Smiddy could not recall the date. ↵

- Ketner, Emergence of the African American Artist, 46. ↵

- Guy McElroy, Robert S. Duncanson: A Centennial Exhibition (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1972), 11. ↵

- William’s Cincinnati Directory, 1853 (Cincinnati: Williams, 1853), 107. ↵

- Duncanson to Reuben Duncanson, June 28, 1871, private collection, Cincinnati, Ohio, quoted in Ketner, Emergence of the African American Artist, 94. ↵

- Porter states that Grandin acquired the painting from Duncanson in 1845 but does not provide a source (Porter, “Robert S. Duncanson,” 109). This contradicts Cist, who in 1851 names ten of Duncanson’s early patrons (but not Grandin), as well as five of the artist’s historical pieces, including Ruins of Carthage, indicating that Grandin may have purchased the work in the 1850s (Cist, Sketches and Statistics, 126). ↵

- “Reports of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society,” Daily Cincinnati Enquirer, November 6, 1843, 2. ↵

- Shana Klein, “Cultivating Fruit and Equality: The Still-Life Paintings of Robert Duncanson,” American Art 29, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 65–85; esp. 71–72. ↵

- “Harry E. Grandin Expires; Scion of Family Prominent in Early History of City,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 18, 1946, 12. ↵

- My thanks to Michael Coyan, Executive Director of the Warren County Historical Society, for sharing this information over the phone. He also informed me that Dickoré lectured at the society on September 26, 1949, and gifted the museum “with several items,” as she wrote in her diary, now in the collection of the society. Coyan to author, January 27, 2021. Coyan found an additional (undated?) diary entry of a “landscape with ruins.” Coyan to author, February 24, 2021. ↵

- “Garage Sale Painting Worth $33,000,” The Newark Advocate, June 14, 2001, 10. My thanks to Emily Rebmann for sending this clipping. See also Jenny Callison, “Valued Art Work Surfaces,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 19, 2001, B3. My thanks to Larry Richmond for sharing this source. ↵

- “Valued art work surfaces.” ↵

- “Garage Sale Painting.” ↵

- See, for example, “Carthage Convention,” Daily Cincinnati Enquirer, August 10, 1843, 2; and “Mass Meeting,” Cincinnati Gazette, July 13, 1844, 2. ↵

- Ohio Writers’ Program, Cincinnati: A Guide to the Queen City and Its Neighbors (Cincinnati: Wiesen-Hart Press, 1943; reprint, Cincinnati: John S. Swift, 1965), 410. ↵

- Henry A. Ford, History of Hamilton County, Ohio, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches (Salem: Higginson Book Co., 1993), 336. ↵

- Antiquarian interest intensified after Gustave Flaubert published the historical novel Salammbô (1862), set in Carthage in the third century BCE. Other nineteenth-century American artists who depicted Carthage include Joshua Shaw (n.d.), Susan C. Waters (ca. 1852), Mary Elizabeth Church (ca. 1870), Samuel Colman (n.d.), D. Jerome Elwell (1871 and 1879), and Amanda Butterfield (ca. 1875). This listing is from the Smithsonian Institution Research Information System: https://siris-artinventories.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?profile=. My thanks to Brian Hack for sending this link. ↵

- Robert C. Vitz, The Queen and the Arts: Cultural Life in Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989), 56. ↵

- Please see my exhibition review of An American Journey: The Life and Photography of James Presley Ball, Cincinnati Museum Center (May 1–October 24, 2010), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 10, no. 2 (Autumn 2011), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn11/review-of-an-american-journey-the-life-and-photography-of-james-presley-ball, as well as my reference guide entries in African American National Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 244–45; and Thomas Riggs, ed., St. James Guide to) Black Artists (Detroit: St. James Press, 1997), 28–29. ↵

- According to librarian Monica Williams-Mitchell, it is possible that this was the English-born abolitionist William Coates, who had a watchmaking and taxidermy business in Cincinnati in the 1840s. Email to author, February 22, 2021. ↵

- “Chemical Paintings, at Concert Hall, Over the Post Office,” TriWeekly Cincinnati Gazette, April 9, 1844, 3. ↵

- For an analysis of Daguerre’s sole extant diorama, see Theresa Leininger-Miller, “Daguerre’s Recently Renovated Diorama (ca. 1843) in Bry-sur-Marne, France,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 13, no. 1 (Spring 2014), https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring14/leininger-miller-reviews-daguerre-s-sole-extant-diorama-recently-restored. ↵

- “Chemical Paintings.” ↵

- Foner and Walker, Proceedings of the Black State, 194. ↵

- Foner and Walker, Proceedings of the Black State, 194. ↵

About the Author(s): Theresa Leininger-Miller is Professor in the School of Art, University of Cincinnati