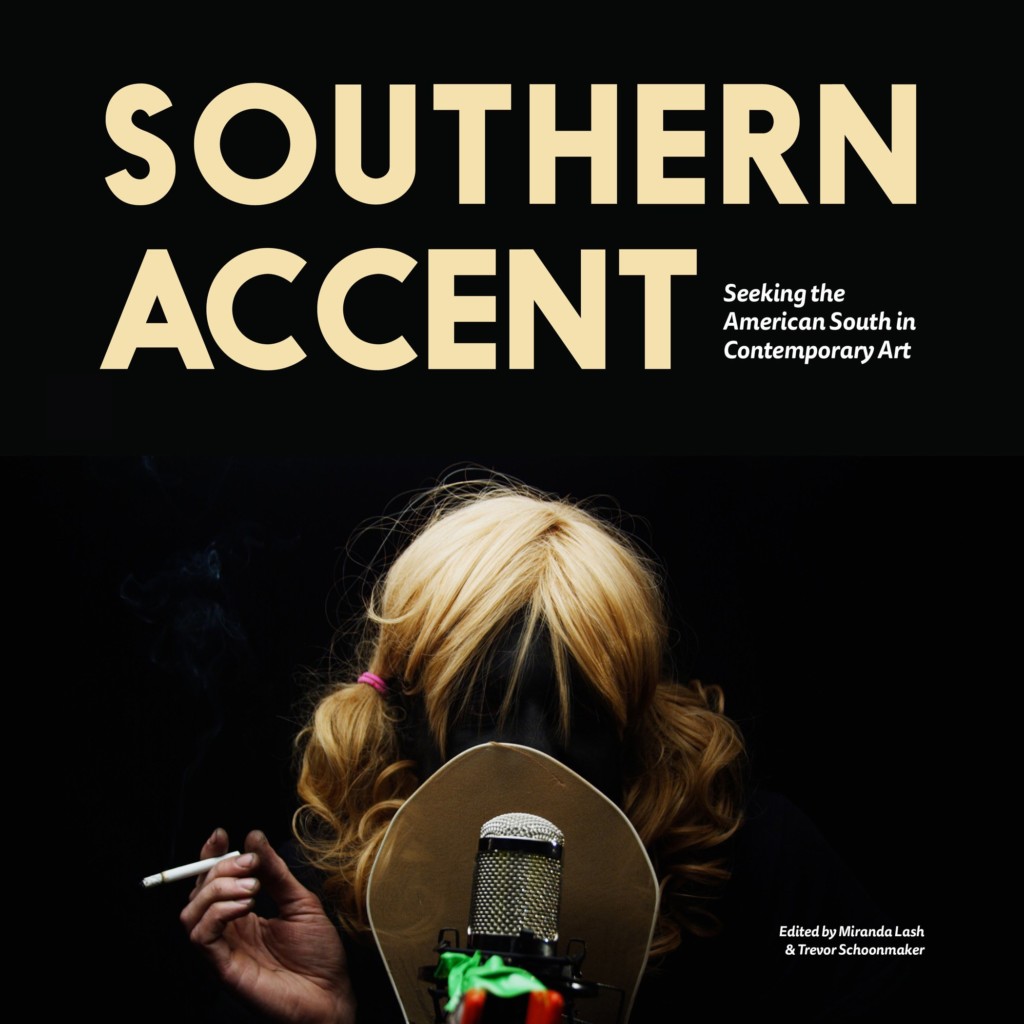

Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art

Edited by Miranda Lash and Trevor Schoonmaker

Durham: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2016; 276 pp.; 336 color illus.; ISBN: 978-0-938989-38-7; Softcover $22.95

Exhibition schedule: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, September 1, 2016–January 8, 2017; Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky, April 29–August 20, 2017

In the exhibition catalogue Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art, editors Miranda Lash and Trevor Schoonmaker, along with their contributors, present a new way of looking at contemporary art produced from 1950 to the present by both southern artists and artists who live outside of the geographic region. Each of their selected artists embodies a southern perspective—one that explores physical, intellectual, or spiritual aspects associated with the South. Those who have had the opportunity to view the exhibition at one of its two venues, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and the Speed Art Museum, were confronted with an ambitious, dynamic, and engaging installation that demonstrated the diversity of art from the region and revealed how ideas about “the South” have permeated beyond its geographic borders, often in thought-provoking ways. The curators assert that their aim was not to present a definitive vision of Southern art, but rather to highlight numerous contemporary artistic interpretations. They refreshingly combined documentary, fine art, and self-taught works—in media whose range included drawing, installation, painting, photography, sculpture, and video—without asserting a narrative or material hierarchy. The catalogue propels these ideas forward, stripping away cultural or disciplinary biases in order to illustrate the ways in which the South has an identity that is simultaneously its own and wholly American. This unique character, particularly in the contemporary era, is shaped by the politics of the Civil Rights Movement and through a precise cultural overlap between food, music, literature, and the visual arts. Southern Accent unmasks long-held ideas about the South and lays bare what most Southerners inherently know, even if they have difficulty articulating it: namely, that the South is complex and contradictory. While it cannot escape from its troubled historical past, its art celebrates the rich and varied traditions that comprise Southern culture. As the subtitle, “Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art,” indicates, the South concurrently embodies romantic ideals and harsh truths and is not easily identified or classified. Instead, as the authors acknowledge, the South is indefinable, a slippery but powerful concept. As Lash explains, southern identity is “a construct that is performative rather than fixed and innate,” and therefore, although they seek to distinguish what the South is now through contemporary art, there is no fixed or unified answer (21).

In the exhibition catalogue Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art, editors Miranda Lash and Trevor Schoonmaker, along with their contributors, present a new way of looking at contemporary art produced from 1950 to the present by both southern artists and artists who live outside of the geographic region. Each of their selected artists embodies a southern perspective—one that explores physical, intellectual, or spiritual aspects associated with the South. Those who have had the opportunity to view the exhibition at one of its two venues, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University and the Speed Art Museum, were confronted with an ambitious, dynamic, and engaging installation that demonstrated the diversity of art from the region and revealed how ideas about “the South” have permeated beyond its geographic borders, often in thought-provoking ways. The curators assert that their aim was not to present a definitive vision of Southern art, but rather to highlight numerous contemporary artistic interpretations. They refreshingly combined documentary, fine art, and self-taught works—in media whose range included drawing, installation, painting, photography, sculpture, and video—without asserting a narrative or material hierarchy. The catalogue propels these ideas forward, stripping away cultural or disciplinary biases in order to illustrate the ways in which the South has an identity that is simultaneously its own and wholly American. This unique character, particularly in the contemporary era, is shaped by the politics of the Civil Rights Movement and through a precise cultural overlap between food, music, literature, and the visual arts. Southern Accent unmasks long-held ideas about the South and lays bare what most Southerners inherently know, even if they have difficulty articulating it: namely, that the South is complex and contradictory. While it cannot escape from its troubled historical past, its art celebrates the rich and varied traditions that comprise Southern culture. As the subtitle, “Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art,” indicates, the South concurrently embodies romantic ideals and harsh truths and is not easily identified or classified. Instead, as the authors acknowledge, the South is indefinable, a slippery but powerful concept. As Lash explains, southern identity is “a construct that is performative rather than fixed and innate,” and therefore, although they seek to distinguish what the South is now through contemporary art, there is no fixed or unified answer (21).

Traditionally, exhibition catalogues function as the only public documentation of an exhibition and feature reproductions of the artists’ work alongside a contextual overview, becoming either a valuable scholarly resource or a beautiful coffee table book. However, Southern Accent is far more than simply a documentary exercise. Beginning with substantive essays by Lash and Schoonmaker, the volume introduces sixty different artists and showcases work created within the last thirty years, although a few are from as early as 1950. While the catalogue includes a fully illustrated checklist, each image is also prominently reproduced elsewhere, alongside contextual images and documentary photographs. Finally, the catalogue also considers the South beyond the visual arts. The lengthy back matter includes a sampling of music featured in the exhibition listening library, spanning recordings from the 1950s to today, a comprehensive chronology of scholarship on Southern art, and a reading list of twentieth- and twenty-first–century fiction that has shaped how the South is both viewed and experienced. What distinguishes this publication from other exhibition catalogues, however, is the middle section, in which twenty-four artists, poets, curators, and scholars address their own experiences of the South in short, highly personalized contributions.

In the opening essay, “What Do We Envision When We Talk About the South?” Miranda Lash draws from an Edward L. Ayers essay that argues that the South is not a discrete entity, but one that is undergoing constant change.1 Building upon this idea, Lash weaves together different strands of thinking on the American South from noted scholars, including Karl Marx and James Cobb, artists, and other individuals, in order to investigate the myths and realities of the South. By identifying these various strands of thinking about the South, Lash ably portrays the reality of this place in contrast to stereotypes found in popular culture, such as reality television shows that feature alligator hunters, beauty queens, or moonshiners. She also stresses that in the art world, the South is often only considered peripherally, except for self-taught, outsider, or visionary artists. In order to change this perspective, she conceives of several themes that embody the complex construct of the South: the impact of history, the flavors of home, spirituality and Sunday morning church, Saturday night revelry, and finding wonder and beauty in the landscape. Lash perceptively utilizes works of art to refute or support these varying threads. For example, Lash highlights Skylar Fein’s Black Flag (for Elizabeth’s) (2008; Collection of Dathel and Tommy Coleman, New Orleans, Louisiana) as an example of an artist paying tribute to a popular soul food restaurant from his New Orleans neighborhood. This work illustrates how southerners relate to place through the taste and memory of food. On a more serious note, to explore both the impact of history and where we are now, she discusses Sonya Clark’s Unraveling (2015– ), a sculptural performative work wherein Clark and volunteers slowly pull apart, thread by thread, a Confederate battle flag. This work considers and confronts various symbols whose meanings have shifted in our current era. Throughout her essay, Lash ties works of art to various touchstones in history and popular culture in order to create a narrative of a time and place not easily characterized.

With deft fluidity, Schoonmaker extends the ideas outlined in Lash’s contribution in his essay, “Southern Accent: The Sound of Seeing.” He lays out the overriding thematic and conceptual framework of the exhibition as “unique creativity (specifically a folk aesthetic, music, cuisine, and storytelling), religion and spirituality, timelessness and tradition, home and landscape, ghosts of the past, injustice and struggle, and the changing face of the South” (61). Schoonmaker aligns himself with writer William Faulkner, who identified the South as “not so much a ‘geographical place’ but as an ‘emotional idea’” (56). This is a key concept, as it illustrates several points: first, the South extends beyond the geographic lines of a specific region; second, it exists in the individual and shared personal and cultural experiences of its inhabitants; and third, it is based not only on the personal experiences of those within the South but also on the perceptions of those outside of it who conjure up a particular idea of the South. Schoonmaker examines the magic and mystique of the South and its tragic and transformative histories and triumphs through the lens of his own experiences as a Southerner in order to bring the South into focus.

In their essays, Lash and Schoonmaker propose that Southern Accent is a timely exhibition and publication. It is. As witnessed by current discussions around the role of Confederate statuary in public areas and the work of movements such as Black Lives Matter to start conversations about racial injustice, we, as a nation, are currently reconsidering our past and, in particular, historical events that occurred in the South, in order to reevaluate what that history might mean for our present and our future. The South is haunted by its history and unable to escape its past. As Schoonmaker explains: “[It] is the most complicated region of the United States—culturally, racially, and economically—and for reasons both justified and overly simplistic, no other place in the county has been more vilified or romanticized” (55). The contemporary artists featured here are also haunted by the complexity of the South, and through their art they bring attention to its traumatic history as a way to begin working through these thorny issues.

Both Lash and Schoonmaker state that the exhibition, and by extension, the catalogue, “begins with the premise of the South as a question rather than an answer” (19). Do they formulate a response to this question? Yes and no. What they present, through their scholarly essays and the shorter contributions that follow, is a multifaceted narrative that reveals the diversity of the region, proving some of the surrounding myths of the South while deflating others. These other contributors—comprised of contemporary artists, art historians, poets, and scholars—write candidly about how their experiences with the South have affected or shaped their work. This mixture of scholarly insight with personal accounts, which address race, humanity, poverty, generosity, alternative lifestyles, and the wider flavor of the South, presents a rich diversity of Southern viewpoints and breaks apart stereotypes. Standouts include a conversation between artists Kara Walker and Ari Marcopoulous about their trip to Stone Mountain, a Confederate monument carved into a mountainside in Georgia. This is illustrated with one of Walker’s works on paper, The Plantation Fambly Romance (1997; Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York), and snapshots of their visit. In contrast, art historian Richard J. Powell’s contribution “Porch and Drawl” explores southern porches and the drawl of a southern accent, which he argues function verbally and visually as distinctive Southern elements echoed in works of art, such as Carrie Mae Weems’s haunting photographs from The Louisiana Project (2003; Jack Sainman Gallery, New York). Painter Fahamu Pecou, in “Soul Food,” describes finding a southern aesthetic in the music of Outkast and Goodie Mob, which influenced works like Hope . . . Maybe, if, or Prob’ly (2013; E. Markwalker, New Orleans, Louisiana). In each essay or vignette, artwork (sometimes by the author and sometimes by other artists) accompanies the prose, creating a cohesive, compelling, and lyrical pairing. While some essays are plainspoken and others poetic, the wide variety of voices demonstrate the complexities of the South and situate the idea of the South somewhere in the middle of the polarized viewpoints commonly held. What Southern Accent ultimately reveals is that the South is not easily categorized.

Southern Accent does not shy away from complex ideas and questions about the region or Southern identity. In so doing, it presents a far wider view into the South, punctures stereotypes, and demonstrates the complexity of place. This catalogue is therefore an important contribution to existing scholarship. Southern Accent is not only a bellwether for new approaches to thinking about the region within the context of contemporary art, but it also provides a framework for considering it through the experiences of its most accomplished voices. In its attempts to decipher misconceptions and untangle truths about the South while still preserving the soul of its subject, Southern Accent does not present a simplistic or cohesive picture of the South; it instead embraces the indefinable aspects of a region that is always in flux and constantly evolving and reinventing itself, notably through its art and visual culture. Southern Accent therefore stands as a testament to this particular place at a very specific moment in time.

Cite this article: Jennifer Jankauskas, review of Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art, edited by Miranda Lash and Trever Schoonmaker, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1649.

PDF: Jankauskas, Southern Accent

Notes

- Edward L. Ayers, “What We Talk about When We Talk about the South,” in All over the Map: Rethinking American Regions, eds. Edward L. Ayers, Patricia Nelson Limerick, Stephen Nissenbaum, and Peter S. Onuf (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 62–82. ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer Jankauskas is Curator of Art at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts