Seeing Empire

The United States is an empire. It is a nation founded on the brutal and legislated domestication of its internal subjects. The histories of the forced labor and death of Black and Indigenous people that underpinned the nation’s foundation structure the forms of racial capitalism that now underwrite its political and social relations.1 These structures also sustain its imperialist ideologies manifested, as they are, in events that might take place “elsewhere” or in the ways people are figured as threats at “home.”2 My work on the historical representation and material cultures of cotton continually returns me to this position.3

Deana Lawson brings to light the visual logic of the practices and processes of empire in Nation (fig. 1). Here are three young African American musicians. Two are seated; one is standing, texting. We only see him from the torso down, for over his head is a superimposed photograph of George Washington’s dentures. The orthodontic theme continues: one of the men, Ruben, wears a dental apparatus that Lawson had sprayed with gold, matching the sitters’ bright gold necklaces. For Lawson, gold references a pan-African heritage, while the gold mouthpiece also evokes associations with instruments of slave torture, creating a complicated expression of Blackness: powerful, beautiful, and vulnerable.4 There is another layer: the dentures, which we now know include nine teeth taken from unnamed African Americans who may have been enslaved on Washington’s plantation. The young man on the left, Killa Moe, clicks his fingers. No doubt a reference to the injustices of the criminal justice system and police brutality experienced by young African American men, he also leaves us with this parting shot: juxtapose Lawson’s photograph with any portrait of the slave-owning President and what we see is the racial capitalism that built this nation. Her work brings to the surface the (visual) logic of extraction and exploitation that underpins internal and external practices of Empire.5 In this country I teach art history as a non-White, immigrant settler trained in Black Studies as much as the history of art. For me, artists like Lawson demonstrate how this discipline offers important tools for historicizing empire and showing that these processes remain foundational to contemporary conceptions of the United States.

The plantation is for me the iconic image of the United States.6 Consider Francis Guy’s painting Perry Hall, Slave Quarters with Field Hands at Work (fig. 2).7 A rare depiction of enslaved people working, here African Americans are transformed into “hands,” a term that signified their status as property and categorized them according to labor while measuring productivity. How many hands would it take to harvest a field?8 Sheltered by the plantation manor and decoratively whitened, these picturesque enslaved figures are domesticated, productive subjects, carefully controlled. Along with the slave owners, we survey, assess, and measure the worth of those who toil in the fields. This is the visual logic of racial capitalism.

This viewing position creates what I call a speculative vision, a way of seeing the natural and human world through the lens of profit. Settler-colonialism, itself a speculative venture, brought this continent into view for Europeans. And the plantation is imprinted with this history of immense environmental transformation, of land clearances that displaced Indigenous communities whose disposability correlates precisely with the usability of African American captives forced to undertake this ecological clearing and harvest the profits.9

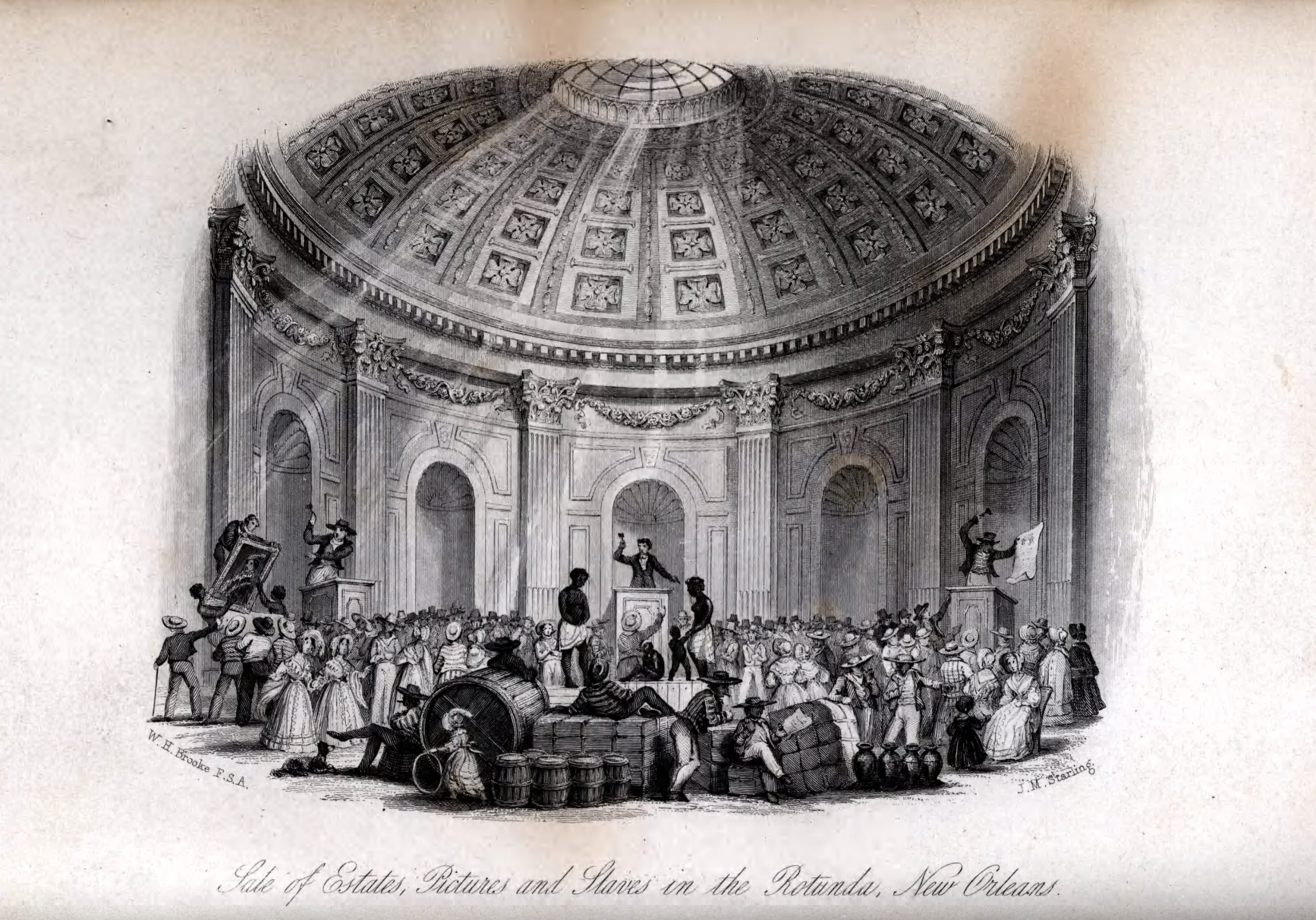

This painting shows us, too, a mode of visual accounting in which Blackness was read as an expression of value, and more often, future value. Frederick Douglass described it this way, “When cotton rises in the market in England, the price of human flesh rises in the United States.”10 This market relationship, graphically demonstrating the commodification of enslaved Americans, was visualized in other ways that reveal its implications beyond the stock exchange. For example, the title of J. M. Starling’s print Sale of Estates, Pictures and Slaves in the Rotunda, New Orleans (fig. 3) speaks for itself, showing, as Simon Gikandi has observed, how the institution of slavery and cultures of refinement are intricately enmeshed.11 Imagery like this reveals how American imperialism did not just affect non-White bodies but were the conditions of American art’s historical formation. Notice here the almost classicized rendering of these enslaved people—they appear as statues—a classicization of the enslaved body that would, a year later, be spectacularly materialized in Hiram Powers’s The Greek Slave (1843).12 In this way, the print materializes how the abstraction of enslaved African Americans into chattel also produces Whiteness as a normative subject position.

In Starling’s print, Black slaves transformed into commodities are interchangeable with the pictures being sold beside them, and the pictures in which they are circulated. The gaze of the viewer—the buyer—becomes an apparatus for the projection of desire and the attribution of value. There is a correlation here between the aesthetics of connoisseurship and the dynamics of the racialized gaze: both are connected by the speculative logic of the market.

This is carried forth in other disconcerting ways by contemporary artists like Deana Lawson, who interrogate racial capitalism’s exploitative logic, formalized in the production of art that frames certain bodies as sites of extraction. Leonardo Drew, in his sculpture Number 25 (fig. 4), takes this further, summoning up histories of the plantation that do not simply return us to the figure of the slave. The piece is a large cotton wall composed of several smaller cotton bales held together with wax. Drew painstakingly compiled the bales himself. With its semblance of uniformity, along with the mass of fibers and threads that emerge from its surface, the piece evokes the extractive logic of the plantation regime. Its materiality and production powerfully visualize the continued presence of this extractive logic in the United States, from the effects of de-industrialization on Black and Brown communities to the exploitative labor of the prison-industrial complex.13

Instead, Drew’s artwork emphasizes the materiality of looking, returning us to the complicated conditions of viewership by which the body of the slave was historically brought into view. Fibers and threads push out from its surface, a constant reminder, perhaps, of cotton’s many associations and its hypervisibility in this country’s history. As we read the meaning of the art object through color, composition, and texture, we also read the materiality of cotton itself. In looking at this art object we are also assessing the value of a commodity. The prolonged engagement with surface that Drew allows connects an artwork’s aesthetic value with the market dynamics that underpin conditions of viewership, a subtle critique of the associations of Whiteness, refinement, and connoisseurship within the aestheticized space of the art gallery or museum.

But here, too, in the absence of bodies and the abstraction of this sculpture, we are returned to the conditions that continue to frame American social relations that are the legacy of race-based slavery. This work reveals to me what legal scholar Amy Robinson has argued is “the visual logic of commodity exchange,”14 which has reinforced and continues to sustain the exploitation of Black and Brown bodies in this country. All of which is to say, this artwork materializes a fundamental economic process whereby vision becomes a form of ascribing and assessing social and market value. For as my colleague Eddie Glaude has written, there is a “value gap” in American society: an unacknowledged idea that society values White lives over Black.15 Perhaps, too, in compelling us to reflect on this relationship of vision and value and our own processes of valuation, Drew make these truths self-evident by asking us to consider how artists’, and particularly Black artists’, labor is also continually extracted to bring what is hidden to light.

Another colleague interpreted Number 25 as a form of suffocation: a powerful symbol of the smothering history of racism that has shaped the United States. She described the piece as a kind of historical asphyxiation, materializing Eric Garner and, more recently, George Floyd’s heartbreaking words as they struggled against their murderers: “I can’t breathe.” And indeed, when walking around the sculpture, this sense of suffocation emerges from its materiality: its sheer size and weight is overwhelming; you simply cannot look away from cotton’s terrible histories and the legacies they have produced. The struggle to break the chokehold of White supremacist terror that Drew’s work evoked for my colleague is a powerful reason for studying American art. We are living with the current forms of the lasting regime of American imperialism on which this nation was founded. Understanding and teaching this mitigates against narratives of US exceptionalism that declare America is not imperialist and that are therefore useless for challenging or imagining alternatives to our present. Untangling art history’s involvement in the project of nation building addresses the past to imagine what could have been, in order to sustain what can be.

Cite this article: Anna Arabindan-Kesson “Seeing Empire,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10057.

PDF: Arabindan-Kesson, Seeing Empire

Notes

- Iyko Day, Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism (Durham NC: Duke University Press Books, 2016); Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Harvard University Press, 2001). ↵

- I am grateful to my colleague Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor for conversations that have helped me to clearly articulate this sentence and the ideas in this essay more broadly. ↵

- This work is forthcoming as Black Bodies, White Gold: Art, Cotton and Commerce in the Atlantic World (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021). ↵

- Helen Molesworth, “On Deana Lawson at Sikkema Jenkins,” Artforum, December 2018, https://www.artforum.com/print/201810/helen-molesworth-on-deana-lawson-at-sikkema-jenkins-co-new-york-77713; Roxana Marcoci and Deana Lawson, “Deana Lawson’s Nation,” Museum of Modern Art Magazine, July 19, 2019, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/119. ↵

- Eddie S. Glaude Jr., Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul (New York: Crown Publishers, 2016); Anthony J. Hall and Tony Hall, The American Empire and the Fourth World (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2003); Hardt and Negri, Empire. ↵

- In art history, it is usually the New England wilderness or the expansive vistas of the western frontier that are considered iconic, national, landscapes. Mia L Bagneris and Anna Arabindan-Kesson, “The Spirit of Louisiana: Painting Racialized Geographies in the Slave-Holding Atlantic,” in Inventing Arcadia: Landscape Painting in Louisiana, ed. Katie Pfohl (New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2019), 81–109. ↵

- The painting was probably made for its owner Henry Dorsey Gough, who was “moved” to free some of his slaves while also claiming ownership over others who had freed themselves by running away. For more, see Sean Kief and Jeffrey Smith, Perry Hall Mansion (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013); Max Grivno, Gleanings of Freedom: Free and Slave Labor along the Mason-Dixon Line, 1790–1860 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011). ↵

- Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2013), 153–55. ↵

- Day, Alien Capital, 27–29. Day explains how within settler colonialism, Indigenous populations were subject to a form of elimination (either through absorption or genocide), while African Americans, as alien to the land, became a labor force that was subject to exclusion from the means of social and political control. The hereditary nature of slavery, fused to Blackness, reinforced this exclusion, as did their spatial alienation through the middle passage. ↵

- Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself. {With} Appendix, 6th ed. (London: H. G. Collins, 1851), 7. ↵

- Simon Gikandi, Slavery and the Culture of Taste (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011). Increasingly, these legacies are being excavated, as museums, universities, and other institutions uncover how they have benefited from slavery’s profits. ↵

- I am grateful to Maggie Cao for drawing my attention to this visual connection. ↵

- I am thinking here too of how we live in the “wake” of the plantation, as eloquently described by Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). ↵

- Amy Robinson, “Forms of Appearance of Value: Homer Plessy and the Politics of Privacy,” in Performance and Cultural Politics, ed. Elin Diamond (London: Routledge, 1996), 248. ↵

- Glaude, Democracy in Black. ↵

About the Author(s): Anna Arabindan-Kesson is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art & Archeology at Princeton University