The Modernist Appalachian Aesthetic: The Art of Patty Willis

Recent scholarship on American modernism has highlighted regionalism and rural modernism and argued for the importance of art made outside of and in tandem with urban centers.1 One absence, however, is a discussion of modernism in the Appalachian region, which encompasses the land mass around the Appalachian Mountains, ranging from New York to Georgia and westward into Ohio. Appalachian Regionalism should be distinguished as a rich mode of artistic production, one that is unique in that it consists of equal parts high and low, or fine and folk art. In addition to this combination, numerous themes emerge within established Appalachian subject matter, including those related to religion, traditional storytelling, acknowledgment of or disdain for environmental labor, and a distinctive respect for nature, based on the ingrained culture of foraging and living off the land that is inherent to many Appalachian communities.2

The work of Appalachian modernist Patty Willis (1879–1953), a painter, printmaker, designer, and art historian, has never been studied at length. Contemporaries of Willis, such as fellow West Virginian Blanche Lazzell (1878–1956) and New Yorker Charles Burchfield (1893–1967) made works with similar subject matter and aesthetic sensibilities. Although her artistic contributions had less national reach than those of Lazzell or Burchfield, her work carries a distinctly Appalachian aesthetic, which is seen in The Earth and the Sky (fig. 1), as well as art made by other modernist peers in the region. Appalachia has been overwhelmingly sequestered within national discourse, specifically when it comes to labor and economic rights and its history within the rest of the country. Recuperating Willis’s career redresses some of this lacunae. Her legacy spans significant twentieth-century modernist movements centered on urban art worlds and minute, local histories of Appalachia; this role as a bridge between these distinct communities highlights the particular nature of Appalachian Regionalism, which developed in places that, while rural, were not, in fact, inaccessible from major urban centers.

Patty Willis (fig. 2) was born in 1879 in Jefferson County, West Virginia, to a prestigious family. Her family lineage can be traced to George Washington, as her mother was part of the last generation of Washingtons to live at Mount Vernon. Willis showed interest in the arts at a young age and was lucky in that Jefferson County, West Virginia, because of its proximity to large cities such as Washington, DC, and Baltimore, provided more access to urban culture than many other parts of Appalachia. In 1908, she enrolled at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington DC, graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago by 1913, and later attended Pratt Institute in New York City in 1917. She also worked as an occupational therapist in an army hospital during World War I, rehabilitating wounded soldiers.3 In 1917, she made her first trip to the Provincetown art colony in Massachusetts, which at the time was considered the “largest art colony in the world” and the place to be for a serious artist.4 She showed two paintings that year with the Provincetown Art Association; her relationship with the colony would continue for the rest of her life. Following the war, Willis traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East, studying with Fernand Léger in Paris at the Académie Moderne. During the 1920s and 1930s, her work was shown in biennial exhibitions at the Corcoran Gallery, the Carnegie Institute, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the 1939 World’s Fair.5 She returned to Provincetown several times, where she was an avid participant in the community, along with Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, Marsden Hartley, and countless others. Willis visited New York City in the winter months and also spent considerable time in her home state of West Virginia.

Like other artists of her generation, Willis worked across various media and shifted back and forth between realism and abstraction during the course of her career. These divergent styles compete with one another on the same canvas in experimental pieces like The Earth and the Sky, likely completed in 1942 as a wedding gift for a family member.6 In the painting, Willis depicts a scene that she saw often while home in West Virginia, a road that connected Charles Town to Harpers Ferry. The Harpers Ferry gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains can be seen in the distance of the composition, a historically significant area both geographically (connecting Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland along the Potomac River), and strategically during the Civil War. Within the composition, Willis has abstracted many of the shapes to resemble cut paper or Lazzell’s Provincetown printing technique.7 Despite the abstraction, she has taken great care in rendering detail within the landscape, creating a sense of movement with her depictions of trees in the foreground and the parting cloud structures of the background. A lone person can be seen walking on the long, winding road, either toward or away from the viewer. The road in modern, Regionalist works is something that is often used as a metaphor for transition, migration, and progress. In Rural Modern: American Art Beyond the City, Amanda C. Burdan notes how “the modern road, and specifically the rural road, is free of traffic; more than that, it is empty to the point of loneliness. . . . Men’s work is suggested, but the activity itself is unseen. Instead there is no action on these new roads, questioning the need for them at all.”8 Perhaps, then, Willis was commenting on the modernization of West Virginia. More likely, however, she was depicting a scene that was closely tied to familiar views from her upbringing and which denoted a spiritual connection to the land and her situation as an artist.

In order to comprehend the art of Patty Willis, it is important to understand the culture of Appalachia. At the time, West Virginia was not a welcoming place for female artists, and gender roles embodied traditional ideas that were ingrained in Appalachian culture. Since seceding from Virginia during the Civil War, the state occupied an awkward position of being too North for the South and too South for the North, despite its abolitionist sympathies. At the end of the nineteenth century, West Virginia became a hub for environmental labor in coal, steel, and timber, and it nurtured a unique cultural heritage fed by waves of immigrants; first came the German, Scottish, and Irish, and later those from Eastern Europe. By the early twentieth century, stereotypes about West Virginia developed that characterized Appalachia as a backward, poverty-stricken region that had little to contribute to the nation but labor. This was enhanced by the Mine Wars (c. 1900–1921), which focused national attention on West Virginian mineworkers and exploitative practices.9

In thinking about Appalachian Regionalism as it applies to Willis’s body of work, many compositions feature distinctive symbols of her life and upbringing in West Virginia. While much of Appalachia was conservative and Christian, Willis was progressive, possibly even communist (it was alleged she attended communist meetings in New York City).10 She simultaneously lived a demure existence as a religious West Virginian, while maintaining a traveling bohemian lifestyle. Throughout her life, she was active in the church and carried out mission work in areas of the state that were isolated and poverty stricken. Religion was often tackled in her work through the use of the sublime, a long-standing aesthetic category that signaled spiritual concerns through nature.

The synesthetic representation of an untitled painting by Willis, most likely from the later 1920s (fig. 3), alludes to one of the principal jobs in Jefferson County at the time, working in an apple orchard. An heirloom tree, a type of tree that was in decline at the time as small diverse orchards were replaced by larger monopolies, dominates the center of the painting, ready to be picked. Willis spent much of her life studying and drawing the intensive labor processes of apple orchardists and their hired immigrant laborers, as her family home was in close proximity to many of the major orchards that supplied the tristate area with produce. Additionally, the apple held religious significance to Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden, which would have resonated with Willis’s devout nature. The color choices in the surrounding trees and mountains indicate it is set in late summer to early autumn.

Like the work of Charles Burchfield, many of Willis’s paintings of nature have an energetic movement to them. For example, Burchfield’s Summer Solstice (1961–66; current whereabouts unknown), in which Burchfield references the changing seasons as well as the glorification and demise of the American chestnut tree, is similar in its composition to Willis’s untitled work.11 While Burchfield’s works often focus on weather, Willis’s paintings instead focus on the energy of the place she is capturing. In both, the sublime is palpable, from the implementation of wild color to the application of the playful, animated brushstrokes.

In addition to similarities between Willis and Burchfield, it is equally important to note the influence that Provincetown artist Blanche Lazzell and her Provincetown printing technique had on Willis’s compositions. Fellow West Virginian Lazzell is now considered a pioneering female modernist printmaker in America; however, she enjoyed little recognition in her lifetime. Lazzell visited Provincetown in 1915, finding solace with the modernist expat community and helping to establish the Provincetown Printers. She never settled there permanently, always returning to West Virginia, but spent most winters and summers in residence.12 Willis was often in Provincetown during Lazzell’s tenure, and compositions such as Weather Cock (fig. 4) from 1935 show a clear relationship to Provincetown and the sea. Lazzell’s The Seine Boat (fig. 5), a woodcut from 1933, depicts comparable subject matter in a similar color palette yet also showcases her white-lined woodblock printing technique, based upon nineteenth‑century Japanese ukiyo-e prints. Willis also experimented with Lazzell’s Provincetown printing technique using Appalachian subject matter, as is apparent in an undated printing proof of an apple tree (fig. 6) flanked by the striking Appalachian Mountains, making it clear that the landscape is West Virginia and not Massachusetts. However, the most significant connection between the two women was on a personal level; they chose to be independent, unmarried, and cultured artists who simultaneously valued religion and tradition. They showed pride in their Appalachian upbringing, appreciated experimentation, and demonstrated a fluency between craft and academic endeavors.

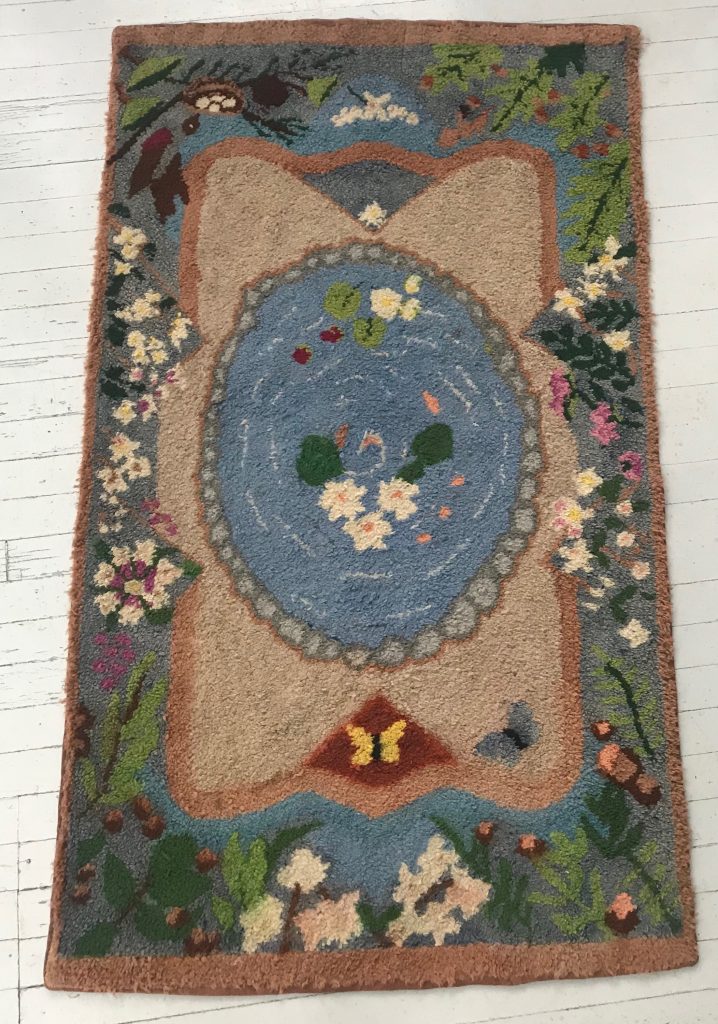

While maintaining painting and drawing was integral to Willis’s artistic practice, she also delved into folk art and traditional Appalachian crafts. She created several decorative designs for hand-painted furniture, dishware, pottery, wallpaper, and interior rugs. An untitled hooked rug design by Willis features a bird’s eye view of a koi pond and surrounding garden filled with abstracted local flora and fauna in the background—Queen Anne’s lace, a cabbage white butterfly, ferns, a songbird nest, and bleeding hearts (fig. 7). Lazzell also designed rug patterns, including Sunflowers (fig. 8) from 1928. Hooked rugs also feature in interior views by American modernists, including Charles Sheeler, whose photographs and paintings of rural farmhouses include Quaker furniture and other folk art objects.

In a similar manner, Patty Willis featured antiques and traditional items synonymous with Appalachian culture and personal family history in her compositions. In Portrait of Elizabeth R. Washington (fig. 9), the artist emphasizes the Washington family lineage by prominently including a piece of eighteenth-century Mount Vernon china, featuring a distinctive blue and white pattern, which had been passed down by the family. In the background of the portrait is a small circular likeness of the now-destroyed St. George Episcopal Church, a pre-Revolutionary building located in Jefferson County. The inclusion of this object demonstrates familial piety and their continuous roots within the state. Willis uses the placement of a red geranium as a symbolic reference to domesticity, cultivation, and caretaking abilities, much like the Regionalist Grant Wood (1892–1942) did in the portrait of his mother, Woman with Plants (1929; Cedar Rapids Museum of Art).

Both The Cellar Door (fig. 10) and The Golden Chain is Broken (fig. 11), likely from the late 1920s or 1930s, depart from Willis’s normal subject matter, yet they invariably provide a sense of her Appalachian identity and cultural linkages to storytelling, her faith, and her training as a modernist painter. It is believed that The Cellar Door was completed while Willis was in Provincetown and depicts the view across the street from her studio. The subject matter subtly addresses the taboo subject of prostitution, which Willis may have witnessed. Willis’s use of color and the modernist technique of depicting multiple viewpoints break up the composition into segments, reminiscent of the tiers employed in Renaissance altarpieces that denote artistic hierarchy, such as the Ghent Altarpiece (1432; St. Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent) by Hubert and Jan Van Eyck (Flemish, c. 1385/90–1426 and 1390/95–1441). In the case of The Cellar Door, these tiers denote importance within the painting and play with the representation of class and labor. In the immediate foreground, figures resembling nuns or the Virgin Mary are cut off by the bottom of the canvas. Below them, Willis painted “The Cellar Door.”

Willis’s use of text appears in a handful of works and was perhaps influenced by the use of text in Cubist works such as Ma Jolie (1911–12; Museum of Modern Art) by Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973) or the contemporary illustrations of Violet Oakley and Jesse Wilcox Smith. Her training with Léger might have also factored into this stylistic decision. Above the women, three men sit on a bench in front of an open door, presumed to be the cellar door of the title. Because of their casual positions, these men may be laborers taking a break or waiting their turn for something. Above the three men, a gentleman slowly climbs the staircase toward the outline of a nondescript woman partially visible in an open window. Within the window are three small round spheres, which may be a reference to Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of prostitution (among other things).13 As such they symbolize and reinforce the taboo subject matter. What cannot be known, however, is what exactly Willis meant with this work. Did she sympathize with prostitutes and prostitution? Was she perhaps, associating labor with prostitution through the inclusion of the workers on the bench? Whatever the intent, the theme of religion is clear and regularly appeared in her compositions, whether subtle or blatant.

Another artwork that similarly reflects her Appalachian identity and interest in religion and modernism is The Golden Chain is Broken. The cross-shaped painted title of The Golden Chain is Broken may reference a verse from the Bible (Romans 8:38–39) and, when combined with the religious connotation of the fish, could imply a religious meaning for the painting. However, other potential readings also emerge. The Golden Chain is Broken also formed the refrain to a popular labor song called “The Coming of the Light,” which appeared in the 1892 book, Chants of Labor: A Song Book of the People.14 In West Virginia, some miners engaged in the Mine Wars, making labor and the fight against capitalist enterprises an Appalachian concern. Willis was rumored to be a member of the Communist Party and therefore would have been sympathetic to the labor movement. Finally, the rainbow trout is featured prominently in the center of the painting and can be identified by its green coloring, pink stripe, and speckled skin. A North American fish found in the rivers of West Virginia and the Potomac during the 1930s, the rainbow trout was in jeopardy from overfishing and local farming and orchard operations, implying an ecological interpretation.

In combining labor and religion with the rainbow trout—dead and presented on a broken plate, surrounded by dull, lifeless colors and a bolus of green algae with bits of chain and a hook—it is possible that Willis is making an ecological assessment about the toll of mineral extraction on the environment. The fish may be a stand-in for the exploitation of the mineworkers, as they are used up, discarded, and replaced. As Bill Brown explains in “Thing Theory,” the dynamic between a useful, animate object, and a broken, inanimate one brings attention to human interaction and the object’s functionality.15 In light of this, maybe Willis is returning agency to the non-functional broken plate and the dead fish, highlighting the negligence of human actors.

In the 1930s, Patty Willis also designed several Works Progress Association murals, including at least three within Jefferson County and several others regionally. Unfortunately, none of these murals survive in their original forms. However, they are presumed to be preserved underneath layers of paint in their original locations. A single photo exists of her fresco mural project in the entrance hall of Charles Town High School, titled Cultivation: Wheels of Science and Progress and Nature and Recreation (fig. 12) and depicting scenes from Jefferson County. A study for Nature and Recreation preserves her ideas for the color and composition of the mural and features emotive plants and animals from Jefferson County, painted in a synesthetic manner.

Finally, Willis was a pioneer in the study of art history in West Virginia, acting as a lecturer regionally in addition to her pursuits in fine art. Her directory, “Jefferson County Portraits and Portrait Painters,” was the first of its kind in the state and was published in 1940. Her views on labor and the arts is clear in this excerpt:

Artistic development coincides with the growth of a remarkable material prosperity and a resulting release of human energy from the all-absorbing task of securing the bare necessities of life. If it is true that there is such a correlation between economic condition and the cultivation of the arts, we should be able to discover in any region a rise and decline in interest in the arts.16

As Willis points out, artmaking provided prosperity and enriched the local economy. In Appalachia, the cultivation of the arts—perpetuated by women such as Lazzell and Willis—gave rise to a particular form of modernism.

Patty Willis died in 1953 and her work was last shown posthumously at the 1986 bicentennial exhibition in Jefferson County. Although Willis spent considerable time in big cities, studied at Pratt and with Léger in Paris, and was a member of the Provincetown art colony, she always included aspects of Appalachian culture in her work. Her compositions, from a simple hook-and-eye rug pattern to detailed modernist paintings, laid claim to the rich heritage of Appalachia. In analyzing the work of Willis, whose career has fallen into obscurity, one can trace numerous connections to other high modernist figures and movements, as well as a rural aesthetic particular to Appalachia. Hopefully, this study will encourage others to consider how the diverse region of Appalachia affected and was affected by larger movements in American modernism, as seen in the art of Patty Willis.

June 21, 2020: An earlier version of this article inaccurately suggested that Elizabeth R. Washington remained unmarried; lacked clarification on Willis’s alleged involvement with communism; and gave the wrong date for the Jefferson County bicentennial exhibition (it was 1986, not 1975.)

Cite this article: Alison Printz, “The Modernist Appalachian Aesthetic: The Art of Patty Willis,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9910.

PDF: Printz, Modernist Appalachian Aesthetic

Notes

- Amanda C. Burdan, Rural Modern: American Art beyond the City, exh. cat. (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2016), and Lauren Kroiz, Cultivating Citizens: The Regional Work of Art in the New Deal Era (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2018). ↵

- Many residents from Appalachia, and particularly West Virginia, have an intense knowledge of plants and animals from within the state, which is often passed down generationally. Due to the history of poverty in the region, it was necessary to live off the land, or forage, requiring intense knowledge of nature to avoid harm. ↵

- “Patty Willis: Biography,” http://www.pattywillisartist.com/biography.html, accessed April 21, 2018. ↵

- Alexander J. Noelle, The Tides of Provincetown: Pivotal Years in Americas Oldest Continuous Art Colony (1899–2011), exh. cat. (New Britain, CT: New Britain Museum of American Art, 2011), 5. ↵

- “Patty Willis: Artistic Training,” http://www.pattywillisartist.com/artisticCareer.html, accessed April 21, 2018. ↵

- Interview with Walter Washington, great-nephew of Patty Willis, May 2018. ↵

- This printing technique used only one woodblock with separations between each color, as opposed to multiple woodblocks for each color separation. See John Cuthbert, Early Art and Artists in West Virginia (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2000), 205. ↵

- Burdan, Rural Modern, 29. ↵

- The Mine Wars were nationally known and gained much sympathy from the people of Appalachia, as miners stood up against coal companies for basic human rights, which ultimately led to bloodshed. See Drew A. Swanson, Beyond the Mountains: Commodifying Appalachian Environments (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018); John Alexander Williams, Appalachia: A History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); and Kevin Barksdale, Blood in the Hills: A History of Violence in Appalachia (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012). ↵

- Interview with Walter Washington, May 2018, in which Washington remembered that a nephew of Willis suspected she attended meetings of the Communist Party in New York, but this information has not been definitively confirmed. ↵

- See “Background on American Chestnut Blight,” on the website Restoring the American Chestnut, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, accessed April 27, 2020, https://www.esf.edu/chestnut/background.htm. ↵

- “Blanche Lazzell,” Art & Artists, Smithsonian American Art Museum website, accessed June 2018, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/blanche-lazzell-2842. ↵

- To save his three daughters from poverty, a poor man attempted to marry them off, but without a saving them from poverty. The man attempted to thank Saint Nicholas, but in his piety, he would not accept the gratitude. In effect, Saint Nicholas became the saint of prostitutes and unwed women, as well as the gift giver at Christmas. “Who is St. Nicholas?,” St. Nicholas Center website, accessed April 4, 2020, https://www.stnicholascenter.org/who-is-st-nicholas. ↵

- Edward Carpenter, Chants of Labor: A Song Book for the People (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1892). ↵

- Bill Brown, ed., Things (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). ↵

- Patty Willis, “Jefferson County Portraits and Portrait Painters,” Magazine of the Jefferson County Historical Society 6 (1940): 21–22. ↵

About the Author(s): Alison Printz is a PhD candidate in Art History at Temple University