“The Most Perfect Manner”: Paul Weber and the Transnationalism of US Landscapes

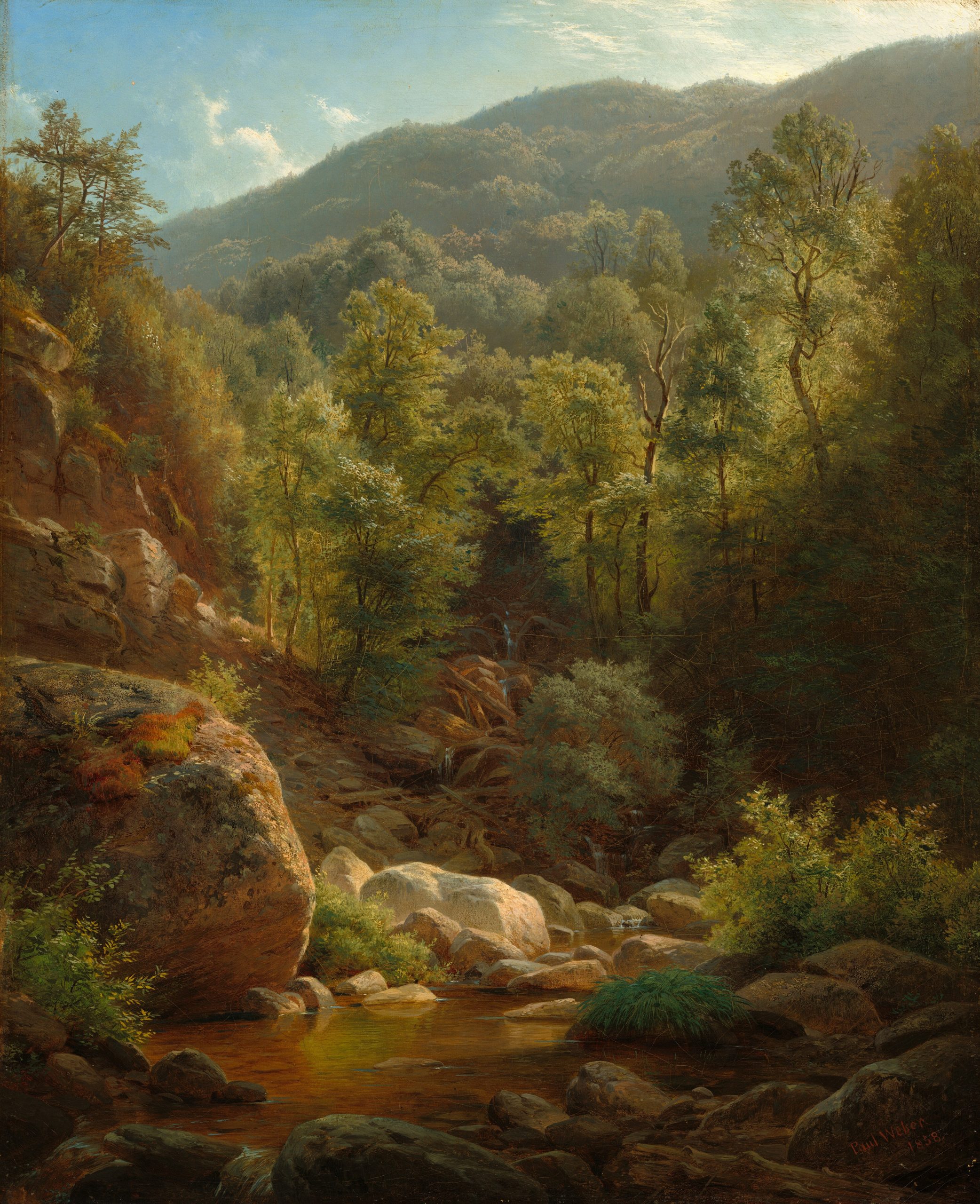

I first laid eyes on Paul Weber’s large Landscape: Evening (1856) during an internship at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in the summer of 2019, as it was being cleaned to feature in the exhibition From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscapes of the Early American Republic, curated by Anna O. Marley (fig. 1). The picture presents an unlocated river scene bathed in the warm glow of what appears to be a summer twilight, framed by crisply painted trees, with mountains stretching into the background. Bearing the aesthetic hallmarks of what would come to be called the Hudson River School, the artist’s presentation of mountain peaks in layers of varying sharpness, as well as the carefully constructed shape of the range, suggest that he was using on-site sketches and observations to render these natural features in detail. His documented travels throughout the American northeast also indicate that he was familiar with US scenery, its features and aesthetic, by the mid-1850s.1 However, it is noteworthy that Weber did not choose to identify the site he figured here, sending it to the academy under the title of Landscape: Sunset (or Composition: Sunset), thus affirming its intentionally generic nature.2 The painting would continue to be referred to as such during the next few years, even after PAFA acquired it for its permanent collection.

From the outset, I was struck that contemporary viewers of Weber’s painting apparently did not mind the vagueness of the image’s relation to the American land it was thought to depict. On the contrary, the picture captured the imagination of amateurs and critics to the point that the artist was hailed as the best living painter of US scenery. Weber was thought to ably capture a quintessential national identity through nature, even if he appeared unwilling to brand his work as a glorification of a strictly American spirit. Though he traveled extensively, Weber actually recomposed most of his landscape scenes in his studio after the fact, where he mobilized sketches and memories to present ideal, reconstructed views of nature.3 A German painter living and working in Philadelphia, by 1856 he had already sent five works to PAFA’s galleries.4 But this scene, in particular, caused a sensation. On May 3, the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin published the first of its laudatory accounts of the canvas:

This [landscape] is a gem among the pieces in the collection. Like most landscapes, . . . it appeals rather to feeling than thought, and this Mr. Weber has carried out in the most perfect manner. . . .The composition presents a wonderful unity, for everything, mountain summits and trees, water and even the lesser foliage. . . . And yet a picture of this description is one of the last which should ever be described, for the emotions which it awakens are the last to which we are wont to give utterance.5

This description indicates that a harmonious, likely imaginary, visual composition mattered more to critics than a definite identification of the site presented. The placelessness of Weber’s view, as such, was no impediment to its praise as a conduit of America’s unique majesty. The sense that Weber had achieved this balance (a “most perfect manner” of sorts) was echoed beyond local sources. In an article published a few weeks later, the New York-based Crayon also acknowledged Weber’s prominence in American landscape painting.6 Despite minor criticism, his success seemed universal. Over the next thirteen years, Landscape: Evening would be displayed no less than fourteen times at PAFA’s temporary exhibitions. However, when the painting made it to one last annual show, in 1870, Weber himself had already left the United States.

Such a narrative puzzled me. Given period concerns about national schools of art, how could one explain the authority critics vested in a German immigrant in matters of American landscape representation during the 1850s? How can we account for the fact that institutions like PAFA considered Weber one of the leading painters of the subject, to the point of purchasing one of his largest works? Why was Weber intent on depicting deliberately vague US geographies at a time when landscape pictures were seen to be expressions of the uniqueness of American nature, in a nationalist way? As such, how did Weber’s art embody a tension between national and transnational identities in the representation of US landscapes, by which mid-nineteenth-century audiences seemed unbothered?

Spurred by Weber’s case, my doctoral research analyzes issues of transnationalism in nineteenth-century visual representations of US landscapes. This project pushes me to interrogate the relationships among art, nature, and national character, both in the United States and Europe, notably by focusing on individuals who advanced what I call a “transatlantic aesthetic of US landscapes.” In my dissertation, I argue that select painters, such as Weber, produced generalized views of US landscapes that included features, compositions, and geographies that both evoked and misrepresented the natural sites they were supposed to depict. These pictures were suitable to be viewed by, sold to, and appropriated by a wide audience on both sides of the pond. I contend that the development of US landscape as a cultural and aesthetic category reveals an “entangled history” of interconnectedness, cooperation, and reciprocity across the Atlantic, reprising here a concept devised by historian Eliga Gould.7

Weber’s background was different from those of native-born US landscape painters of his time. Born in Darmstadt, Germany, on January 19, 1823, he was the son of a local composer. In 1842, Weber enrolled at the Städelschen Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt am Main before, two years later, moving to Munich, a city that became his home base, except during his years in the United States.8 Trained at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, he specialized in landscapes, especially of the Alps. But as they did for thousands of liberal Germans, the failed revolutions of 1848 threw him into exile in the Atlantic World, and the young artist arrived in the United States on October 6.9

Though confronted with examples of the dominant Hudson River School in his new place of residence, Weber retained features of the German Romantic tradition well into his US years, perhaps to prove his skills or to appeal to potential patrons.10 Positive perception of foreign-trained artists in the United States might explain why Weber’s success depended on his mastery of European visual languages. Joseph Sill (1801–1854), a painter-turned-art-dealer and Weber’s principal American patron, especially appreciated work by Europe-trained artists. In 1844, Sill played a major role in establishing the Art-Union of Philadelphia, which was inspired by the example of the New York–based American Art-Union, founded in 1839.11 The Philadelphia Art-Union’s ambitious agenda was repeatedly expressed in reports in which it tried to highlight its national scope.12 It soon boasted members in twenty states, distributed engravings, and commissioned paintings.13

With the help of the Art-Union’s networks and resources, its vice-president, Sill, was equally supportive of non-American artists, whose creations he considered vital to the cultural education of the country. Particularly important to him, as I uncovered, was his relationship to painter Emanuel Leutze (1816–1868), who had been brought to the United States as a child by his German parents. Leutze’s return to Europe in 1841 to train at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf was supported financially by Sill, among other patrons.14 While in Düsseldorf, Leutze continually sent fresh pictures to Philadelphia, where he relied on Sill to act as one of his agents. The dealer ensured that the painter maintained links to the US market and facilitated the transatlantic circulation of Leutze’s creations and constant stylistic exchanges.15

Sill and Weber were introduced on November 28, 1848, a few weeks after the latter and his newlywed spouse, Charlotte Kirschten (1826–1873), had settled in Philadelphia.16 Sill’s account of the afternoon he spent with the painter was recorded in his loquacious ten-volume diary, which I had the opportunity to examine at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. It offers insight into Weber’s background and his situation as a recent immigrant:

In the afternoon I went to see a young German artist named “Weber” who has just arrived in this country and who has travelled through the continent of Europe, Asia Minor, Palestine, Egypt, and has made capital sketches in water colour of scenes and incidents of these various countries. He paints also in oil exceedingly well, and had two pictures (landscapes) on his easel. . . . I was quite interested in him and his works, and with his little German wife, and with his little painting room. For as neither of them could speak much in English, we had to guess each other’s meaning as well as we could, and this added to the interest of the meeting.17

The account reveals Weber’s versatility and adaptability, his facility in different media and techniques, and the breadth of his travels. Yet Sill’s portrait also dwells on Weber’s inability to communicate in his new surroundings, due to a lack of English-language skills. It appears that the painter had to rely on a local figure to promote his art before he could fully comprehend the aesthetic expectations of a foreign audience. Sill’s support, already expressed for other non-American artists, was instrumental in establishing Weber’s reputation in Philadelphia, a fame that endured long after the patron’s sudden death from a stroke in 1854.18

Such patronage, however, cannot fully explain why Weber was consciously engineering a transatlantic vision of landscape in the United States. In my view, building a transnational aesthetic language by combining distinct aesthetic practices shielded him from having to extol the “national” character of the land itself. Though he was probably aware of the implications of landscape for the construction of US identity, Weber acted as a bridge between cultures as well as between an older and an emerging generation of artists. During the nineteenth century, artists and political figures attempted to construct landscape as “a discursive and visual category [that] condenses the dual foundations of national identity—space and time—into a synthetic whole,” in the words of Neil McWilliam.19 The twelve years Weber spent working in Philadelphia coincided with an era of redefinition for landscape painting in the United States, which was faced with growing political sectionalism and nativist/nationalist discourses.20 While Weber’s respect for European visual conventions was an asset in winning the favor of several patrons, his unique treatment of American landscapes helped him assert his originality beyond national considerations. His art stands out as a rejection of both the need for accurate topography and the use of well-known natural landmarks as recognizable allegories of American identity. In other words, Weber relied primarily on his own sensibility to comprehend the scenery of the United States, rather than engaging in a construction of the land’s meaning through culture, which the tug of war between North and South to impose their respective models of society had made more pressing. Although Weber’s landscapes were identified by critics and commentators as “American,” they were mostly devoid of the human figures, particularized human constructions, and other visual allusions that would invite viewers to project themselves into an imagined national space.21

By the second half of the 1850s, Weber had gradually associated himself with the Düsseldorf school of painting.22 This lineage was inconsistent with Weber’s training in Munich. While the Düsseldorf school emphasized detail, sentimentalism, and the use of allegories in landscape representation, Munich-trained artists, led by painter Karl von Piloty (1826–1886), were interested in atmospheric effects and a dramatic use of light and dark.23 The confusion, however, greatly contributed to cementing Weber’s reputation among aspiring American landscapists.24 At only thirty years old, with significant painting experience behind him, he refashioned himself as a teacher, offering lessons to artists such as Edward Moran (1829–1901), a fellow European immigrant from England; the Philadelphia-born Edmund Darch Lewis (1835–1910); and William Stanley Haseltine (1835–1900). Weber’s circle of students also included women such as Harriet Cany Peale (1799–1869), the wife of portraitist Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860), with whom she shared a Philadelphia studio.25 Soon, Harriet Peale adopted the practice of reproducing Weber’s pictures, de facto participating in a transnational dialogue over American landscapes. In 1858, for instance, while Weber exhibited his Scene in the Catskills (fig. 2) at the annual PAFA exhibition, a work later purchased by collector William Wilson Corcoran, Peale completed her own picture of Kaaterskill Clove (fig. 3), which focused on the same upstate New York area. The similarity between the two artists is striking, and the impact each had on the other’s productions is undeniable, expressing their impulse to erase stylistic distinctions between works by a native-born and a foreign artist.

Weber’s most loyal student was William Trost Richards (1833–1905), who was introduced to the German painter in July 1851 at the age of eighteen.26 Weber’s drawing technique and practice of outdoor sketching had a direct impact on his student’s early approach to landscapes, and the two artists traveled together through the northeastern United States. Weber’s teachings also pushed Richards to embark on a trip to Europe in 1855.27 One painting owned by PAFA made during this formative decade illustrates Richards’s debt to Weber. A Mountain Lake (fig. 4), painted during his European tour, offers a broad view of an unspecified mountainous environment. It represents an ideal combination of natural elements as much as an exercise in style, mobilizing both Richards’s experience of US scenery and his recent training at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf to convey a generic idea of European scenery.

Richards’s communication of a romanticized natural experience in the form of a synthesis of European and American landscape traditions—as Weber had illustrated in his Landscape: Evening—resulted in the creation of what I call a “transatlantic aesthetic of US landscapes,” suitable to provoke the admiration of the largest possible audience on both sides of the pond. Such landscapes effectively acted out a visual amalgamation from continent to continent. In that regard, they could embody what art historian Julia Sienkewicz recently theorized as “immigrant landscapes.” Some immigrant artists, whether Europeans in the United States or Americans in Europe, meditated upon their experiences of displacement and exile by producing transnational landscapes. Such was the case of the Virginia watercolors of British architect Benjamin Latrobe, on which Sienkiewicz bases her case study. Images might present the particular features of a new environment while offering allusive associations to other places, often homelands left behind, thus merging real and imagined sites.28 As such, concepts of transatlantic or immigrant landscapes effectively disrupt the national frameworks of art history by situating certain artists in a “third space.” This liminal position has been described by Homi K. Bhabha as a “cutting edge of translation and negotiation,” or a conceptual space in which individuals adopt a critical behavior intended to essentialize cultures and identities.29 In this space artists, in particular, find themselves driven by a dual, paradoxical sense of being both at home and away from home at the same time, which results in hybrid cultural products.30 Painters like Weber and Richards were thus able to refashion new, transatlantic identities.

Weber’s 1850s views—composite and conceived as idealized, transatlantic American landscapes—illustrate such a transnational (or cross-cultural) approach to landscape aesthetics. They are the product of what geographer Tim Cresswell has conceptualized as “constellations of mobility”: historically and geographically specific entanglements of movements, meanings, and practices, more or less structured, that challenge notions of nationality, border, and hierarchy.31 Constellations are a tenet of mobilities studies, which emerged in the 1990s as an interdisciplinary field interested in the importance of relationships between bodies, ideas, and objects through movement. As such, mobilities scholars establish links between social and spatial issues through mobility while challenging the nation-state framework. Evolving fluidly through the Atlantic World, individuals like Weber seem to embody this process. His Hudson River Landscape (fig. 5), completed in 1854 and now owned by the Arnot Art Museum, presents a supposed Hudson River scene, the general arrangement of which parallels his 1856 PAFA landscape. This resemblance indicates the artist’s desire to dissociate the representation from its physical location, thereby divorcing it from its identification with a strictly national territory, so as to employ constructed visual formulas.

In that sense, it is not surprising that Weber continued to produce US views after departing for Europe in May 1860, when he settled back in Munich and effectively disseminated American landscapes in Europe, even if resorting to artistic reconstitution. His 1863 Chestnut Hill near Philadelphia (fig. 6)—its title most likely chosen later by dealers for the canvas—was completed at the height of the American Civil War. It presents, however, an idyllic, pastoral vision of the land. Far from the turmoil of military battles, Weber’s United States remains both a land of wonder in the eyes of European audiences as well as a continuation of the Romantic gaze and an escape from the nationalization of aesthetic discourses. For their part, US landscape artists of the period frequently alluded to the conflict through their works, thus politicizing scenery. In the words of Eleanor Jones Harvey, landscape painting even became a “surrogate for history painting,” answering the desire of (mostly Northern) artists and audiences to make sense of present events.32

In contrast, few paintings by Weber offer hints about contemporary American political discourses; they deliberately remain ambiguous. For instance, his Pennsylvania Landscape (fig. 7), painted in 1862, presents a somewhat anachronistic view. Two figures rowing along a river hearken back to the early days of land exploration by European colonists. Set in an idealized river valley, his picture evokes a mythology of cross-cultural contacts among North American lands in the early nineteenth century, which Weber carried back with him to Europe in the 1860s. Yet Weber’s intentions are unclear. Is he trying to please potential patrons? Is he commenting on expansion and the settlement of North America? Or is the picture a reflection of his own lived experience as a traveler, emigrant, and immigrant in the Atlantic World?

These elements encourage me to see Weber as one of the architects of a transnational circulation and reinterpretation of both European Romanticism and what later would be called the Hudson River School, a term coined by art critics during the 1870s.33 This makes him a profoundly complex figure. Not an American painter, he was nonetheless hailed as one of the most talented landscapists of his time in the United States, and his pictures offered a generic, ideal, and majestic vision of the land. His ethereal and timeless American paintings borrow from many traditions and achieve a specific goal: they produce a tailored landscape without sacrificing the need for outdoor sketching. These principles helped Weber remain largely independent at a time when numerous critics and artists in Europe and the United States, eager to make sense of their own identities, were pushing for the constitution of more definite national aesthetics.34

Opinions diverged about the relationship of art to nation. To quote Worthington Whittredge, whose development as a painter had been transnational itself:

Schools of art are not born like mushrooms in a night. They are the result of the slow accumulation of work done by many men . . . who, in the aggregate, stamp the work of their period. . . . If art in America is ever to receive any distinctive character so that we can speak of an American School of Art, it must come from . . . the close intermingling of the peoples of the earth in our peculiar form of government.35

In mid-nineteenth-century Philadelphia, immigrant painter Paul Weber undoubtedly embodied these aspirations. Eschewing the need to serve national discourses through his art, Weber resisted contemporary social and political inflections in favor of portraying US nature as a poetic refuge for his transatlantic audiences, mirroring his own cross-cultural experience.

Cite this article: Thomas Busciglio-Ritter, “‘The Most Perfect Manner’: Paul Weber and the Transnationalism of US Landscapes,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11664.

PDF: Busciglio-Ritter, The Most Perfect Manner

Notes

- See a list of Weber’s trips in David Patterson McCarthy, “A Great Success: Paul Weber’s Career as a Landscape Painter in Philadelphia, 1848–1860” (MA thesis, University of Delaware, 1988), 90. ↵

- The painting appears as Composition: Sunset in “The Academy of Fine Arts,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin 11, no. 18 (April 30, 1857): 1. Landscape: Sunset is the title under which Weber sent the work to PAFA and the title that appeared in the show’s catalogue. This title is listed as work number 247 in 33rd Annual Exhibition Catalogue, box 1, folder 30, Annual Exhibition Collection, RG.02.06.01, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Dorothy and Kenneth Woodcock Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. ↵

- Susanne Wartenberg, “Bilder aus der Neuen Welt,” in Faszination Fremde: Bilder aus Europa, dem Orient und der Neuen Welt, ed. Katrin Schwarz (Frankfurt am Main: Imhof Verlag, 2013), 110. ↵

- Peter Hastings Falk, ed., The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1807–1870 (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1988), 247. ↵

- “The Academy of Fine Arts, Thirty-third Exhibition, No. II,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin 10, no. 21 (May 3, 1856): 1. ↵

- W. J., “Sketchings,” The Crayon 3, no. 7 (July 1856): 218. ↵

- Eliga H. Gould, “Entangled Histories, Entangled Worlds: The English-Speaking Atlantic as a Spanish Periphery,” American Historical Review 112, no. 3 (June 2007): 764–86. ↵

- Gould, “Entangled Histories,” 10–15. ↵

- Joseph Sill Diaries, vol. 8, 359, Am.1525, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. On German exiles after the 1848 revolutions, see Donelson Hoopes, “The Hudson and the Rhine: Eine historische Perspektive,” in The Hudson and the Rhine, ed. Rolf Andree et al. (Düsseldorf: Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, 1976), 21. ↵

- This observation was the main framework of analysis of Sarah Anne Klapper-Lehman, “Influences of a Country: The Changing Artistic Style of Paul Weber” (MA thesis, Pennsylvania State University at Harrisburg, 2014). ↵

- On this subject, see Rachel Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City: The Rise and Fall of the American Art-Union,” Journal of American History 81, no. 4 (March 1995): 1534–61. ↵

- Art-Union of Philadelphia, Transactions of the Art-Union of Philadelphia for the Year 1848 (Philadelphia: Griggs and Adams, 1848), 42–43. ↵

- Art-Union of Philadelphia, Transactions of the Art-Union of Philadelphia for the Year 1848, 52–54. ↵

- Elizabeth M. Geffen, “Joseph Sill and His Diary,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 94, no. 3 (July 1970): 326. ↵

- Joseph Sill Diaries, vol. 7, 15. ↵

- Wartenberg, “Bilder aus der Neuen Welt,” 109. Records of the German Reformed Church of Philadelphia also indicate that Weber and Kirschten were married there on October 11, 1848, which suggests that the couple had moved to the United States shortly before. See Pennsylvania and New Jersey Church and Town Records (1708–1985), Philadelphia, German Reformed Church, 79, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. ↵

- Joseph Sill Diaries, vol. 8, 359. ↵

- Geffen, “Joseph Sill and His Diary,” 275. ↵

- Neil McWilliam, “Roots: Landscapes of Nationalism in the Long Nineteenth Century,” in A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Art, ed. Michelle Facos (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2018), 286. ↵

- On nationalism and landscape painting in antebellum US art, the classic study remains Angela L. Miller, The Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825–1875 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993). On the involvement of US landscape painting with political nationalism and sectionalism in the 1850s and during the Civil War, see Eleanor Jones Harvey, “Landscapes and the Metaphorical War,” in The Civil War and American Art, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 17–72. For an extension of the discussion beyond the 1860s, see Linda J. Docherty, “A Search for Identity: American Art Criticism and the Concept of the ‘Native School,’ 1876–1893” (PhD diss., Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina, 1985). One of the most thorough academic studies of political nativism in the United States is John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1955). Other notable studies include Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992); and Peter Schrag, Not Fit for Our Society: Immigration and Nativism in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010). ↵

- The canonical study of the construction of the idea of nation, notably through images, is Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso Books, 1983). ↵

- “Sketchings,” The Crayon 4, no. 1 (January 1857): 28. ↵

- On the Munich school, see Eberhard Ruhmer, Die Münchner Schule, 1850–1914 (Munich: Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, 1979); and Christian Fuhrmeister, Hubertus Kohle, and Veerle Thielemans, eds., American Artists in Munich: Artistic Migration and Cultural Exchange Processes (Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2009). On the career of Karl Theodore von Piloty, see Geraldine Norman, Nineteenth-Century Painters and Painting: A Dictionary (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 237; and Reinhold Baumstark and Frank Buttner, eds., Großer Auftritt: Piloty und die Historienmalerei (Munich: DuMont, 2003). ↵

- On this artistic linkage of German painters with Düsseldorf in the United States, see Lynda Joy Sperling, “Northern European Links to Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Painting: The Study of American Artists in Düsseldorf” (PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1985); and Bettina Baumgärtel, ed., The Düsseldorf School of Painting and Its International Influence, 1819–1918 (Düsseldorf: Museum Kunstpalast, 2011). ↵

- Jennifer Krieger and Nancy Siegel, Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School (Catskill, NY: Thomas Cole National Historic Site, 2010), 25. ↵

- William Trost Richards to James Tyndale Mitchell, Philadelphia, July 19, 1851. William Trost Richards Papers, 1848–1920, box 2, folder 1, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. ↵

- Linda S. Ferber, “Never at Fault”: The Drawings of William Trost Richards (Yonkers, NY: Hudson River Museum, 1986), 10. ↵

- Julia A. Sienkewicz, “On Place and Displacement: Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the Immigrant Landscape,” British Art Studies 10 (November 2018), https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-10/look-first/001. See also her larger publication, Epic Landscapes: Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the Art of Watercolor (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2019). ↵

- Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), 38. On the third space theory in relation to culture and place, see also Homi K. Bhabha, “The Third Space: Interview with Homi Bhabha,” in Identity, Community, Culture, Difference, ed. Jonathan Rutherford (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990), 207–21; Edward W. Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996); Pnina Werbner and Tariq Modood, eds., Debating Cultural Hybridity: Multi-Cultural Identities and the Politics of Anti-Racism (London: Zed Books, 1997); Michaela Wolf, “The Third Space in Postcolonial Representation,” in Changing the Terms: Translating in the Postcolonial Era, ed. Sherry Simon and Paul St-Pierre (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2000), 127–46; Denis Linehan and Pyrs Gruffudd, “Unruly Topographies: Unemployment, Citizenship and Land Settlement in Inter‐War Wales,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29, no. 1 (2004): 46–63; Brigid Cohen, “Enigmas of the Third Space: Mingus and Varèse at Greenwich House, 1957,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 71, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 155–211. ↵

- Nikos Papastergiadis, “The Limits of Cultural Translation,” in Over Here: International Perspectives on Art and Culture, ed. Gerardo Mosquera and Jean Fisher (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004), 330–47. ↵

- Tim Cresswell, “Constellations of Mobility.” Paper presented at the “Thinking Through Mobility in the Nineteenth Century” seminar, University of London, 2008. Accessed October 25, 2020, https://www.dcuci.univr.it/documenti/Avviso/all/all181066.pdf. ↵

- Eleanor Jones Harvey, The Civil War and American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 7. ↵

- Kevin J. Avery, “A Historiography of the Hudson River School,” in American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, ed. John K. Howat et al. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 3–20. ↵

- On this subject, see Angela Miller, “Everywhere and Nowhere: The Making of the National Landscape,” American Literary History 4, no. 2 (Summer 1992): 207–29; Miller, “Nationalism as Place and Process: Frederic Church’s New England Scenery,” in The Empire of the Eye, 167–207; Tim Barringer, “The Course of Empires: Landscape and Identity in America and Britain, 1820–1880,” in American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820–1880, ed. Andrew Wilton and Tim Barringer (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 38–65; Anthony Smith, Chosen Peoples: Sacred Sources of National Identity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 138–41; Lloyd Kramer, “The Cultural Construction of Nationalism in Early America,” in Nationalism in Europe and America: Politics, Cultures, and Identities since 1775 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 125–46; Susan-Mary Grant, “Promised Land, Chosen People: The Landscapes and Ligaments of American Nationalism,” Nations & Nationalism 24, no. 2 (2018): 300–11. ↵

- Quoted in Baumgärtel, The Düsseldorf School of Painting and Its International Influence,” 35. ↵

About the Author(s): Thomas Busciglio-Ritter, PhD candidate, Department of Art History, University of Delaware