The Levee: A Photographer in the American South

Curated by: Nathaniel M. Stein

Exhibition schedule: Cincinnati Art Museum, October 5, 2019–February 2, 2020

Exhibition catalogue: Nathaniel M. Stein, with Sohrab Hura, The Levee: A Photographer in the American South, exh. cat. Chicago: Candor Arts, 2020. 128 pp.; 57 color illus.; 8 b/w illus. Cloth: $84.00 (ISBN: 0931537460)

Self-taught photographer Sohrab Hura’s first museum exhibition, The Levee: A Photographer in the American South, took place in a single gallery at the Cincinnati Art Museum (October 5, 2019–February 2, 2020), curated by Nathaniel Stein, associate curator of photography (fig. 1). The images of people and landscapes record Hura’s April 2016 road trip along the Mississippi River, from its confluence with the Ohio River outside Cairo, Illinois, to Pilottown, Louisiana. His trip was a response to a boat journey his father had taken along the same river two months prior, one that he had documented for his son in cell phone photographs and text messages. Hura’s father had traveled to Louisiana from India as a cargo boat captain for the India Merchant Marine. Because of immigration rules confining him to his ship, he could never go on land. By car, Hura traveled about 640 miles, paralleling, in the last leg of his journey, the final eighty or so nautical miles of his father’s trip from the Gulf port of Pilottown to New Orleans.

Hura’s seventy-two black-and-white, untitled inkjet images (printed in 2018) documenting his journey poignantly express themes of place, perspective, separation, and longing for deeper connection between the two men and humanity at large. The levee of the title refers to an embankment; it forms a physical barrier between road and river. While virtually none of the photographs depict levees, Hura uses the word metaphorically. In his artist’s statement, he explained, “Just as it was with my father, there was always a levee between the river and me as well. My father had been on the water but had not been able to touch land. I was on land but had barely been able to touch water. Together we got a glimpse of the delta from our own sides of the levee.” Near the exhibition entrance, the title panel (on a temporary wall partition) functioned like a levee. On the panel’s opposite side were Hura’s father’s images. What was beyond the other side could not be seen by viewers immediately, just as Hura’s father could not see much land beyond levees, and Hura saw the South from land near the river, but hardly depicted the river.

Hura and his father had had a fraught relationship for decades, marked by spatial, temporal, and emotional distance, in part because Hura’s father was often absent, on the sea. Nonetheless, Hura’s father stayed in touch with his son during his journey. His cell phone images gave his son a glimpse of the area he would visit accompanied by brief text messages in English that verbalized his thoughts.

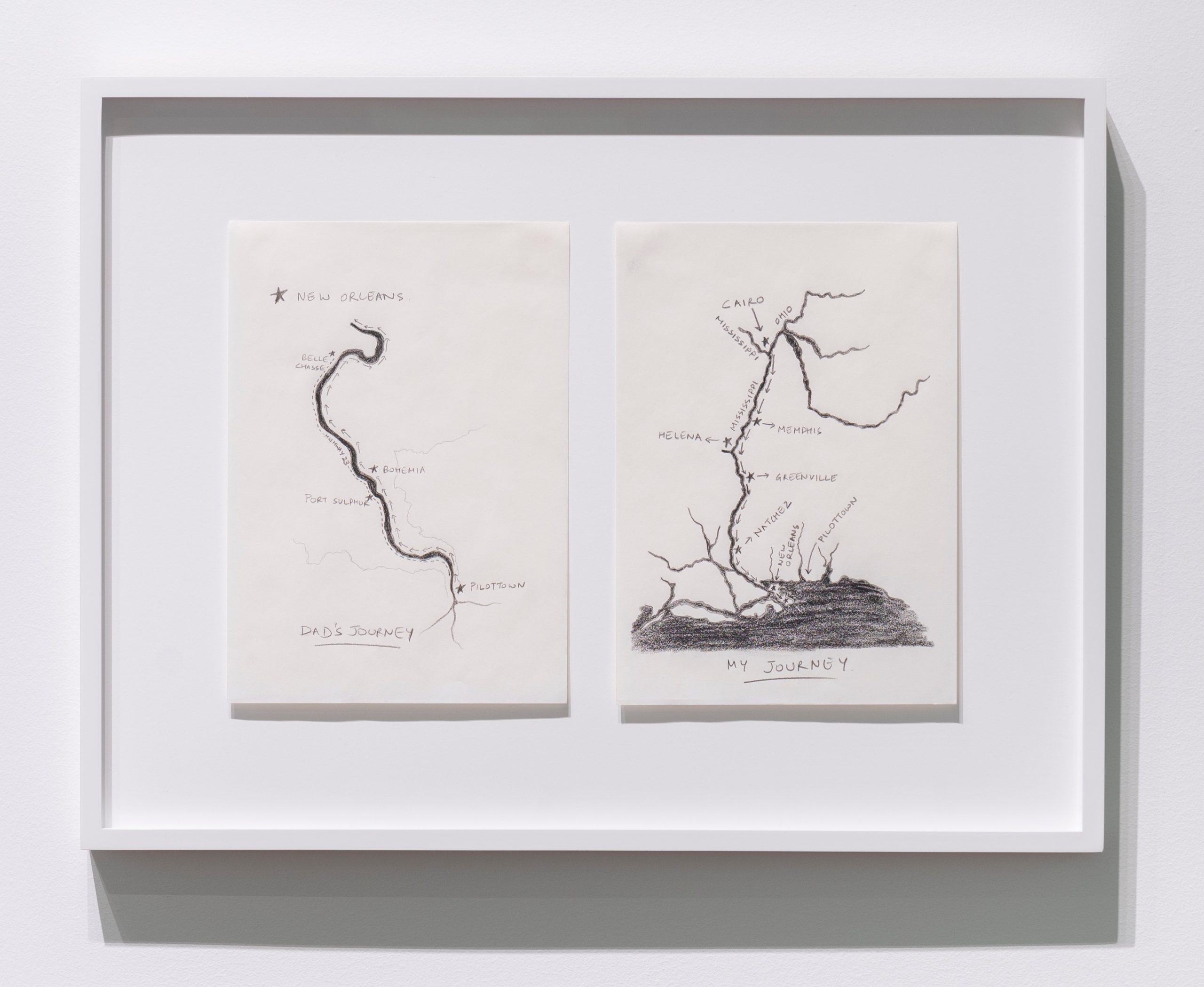

In the exhibition, next to Hura’s father’s images and tidings were two large graphite maps by Hura, entitled My Journey and Dad’s Journey, both 2018 (fig. 2), that translate the Mississippi River, tributaries, and delta into grainy, snakelike lines. Arrows trace Hura’s trip south and east with stars indicating cities he visited—Cairo, Memphis, Helena, Greenville, Natchez, and New Orleans—and his father’s journey north and west from Pilottown past Port Sulphur, Bohemia, and Belle Chase to New Orleans, names hand-printed in capital letters. The simple diagrams, with their ragged contours, contributed to the journal-like quality of the exhibition.

Displayed in conjunction with Hura’s twelve-inch-square photographs were slightly enlarged reproductions of Hura’s father’s six panoramic, generalized, shipside pictures (7 x 9 in. each), along with five phrases taken from the phone texts, handwritten by Hura’s father at Sohrab’s request (fig. 3). These eleven items were cleverly mounted without mats on a white floating wall partition near the entrance, on the opposite side of the exhibition title. The reality and metaphor of a raised barrier informed the entire installation, perhaps most cogently in Hura’s father’s request, “When you get the chance tell me what’s beyond the levee.” The solicitation suggests an interest in not just what Hura saw but also what he perceived and felt while traversing a foreign land. Both men reached out with photographs, hoping to bridge the geographical and emotional gaps between them. Born in in Chinsurah, West Bengal, India, in 1981, and currently living in New Delhi, Hura was very conscious of his position as an outsider and a person of color while traveling in the United States during a contentious presidential campaign, when the American South was often in the news. Aware of stories about guns, violence, racism, and Donald Trump, his father had cautioned, “Be careful when you are in New Orleans, [h]eard it’s not very safe.” Instead of experiencing the xenophobia of others, Hura felt generally accepted by Southerners, even though they did not invite them into their homes. Many of these images are of outdoor, public, or liminal spaces, often marked by boundaries of architectural thresholds, property lines, or landscape features. Rather than documenting politics or social discourse, Hura created a personal, stream-of-experience response to a specific time and place.

The exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum is part of a much larger project for Hura. He originally produced these works while participating in a loosely collaborative documentary project, Postcards from America, that existed from 2011 to 2016, and he involved groups of artists who traveled though specific American places to create new documentary responses to the United States. Funded by San Francisco’s Pier 24 Photography, participants held a pop-up exhibition and wrap party at the end of each trip. For these image-makers, historic American touchstones include Farm Security Administration photography (particularly that of Walker Evans), Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), and Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004).1 Hura also drew on a long tradition of Indian river photography from the British colonial period to more contemporary figures like Raghubir Singh, Atul Bhalla, and Rishi Singhal.

Because Hura has not specified a single authoritative layout, the images create different inflections depending on how curators group, sequence, and space them. The Levee first appeared in Experimenter Gallery-Ballygunge Place, Kolkata, India, as part of the group exhibition Searching for Stars Amongst the Crescents (Fall 2019). Given the smaller room footprint in India, four columns of photographs were stacked nearly floor to ceiling on white walls. At the Cincinnati Art Museum, the images were hung closely in a nonsymmetrical, parallel double row, punctuated by broken lines or blank square spaces. In the two versions, the works were presented at an approachable scale in warm, natural wood frames, matted with comfortable margins. The reference point for both hangings was musical notation that can register a fluid, abstract, and nonvisual sensory experience. The display mode focused on flow and resonance, unifying the whole body of work. The evocation of music was not only symbolic; ambient sound, mostly birdsong, played from a twenty-minute looping audio recording that Hura made on the grounds of the Elgin Plantation Guest House (c. 1850s) in Natchez during a brief stay there. For both the photographer and museum visitors, the unadorned chirps and trills, as well as faint twenty-first-century road noise and breeze captured by an open microphone, provided a layer of peacefulness. The unexpected, natural sounds in the gallery disrupted a typical, detached way of looking to impart a contemplative mood and enrich the emotional complexity intimated by the photographs, suggesting an approximate experience of being outdoors. For Hura, the blue-green color of the walls—painted in PP&G Catalina, selected in consultation with the curator—was an aesthetic tool for lifting up the work, like the birdsong. In his cultural world, color significantly is about vitality and the richness of presence. In the artist’s statement posted at the gallery entrance, Hura declared, “As it had been for sailors searching for land, birds now became my guides as I looked for the beginnings of water, leading me through the blues of the wetness of the land. The America I found on the way was not quite the same as the one that my father had imagined.” Hura found the delta to be lush, soft, and complicated, not the harsh place his father anticipated.

Significantly, birds and birdhouses appeared throughout the exhibition, beginning with the black-and-white title panel featuring a lone bird in profile perched on a bare tree branch hovering over a gray winding band representative of the river (fig. 1). Birds occasionally appeared in the photographs as surrogates for human characters, sometimes suggesting the proximity of land and water or serving as guides to the river, frequently demonstrating gestures of care. For instance, centered in one photograph is a birdhouse mounted on a tall pole alongside a chain link fence. Four birds fly toward the home, apparently placed for them by the inhabitants of the two modest prefabricated modular houses in the lower left. In a second print, there is a fence that recedes at a diagonal (fig. 4). Just on the other side of the barrier, wedged on a narrow band of grass before ornamental grasses, there are two plastic flamingos; they stand side by side but are visually separated from each other by the metal fence stake and distant telephone pole that bisect the composition. Although physically close, like father and son, they see the landscape in front of them—and through a rectangular wire grid, metaphorically like their grid of preconceptions—but not each other. In another spare image, five somewhat blurred seagulls hover in a pale gray sky. Could both Hura and his father have seen the same avian creatures?

Some of the scenes, such as a winding dirt road in a flat landscape, the prow of a cargo ship in a river, a tangle of saplings in a flooded stream, a single weeping willow, a water snake swimming in shallow water, a torn bit of cardboard on the ground amid dense, dead underbrush, and Hura’s foreshortened, jeans-clad crossed legs captured while reclining on a hazy riverbank, are somewhat banal and could have been made almost anywhere in the United States. Only one photograph truly documents the specificity of the American South: the deadpan, cropped frontal image of a metal structure with a small, wall-mounted exterior air-conditioning unit. The large business sign propped in front of the roof peak gives the telephone number and address for Dad’s Restaurant on State Highway 23 (which runs between Pilottown and New Orleans). The cropped banner in the lower right advertising crawdads underscores the specificity of the Louisiana site.

Almost all of these relatively quiet and formal photographs use standard focus, a closed or relatively shallow picture plane, and centrally placed subjects, shot with a medium-format film camera. As a whole, the straightforward, stripped-down images convey compositional stability and directness, a candor Hura found among the people he met along the levees. That forthrightness and spare quality were also evident in the installation that contained no captions or interpretive labels. On the one hand, this allowed viewers to focus on the images and sound, and draw their own conclusions. On the other, it promoted the American South as constrained, sparsely populated, mostly rural, working class, and rather dull. It also denied location specificity overall and made the figures represented seem more like types (for example, funeral visitor, street preacher, dining couples, promgoers) than individuals.

While the introductory exhibition text called the photographs of people portraits, none of the subjects were identified in the untitled works, and some compositions appear more as genre scenes or snapshots, such as a young woman sitting in a booth at a pizza joint and an image of a casually clad couple embracing on a curb near the river. Two of the most notable prints are close-ups of unidentifiable pairs of standing people seen in half-figure, each with a white woman supporting an elderly person with her right hand. In one outdoor image, we see a heavyset female with long, frizzy blond hair from the rear, grasping the upper back left arm of bald, bespectacled man, guiding him toward a building. In the other, shot from neck to thigh, a woman wearing pearls, a checked blazer, and a black blouse tenderly holds the wrist of an African American woman clothed in a white apron over a long-sleeved white cotton shirt. Such images demonstrate gentle care and affectionate interdependence. Like the flamingos, the pairs stand side by side but do not see each other.

Perhaps the most remarkable photograph in the exhibition depicts a stocky African American youth in dark sweatpants and gym shoes hoisting a double box spring with a black fabric bottom on his shoulder and upper back (fig. 5). He pauses at twilight in a modest residential neighborhood on a gravelly patch near the edge of a yard, before a long puddle. On his t-shirt is a drawing of a figure seated before an angular graphic that could read as angel’s wings. With his bowed head and outstretched arms, the young man appears Christ like, bearing a burden akin to the cross (even though this piece of bedroom furniture is more cumbersome than heavy). This resonant image conveys multiple, contradictory impressions—discomfort, shelter, resignation, reluctance, protection, stoicism, endurance, strength, duty, care, and hope for a new beginning. Museumgoers could explore and discuss these themes in additional work via copies of Hura’s five books and printed material by numerous other artists available for browsing at a community table in the exhibition gallery (fig. 1). The picnic benches evoke casual, intimate, face-to-face gatherings in warm climates, underscoring the longing for meaningful, personal connection in the display.

In The Levee, Hura gives visual form both to his impressions of connected life along the Mississippi River and to his own disconnectedness from this life and that of his father. The exhibition offered a fresh, subjective perspective that made Southern American identities, personal and natural, seem fragile and dreamlike, punctuated by intermittent bird calls.

Cite this article: Theresa Leininger-Miller, review of “The Levee: A Photographer in the American South,” Cincinnati Art Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10739.

PDF: Leininger-Miller, review of The Levee

Notes

- Robert Frank, The Americans (New York: Grove, 1958); Alec Soth Sleeping by the Mississippi (Göttingen: Steidl, 2004). ↵

About the Author(s): Theresa Leininger-Miller is Professor of Art History at the University of Cincinnati