The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa

ShiPu Wang

ShiPu Wang

University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017; 196 pp.; 39 color illus.; 36 b/w illus.; ISBN: 978-0-271-07773-4; Hardcover: $69.95

Art historian ShiPu Wang opens his new book with a bit of a visual teaser: he provides brief but rich descriptions of four figurative works of art but leaves them unassigned to any artist. Wang quickly reveals that viewers “may be surprised to learn” that the described works were created by four different artists of Asian descent active in the United States during the early twentieth century. Wang assumes our surprise because none of the works evidence “stereotypical notions of Asian imagery, such as landscape or nature paintings done with brush and ink” (1). I venture that readers of Wang’s prior, equally important volume, Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, or his award-winning American Art article, “We Are Scottsboro Boys: Hideo Noda’s Visual Rhetoric of Transracial Solidarity,” which he expanded into chapter three of The Other American Moderns, may not be all that surprised that the artists under consideration are of Asian descent, because Wang, along with such prominent scholars as Anthony W. Lee and Amy Lyford, has already cast away such stereotypes while broadening the categories of American modernism and Americanness.1 But his second assertion, that most readers will be unfamiliar with these four artists, their biographies, and their artistic production, rings true. The four artists under discussion are photographer Frank Sake Matsura (1873–1913) and painters Eitaro Ishigaki (1893–1958), Hideo Benjamin Noda (1908–1939), and Miki Hayakama (1899–1953). Wang’s project is much more than just the recovery and recuperation of four noncanonical artists. In this lavishly illustrated, extremely well-written book, Wang questions the four’s “pictorial strategies in relation to largely unexplored historical, ideological, and personal impetus” (1). Wang’s book is the outcome of many years of archival research, close examination of artworks, and investigative critique of extant text; it is a significant addition to the literature on twentieth-century modernism in the United States.

As Wang discusses in his introduction, and then explores in depth throughout the book’s four chapters, each of the four artists identified with other marginalized people, especially African Americans, and depicted people of color in their artwork, thus creating what he refers to as “imagery of the Other by the Other” (4). Each artist, he continues, was well aware of their own status as a racial “Other” in “exclusionist America”—several artists painted either immediately around the time of the racist Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act), which established the National Origins quotas that entirely excluded Asians from immigrating to the United States, or during the shameful period in American history of Japanese interment (1942 to 1946).

Each chapter is dedicated to a single artist, and Wang begins each with a deep reading of a select work of art. Following up on these rewarding close readings, Wang deftly resituates the work of art within its original cultural, sociopolitical, and ideological contexts. Chapter one opens with a discussion of Frank Sake Matsura’s photograph of himself along with indigenous woman Susan Timento posed in his studio, located in the Pacific Northwestern border town of Okanogan, Washington. Wang describes how Matsura was highly productive, creating twenty-five hundred photographs of Okanogan and its people between 1907 and his early death in 1913 at age thirty-nine. He was mourned by hundreds, eulogized as a beloved and “excellent citizen,” and named one of the most “Useful men in our community” by the local paper, even though he was prevented from obtaining the legal status of US citizen (15–16). This treasured member of the community differed from the working-class residents of Okanogan, Wang tells us, as he came from a Japanese family with considerable financial means. There were other secrets—tragedies experienced at a tender age—that Matsura kept from his community, and which, Wang argues, differentiated him from others in the border town.

Matsura worked as Okanogan’s photographer and accompanied surveyors to capture significant aspects of the development of the region. He also worked as a photojournalist; however, in Wang’s view, the “genre in which Matsura invested most of his creative energy. . . . was portraiture,” as it provided him with a steady income (18). These portraits are fascinating. Trusted by members of local indigenous communities, Matsura photographed Native Americans both on the reservation and back at his studio wearing their best clothes and presenting their best selves. Wang applies the scholarship of Glen Mimura to his discussion of Matsura’s portraits of indigenous people, arguing that they do not conform to the trope of the vanishing Indian.2 Instead, Wang claims that these photographs offer a complex representation of a society in transition and are in stark contrast to the work of Edward S. Curtis and Lee Moorhouse. It was Matsura’s ambivalent position as a local and an outsider, Wang posits, that enabled him to represent the borderlands of Washington state and indigenous Americans differently from other photographers. Matsura, Wang points out, “foregrounds the agency of the model,” creating a give-and-take collaboration between the artist and the models (24). The most intriguing of Matsura’s portraits are those where he joins the sitter in the picture frame, thus complicating the image through his dual role as both the maker and the subject. Interestingly, he inserted himself into the studio portraits of both indigenous Americans and Caucasian Americans, clientele who represented divergent socioeconomic backgrounds. In so doing, Matsura transgressed multiple social borders—including class, race, and gender—within these provocative images.

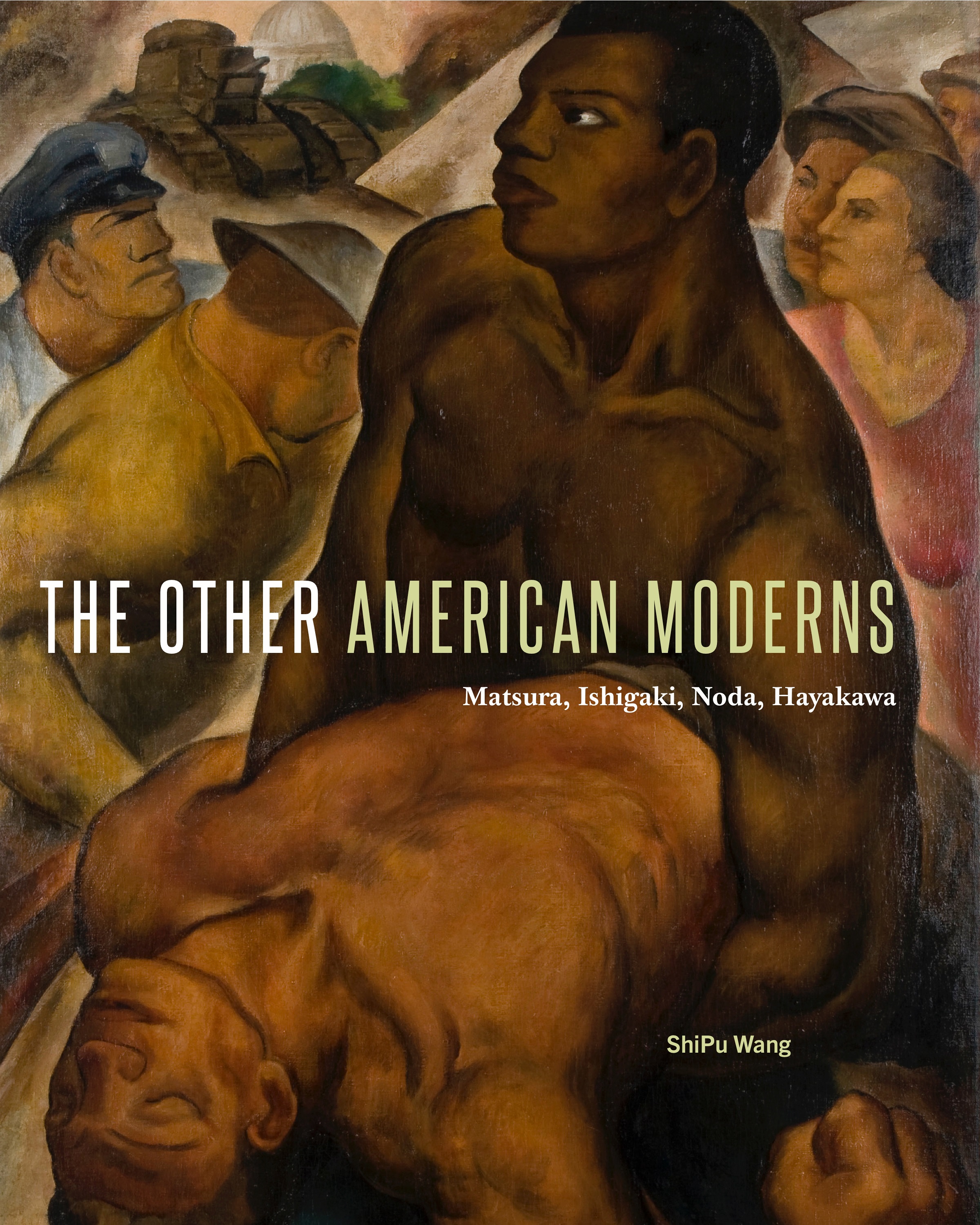

ShiPu Wang’s stirring discussion of Eitaro Ishigaki’s bold painting The Bonus March (1932; The Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, Japan), which depicts a towering African American man carrying the limp figure of what appears to be a Caucasian man over his muscular arm, is the focus of chapter two. Wang’s treatment of this large-scale painting is as commanding and impressive as the actual event and its history. While Ishigaki today is a little-known figure, this was not the case in progressive circles in pre-World War II New York City. The painter was a founding member of the John Reed Club in 1929, a contributor to the New Masses, and active in the anti-fascist American Artists Congress in 1936. What, in Wang’s words, “somewhat” separates Ishigaki’s impressive oeuvre from those of other social realists was his intimate understanding and experience of being a marginalized minority within American society (42). By using “somewhat” Wang acknowledges that a large percentage of social realists within the United States were either ethnic or racial minorities, immigrants or children of immigrants, or women. This chapter marks Wang’s contribution—and a weighty one at that—to the scholarly literature analyzing the long-standing solidarity between Asian Americans and African Americans; however, the inclusion of a small literature review examining this cross-racial affinity, which was complicated and at times ambivalent, would have been helpful. Wang explains that his investigation of Ishigaki’s imagery of African Americans serves to contribute to transracial scholarship. Why the artist chose not to focus specifically on Asian Americans within the United States as his primary subject was left unexplained. Wang goes on to provide a biographical overview of Ishigaki’s life, from his time as an itinerant worker on the Pacific Coast in the 1910s and his associations with radical Asian political and artistic figures, up through his involvement in the 1930s with a series of “free-spirited” women who informed his recurrent depictions of powerful females. Ishigaki’s biography makes for a rewarding read and one that yields a deeper understanding of his work. Wang’s success, however, is in locating the painter’s work within the left, intelligentsia milieu of the late 1920s and 1930s. In this manner, this chapter both alters and greatly expands our knowledge of the 1930s, art and the Left, and social realism.

As with Ishigaki, Hideo Noda focused on the poor and disenfranchised and the conditions of African Americans, both in the city and the rural South. Noda’s paintings, using Wang’s terminology, are examples of the Other creating work of the Other in identification with that group. His Scottsboro Boys (Alabama) (1933; Mizoe Art Gallery, Fukuoka, Japan) is the subject of chapter three. Wang masterfully lays out the details and history of this infamous case of Southern injustice cited in the title. Scottsboro Boys was the young (early twenties) Noda’s first overtly topical work, along with his first work to receive critical attention. Noda painted it in New York City during the depths of the trials down South (75). He was fresh from assisting master Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in San Francisco and New York City—on the California School of Fine Arts The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931) and the destroyed Rockefeller Center fresco, Man at the Crossroads (1933). Many talented artists helped Rivera, and it is most likely at Rockefeller Center that Noda met Ben Shahn. Indeed, Scottsboro Boys shows a strong stylistic awareness of Shahn’s work on prison reform; Shahn likewise was planning a series on the Scottsboro Case. Scottsboro Boys is stylistically curious and relatively obscure, representing several disparate moments of time. In Wang’s view, Ilene Susan Fort’s pioneering work on Social Surrealism is relevant to interpreting the style and composition of the work.3 Wang describes the work as Noda’s engagement in the debates among artists on the Left as to which subject matter and styles would best serve American artists’ dual objectives: “defining modernity in visual terms and effecting social change through art” (77). Noda’s personal history fascinates and helps explain his choice of artistic subjects. Reportedly, the painter was engaged in “underground work” for the Communist Party in 1935 and 1936, working as a Soviet agent. It is within this political context that Wang convincingly maintains that Noda’s painting of the Scottsboro case served to articulate and anticipate “[his] overarching political commitments and alliance with the Left” (91). Instead of just painting injustice, Noda took action, putting his art in the service of politics (89).

Finally, chapter four concentrates of the art of Miki Hayakawa, the least studied of the four artists Wang considers and the only woman. The author opens with a consideration of Hayakawa’s Portrait of a Negro (c. 1926; Los Angeles County Museum of Art) and then modestly presents the first focused analysis and sustained research on the painter, pointing out that most information about her in biographical sketches and surveys is riddled with inaccuracies. We quickly learn that Hayakawa was “as accomplished as many well-known California artists,” receiving critical attention and praise just a few years after she began formal training as an artist (99). Wang explores her art, its reception, and her life within the multiethnic artistic milieu of the Bay Area, of which she was an active member. Her work and story prove a compelling narrative of the ways in which the events of Pearl Harbor and the internment of American citizens and immigrants of Japanese descent had their promising careers disrupted. In approaching this subject, Wang has done the Herculean task of locating more than fifty paintings and drawings made by or attributed to Hayakawa. As he proposes, a book-length study of Hayakawa is now necessary.

In summary, my questions or quibbles are tiny in light of the significant scholarly achievement of Wang’s book. Wang’s work will have wide appeal, including to scholars of American modernism, those interested in the representation of African Americans and Native Americans, and the history of the Left, in the case of Ishigaki and Noda. Extremely well researched and written with a lively touch, Wang’s book will make you rethink the accepted and traditional narratives of early twentieth-century art in the United States, either as you were taught it or as you now teach it.

Cite this article: Diana Linden, review of The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa, by SiPu Wang, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1671.

PDF: Linden, review of The Other American Moderns

- ShiPu Wang, Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (University of Hawai’i Press, 2011); ShiPu Wang, “We Are Scottsboro Boys: Hideo Noda’s Visual Rhetoric of Transracial Solidarity,” American Art 30, no. 1 (Spring 2016); Anthony W. Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); and Amy Lyford, Isamu Noguchi’s Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930–1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013). ↵

- Glen Mimura, “A Dying West? Reimagining the Frontier in Frank Matsura’s Photography, 1903–1913,” in “Alternative Contact: Indigeneity, Globalism, and American Studies,” special issue, American Quarterly 62, no. 3 (September 2010): 687–716. ↵

- See Ilene Susan Fort, “An International Modernist,” in Yun Gee: A Modernist Painter (New York: Marlborough Gallery, 2005) and her article, “American Social Surrealism,” Archives of American Art Journal 22, no. 3 (1982): 8–20. ↵

About the Author(s): Diana Linden is an Independent Art Historian