The Language of Line: Chinese Writing, German Speech, and the Visual Poetics of John Winkler’s San Francisco Chinatown Etchings, 1916–1921

John W. Winkler (1894–1979) was born in Vienna and immigrated to the United States as a young man. Arriving in San Francisco in 1912, he studied with the painter and printmaker Frank Van Sloun at the San Francisco Institute of Art, and by the 1920s, he was an internationally celebrated etcher.1 Between 1916 and 1921 Winkler made at least 120 etchings of Chinatown, which was a popular subject among local artists at the time.2 But Winkler’s Chinatown imagery differed from the picturesque representations of his contemporaries; sometime late in 1916, his attention turned from the buildings of Chinatown to people at work in the neighborhood.3 This shift was indicative of the artist’s increasing identification with his fellow workers, immigrants, and ethnic outsiders in San Francisco at the start of World War I. As a German speaker caught up in xenophobic hysteria during the War, Winkler found a metaphor for his struggles in his experiences of Chinatown. Critic Louis Godefroy wrote in 1925 that Winkler’s Chinatown etchings “will remain a vital expression of this paradoxical bringing together of two most opposite races and civilizations.”4 This essay will propose that it was precisely that “bringing together”—in other words, Winkler’s identification with the simultaneous centrality of Chinese Americans within, and their alienation from, the city of San Francisco—that drew him to Chinatown during the First World War.

This text will not be an examination of Chinese experience or of Chinatown as a subject, nor will it suggest that German/Austrian and Chinese immigrant experiences were parallel. Winkler’s engagement with Chinatown was always from a position of relative privilege, and in finding it a useful frame for his experience of cultural and linguistic alienation, he in some ways reinscribed the very racial and ethnic hierarchies by which he was constrained. Nevertheless, in his interpretations of Chinese text and labor through the specifically linear and autographic aesthetic of the Second Etching Revival, Winkler found a productive metaphor for his own racialized identity during the War.

This study will rely on three forms of evidence: close reading, an historicized discussion of medium specificity, and an exploration of the cultural and artistic contexts within which claims about that specificity were being made. This approach, informed by social history methods, recognizes that any interpretation is dependent upon the intersection of broad demographic realities (such as class, race, and gender) and individual bodies of knowledge. Illuminating the changing contours of contemporaneous attitudes about immigrant communities through an examination of language and racial iconographies in this period reveals the unique details of Winkler’s etched images of Chinatown—and offers one explanation of their uniqueness. Indeed, my initial attention to Winkler’s etchings was prompted by my curiosity about the apparent differences between his images of San Francisco Chinatown and those of his contemporaries. Close reading thus became the foundation for a more precise description of those differences: Winkler’s location of himself in relation to the inhabitants of Chinatown, for one, and his unusually accurate and respectful representation of Chinese text, for another. Investigating the connection between these two characteristics, identification and language, led to the discovery that etching in this moment was overwhelmingly described using a vocabulary of line, language, and autograph—in other words, Winkler’s focus on identity and language was in direct dialogue with contemporaneous constructions of the aesthetics of etching itself. Widening the scope to broader cultural conversations about race, ethnicity, and language, it became clear that any engagement with such questions during World War I would have been fraught with nationalist overtones—and productive of significant anxiety among non-native speakers of English. Taking into consideration Winkler’s own speech and writing, the artist’s intense engagement with an unfamiliar linguistic system thus became something more complicated than an interest in the exotic Other. Although Winkler’s biography is a frame for this discussion, his conscious intentions regarding these etchings will not be its focus. No documented claims by Winkler such as those proposed in this text have come to light—and yet the etchings speak for themselves.

Early in his career, Winkler developed an essentially linear style that was conducive to on-the-spot rendering of a scene—a rendering that he made directly on the copper plate.5 Contemporary critics celebrated this plein air method because it entailed drawing directly on the etching plate rather than making pencil or ink sketches that were later translated into etchings. Winkler’s teachers, as well as more broadly influential etchers, consistently advocated working directly on the plate. It was said that Van Sloun, with whom Winkler first studied, always drew directly onto the copper without using preliminary sketches.6 Joseph Pennell, whose visit to San Francisco prompted the formation of the California Society of Etchers in 1912, wrote in his 1926 etching manual, “If a great artist makes a fine sketch on paper, full of vigor and vitality in every line, he cannot copy it without losing all that vitality—he must do it straight on the copper or never do it.”7 In 1921, Howell C. Brown wrote of Winkler: “With plate in hand he draws directly on the spot, even at night.”8 In addition to giving Winkler’s etchings “vitality,” this on-the-spot technique lent his images authenticity and authority; plein air technique transformed his etchings into indices of the city in which he stood.

According to Winkler’s fellow artist Hill Tolerton, working on the spot allowed the artist to capture not just the precise details of a place, but also its emotional valence: “You see not only what he sees,” Tolerton wrote in 1916, “but as he saw it when the mood that suggested the picture was dominant.”9 In both indexical and qualitative terms, Winkler’s etchings made specific claims about the artist’s identity and presence in Chinatown.

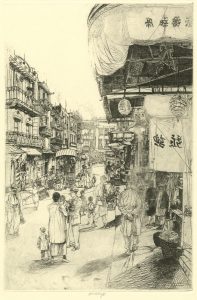

Winkler’s increasing identification with the residents of Chinatown is evident in his etchings from 1916 onward. In Busy Day in Chinatown (c. 1917–20) (fig. 1), for example, the artist himself is evident busily etching the scene in the middle of the plate. Winkler is simultaneously observer and observed in this image, with its paradoxical claims of plein air observation and carefully planned self-portraiture. As a man at work, he is one of many likewise occupied on the street, and at first glance, he blends in seamlessly.10 In an almost unconscious revelation, however, we eventually notice he is the only foreground figure lacking a shadow—an oversight that perhaps reveals the self-portrait to be a later addition to Winkler’s directly observed scene. Thus ungrounded, Winkler is in, but still not quite of, the Chinatown street.

In another print, Winkler’s presence is implied despite his physical absence.

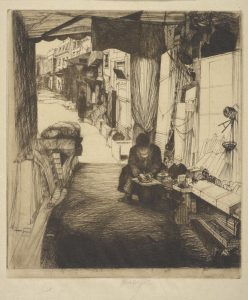

The Delicatessen Maker (new) depicts a Chinese figure working at a table (fig. 2).11 Bending over his work, the figure is analogous to the etcher who bends over a plate, carefully biting the lines of his print (the more so because in the image, the material over which the figure bends is in fact entirely made up of etched lines). Early in his career, Winkler changed his technique: instead of biting the etching plate by immersing it in a bath of acid, he used a brush to apply acid to individual lines, therefore more closely controlling the depth of each stroke. A 1916 photograph of Winker shows his absolute concentration as he engaged in this delicate process, and suggests the phenomenological empathy that Winkler must have felt as he watched the delicatessen maker at work (fig. 3).The title of Winkler’s print underscores the connection between the Chinese and Austrian makers, albeit possibly by accident. By the end of the nineteenth century, the word “delicatessen” was commonly used in American English to refer to finger- and picnic-style foods as well as other well-crafted delicacies; it was also often (although not exclusively) associated with German culture.

Many viewers of The Delicatessen Maker would likely have read it as a straightforward description of the activity depicted, but those sensitive to cultural stereotypes may also have noted the overlap of the American English language, German culture, and the Chinese individual in the print.12

As a depiction of an artist, the Delicatessen Maker has one particularly interesting precedent: a small 1862 etching by Charles-François Daubigny entitled Le Bateau Atelier. Daubigny’s print became familiar to a wider American audience—and especially to etchers—through its publication under the title Voyage en Bateau: Daubigny travaillant dans sa Cabine in Etching and Etchers, a popular manual of technical and artistic instruction (fig. 4).13 Like Winkler’s print, Daubigny’s etching depicts an artist seated in a small interior space, silhouetted against the sunlight coming in from beyond. In both prints, the viewer occupies a deeply recessed position within the room, which in both etchings is similarly filled with shelves, drawers, and various hanging objects. The compositional parallels, from the exaggerated one-point perspective to the emphasis on hatching and crosshatching used to create a sense of spatial depth, reinforce the sense of identification between both prints, and by extension, of Winkler’s identification as an artist with the labor of the Chinese delicatessen maker.

There is a second print entitled The Delicatessen Maker (variant) in which the vantage point has been completely reversed (fig. 5). No longer is there a sense that the viewer is complicit in the scene, as if inside the shop; instead, the perspective is presented from outside on the street, perhaps one more observer in a throng not dissimilar to that in Busy Day in Chinatown. The shift from interior to exterior signals a more significant psychological shift. In the first etching, the artist/onlooker is embedded in Chinatown, privy to its interior spaces and possibly invisible to casual passersby. In this version, the artist/onlooker is as alien to Chinatown as any visitor, part of a heterogeneous mass that moves through Chinatown rather than inhabiting it. It is a reminder of the accidental ambiguity of the shadowless self-portrait in Busy Day in Chinatown.

In the context of Winkler’s broader body of work, these two prints entitled The Delicatessen Maker articulate a troubled identity that can only be explained with the reading of Winkler’s Chinatown etchings through various visual, literary, and historical vectors.

Race and Ethnicity in the Early Twentieth Century

Few people today would describe German national or linguistic identity as a racial identity, but at the beginning of the century that was not the case. Anthropologist Melville Herskovits asked in 1928:

What is a race? It is a question often asked and too readily answered, for we use it with amazing looseness. Not only do we apply it to the larger divisions of mankind, but we also speak of races when we have reference to nations, linguistic stocks, or cultural groups.14

It is clear from Herskovits’s tone that the term “race” was an incredibly flexible signifier in the early twentieth century—even though it was treated as though it had a clear and fixed meaning. The fluidity he points out in the early twentieth-century concept of race presages scholars’ more recent understanding, as anthropologist Audrey Smedley notes, that “‘race’ is nothing more and nothing less than a social invention.”15 Throughout the first part of the twentieth century, race and ethnicity were often used interchangeably. Such blurry definitions transformed “nations, linguistic stocks, [and] cultural groups” into racial categories that asserted alleged biological differences as the bases of, and justification for, segregation.16 Chinese immigrants in San Francisco in the nineteenth century were, by the early twentieth, thoroughly racialized, restricted to particular professions and geographical areas and routinely subjected to violence and legal discrimination. As the United States entered World War I, the country was swept by anti-German hysteria that was similarly racializing. German American communities were seen as racial enclaves, and any characteristics that could be construed as markers of racial difference—significantly including language—became subject to persecution.

Winkler’s efforts to embed himself in Chinatown, and his extended exploration of his status as both insider and outsider in the district, suggest that the artist saw affinities between his experience as a German-speaking American during World War I and the cultural position of Chinese San Franciscans. Using the style, as well as the content, of his etchings to communicate this affinity, Winkler exploited the linear and linguistically coded aesthetics of the Second Etching Revival to nuance his exploration of his position within Chinatown and the United States during the war.

Chinatown as Picturesque Subject

Despite the virulent racism directed at its residents, and despite the persistent perception of the neighborhood as dangerous for non-Chinese visitors, Chinatown had been a popular subject for tourism and picturesque image making since its establishment in the nineteenth century. By 1890, there were more than 30,000 residents in Chinatown, which was located within the twelve-block area bounded by California, Stockton, Broadway, and Kearny streets.17 Visits to the area were often officially discouraged because of the perceived dangers of the neighborhood to outsiders, but that did not actually slow the influx of tourists.18 Historian Raymond Rast has observed that, “A small number of San Franciscans began to suggest that Chinatown’s marginalization allowed its picturesque qualities to flourish. Most who did so were self-styled ‘bohemians’—including the working writers and artists who had founded the city’s Bohemian Club in 1872 and the gentlemen of leisure who later joined them.”19 One of those Bohemian Club members was Winkler’s teacher, Van Sloun.

Whether or not people thought it was safe to visit Chinatown, they agreed on its picturesque qualities. Before the turn of the century, writer Catherine Baldwin wrote of the “irregular and intricate” architecture of the district, admiring its “potted flowers, colorful lanterns and paper globes.”20 Chinatown changed dramatically after the 1906 earthquake and fire, both architecturally and in the administration of its tourist industry. Rast traces the ways in which Chinatown residents—from prominent merchants to everyday citizens—took control of outsiders’ experience. Chinatown’s businessmen created a cleaner, more homogeneous, and safer district that they characterized as “much more beautiful, artistic, and … much more emphatically Oriental,” welcoming tourists to the district by creating an appealingly positive experience of cultural difference.21 Whether tours were run by white guides or locals—and whether individual responses to tourists were intended to be welcoming or hostile—the historian emphasizes that, “both responses reinforced identifications of Chinese San Franciscans as social ‘others’ who stood at odds with a modernizing world.”22 Although to many tourists, the “new” Chinatown seemed less exotically dangerous than the pre-quake neighborhood, artists continued to create images, and interest remained high. Arnold Genthe, for example, published a collection of his Chinatown photographs in 1908 that explicitly took advantage of readers’ curiosity about both the old and new versions of Chinatown.

Winkler refused to be a tourist in Chinatown. The artist moved to San Francisco shortly after the 1906 earthquake and fire. He was immediately enamored of the Chinese American community, which was asserting its right to rebuild in the face of city officials’ efforts to move the Chinese out of the city center. Winkler lived in rooms at the Glencliff Hotel, located on the edge of Chinatown. He also worked in the neighborhood. Art historian Raymond Williams records that, “Upon leaving school he accepted the job of lamplighter in Chinatown, perhaps the one remaining such job in a city illuminated by electricity.”23 Incorporating himself into Chinatown as a worker and proximate resident, rather than as a tourist, Winkler’s decisions—and his images—imply that he saw himself differently from those whose engagement with the district and its people remained superficial. In contrast to the exotic views of Chinatown created by his contemporaries, Winkler focused on everyday street scenes and working people. Contemporary critics hailed Winkler’s Chinatown etchings as valuable historical documents in much the same way that they read Genthe’s photographs of Chinatown taken before and after the 1906 earthquake. If they are instead read as evidence of a sublimated anxiety about language, they remain historical documents—but of a different sort.

In keeping with touristic interpretations of Chinatown as authentically culturally Chinese, contemporary writers described the district as though it was a completely separate city, despite its central location within San Francisco. In 1897, novelist Frank Norris emphasized the invisibility of non-Chinese visitors in Chinatown:

Get down into the very lowest quarter, where the slave-girls are kept, where the Cantonese live, where Chinatown is most Chinese. Of the hundreds of silently shuffling Chinamen, not one will turn to look at you—they will hardly make way for you. You may go into their shops, their tea houses, their restaurants, their clubs, their temples—almost into their very living rooms—to those thousands of slit-like, slanting eyes you do not so much as exist.24

Norris is describing a behavior on the part of Chinatown residents that Rast argues was likely intended as an act of resistance, but as the novelist’s insistent tone of intrigue suggests, it was interpreted as evidence of authenticity: “where Chinatown is most Chinese.” This sense that the Chinese were in the city but not of it was felt as a kind of reversal: white Americans who visited Chinatown discovered that despite being in their native country, they were suddenly alien. Such narratives proliferated well into the twentieth century. In 1917, Overland Monthly contributor Oscar Lewis described the same alienating reversal that Norris had encountered two decades earlier:

Back on Grant Avenue, one notices an occasional Chinaman hurrying by, intent upon his business, and conscious of the fact that he is an alien in a strange land. Once within the limits of Chinatown, however, the tables are turned completely, and it is the native who feels the sense of strangeness.25

Lewis was one among many authors who described this eerie sense of displacement that occurred when one walked three blocks in one direction or the other, to and from Chinatown. Significantly, Chinatown allowed anyone who felt “alien” within its borders to feel American once they retreated. The district thus became a particularly important site for displaced fears of alienation at a period in which national loyalty was of paramount importance. In a city whose population was rich in immigrants and first-generation Americans, one effective strategy for asserting Americanness—and therefore patriotism, in the context of the First World War—was to locate oneself firmly in opposition to a foreign Other. Figuring Chinatown and its residents as inexplicably and inaccessibly foreign, visitors implicitly asserted their own citizenship.

This displaced sense of alienation was expressed as disfigurement and erasure in representations of Chinese people and speech. An example of this can be seen in Arnold Genthe’s 1908 photograph of a man in Chinatown, published in multiple editions of Old Chinatown, by Will Irwin, with the caption, “‘No Likee’: He would notice you no more than a post—unless you pulled a camera on him.”26 In this image, the text representing the speech of the Chinese figure is distorted into dialect, while in the actual image, the figure is hiding his face, an erasure that makes him anonymous, generic, and speechless. Despite this sense of alienation—or, better, because of it—tourists continued to flock to Chinatown throughout the first decades of the twentieth century. As Rast observes, the unfamiliarity of Chinatown allowed visitors to explore and experiment temporarily without censure, a practice that might ultimately “allow visitors to deepen or expand their own identities.”27 Although the argument can be made that Winkler rejected the role of tourist in his extended engagements with Chinatown, he does appear to have used the neighborhood precisely as Rast suggests, as a lens through which to understand his own ethnic experience in the city.

Winkler and the Second Etching Revival

The first Etching Revival was an international printmaking movement in the late nineteenth century whose primary exponents were in France, England, and the United States. Etching societies such as the New York Etchers Club, Boston Etchers Club, and Philadelphia Society of Etchers were all founded between 1875 and 1880, with others following rapidly over the course of the next decade. By 1901, however, Morris T. Everett was writing of etching’s decline in Brush and Pencil, an illustrated fine arts magazine. “The two things primarily responsible for the decline of etching are commercialism and the development of reproductive processes,” he claimed.28 Arguing that the general public was insensitive to the subtleties of the medium and could therefore easily be swayed by inexpensive reproductions rather than original prints, Everett made a fundamentally conservative plea for a second revival of the etching medium. That plea found an eager audience among American artists and collectors, and by the 1910s there was a vigorous community encompassing etching societies across the United States. he Chicago Society of Etchers was founded in 1910 and the California Society of Etchers followed in 1912.

The Second Etching Revival offered Winkler opportunities unavailable to him in other media. Owing to networks created by the earlier generation of etchers, there were national and international exhibitions to which he could submit work by mail at relatively little cost. Moreover, etchings were far more compactly produced and stored than works in other media, such as painting or sculpture. Winkler’s apartment was his studio, and the ability to work in a cramped space was vital for the young working-class artist. The accessibility of etching made the Second Etching Revival a space in the American art world that was particularly welcoming to those marginalized in other contexts; women printmakers abounded, and in stark contrast to those working in other media, they often held leadership positions in professional organizations.29 It is likely that Winkler found in the exhibitions and publications of the Second Etching Revival a national public for a cultural voice that would otherwise have been marginalized.

Everett supported his case for the new revival by quoting a set of aesthetic rules by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the most prominent American etcher of the earlier movement. When a classmate suggested that Winkler would one day surpass Whistler, it was the highest praise the young artist could possibly have received.30 At the heart of Whistler’s dictates were ideas about medium-specificity. “They respected their means of expression,” Everett noted approvingly of the earlier generation of etchers, “and recognized the limitations placed upon the [etching] needle.”31 If a second revival of etching were to succeed, he suggested, “most experts maintain that the highest development of the art is to be reached in perfecting old methods rather than inventing the novelties of an hour.”32 Perhaps because this conservatism was so out of step with the emerging ideologies of modernism (despite their shared language of medium-specificity), the Second Etching Revival has until recently received little attention from scholars beyond the relatively circumscribed world of print collectors and connoisseurs.33 As Winkler’s work makes clear, the specific and intense conversations about the relationship medium, form, and meaning happening within the Second Etching Revival had far-reaching cultural implications.

Critics praised Winkler’s linear style for working in the spirit of the medium, rather than against it. The etching revival of the late nineteenth century had introduced aesthetic debates about the use of plate tone—selective wiping in order to leave films of ink on the surface of the plate—to create dramatic effects. Advocates argued that plate tone was a painterly tool appropriate for fine art printmaking (and indeed, Whistler, that consummate painter-etcher, had, like Rembrandt three centuries earlier, been a master of the manipulation of plate tone). Critics during the Second Etching Revival, however, suggested that plate tone was a way to disguise sloppy technique, and argued that it denied the medium-specific quality of the etched line. Winkler subscribed to the latter position, noting in a disgruntled comment on a print he made while a student at the Institute of Art that it had been his instructor, Pedro J. Lemos, who insisted Winkler use plate tone rather than cleanly wiping his plate.34 His favorable critics agreed with him, and the absence of plate tone became a visual hallmark of the Second Revival.

We can see Winkler’s linear technique clearly in The Delicatessen Maker [Chinatown]. The central figure and the doorway behind him are drawn with densely packed lines and extensive crosshatching. By the Chinese figure, along the front of the store, various shelves and drawers display their contents in intimate detail. In the foreground, however, three buckets are given only the briefest of delineation, and the building surrounding the shop is loosely sketched. The transition from precisely rendered central detail to sketchy marginal indications has several effects: it mimics our natural visual focus, creates an aesthetically pleasing tonal balance, and emphasizes the etching process by which Winkler created the image, from early sketched lines to an increasing, albeit selective, level of finish. Critics understood this sketchy style of rendering, rather than the consistent overall detail of reproductive printmaking, as the sign of true art in etching. John Taylor Arms, Winkler’s champion and close friend, wrote of his young protégé, “When I hear the name John W. Winkler I think instantly of just one thing—a sheer beauty of line quality unsurpassed by that of any other worker in the medium today.” Later in his essay, Arms connects Winkler’s linearity directly to language, asking the reader, “After all, what is the language of a good etching? It is the lines the artist traces through the ground and afterwards ‘bites’ with acid; these are the words by which he expresses himself, the material of which his compositional structure is fabricated.”35 Arms was far from alone in connecting the etched line to the written line and thus to language; indeed, writing became the primary metaphor for drawing at the beginning of the century. Winkler was trained both formally and informally to see slippage between etching and writing. As he struggled with his own language—first in terms of acquiring the practical skills of English speech and spelling, and then during the war, grappling with ethnic prejudice and discrimination—the metaphorical potential of a cityscape filled with calligraphic writing must have struck the artist with some force.

Etching as an Autographic Art

Etching metaphorically became autographic writing at the turn of the century by way of several simultaneous semiotic slides. For instance, equations between etching and ink drawing, and between the drafting pen and the calligraphic pen, coincided with (and were used as explanations for) critical rhetoric that celebrated etchings as expressive of the artist’s hand, in contrast to mechanical printmaking techniques. Diffuse though the genealogical path is, the stage was set in these and related assumptions for a characterization of etching as a form of writing. Critics’ enthusiasm for plein air etching and direct work on the copper plate joined with such ideas to transform the etched image into an autograph—a visually specific instance of writing that signifies identity and authenticity. An autograph, first and foremost, is a word. However, an autograph is a visually distinct and specific word; it is a name, written in a stylized manner by the owner of that name. There is a self-evident difference between an artist’s name that has simply been written out and an artist’s autograph. Whistler’s signature, for example, famously evolved into an entirely wordless butterfly with a scorpion tail—purely visual, it flew through his etchings and insistently extended the margins of their closely trimmed sheets. An autograph is in fact a picture of a word that is itself the privileged sign of the artist. As etching became autographic writing, prints became texts. And although Whistler’s signature butterfly sought to eradicate the written word altogether, we must acknowledge that by absorbing this textual metaphor of autography, etching became haunted by the notion of writing. By fully exploring the autographic metaphor to which he and his contemporaries subscribed, we can likewise begin to understand why writing permeates Winkler’s etchings.

The title of an 1891 volume, The Art of Pen and Ink Drawing, Commonly Called Etching, demonstrates immediately the philosophy of turn-of-the-century artists and art critics regarding the equivalence of etching and drawing in pen.

The Second Etching Revival’s emphasis on the uniquely expressive hand of the artist led critics to characterize etched lines as autographic. Sheldon Cheney, writing in Sunset magazine in 1908, called etching an “autographic art,” a conceit that was ubiquitous in contemporaneous art criticism.39 He explained the term:

Etching is called the autographic art because the artist consummates the whole making of the picture from the conception to the printing of his proofs. There is no middleman, no process engraver, to spread his lines and gray his highlights. … Each indelible stroke of the needle clear and unchangeable in the final print, is an indication of the artist’s temperament, a revelation of his character. The quick nervous motion of one etcher’s hand is as much revealed in the proof as is the firm robust stroke of another, and in each one has the index of the etcher’s being.40

That Winkler and many other artists of the Second Revival lived up to Cheney’s ideal of the etching process is certain, although not all etchers actually printed their own work. Winkler’s contemporary, Roi Partridge, explained why this autographic indexicality was so important: “Nothing in the world is more keenly sensitive to the individual skill or character of the worker than the etched line. Each plate is autobiographic; each print is a paragraph from a man’s history; each line is a thought.”41 Partridge’s metaphor extends the subtle argument of the etched letters on the title page of Etchings of Today, in which drawing and writing were made equivalent. The print becomes a paragraph, and so the image becomes a text. More specifically, it becomes an auto(bio)graphical text in which the artist’s hand reveals authentic identity: a seductive idea for someone like Winkler whose identity was in question during the First World War.

Cheney, Partridge, and others described etchings as autographs—but what of the artist’s actual autograph? In Winkler’s signature, etched into plate after plate, the autograph is a stylized image of a W flanked by horizontal lines. There is an early version of this signature in his 1914 etching, Haunted House (Sally Stanford House) (fig. 7). In this print, Winkler thoroughly and playfully blurs the distinctions between image, text, signature, autograph, and etching. A house on one of San Francisco’s many hills is so brightly illuminated that its various elements are reduced to black lines on the white background, while the night sky is utterly dark. Even in the foreground, crosshatched shadows reach into the lamplit street. A group of cats meanders in single file along the bottom half of the image, moving across the street and along garden walls toward the house. Perhaps they are the ghosts of this “haunted” edifice, trapped as they are in the shadows. Trapped, that is, except for one pale cat, who gazes down at Winkler’s signature in the plate. It is a W formed by straight lines, flanked by two dashes. Hastily scratched and crossing other, descriptive lines, the signature continues the implied line of cats moving from right to left. The crosshatched lines that make up the shadows are like so many more overlapping W’s, and even the legs of striding cats seem to be forming inverted W’s in the street. As a whole, the shadows create a line between light and dark that takes the shape of a sideways W—and the right-hand loop of this W is again bifurcated, creating a W within the W. Like the cats, Winkler’s signature initial haunts the etching, suggesting not only an imaginative slippage between drawn line and written line, etching and naming, but also the uncanny character of Winkler’s identification with the city itself.

American Anxiety About Correct Speech

Etchers were transforming images into autographic and autobiographical writing in the context of a broader cultural anxiety about language in the first decades of the twentieth century. Speech in particular was understood to be a performance of identity and allegiances. Particularly in California, filled with immigrants and aspiring actors, speech was a focal point for self-conscious anxiety in this period, and that anxiety was reflected in contemporaneous advertising. The same issue of Sunset magazine in which Sheldon Cheney argued for autographic etchings featured a cornucopia of advertisements inviting readers to consider their speech and its flaws. For instance: “Do You Stammer?” If the answer was yes, the Pacific School for Stammerers offered potential customers a positive cure: “NO CURE, NO PAY.” “Why go through life,” it queried rhetorically, “with halting tongue?” Directly beneath this copy is another advertisement, this one for the Dobinson School of Expression, in Los Angeles. The Dobinson School, “a school of results,” offers more cursorily to aid in improving one’s “speaking voice, literature, and interpretation.” Further on down the page, in the second column, we are presented with notices for the Jenne Morrow Long College of Voice and Dramatic Action and the Paul Gerson Dramatic School, both of San Francisco. The latter school claims to be the “largest training school of acting in America,” while the former offers the opportunity for “public performances monthly.” These two advertisements are placed below that of the Irving Institute, which offers classes in elocution as a staple of its curriculum. The advertisements for acting schools are clearly aimed at the performance and entertainment industry, which had a significant presence in the San Francisco Bay Area at the time. Juxtaposed with the notice for the Pacific School for Stammerers and the Irving Institute; it nonetheless becomes clear that attitudes toward the spoken word at the beginning of the twentieth century were far more troubled than they first seem. All disordered language, these ads collectively announce, must and would be corrected—at least according to the Pacific School, which proudly declared: “the younger the easier, but young or old, we can CURE all cases.”42

Anxiety about correct speech was nothing new to the United States in 1908. Gavin Jones, in his discussion of dialect literature in Strange Talk: The Politics of Dialect Literature in Gilded Age America, suggests that the debate over language at the turn of the century “was dominated by the concern that the meaning of national identity was culturally shifting, away from its familiar Anglo-Saxon traditions.”43 “For many nineteenth-century Americans,” writes Jones, “the distinct English of French, German, or Spanish speakers represented forms of ‘broken English’ that needed correction.”44 In the early twentieth century United States, foreign words became foreign persons, described and condemned using the language of citizenship and patriotism. As Winkler worked in Chinatown, making prints that insistently documented both Chinese and American text in a medium that was itself coded as language and writing, his audience was likely making parallels between the words and figures in the prints and wondering about the national allegiances of both. In his Delicatessen Maker etchings, as is evident, Winkler’s choice of title was itself an example of an immigrant word that had been, in the words of turn-of-the-century writer and educator Brander Matthews, “naturalize[d].”45

In The Delicatessen Maker (variant), Winkler’s line becomes a versatile tool equally adept at rendering scene, signature, and text. In this scene, all three emphasize the linearity of the medium—sometimes at the expense of legibility. We have seen how this is done in the rendering of the scene as a whole; in addition, Winkler presents text in three forms: Chinese text, English text, and his signature. Chinese characters appear on the bucket that the figure uses as a table support. English writing appears above the storefront, partially obscured so that all we can read are the letters NDO. Finally, Winkler’s signature, the familiar W with a horizontal line on either side, appears in the lower right, its left arm extending exuberantly into the composition in a way that emphasizes its visual and compositional role, rather than its linguistic signification. Text and image, in this print, are equally linear—but while the linearity of the Chinese text underscores its potential legibility (to a Chinese-reading audience46), the erasure and sublimation of English text into image confounds legibility. Winkler was no more able to read the Chinese text than the majority of his collectors were—but his reversal of linguistic privilege in his images pushes back against patriotic demands for unilingualism.

Anxiety about speech and language increased as the twentieth century progressed. In 1917, the Paul Gerson Dramatic School was still advertising; indeed, it had increased in stature enough to move from a tiny advertisement in Sunset magazine to a quarter-page announcement that appeared in each issue of the Overland Monthly, another prominent and popular lifestyle magazine in California. Despite having an increased amount of space in which to advertise, and unlike the ads with which it shared a page, the Gerson School chose not to include any graphics in its advertisement: not even a horizontal rule invades its pure textuality. At the same time, the equally unique sans serif font dramatizes—in an entirely visual and peculiarly linear way—the clarity of elocution promised by the school.47 This focus on linearity as an augmentation of the visual efficacy of language is reminiscent of critics’ celebration of the legibility of Winkler’s line. Where the Gerson School advertisement emphasized the linearity of clear language, Winkler’s prints exploited the linguistic echoes of the etched line. But where the former aimed to improve the intelligibility of American English words, Winkler’s prints delighted in their obfuscation. Continually blurring and erasing English words in etchings that were otherwise celebrated for their accuracy and detail, Winkler used words as metaphors for his own linguistic-ethnic experience. Increasingly surrounded by racist persecution of German speakers and publications, Winkler may well have found the subversiveness of such erasure increasingly satisfying.

Anti-German Sentiment During World War I

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. In February of that year, the German Savings and Loan Society stopped running advertisements in the Overland Monthly. Their January notice, filling the quarter of a page above the advertisement for the Paul Gerson Dramatic School, listed their assets as of June 30th, 1916. Financially, the institution was sound. Why, then, did its advertisements disappear? The answer is not hard to deduce; as the United States entered World War I, anti-German feelings were running high throughout the country. Whereas at the turn of the century, “good will generally prevailed among San Francisco’s European immigrant groups,”48 the War transformed Germans and German speakers into enemy aliens overnight.

Significantly, the hostility directed toward Germans during World War I largely manifested itself as hostility toward the German language. The German population in America was quite large (eight million in 1910), and relatively easy to target because of the high visibility of the German language in the press, in schools, and in community organizations.49 According to historian Benjamin Paul Hegi, “German-Americans believed that the effort to ban German was not simply another attempt at trimming back their culture; rather, it was an attack upon the essence of German culture and what it meant to be German-American.”50 Indeed, legislatures around the country acknowledged this attack, and embraced it. The Nebraska State Council of Defense, for example, prohibited the use of German on the grounds that it “had been a potent preventative means against the Americanization of the people who came under such influence.”51 German Americans seeking to demonstrate their loyalty, patriotism, and Americanness began to introduce English into church services and Sunday schools, voluntarily displacing their own language.52

The German language press was one of the most serious linguistic casualties. In 1910 there were 554 German newspapers and periodicals in the United States. By 1920, the national circulation of German language dailies had dropped by two-thirds, and only half of the publications had survived.53 A contemporary Californian definition of loyalty and patriotism aimed at the German American community suggested that, “One-hundred percent Americans did not insist on using the German language, reading German-language newspapers, or supporting societies that perpetuated alien cultures.”54 The German Demokrat, a daily newspaper from San Francisco, attempted to keep publishing even after the War started. However, the pressure on individual members of the German community was too great, and they canceled their subscriptions.55

By 1917, hundreds of streets, towns, and businesses had been renamed to eliminate references to German history and culture. Such name changes went all the way to the individual level, and had a long history; like many immigrants to the United States, Winkler changed his name from an Austrian form into the Anglicized version of the name we know him by today. Although Winkler’s name change was not a direct response to anti-German sentiment during the war, it reflected some of the same assumptions about naming and assimilation that were at the root of wartime xenophobia. Name changing by immigrants was not uncommon, and those who did not voluntarily change their names at the turn of the century often had them changed by others. In the case of the inhabitants of San Francisco’s Chinatown, whose Chinese names eluded many white American ears, persons would routinely be addressed with generic English names by tourists, writers, and other casual visitors. In Josephine Clifford’s 1880 account of a Chinatown tour, for example, fully four separate Chinese individuals are addressed as “John.” It may well not have escaped Winkler’s attention—and it certainly should not escape ours—that the generic name for Chinese Americans, given by whites, was “John,” the same name that Winkler had chosen for himself when Anglicizing his own name. Although he could not have known it at the time, that choice ultimately connected Winkler yet again, via the specific language of naming, to the residents of Chinatown.

Anti-German rhetoric was not limited to German speakers from Germany; Austrian and Hungarian residents of the United States were also targeted. In a particularly vicious attack on Austria, commentator Charles Pergler wrote in 1918: “There is no Austrian language, no Austrian literature, no Austrian nationality, no Austrian civilization.” Pergler’s point of view was that Austria was essentially a German territory hiding behind a “geographical expression,” and that therefore it, and its subjects, should be treated with as much hostility as Germany itself.56 Winkler, as an Austrian whose spoken and written languages were at best a heavily-accented English, and often a mixture of English and German, would have been a likely target for anti-German propaganda, and possibly even violence, in the United States in 1917. His biographer, Mary Millman, has discussed Winkler’s reaction to the entrance of the United States into World War I in terms of his enthusiastic patriation and American sympathy: “By now thoroughly American in sentiment and allegiance, Winks was the 331st person to register at his local draft board on Sansome Street, and for a time he was eager to be called, imagining the war as another grand adventure.”57 Likely this enthusiasm was also sparked, at least in part, by Winkler’s desire to express his patriotism as unequivocally as possible to the press, as well as local organizations and government officials.58

The threat to German Americans who refused to bow to the demands of American patriotism was very real. 6,300 Germans were arrested during the war under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. Of those arrested, 2,300 were interned by military authorities in three camps located in Utah and Georgia.59 The question of language was at the heart of the camps’ existence. Inside Fort Oglethorpe, the largest of the three facilities, inmates used language to recreate the camp as a space in which, by a stroke of fate, world-class musicians, scientists, and writers were thrust together with merchant seamen and working class laborers.60 The inmates subversively renamed the camp Orgelsdorf and complained about its classist living arrangements, whereby the inmates considered “too influential or knowledgeable to be at large” were kept in catered, relatively spacious rooms that were designated A, while the rest of the camp lived in unsanitary group housing (B) with no plumbing and barely adequate food. Their complaint was issued in the form of a mixed-language slogan published in the camp magazine, the Orgelsdorfer: “In B lebd nur das Herdenfieh / In A die Creme von Germany.”61 The hybridity of this language demonstrates the vacillating power relations between the internees and their captors. To be an effective tool of protest, the American camp officials had to understand the entire slogan, despite the language barrier, and to be a politically meaningful act of resistance, the campers had to use German to argue for the unity of the camp residents in the face of their American captors. The pidgin dialect of the campers, who were safely contained, combined English and German, and became an important symbol of their independence, if not their freedom. For Winkler, on the streets of San Francisco, the same dialect remained a burden. In turning to Chinatown just as American attention to the First World War intensified, Winkler may have been seeking respite. Just as white Americans were often unable to hear the subtleties of Chinese names and other words, Chinese speakers were less likely to hear—and therefore less likely to discriminate against—Winkler’s German accent. Creating autographic etchings in which Chinese and English words commingled, and in which the former had more clarity and prominence than the latter, Winkler was more subtly participating in the kind of hybrid linguistic signification that empowered the inmates of Fort Oglethorpe.

Winkler’s Speech

Evidence of Winkler’s spoken and written language has survived in several forms. His most common written language throughout his life in the United States was a mixture of German and English, and he spoke with a heavy Austrian accent. That he was cognizant that his accent might be an impediment is certain, particularly during his early years in San Francisco. Millman describes his early war experience:

By 1917 the European war had invaded everyone’s daily consciousness, casting long shadows of fear and suspicion across American society. Considering the high pitch of anti-German hysteria then sweeping the West Coast, one wonders if Winks’ practice of pinning lists of English words to a clothesline strung up in his room at the Glencliff was motivated by a desire to subdue his telltale accent.62

Winkler’s desire to speak English was clearly strong, particularly during World War I. The image of Winkler’s room strung with words written out on pieces of paper is striking for its reminder that for Winkler, language was as visual as it was auditory. The sheets of paper, hanging on a clothesline in much the same way that newly printed etchings dry on a rack, also call to mind Winkler’s new-found career as a printmaker. A similarly visual manifestation of Winkler’s anxiety about speech occurs in an undated pen-and-ink self-portrait, in which his mouth is obsessively overdrawn to the point of eradication (fig. 8).

Winkler’s accented speech was reflected in his written English, which freely incorporated German fragments. For example, when later in his career he made a series of wooden boxes with inscriptions, the texts read as immigrant pastiche—dialect, in fact. “‘Dachshund, Pipe / A Krügel Beer / Alte come and light sie mir’,” accompanied a painted self-portrait of Winkler calling his dog to his side; and “Still wiser would / They’ve been theese blokes / Could they have passed / Around some smokes” reveals what the artist’s friend Dave Bohn described as Winkler’s “vintage” spelling.63 The artist’s letters and inscriptions on etchings reveal similar irregularities of language.

Winkler’s use of a mixture of English and German is particularly visual in part because of the unique orthography, which does not alter the way one would pronounce the word, but does disruptively change the way it looks. As in most dialect literature, the spelling of words becomes of paramount importance as soon as they are written down. Written words are inherently visual as well as linguistic objects, a self-evident truth that is illustrated by the importance that typography and its manuscript equivalents have played throughout the history of written languages. Dialect spelling further alienates ethnic speech from its surrounding normative text, reinforcing the visual nature of all text. Spelling becomes the visual analogue of aural disruption, distorting the shapes of familiar words in order to underscore the ethnic difference of the speaker (think of Genthe’s caption, “No Likee,” in which the extra e makes the familiar word visually strange). Josephine Clifford, writing about her tour of San Francisco’s Chinatown, uses her own disregard for the correct spelling of Chinese words to reveal her unconcern for their speech: “[There was] another bowl still smaller, containing a liquor made of rice, in China called Sham-Shoo. (The orthography may not be quite correct; my Chinese dictionary is loaned out.)”64 Calling attention simultaneously to the importance of spelling and her inability to render it correctly, Clifford’s disingenuous parenthetical explanation is a reminder of the alien orthography and alphabet of the Chinese language. After all, any Anglicized rendering of a Chinese word must by definition be only an approximation of “correctness” that relies upon an imperfect system of transliteration.

The inability of tourists to comprehend Chinatown—and, specifically, the Chinese language—was noted indirectly by Clifford, who recounted the “contemptuous” reaction of her companion when she declared her intention to write about their tour of the area: “I speak five [languages],” the friend exclaimed, “but I should never attempt to describe Chinatown till I had learned a sixth—the Chinese.”65In addition to expressing a strong sense of Chinatown’s foreignness, Clifford’s friend echoed the widely-held opinion that language is the key to a culture’s character. Indeed, Chinese residents consciously manipulated language to reinforce the sense of cultural destabilization experienced by tourists. As Rast has noted, “A number of merchants [known] to be fluent in standard English responded in kind whenever tourists tried to barter with them in pidgin.”66 Again foreigners targeted by racist policies and attitudes were exploiting their superior linguistic knowledge as a form of resistance—just as camp members did in the Orgelsdorfer. Scholars have noted that colonial powers used the manipulation and policing of language to lay claim to authority, but such manipulations were also used by those being subjugated to make an opposing claim to independence.67

Intriguingly, in choosing to flank his signature W with two dashes, Winkler was inadvertently referencing a popular point of contention in conversations about patriotism and national allegiance during the war. “German-Americans” during the First World War were targeted for what mainstream commentators described as “the hyphen.” Anti-German groups focused on the hyphen in “German-American” as the root of German-Americans’ lack of patriotism. As scholars Mark Ellis and Panikos Panayi phrased it, “German-Americans were made to recognize the disadvantages of being ‘hyphenated.’”68 In 1918, an Ohio newspaper editor responded to a correspondent defending his identity as a “German-American”:

In the first place, you are not a German-American. You are either an American or a German. The hyphen was shot out of existence the day we severed diplomatic relations with Germany. . . . We have a supreme contempt in this country for the fellow who holds Germany in one hand and the United States in the other with his heart representing the hyphen.69

It is evident from this response that the hyphen had become a visual symbol for German American disloyalty. Although the hyphen is a linguistic sign, it is not a part of language that is audible; it is a punctuation mark, a symbol on the threshold between vision and speech. In fact, in the end, the hyphen is simply a line. By making the problem of German Americans visual rather than linguistic, attacks on the hyphen as a metaphor for split allegiance implicitly argued that disloyalty could be eradicated through the eradication of linguistically inflected line. Winkler’s etchings, in contrast, are an overt and overdetermined celebration of line as personally expressive form: what we might call an extended act of hyphenation through which the artist expresses his ambivalence about the ethnic language with which he surrounded himself—and by extension, about his own identity. Seen in this light, Winkler’s linear etching style was potentially as racially subversive as his German-inflected speech during the First World War.

Chinese Writing in Winkler’s Etchings

Representations of dialect distorted the speech of ethnic others in order to make claims about the Americanness of standard orthography and grammar. Winkler reversed this practice, repeatedly distorting English speech/writing while taking care to render unfamiliar language as accurately as possible. Returning to Busy Day in Chinatown, an almost overwhelming number of Chinese words appear on a multitude of surfaces. Most of the characters, due to Winkler’s keen observation while at the scene, are reasonable reproductions of the original Chinese. Winkler did not speak or write Chinese, and so he could not read most of what he was seeing. It is likely for this reason that they appear backwards in the print, since he etched them directly onto the copper plate as he saw them. (The printing process offsets the image, reversing it on the paper; the same effect in some of his English words is apparent when Winkler forgot to etch them in reverse.) His precision is in stark contrast to the rather haphazard representations of Chinese and Chinese-style writing that dominated popular and commercial visual culture. What is evident from this plethora of Chinese writing is the interest it held for Winkler: a fascination perhaps initially engendered by the aesthetic richness it offered a medium dominated by line.

Chinese characters appear in all of his etchings of Chinatown, sometimes in unlikely places. The only calligraphy in The Delicatessen Maker (variant) is on the bucket in the foreground; the unexpectedness of this detail suggests that Winkler felt that the presence of Chinese text was vital for a successful reading of his etching. Chinese text is equally unexpectedly—and yet insistently—located in The Delicatessen Maker (new). There is no writing within the space of the shop, but there is a series of characters on a door facing onto the street in the background. Not present in early states of the print, this writing was apparently added by Winkler in the studio, where he did not have a model from which to work (the characters, upon close inspection, are clearly made up). Far from negating Winkler’s investment in Chinese language, these invented characters indicate the extent to which Winkler felt compelled to include Chinese text even when it was not actually present in the scene he was drawing. Moreover, even when he invented the individual forms, Winkler was careful to render Chinese text independent, complete, and unmediated by acts of translation. The opposite was overwhelmingly true in American visual culture more broadly, and Winkler’s insistent allusions to Chinese writing were created in direct opposition to writers and illustrators who used mediated and manipulated Chinese calligraphy as an exotic metaphor for broader anxieties about racial legibility and containment. Strikingly, in Winkler’s prints, the opposite transformation occurs again and again: Chinese characters and linguistic/visual systems are privileged while English text is obscured and deformed.

In The Delicatessen Maker (new), Winkler etched the title of the work into the image and then eradicated it. The print contains the title on the plate in the lower right. Winkler has etched dark shadows over the entire bottom portion of the plate, and these heavily bitten lines obscure the title, to the point where the viewer can only make out the last word, “maker,” with any certainty. The letters are at rakish angles, and vacillate between seeming to be all capital letters and a mixture of uppercase and lowercase. It is as though Winkler etched in the title and then forgot that it was there; the title has literally been scribbled out.70 The etching has forgotten its name; or rather, its name has been erased, removed violently by the scratching action of the needle.

Erasure in The Delicatessen Maker (new) is performative in the sense that the trace of its occurrence is apparent. The title of the work is not absent; it was not polished out of the plate and then the plate reworked. Winkler reinscribed the title as mere lines among other lines rather than as distinct letters and words, creating a palimpsest that simultaneously reinforces the distinctness of title from image-making lines, and blurs those two together. In Winkler’s etching, rewriting translates words into image.This translation happens against the grain. Our eyes want to read the original words, and the letters contain strokes that literally run perpendicular to the lines Winkler draws over them to create shadow. Stifling linguistic expression while at the same time making the print more visually effective, Winkler’s palimpsest suggests many of the same conflicts as the visualizations of dialect then produced by his contemporaries.

This performative erasure occurs repeatedly in Winkler’s prints, always fragmenting English words and letters. Recall that in the outside version of the Delicatessen Maker, the partial word, NDO appears at upper left. Similarly, in Corner Fruit Stand with Hydrant, of 1921, the enigmatic letters MURAD appear on a sign board at the upper right, above other, even less legible letters (fig. 9). A later state of the same print repeats the first fragment but replaces the lower one with yet another illegible English word; at the same time, Winkler radically increases the amount of Chinese text present in the foreground of the scene. It is as though Winkler wants to emphasize the irrelevance of English signifiers in Chinatown—even as Chinese text proliferates. In both states of Corner Fruit Stand, Chinese characters are visible on boxes, signs, bottles and jars, door frames, awnings, lanterns, buckets, windows, barrels, and wall hangings. In a moment of playfulness, Winkler presents us with a view into an interior, through a window whose frame becomes the edge of a screen or scroll. Inside, elements of traditional painting—flowers, calligraphy, and cartouches that recall collectors’ seals—hover between representation of reality and the mise en abyme of a picture within the picture. Winkler’s picture within a picture is offered on its own terms, without mediation or comment, for viewers either to recognize or pass by.

Conclusion

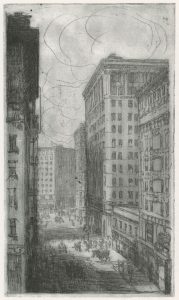

The proliferation of contrasting legibility between Chinese, English, and the autographic line in Winkler’s etchings ultimately becomes its own expressive dialect. Fellow artist Jean Charlot wrote of Winkler’s etchings: “[They] are beautiful for what they say and for what they omit.”71 Charlot was talking about the artist’s sketchy, autographic style, but this metaphorical reading can be pushed a step further. The more closely we scrutinize Winkler’s forms, trying to pin them down one way or another, the more they confound such straightforward readings. Is that a piece of furniture, or a piece of writing? Pulling back from the mise en abyme in Corner Fruit Stand to regain the clarity of distance, we might notice that the roof above the window is itself sketchily marked with lines that hover between tiles and calligraphy. Ultimately, Chinese characters seem to come loose from signs, boxes, and windows to inhabit the very fabric of the city itself. As in Haunted House, the conflation of writing and drawing via this calligraphic line extended beyond Winkler’s etchings of Chinatown. In a 1914 etching of Post Street, clouds, people, and buildings are inexorably transformed into tall scrolls covered in Chinese script (fig. 10). Like the cartouches in the window of Corner Fruit Stand, the print becomes a surface for writing that cannot be read except as metaphor. Winkler’s etchings are haunted by this writing, and they haunt his viewers with it.

The confusion between the visual and textual qualities of the Chinese characters and other lines in Winkler’s etchings paralleled the slippage between text and image that artists and critics found in the medium itself, and it allowed Winkler to sublimate his anxiety about language as an ethnic marker in a visual field. Seeing his own experience mirrored in those of his subjects, Winkler approached Chinatown not as an exotic site of difference, as did so many of his contemporaries, but as a metaphor for his own racialization. Rather than subsuming Winkler’s work into the broad category of Orientalist representations of alterity, we must acknowledge that his work argues for an interracial affinity that complicates existing understandings of race relations in early twentieth-century San Francisco. I hope, moreover, that this study also points toward the broader potential for intersectional histories of race and representation in American art history.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Betsy Fryberger, Alex Nemerov, Jennifer Borland, Hsuan Tsen, and Jennifer Marshall for their significant contributions to this manuscript as readers and respondents. Their thoughtful feedback has immeasurably improved the text, clarifying both my thinking on the subject and the way in which I express those thoughts on paper.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1500

Notes

- For the details of Winkler’s biography, an important source is the excellent and thoroughly researched monograph, Mary Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler—American Etcher (Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1994). ↵

- The canonical source on San Francisco Chinatown as subject is Anthony Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). ↵

- Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler, 61. ↵

- Louis Godefroy, “John W. Winkler, Peintre-Graveur,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 11, no. 4 (April 1925): 227. A translation of the French: “Son oeuvre restera comme une vivante expression de ce paradoxal rapprochement de deux races et de deux civilizations les plus opposes.” ↵

- One result of this was that Winkler’s etchings are generally small, his plates rarely larger than 8 by 10 inches. ↵

- John M. Desgrey, “Frank Van Sloun: California’s Master of the Monotype and the Etching,” California Historical Quarterly 54, no. 4 (1975): 346. ↵

- Joseph Pennell, Etchers and Etching: Chapters in the History of Art, Together with Technical Explanations of Modern Artistic Methods (1941; reprint, New York: Macmillan, 1926), 19. ↵

- Howell C. Brown, “John W. Winkler: An Appreciation,” The American Magazine of Art 12, no. 6 (1921):190. ↵

- Hill Tolerton, “Etching and Etchers,” in Art in California (1916; reprint, Irvine, CA: Westphal Publishing, 1988),121. ↵

- The extent to which Winkler embeds himself in the scene is even more striking when his etching is seen in comparison to Arnold Genthe’s self-portrait, An Unsuspecting Victim, published in Pictures of Old Chinatown (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1908) in 1908 but probably taken a decade earlier. Genthe used various printing techniques to emphasize and isolate himself within the frame; in a print in the collection of the George Eastman House, (Rochester, New York), the photographer even apparently dodged the area around his face, creating a halo-like highlight around his head. Despite his similar pose in Busy Day, Winkler’s self-effacing presentation could not be more opposite to Genthe’s. ↵

- It is important to note that Winkler returned to this plate, and this composition, multiple times over the course of his career. Multiple states exist, and they are not reliably dated apart from the original composition in 1917. ↵

- The Oxford English Dictionary notes that this use of the word “delicatessen” is American in origin, despite the German/Dutch etymology of the word itself. We can assume, therefore, that Winkler was titling this etching, as he did all his prints, in English. ↵

- Philip Gilbert Hamerton, Etching and Etchers (London: Macmillan, 1868). ↵

- Melville J. Herskovits, The American Negro: A Study in Racial Crossing (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), 67. ↵

- Audrey Smedley, “’Race’ and the Construction of Human Identity,” American Anthropologist 100, no. 3 (September 1998): 698. ↵

- This process could be used a form of community building as well as a basis for discrimination—but the logic of race remains fundamentally essentialist regardless of the use to which it is put. ↵

- Raymond W. Rast, “The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco’s Chinatown, 1882–1917,” Pacific Historical Review 76, no. 1 (February 2007): 34. Over time the exact boundaries of San Francisco’s Chinatown have changed, both legally and culturally. ↵

- Ironically, violence was at least as likely to be directed against Chinese Americans by white San Franciscans, especially if they went beyond Chinatown’s borders. See Robert W. Cherny, “Patterns of Toleration and Discrimination in San Francisco: The Civil War to World War I,” California History 73, no. 2 (Summer 1994): 131–32. ↵

- Rast, “The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” 38. ↵

- Ibid., 39. ↵

- Look Tin Eli, “Our New Oriental City—Veritable Fairy Palaces Filled with the Choicest Treasures of the Orient,” in San Francisco: The Metropolis of the West (San Francisco, 1910), quoted in Rast, “The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” 54. ↵

- Rast, “The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” 33. ↵

- Raymond Wilson, “Etching in America’s Far West,” Print Quarterly 2, no. 3 (September 1985): 204. ↵

- Frank Norris, “Cosmopolitan San Francisco; an Article Reprinted from The Wave of Dec. 24, 1897” in Frank Norris of “The Wave”; Stories and Sketches from the San Francisco Weekly, 1893 to 1897 (San Francisco: The Westgate Press, 1931), 141. ↵

- Oscar Lewis, “A Transplanted section of the Orient,” Overland Monthly 70 (July 1917): 25. ↵

- The same image was published with different captions between 1908 and 1913. The alternate caption read, “No Faces!” and used “No Likee!” for a second photograph of a child hiding his face from the camera. For the two versions, see Will Irwin and Arnold Genthe, Pictures of Old Chinatown (New York: Moffatt, Yard, 1909) and Will Irwin, Old Chinatown (New York: M. Kennerly, 1913). ↵

- Rast, “The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” 39. ↵

- Morris T. Everett, “Revival of Interest in Etching,” Brush and Pencil 8, no. 5 (August 1901): 234. ↵

- Bertha Jaques, for many years Secretary of the Chicago Society of Etchers, is probably the most well-known example, but even in the first Etching Revival of the late nineteenth century, women were so ubiquitous that curator Sylvester Rosa Koehler, of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, could write, “An exhibition made up entirely of the work of women needs hardly to be introduced today with words of excuse or explanation. … Never before and nowhere else has etching been practiced by female hands as enthusiastically and as assiduously as in America.” See Sylvester Rosa Koehler, Exhibition of the Work of Women Etchers of America (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1887), 3. ↵

- Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler, 42. ↵

- Everett, “Revival of Interest in Etching,” 245. ↵

- Ibid., 246. ↵

- Notable recent studies include Joby Patterson, Bertha E. Jaques and the Chicago Society of Etchers (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2002), as well as numerous museum exhibitions across the country. ↵

- Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler, 39. ↵

- John Taylor Arms, “John W. Winkler, Master of Line,” Prints 4, no. 2 (1934): 1–4. ↵

- H.R. Robertson, The Art of Pen and Ink Drawing, Commonly Called Etching (London: Winsor and Newton, 1891), 27. ↵

- Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler, 51. ↵

- William Gaunt, Etchings of Today (London: The Studio, 1929). ↵

- References to “the autographic art,” abound: see Pedro J. Lemos’s 1916 article entitled, “California and Its Etchers—What They Mean to Each Other,” in Art in California, 113, uses that precise phrase; John Taylor Arms suggests that etchings are “as autographic of their creator as his handwriting, his voice, his mental processes.” See “Childe Hassam, Etcher of Light,” Prints 4, no. 1 (1934):1. ↵

- Sheldon Cheney, “Notable Western Etchers,” Sunset 21 (1908): 743. ↵

- From an interview with Aline Kistler as quoted in Aline Kistler, “Roi Partridge, Etcher,” Prints 4, no. 4 (1934): 18. ↵

- All of these advertisements appear in the advertising section of individual issues of the 1908 volume of Sunset magazine. Most of the schools advertised in every issue during this period. ↵

- Gavin Jones, Strange Talk (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999: 10. ↵

- Jones, Strange Talk, 30. ↵

- Brander Matthews, Parts of Speech: Essays on English, 1901, as quoted in Jones, Strange Talk, 32. Matthews’ sentiment is part of a long genealogy of anxiety about linguistic purity, a full exploration of which is beyond the scope of this paper. ↵

- A brief review of the Chinese characters in Winkler’s etchings by a colleague suggests that the majority are fairly accurate transcriptions, although individual characters often appear backwards in the prints because he copied them directly onto the plate from life. ↵

- The clarity of this sans serif font is also a striking contrast to the fraktur and similar blackletter typefaces used in German-language publications throughout the United States in the first decades of the twentieth century—a matter worthy of further consideration. ↵

- Cherny, “Patterns of Toleration and Discrimination in San Francisco,” 131. ↵

- Mark Ellis and Panikos Panayi. “German Minorities in World War I: A Comparative Study of Britain and the USA,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 17, no. 2 (1994): 239–40. ↵

- Benjamin Paul Hegi, “‘Old Time Good Germans’: German-Americans in Cooke County, Texas, During World War I,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 109, no. 2 (October 2005): 242, n. 20. ↵

- Ibid., 242. ↵

- Liesl K. Miller, “The Great War: Ethnic Conflict for Chicago’s German-Americans,” OAH Magazine of History 2, no. 4 (Fall 1987): 48. ↵

- Ellis and Panayi, “German Minorities in World War I,” 243. ↵

- Amber Smith, “A Full Measure: The German-Americans in Tracy, California 1917-1918,” Pacific Historian 28, no. 1 (1984): 54. ↵

- Ibid., 55. ↵

- Tibor Glant, “The War for Wilson’s Ear: Austria-Hungary in Wartime American Propaganda,” Hungarian Studies Review 20, nos. 1–2 (1993): 34. ↵

- Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler, 60. ↵

- In the 1920s, Winkler traveled to Europe, where he searched for news of his family in Austria—but they had all been killed during the war. Winkler never identified his family or his own birth name, but the war clearly put pressure on his sense of home and national identity. For another example of the influence of World War I on German American artists and their aesthetics, see Louise Siddons, “Finding Their Place: The Regional Landscapes of Jacques Hans Gallrein and Doel Reed,” Great Plains Quarterly 34.1 (Winter 2014): 63–90. ↵

- Ellis and Panayi, “German Minorities in World War I,” 242. ↵

- For example, along with the hundreds of nameless internees, Karl Muck, erstwhile director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Karl Oscar Bertling, a Harvard professor, were arrested and contained in Fort Oglethorpe. Like the better known Japanese internment program of World War II, the German camps targeted people who were perceived to be in vulnerable geographic locations—in other words, Germans on the East Coast were disproportionately interned. It is therefore unlikely that Winkler was ever in danger of being sent to a camp himself. For an extended discussion of the ways in which dialect speech negotiates power relations between social groups, see Jones, Strange Talk. ↵

- Gerald Davis, “‘Orgelsdorf’: A World War I Internment Camp in America,” Yearbook of German-American Studies 26 (1991): 256. The passage translates: “Only livestock lives in B / In A the cream of Germany.” ↵

- Millman, Master of Line: John W. Winkler, 60. “Winks” was John Winkler’s nickname, which Millman uses throughout her text to refer to the artist. ↵

- Ibid., 159. It is interesting to note that this box was produced in the middle of World War II. ↵

- Josephine Clifford, “Chinatown,” Potter’s American Monthly 14 (1880): 360. ↵

- Clifford, “Chinatown,” 357. ↵

- Rast, “The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco’s Chinatown,” 47. ↵

- Jones, Strange Talk, 10. ↵

- Ellis and Panayi, “German Minorities in World War I,” 239. ↵

- “Have No Weak Pity,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, April 6, 1918, 4, as quoted in Michael D. Thompson, “Liberty Loans, Loyalty Oaths, and the Street Name Swap: Anti-German Sentiment in Ohio, Spring 1918,” Yearbook of German-American Studies 33 (1998): 152. ↵

- This detail is unfortunately only visible when looking at the original print, rather than in reproduction. ↵

- Charlot is quoted in Fenton Kastner, Etchings Drawings and Boxes: John W. Winkler, A Selection for the Exhibition at California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1974), 4. Kastner does not cite the original source. ↵

About the Author(s): Louise Siddons is at Oklahoma State University.