The California Raisin

Consider the humble raisin. In the world of dried fruit, it is usually ranked low in the hierarchy, and yet it occupied a definite niche on American menus and in its visual culture. Few who enjoy these tasty morsels in their Raisin Bran, breakfast muffins, and rum raisin ice cream could explicate from where they originally came or how they came to be so firmly inserted into our diets. Even more intriguing in a world where foodstuffs are increasingly dissociated from their place of origin, why does the raisin continue to be associated with one locale, when they are in fact grown globally, from Chile and Argentina to Turkey? We should ask why when we “think raisins” do we “think California,” as an oft-repeated advertising mantra instructs us?

This essay derives from an exhibition I curated, California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820–1930, for the Laguna Art Museum, part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA (Los Angeles/Latin America) initiative, which explored the art historical trajectory of lands that once were New Spain, then became Mexico, and after 1850, California.1 That story begins in mid-eighteenth century Spain, where King Charles III commanded missionaries to the New World, part of the multiple religious crusades enacted in the Spanish colonies of northern Mexico and southern California. When the friars were not Christianizing the native peoples, they were forcing them to cultivate Hispanic produce. In 1821, after these lands became part of independent Mexico, local people continued to cultivate grapes for wine and also grew Muscat grapes for raisins. After the Mexican-American War, these same lands were transferred to the United States and became California. As the state developed its agriculture in the late nineteenth century, it focused on the same crops—oranges, olives, and grapes—that Franciscan friars imported from Spain, transforming the grapes into wine and raisins. Artists began to create imagery for fine art as well as commercial advertising that conveyed the delectable color, texture, and taste of these edible morsels, while reinforcing their association with the Golden State. This essay will map the trajectory of the raisin, and its plump, formative cousin, the grape, within the history of California, where it became a mainstay of the booming state economy and contributed to its image as the national cornucopia by the twentieth century. The visual culture of the raisin will also be demonstrated to provide a microcosm of the shifting national and cultural identities of California over these 250 years, insisting on its Hispanic roots, bringing issues of ethnicity, gender, and labor to the fore in which this tiny fruit has consistently been implicated.

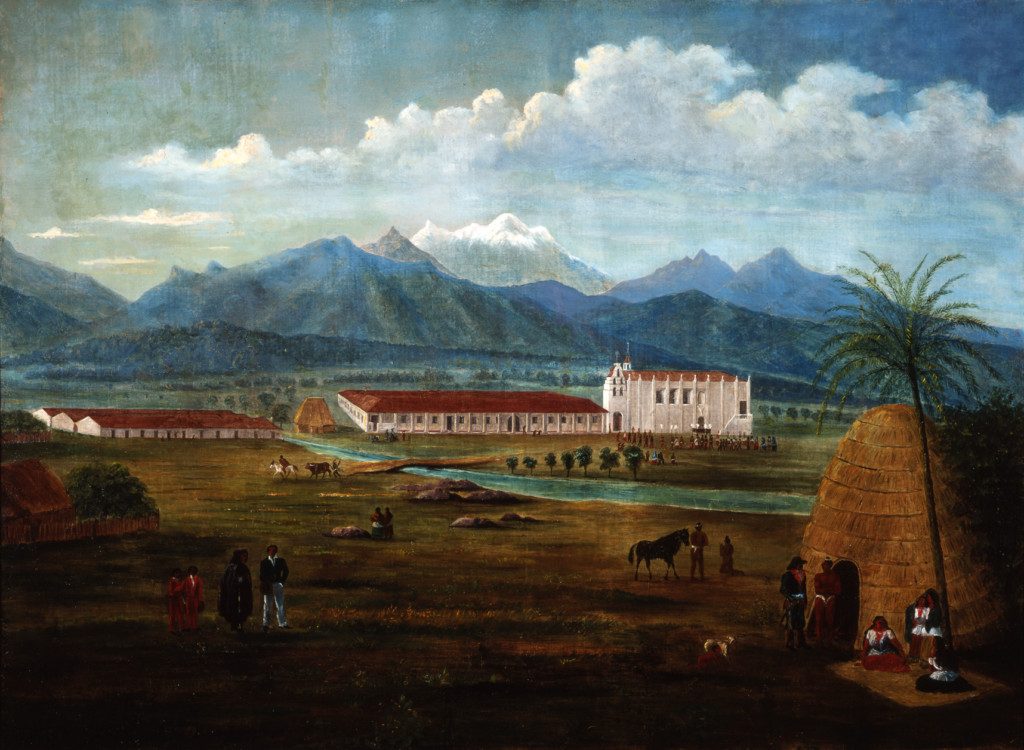

A friar of the Franciscan order, Junípero Serra led efforts to establish a system of twenty-one missions along the California coast. San Gabriel Mission was among them, created in 1771, nine miles east of what is today downtown Los Angeles.2 A rendering of San Gabriel completed by Ferdinand Deppe, circa 1832–35 (fig. 1), is the earliest known oil painting of a California mission. While discussions of mission art usually focus on its church architecture and religious art, attention should be directed toward Deppe’s treatment of the landscape. Agriculture was the principal occupation of the natives, whom the artist is careful to include in the scene. “This included clearing the land, plowing, planting grain and other crops, constructing irrigation ditches, irrigating the soil, cultivating, harvesting and thrashing the wheat and barley, husking the corn, picking the beans, peas, lentils, garbanzos, gathering grapes and other fruits.”3 Mission San Gabriel had the first orange grove in California, planted by the Franciscans from Valencia orange cuttings brought from Spain. It also had olive, Spanish fig, plum, peach, and pomegranate trees, and, significantly, grape vineyards. From the landing of the Spanish missionaries in San Diego in 1769, they brought date palms, Mission figs, and grapes just ripe for drying. Raisins and wine therefore proliferated beginning with the establishment of the mission chain in California. Since the region was semi-arid, an irrigation system had to be devised. The Rio Hondo and several springs fed an aqueduct, reservoirs, and a canal system constructed by Indian labor, visible in the painting. Over its active life San Gabriel was the most productive mission in California, harvesting grains, vegetables, and fruits, some of which are evident in the Deppe rendering. The all-important trade route known as the Old Spanish Trail began near San Gabriel, ensuring that it was not a place of reclusive religious contemplation, but instead was a site where cattle were raised, goods were traded, travelers could get a meal and spend the night, and oranges, olives, and grapes thrived.

Within this Hispanic tradition—which includes California—artists proudly focus on native produce rather than an assortment of foreign and exotic items featured in the art of East Coast painters who followed the Dutch tradition. “Many paintings by Mexican artists reflect the profound connection the people have with their traditional food,” Rita Pomade explains. “In this respect, their work differs markedly from the paintings of the European schools.”4 California is the heir to that Spanish pictorial tradition, as Nancy Moure avers: “Generally, California’s contribution to the American still-life tradition lies in the objects depicted: her own native flora (calla lilies, cacti, dried desert plants, squash), manufactured items associated with the state (rusting farming equipment), and items of Mexican heritage or manufacture.”5 Native plants and foods convey cultural identity as do the modes of pictorial expression utilized to depict those subjects. Analyzing still lifes, market scenes, and landscapes of production reveal a Hispanic tradition formulated in Spain and adapted to conditions in Mexico and then California. This continues in the work of Frank Chamberlin, one of the most influential California painters of the early 1900s, whose classically ordered still life Fruit and Majolica (fig. 2) highlights both green and purple grapes.

By 1861, Governor John Downey wanted to provide the state viticulture with a needed boost. He asked Col. Agoston Haraszthy, a Hungarian immigrant who had settled in Sonoma, to go to Europe and find sample cuttings of the best European varieties of grapes. Called the Father of California Wine, Haraszthy demonstrated perseverance and methodology that revised the ways of the vintners and put the state wine industry on firm footing.6 When the British-born Edwin Deakin arrived in San Francisco around 1869, he focused on regional subjects, first the untamed northern California wilderness. By 1880, he began to create still lifes of hanging grapes whose popularity was linked to the proliferation of the fruit. Flame Tokay Grapes (1884; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) is typical of his treatment, highlighting this single variety against a crumbling mission wall. Such imagery could be read as a celebration of the colonial founding of California by the Spanish friars, who had guided the mission Indians in establishing an organized system of viticulture. By the late nineteenth century, grapes and oranges were well established as the two signature crops of California.

Grapes, crushed and fermented into wine instead of dried into raisins, inspired the enigmatic canvas by Arthur Frank Mathews, The Grape (The Wine Maker) (c. 1906; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco). It presents a seated female figure that is nude except for a red cloth draped over her lower torso, with a suspended bunch of grapes over a large bowl positioned between her outstretched thighs. Her dark hair and skin identify her as Hispanic and reference contemporary anxieties about Mexican and Chinese vineyard workers who—as Shana Klein has discussed—were regarded as inferior to European Americans and therefore a potential source of contamination through their direct contact with these healthy American fruits. 7 Yet the artist creates a deliberately tactile image in which attention is focused on the young woman’s hands squeezing the grapes through her red-stained fingers, which are positioned directly opposite her pudenda. This method of extracting the juice from grapes had in fact been replaced centuries before by the use of wine presses, suggesting that Mathews resorted to such a romanticized conceit to further eroticize his subject. Her solid figure contrasts with the lyrical and even feminized motifs of poppies and laurel or eucalyptus leaves on the frame carved by Mathews’s wife, Lucia—his partner in the Furniture Shop, which promoted the California Decorative Style.8 Visual dynamics seem to reinforce gender dynamics. Licensed by the winemaker’s ethnicity to portray her as sensual, Mathews nonetheless presents her directly engaging the viewer, without shame, in the manner of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes in his Naked Maja (before 1800; Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid). Representing the agricultural trajectory of grapes brought from Spain to their New World missions, he appropriates Spanish artistic models to create an original emblem of California culture.

Returning to the raisin: it is essentially a grape dried in the sun or otherwise dehydrated. In Philadelphia, Raphaelle Peale painted Still Life-Strawberries, Nuts &c. (1822; Art Institute of Chicago) into which he inserted late-season grapes still on their stem drying and transforming into raisins. In the context of his trompe l’oeil compositions, raisins appear as exotic specimens, placed alongside the imported porcelain and glassware. Rubens and Mary Jane Peale created Wedding Cake with Wine, Almonds, and Raisins (1860; Munson- Williams-Proctor Arts Institute), in which the artistically frosted raisin cake appears among the best crystal and china as a delicacy for a very special occasion. In paintings such as La Merienda (The Afternoon Meal) (fig. 3), by contrast, Spaniard Luis Meléndez highlights the delectable color, texture, and taste of fruits that are native to his Iberian peninsula. About 1772, when the artist painted this still life, Spain had commercial relationships with countries from the Middle East to Peru, whose fruits and vegetables were transferred to its fecund soil. Melons, pears, and glistening grapes are all products of the terrain he depicted in the distance.

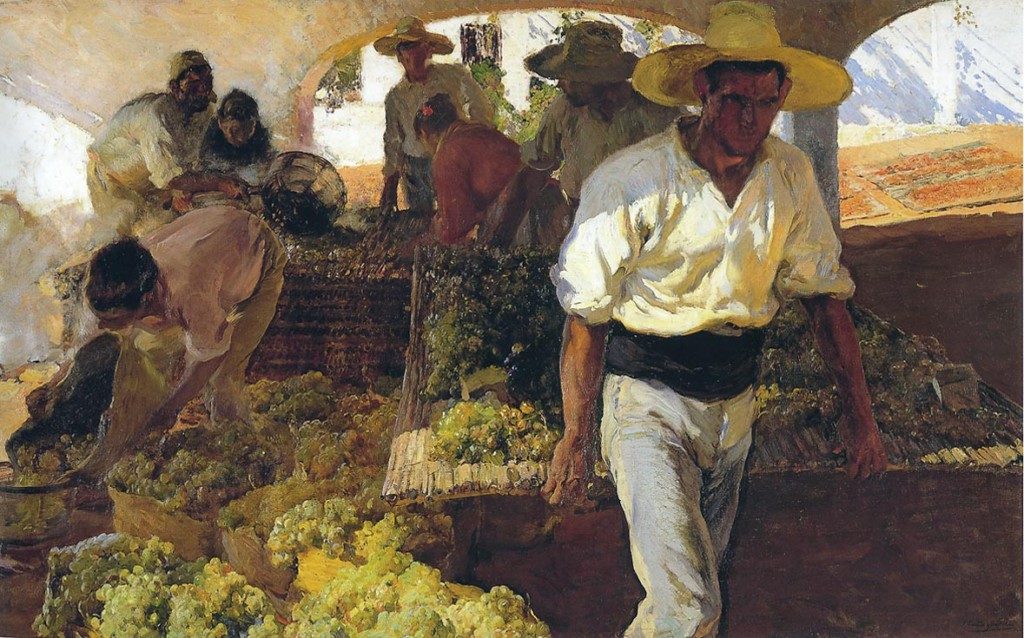

Like Meléndez, Spanish Impressionist Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida created a series of works that featured Muscat raisins: large, oversized, dark, meaty, sweet raisins with a full fruity flavor. His Preparing Raisins of 1900 (fig. 4) highlights a bounty of grapes laid out in baskets before the viewer. Some workers are engaged in moving recently picked fruit into a shaded arcade to await processing, while several others are transporting the ripened grapes on a large rack. But the faces of these men and women remain in shadow, and the grapes take center stage in this large-scale canvas. Painted when industrialization was on the rise, these paintings admit no sign of modern technology but provide a nostalgic look at simpler times when work was done by hand. Although dated circa 1900, these artworks provide a window into the historic past of Spain.

These grapes are objects of pride and are the primary crop of Malaga and of Valencia, Spain, the latter of which was Sorolla’s hometown. However lush and seductive the Muscat grapes appear, the problem was that they had seeds. Extra work was required during processing to remove the seeds by penetrating the skin of the raisin, which caused them to become sticky and clump together in their packaging. In another of Sorolla’s canvases, Stemming Raisins, Javea (1898; private collection), he moved in for a close look at the female forms bent over their workbenches, removing the stems from the fruit. A contemporary observer described the scene that caught the painter’s eye, adding details of the conditions under which these women worked:

A walk through the town [of Javea] will take you past some of the great raisin warehouses. Inside, in the semi-gloom, hundreds of women are stemming raisins for shipment to England. As they work, they sing in honor of the Virgin, a dragging canticle that echoes through the ancient arcades of the place and out into the still afternoon air.9

Packing Raisins, Javea (1901; private collection) shows the final stage of work before the raisins are shipped to market. In these paintings, Sorolla created nostalgic renderings of picturesque interior scenes out of what was actually painstaking and messy labor for these women. When critics characterized his cheerful renderings of workers as simple-minded and condescending, he responded that he was promoting a positive image of Spain among Europeans who considered his country a backwater.10 He intended his visual representations of the processing of grapes to raisins to be nationalistic proclamations. In this impulse, Sorolla found great support from his patron Archer Milton Huntington—son of Arabella Huntington and stepson of railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington—founder of the Hispanic Society of America and a scholar of Hispanic studies. This interest was a direct outgrowth of his upbringing in California, which had been ceded from Mexico to the United States only twenty-two years before his birth. In his home city of San Francisco, he would have daily encountered people speaking Spanish and signs of the art and culture of Spain and Mexico.

Meanwhile, in 1872, the English-born viticulturist William Thompson developed a seedless grape in California, which quickly became the variety of choice for raisin production. Thompson introduced the Sultana grape—the high-yielding, pale-green seedless variety—that followed on the heels of the 1869 completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, insuring speedy delivery of California’s natural bounty around the country. So significant was the contribution that Thompson made to local agribusiness that a California Registered Historic Landmark No. 929 was erected in Sutter, California, to mark the “Site of Propagation of the Thompson Seedless Grape,” with a text explaining the circumstances of this momentous development:

William Thompson, an Englishman, and his family settled here in 1863. In 1872 he sent to New York for three cuttings called Lady de Coverly of which only one survived. The grape, first publicly displayed in Marysville in 1875, became known as Thompson’s seedless grape. Today thousands of acres have been planted in California for the production of raisins, bulk wine and table grapes.11

California was now turning the tables on Spain, usurping its raisin production.12 On an overland journey from Mexico to Southern California in 1882, William Henry Bishop noted: “One of the most important districts for raisin-culture is near Sacramento and Marysville,” where he closely observed their cultivation:

The grapes for raisin-making are of the sweet Muscat variety. There was a “raisin-house” piled full of the flat boxes in which raisins are traditionally packed. The process of raisin-making is very simple. The bunches of grapes are cut from the vines, and laid in trays in the open fields. They are left there, properly turned at intervals, for a matter of a fortnight. There are neither rains nor dews to dampen them and delay the curing. Then they are removed to an airy building known as a “sweat-house,” where they remain possibly a month, till the last vestiges of moisture are gone. Hence they go to be packed and shipped to market.13

His commentary confirms that over the decade of the 1880s, the California agricultural vanguard turned to cultivating citrus and grapes, which in their dried form as raisins became a mainstay of the booming state economy.14

However humble the raisin—peanut-sized, wrinkled, and ruddy purple in color—might appear, the raisin growers became the most powerful agricultural trust in American history: the California Associated Raisin Company, now the Sun-Maid Raisin Growers of California. Between 1912 and 1919, the California Associated Raisin Company developed into what became known as “the raisin trust” by combining principles of nineteenth-century agricultural labor collectives with twentieth-century corporate and legal strategies.15 Innovations in marketing and advertising fostered company growth and its eventual monopoly, and this is where the visual arts became a critical component. In 1915, company officials deputized a battalion of sale agents to hawk what they christened “Sun-Maid” brand raisins directly to grocers in major cities. Until sugar became a staple in the mid-nineteenth century, the raisin was valued as a sweet delicacy, an extravagance for special occasions such as the celebration of a marriage, as it appears in Peale’s Wedding Cake with Wine, Almonds, and Raisins. The goal was to change that perception, and to make raisins a year-around staple and not just a holiday treat.16

In 1915, the logo of the Sun-Maid Girl debuted at the San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Throughout the exposition grounds, a company of young women dubbed the Sun-Maid Girls dressed in white blouses with blue piping and matching blue sunbonnets handed out samples to visitors (the bonnets were later changed to red). Among them was Lorraine Collett, who in her off hours posed in the studio of artist Fanny Scafford for the Sun-Maid logo. Scafford experimented with a variety of poses and props, eventually settling on the now-iconic stance holding an overflowing tray of grapes with a glowing sunburst behind her.17 So while the distinctive Sun-Maid label became a national icon through an extensive advertising campaign in national newspapers and magazines, the San Francisco–based Scafford fell back into obscurity.

In 1925, Norman Rockwell was engaged to create an updated advertising campaign aimed at a middle-class audience in prosperous post–World War I America. Given the artist’s predilection for depicting the homiest Americana, it is not surprising that two works in the series feature grandparents and their grandchildren coming together over foods that feature raisins. More specifically from a marketing point of view, these images underscore the process whereby the older generation—who had long appreciated the digestive properties of raisins and prunes—is passing their taste on to the younger generation. One image features the grandmother pouring raisins directly from the sack into the eager hands of her grandson, while other children look on enviously. The slogan reads “Lucky the sack’s so big!—and such a bargain! For youngsters, too, can tell fine raisins.” Not to be forgotten, the grandfather appears in a second picture sitting at a parlor table enjoying dessert with his young charges, below whom is inscribed: “The more raisins the better the pudding.”18

A more radical painting in the series, Fruit of the Vine, 1926,19 moves away from the predictable trope of doting grandparents to contrast a modern woman and her old-fashioned mother in a Vermeer-like domestic interior. Light entering from a window at left illuminates a well-worn kitchen table flanked by two women, modeled by the artist’s first wife, Irene O’Connor, and her mother. They represent a matronly figure in black with a white collar and apron and her adult daughter clad in stylish dress, necklace, and hat, who has just come from the store. From the brown paper bag on the table she has just removed—with properly gloved hands—a blue box whose contents she has spilled onto the table, to the delight of her mother. Close inspection reveals that it is a box of Sun-Maid raisins, whose blue color referenced its source in what was described on the box as “puffed seeded Muscats” and is repeated in the shade of the costume worn by Irene. The serviceable mixing bowl is at hand, ready to receive the ingredients for the treat her mother is undoubtedly going to prepare.

These oil paintings soon became the basis for advertisements that appeared in many women’s magazines of the day, such as Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal. Now recognized as one of artist’s most successful commercial advertisements, it promoted the raisin by placing it within the context of a typical Rockwell scenario: the comfort of a cozy kitchen and the anticipation of freshly baked cookies that connoted American middle-class family life. The company goal was to make raisins a year-around dietary staple rather than just for special occasions. Part of its successful advertising campaign, Rockwell’s imagery helped to increase nationwide raisin consumption, with the raisin ranked as a major industry in California, second only to citrus. Drawing on Vermeer and other fine art references, Rockwell’s painting-turned-illustration helped to elevate the status of the produce he depicted.

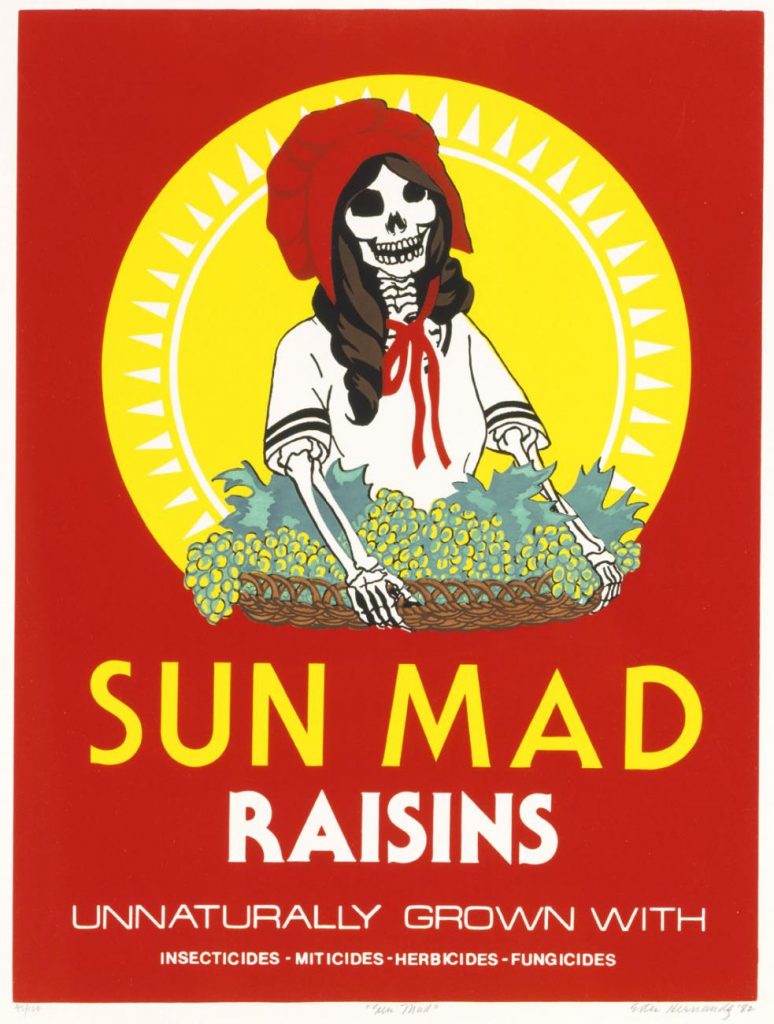

In his 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck narrates the journey of the Joad family from Oklahoma to California, where they seek work as migrant laborers.20 Grapes make their first appearance in the novel in chapter ten, when Grandpa Joad dreams of the abundance of grapevines that exist in California at this juncture—a symbol of the dream of plenty, of a better life. Later, of course, they become a symbol of bitterness as the family faces the loss of dignity and the collapse of their dreams. Coincident with the publication of Steinbeck’s novel, the young César Chávez was first exposed to unions in San Jose, California, where his family was working. By 1965, Chávez—who became head of the United Farm Workers union—was crisscrossing the state, organizing workers, increasing awareness of the dangerous side effects of the agro-industry, and fighting for the cause of farm labor rights. In September, he was in the San Joaquin Valley—raisin country, located in Northern California’s Central Valley, just east of the San Francisco Bay Area—and called for a strike against the grape growers. Here farm laborers and their families lived and unknowingly bathed in and drank polluted water and worked in an environment contaminated by pesticides. Among the activists were members of the Hernández family. Little wonder that when the Chicano movement seized upon the opportunity to use art as a social weapon, artist Ester Hernández recognized an opportunity. Searching for a vehicle to critique the agribusiness at the US-Mexican border, she chose the familiar Sun-Maid box (fig. 5). She transformed the Sun-Maid Girl into a “Sun Mad” figure of death, borrowed from Mexican political cartoonist José Guadalupe Posada. Her text reads: “Unnaturally grown with insecticides, miticides, herbicides-fungicides.” The familiar logo on her poster expresses her concerns and unmasks a more sinister side of large-scale corporate raisin production. Her screenprint became another icon, emblematic of the troubled labor relations in California—with its strong Hispanic presence—a topic that sadly resonates today.21 And so the visual culture of the raisin evolved in yet another stage in its history, addressing issues of cultural identity and shifting political borders in late twentieth-century California Mexicana.

Cite this article: Katherine Manthorne, “The California Raisin” in “The Gustatory Turn in American Art,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 3, no. 2 (Fall 2017), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1606.

PDF: Manthorne, The California Raisin

Notes

- Katherine Manthorne, ed., California Mexicana: Missions to Murals, 1820–1930 (Laguna Art Museum with the University of California Press, 2017). The exhibition was held at the Laguna Art Museum, October 15, 2017 to January 14, 2018. ↵

- It moved three miles to the northwest in 1775. For details of the move, see www.missionscalifornia.com. ↵

- Eugene Sugranes, History of the Mission: San Gabriel 150th Anniversary (San Gabriel: San Gabriel Mission,1921), 36. ↵

- Rita Pomade, “A Feast for the Eye: A Painterly View of Mexican Food,” Arts of Mexico (January 1, 2006), accessed June 5, 2016, http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/1069-a-feast-for-the-eye-a-painterly-view-of-mexican-food. ↵

- Nancy Dustin Wall Moure, California Art: 450 Years of Painting and Other Media (Los Angeles: Dustin Publications, 1998), 285. ↵

- For further background, see Brian McGinty, Strong Wine: The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998). ↵

- See Shana Klein, The Fruits of Empire: Contextualizing Food in Post-Civil War American Art and Culture (forthcoming: University of California Press). ↵

- Eli Wilner, ed. The Gilded Edge: The Art of the Frame (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000), 125. ↵

- William E. B. Starkweather, “Joaquín Sorolla: The Man and his Work,” in Eight Essays on Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, vol. 2 (New York: Hispanic Society of America, 1909), 100. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- For the inscription in the Historical Marker Database, see www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=12008 (accessed February 2, 2017). ↵

- For background and statistics see: Anna L. Palecek, Sun-Maid Growers of California (London: Dorling Kindersley, 2011), esp. 36–39. ↵

- William Henry Bishop, Old Mexico and Her Lost Provinces. A Journey in Mexico, Southern California, and Arizona by Way of Cuba (New York: Harper and Bros., 1883), 342, 397. ↵

- A. J. Winkler, et. al., General Viticulture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 659–60. ↵

- For a detailed discussion of the legal and business aspects, see Victoria A. Saker, “Creating an Agricultural Trust: Law and Cooperation in California, 1898–1922,” Law and History Review 10 (1992): 93–129. ↵

- Anna L. Palecek, Sun-Maid Raisins and Dried Fruit: Serving American Families and the World Since 1912 (London and New York: DK, 2011), 52–53. ↵

- Ibid., 54–55. ↵

- Ibid., 62–63. ↵

- Norman Rockwell, Fruit of the Vine, 1926. Oil on canvas, 31 x 27 in. Sun-Maid Growers of California, on long-term loan to the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass. ↵

- The title is taken from a verse from Julia Ward Howe, The Battle Hymn of the Republic: “Mine eyes have seen the coming of the glory of the Lord, He is trampling on the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” ↵

- See Amalia Mesa-Bains, Ester Hernández (San Francisco: Galería de la Raza, 1988) for further background. ↵

About the Author(s): Katherine Manthorne is Professor of Modern Art of the Americas 1750–1950 at The Graduate Center, City University of New York.