The Thiele Family Monument: Vision of a Heavenly Future

For over one hundred years a granite lady-angel has stood beside a life-size seated granite businessman while gazing at a carved cherub below (fig. 1). For a century passers-by have pondered this unusual family, immortalized in stone on a Wisconsin cemetery plot. What relation do the two winged figures and the seated man bear to the members of the Thiele family interred around them? What did the carvers and patron/s wish to say with this grand sculptural vision?

Unraveling the story of the Thiele monument provides an avenue into a time in the United States when cemetery monuments held a more significant place in society-at-large than during the century since.1 Few public art museums displayed collections of contemporary sculpture at the turn of the twentieth century, but in the cemetery, fine art fused with popular culture and private sculpture addressed the public. This was also an era when dominant American culture espoused Christianity, with its core message of salvation, resurrection, and eternal life, and the cemetery provided a prime location for the expression in art of hope for life after death. Thus, cemetery sculpture fulfilled multiple essential purposes by expressing identities to be remembered and values to be promoted. For Henry Thiele (1842–1897), a German-American carpet maker and home furnishings dealer in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who served as a trustee in the Zion Church of the Evangelical Association of North America, the most important things in life were Christian faith and family. His wife, Johanna Funk Thiele (1847–1927), filled the roles of Christian helpmate, homemaker, and mother while Henry lived and became family head and breadwinner at his death.

I will argue that the monument memorializes these German Americans by embodying their identities as Evangelical Association Christians whose faith embraced the centrality of family, the potential for spiritual perfection on earth, a domestic ideal of womanhood, and a heavenly family reunion as the ultimate reward. By materializing their personal faith in the form of a large granite sculpture placed on a prominent knoll near the entrance to Milwaukee’s Union Cemetery, they testified to a particular religious and cultural ideal in a final act of evangelism. This case study addresses an often overlooked but important role that many American grave monuments played during the nineteenth century: the attempt to present in visual and permanent form the intangible beliefs and ideas that the deceased held about life after the grave. For Christians of many different denominations, these beliefs formed an important part of the memorialized person’s identity.

Unfortunately, no monument contract, correspondence, or critical responses have come to light, and the exact date of the commission as well as the name/s of specific patron/s remain obscure.2 The family name appears on the monument’s die (the area designated for inscriptions), Henry Thiele’s monogram ornaments the cap, and the maker’s signature “Executed by Lohr & Weifenbach,” graces the bottom base at the rear of the monument. These three minimal texts convey important information, but the primary statement the monument makes is visual. In order to begin to understand the Thiele family, their community, and the roles this sculpture played for both, we must rely on visual and historical analysis of the sculpture in the context of the rural cemetery, the Evangelical Association’s doctrines and practices, Milwaukee’s middle-class German-American culture, and documents related to the Thiele family and to the monument firm.

The Monument

The Thiele memorial is of a type that became popular in the last quarter of the nineteenth century: the family monument. Larger than a headstone and often fairly simple in design, this type of monument usually occupied the center of a family’s plot where it proclaimed their surname. Identities of individual family members appeared on headstones surrounding the central monument. The Thiele monument is more elaborate than many. Its three life-size, full-round figures reinforce the function of this monument type by illustrating a family and, as will become apparent, by incorporating portraits to particularize it.

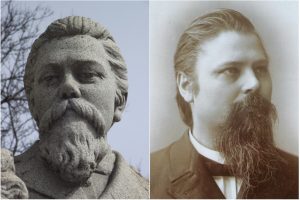

The viewer immediately identifies this figure group—seated man, affectionate woman, naked toddler of indeterminate sex poised to climb into the man’s lap—as a naturalistic family scene. Only the wings suggest a deeper meaning. The sole figure without wings wears a double-breasted frock coat, tall shirt collar, and trousers in the fashion current among businessmen circa 1885–1895. That this figure represents Henry Thiele, an identification suggested by the presence of his monogram beneath, can be demonstrated by comparing a photograph of Thiele with the carved granite face on the monument (fig. 2).

The same swept-back hair, bushy mustache and beard, prominent nose, neat eyebrows, large earlobe, and thick neck characterize both. He is presented not only as a businessman, but as a loving father who reaches his right hand around the back of the toddler as if to boost it into his lap (fig. 3).

Positing an alternative to the stereotype of the detached, authoritarian Victorian-American father, historian Margaret Marsh discerned the emergence by the 1890s of “masculine domesticity,” a new role exhibited primarily through fathers’ increasing interactions with their children.3 This idea is certainly referenced in the monumental family’s intimate interactions.

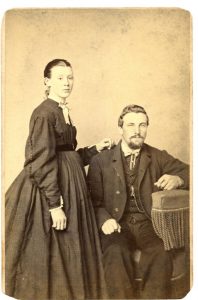

The compositional arrangement of a wife standing with her hand on her seated husband’s chair or shoulder had become a stock pose for photographic portraits of couples during the nineteenth century (fig. 4).4 The sculptor infused it with greater intimacy by placing the woman’s hand on her husband’s far shoulder and adding the child. In addition, he adapted the studio pose to the landscape setting of the cemetery.

Seated on a draped form of indefinite shape that might be taken for a rock, Thiele appears relaxed in the outdoor setting. He died at fifty-four of diabetes, a disease often accompanied by circulatory problems and lameness, so it is quite possible that the seated pose was chosen as the most characteristic. It also suited the emphasis on nature in rural cemeteries, perhaps bringing to contemporary viewers’ minds a family picnic, an activity that often took place in such settings.

But the other two members of the family disrupt the idea of a genre scene. The tiny wings on the toddler’s back identify it as a cherub, a figure commonly seen in late nineteenth-century Victorian American art, and one whose history on grave markers Elizabeth Roark has ably traced.5 Renaissance cherubs, particularly those in Raphael’s Sistine Madonna (fig. 5), who look up to figures in heaven, were very much admired during the Renaissance Revival of the 1890s in the United States.

These particular cherubs were constantly reproduced in oil copies and prints of all types. As art historian David Alan Brown has pointed out, the Sistine Madonna resided in Dresden and had a strong influence on German artists and audiences.6 We may infer that it impacted German-American artists and patrons, such as Lohr & Weifenbach and the Thieles, since the Thiele cherub bears a clear resemblance to those by Raphael (fig. 6).

American audiences easily recognized cherubs as the imps that populated so many heavenly pictures in art, so the presence of this one on the Thiele monument identifies the scene as taking place in heaven, rather than on earth. The cherub stretches its chubby arms up to grasp the man’s left hand and right sleeve in an open-armed embrace, welcoming a new soul to heaven (fig. 7). At the same time, Henry Thiele reaches around the cherub, a man embracing his heavenly destiny.

Although the cherub’s primary function for any visitor to the cemetery who did not know the Thiele family is to locate the scene in heaven, friends and family members could also make a more specific identification of this child angel. The first and last of Henry and Johanna Thiele’s six children died before the age of one. Christoph Henry Thiele died of peritonitis in 1875 at just under six months of age, and pneumonia carried off his brother Bernhard in 1890 about three months before his first birthday.7 as the cause of death.]

There may also have been one stillborn child, the twin of daughter Mary.8 Lacking a discernable sex, the sculpted figure functions as a composite symbol of all the Thiele’s deceased children.

Material culture historian Karin Calvert provides an additional reason for the figure’s sexlessness. She has demonstrated that nineteenth-century parents de-emphasized the sexual identity of very young children, using identical dress, hairstyles, and furniture in order to make them appear androgynous and angelic. She concludes: “Victorian society viewed infants as infants, and saw no need to differentiate baby girls from baby boys.”9 The effort to visually mark infants as a distinct human group characterized by innocence is heightened in the Thiele monument by the baby’s nudity, which symbolizes the vulnerability, innocence, and purity attributed to the very young. Infants and small children were often referred to as angels, an endearment most appropriate, according to many parents, when children slept, another nineteenth-century euphemism for death. In the popular imagination, such young children were often described as becoming angels in heaven upon their deaths.10 A verse in one Evangelical Association hymnal, which may have been sung by the Thiele family states:

Death may the bands of life unloose,

But can’t dissolve my love:

Millions of infant souls compose

The family above.11

The stone infant represents that family above.

Ultimately, the sculptor elided what Roark describes as two separate types in cemetery art, the cherub and the child angel, to create a unique winged figure that simultaneously references the Thiele children who preceded their father in death and the cherubs that inhabit heaven in art.12 Whether interpreted literally or symbolically, the stone cherub provided family and friends with a comforting way to imagine the deceased Henry Thiele—as a father in heaven, playing with a toddler.

The third figure on the sculpture, the angelic adult woman standing in the position of wife and mother, complicates this family portrait. As with the cherub, angel wings should indicate a figure already deceased and awaiting her husband in heaven, but Johanna Thiele was very much alive when Lohr & Weifenbach executed the sculpture sometime between 1899 and 1912.13 The other option—that the figure simply represents the ubiquitous, generic cemetery angel, unconnected to the roles of wife and mother or to the person of Johanna Thiele—is untenable.

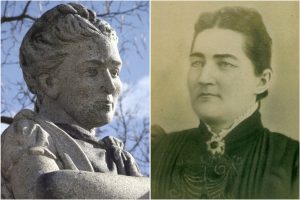

Imported from Italy by the hundreds, mass produced in New England’s stone shops, and found in monument showrooms around the country, turn-of-the-century generic cemetery angels were characterized by classical female features and hairstyles or by androgyny, and they wore classical draperies (fig. 8).14 By contrast, this figure’s strong square jaw, heavy eyebrows, and a turn-of-the-century hairdo, parted in the center, swept back from the sides and brought up into a roll or braid around the crown of her head, indicate a portrait of a specific woman. Her full, floor-length skirt drops from a defined waist in a silhouette easily recognized in advertisements for women’s skirts around 1905 (fig. 9). Somewhat more ambiguous, her shirtwaist consists of short, slightly puffed sleeves with scalloped edges under a kind of shrug, gathered at the shoulders and tied at the neck so that soft folds drape down almost to her waist. Dressmakers frequently draped fabric over the chest in a variety of ways (fig. 10), but these sleeves are most unusual, suggesting that the costume may be a combination of contemporary fashion and artistic imagination. Whatever else may be concluded, this is neither the face nor the costume of a typical cemetery angel.

Right: McCall’s, “Pattern 8865. – Ladies’ One or Two-Piece Umbrella Skirt,” 1905, illustration from McCall’s Magazine, June 1905, p. 794.

Her actions are also unusual for a cemetery angel. Instead of holding a memorial wreath, gazing at the grave, pointing to heaven, or leaning on a cross, she comforts Henry Thiele with an arm around his shoulders. This could be interpreted as a guardian angel kind of gesture, but is not one typically seen in Gilded Age sepulchral sculpture. In combination with the child, her gesture looks more like the loving touch of a wife. Moreover, a photograph of Johanna Thiele displays some similarities with the angel figure (fig. 11). The hairstyle is identical and both the mouth and nose bear a resemblance. The sculptor has been generous, perhaps flattering her with a smaller head, lower forehead, stronger cheekbones, and more delicate features, but if the photograph does not absolutely confirm the identification of the standing woman, neither does it disprove it.

There is no other likely person that the winged figure could portray. The Thieles’ eldest daughter, Mary, had only just turned twenty when Henry died, and would have appeared too young to serve as the model for this angel. Nothing is known about his mother, who may have remained in Germany, but she would likely have been portrayed as an older woman than Henry in order to convey the relationship. Only Johanna was five-and-a-half years younger than Henry, about the age of the angel in comparison with the seated figure. Finally, a strong family tradition has survived that says the monument portrays both Henry and Johanna.15 The weight of evidence falls to this identification.

The vision of a loving heavenly family portrayed in the Thiele monument corresponds to the rise of companionate marriage in the nineteenth century, as well as the Victorian cult of childhood, which placed children as the cherished center of the family. In their comprehensive history of heaven, Colleen McDannell and Bernhard Lang conclude:

The idealization of human love reached such proportions that by the end of the nineteenth century, few Christians would deny that the family served as the foundation of heavenly life. The true Christian merely moved from one loving home to another. Meeting one’s departed family in heaven became a more pressing concern than union with God.16

Although the Thieles may not have gone so far as to replace divine love with human love, they did conceive of heaven as a place of Christian family reunion. They pictured the deceased Henry in this sculpture as if he is just joining the loved ones who have “gone before,” as grave markers typically put it. Christian families consoled one another with the belief that death could not permanently part them. The Evangelical Association funeral service ended with a prayer asking God to “watch over the dust of the departed and assuage the grief of the bereaved by the consolation of the Holy Spirit and the living hope of a happy reunion in eternal life.”17 It is this consolatory heavenly family reunion that the monument depicts.

Johanna Thiele as the “Angel in the House”

The angelic representation of Johanna Thiele demands deeper investigation.18 Designed and executed during her lifetime, it appears to represent an idealized, spiritualized image that would, nevertheless, have been recognizable to her acquaintances as a portrait. I propose that the wings derived from a combination of secular and religious sources, and that their effect was to evoke a popular ideal of womanhood. At the same time that the standing angel represents a specific woman, it also personifies the “angel in the house.”

The “angel in the house” was a phrase adopted from Coventry Patmore’s epic two-volume poem, The Angel in the House (1854, 1856), to describe an already existing stereotype of pure domestic womanhood.19 Patmore based his poetic tribute on his own marriage to his “angel” Emily, and it became very popular, selling two hundred thousand copies in England and the United States by 1897 according to Edmund Gosse, who published a history of the poem in The North American Review that year.20 Most editions originated in England, but three American publishers issued at least thirteen more between the original London publication in 1854 and the end of the century.21

One need never have read the poem, however, to know the term, “angel in the house.” It spread from England throughout western Europe and the Americas, appearing in short stories, poems, sermons, and even an obituary.22 To give just one example, an article titled “The Angel in the House” in the Vermont Christian Messenger of 1869 explained that “the family is God’s institution” and “the Christian wife and mother is the angel of the house, for however important and necessary other agencies are, she is God’s ministering spirit to mould a family for heaven. He has so constituted woman that, other things being equal, her moral power is greater than man’s.”23 This explicitly Christian definition of the “angel in the house” molding a family for heaven seems to describe the scene enacted on the Thiele monument decades later, not because the Thieles ever read Patmore’s rather difficult poetic English, but because the type had become well known in American culture by the 1890s.

Scholars agree that the “angel in the house” was a True Woman, submissive to her husband, attentive to her children, and self-sacrificing in the cause of making the perfect home.24 Her domain was domestic and private. Summarizing this stereotype in the context of motherhood, literary scholar Rita Bode writes:

The domestic Angel emerges as loving, good and pure, always gentle, pious, submissive, and above all, selfless and self-sacrificing. Without troubling about self-identity, she consistently places others, especially her husband and children, first. In the privacy of the home, she creates a haven of peace and benevolence, and a sanctuary from the morally suspect public sphere. She submits to her husband, but her innate female goodness makes her superior to the male sex. She is her home’s moral center, providing guidance and exerting influence on the entire household.25

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the American woman had been placed on a pedestal as an innately spiritual being who would help raise male relatives from a lower moral estate, training new citizens in the perfect home setting. The position of the carved angel-woman above the more earthbound, seated man and the angel-child conveys this attitude toward female spirituality and moral superiority.

If the stone image of Johanna represents an “angel in the house,” it would not be the only instance in which a woman was so described in the context of human death. The 1871 obituary of Mrs. Martha Webster in the Chicago Standard concluded with the observation: “She was one of those who exemplify in what a true and genuine sense the good wife and mother is the light of the home. Patient, tender, thoughtful, loving, the ministering angel of the house—how terribly such an one is missed!”26

Johanna can be identified as the angel in the Thiele house on at least three counts: motherhood, homemaking, and piety. These qualities align with a then common German precept, “Kinder, Küche, Kirche” (children, kitchen, church), as defining women’s proper sphere.27

Johanna bore four children in addition to the babies who died, and she appears to have raised them within the traditions of the Evangelical Association to “honor thy father and thy mother,” one of the Ten Commandments (fig. 12). An important sermon delivered in the Thiele’s home church in 1890 reiterated the commitment of Wisconsin Evangelicals28 to children’s education, noting that “a correct Christian Education is the greatest treasure which parents, teachers and educators can give to the children under their care on their journey of life.” It continued, “The main factors in the education of children are: teaching by example and prayer and no place can these be furnished as effectively as in the Christian Home.”29 The Thieles’ success in executing this mandate may be expressed in the actions of the children, who dutifully helped their mother in the last years of their father’s life.

Henry Thiele’s diabetes must have caused serious health problems by his late forties, when he took his whole family to Germany seeking help from medical specialists there.30 Insulin was not discovered until well after his death, so symptoms developed unchecked in the inexorable progress of the disease. Common complications of advanced diabetes include eye damage or blindness, nerve damage, and foot ailments, all of which would have made it hard for Thiele to handle his business. The children began helping out as soon as they were old enough.31 According to the Milwaukee city directories, the two oldest children, Mary (18) and Amanda (17), began clerking in the store in 1895, two years before their father’s death. In 1896 their sixteen-year-old brother Herman joined them as a clerk, and by the time their father died on February 16, 1897, all four children were working, including fourteen-year-old Henry, Jr. They all still lived at home with their mother, who took over her husband’s role in the Henry Thiele Carpet Company, thereby ensuring continued income for the family. Mary and Amanda became bookkeepers, while Herman and Henry continued as clerks and Johanna held them together as the new head of the business, and of the Thiele household, continuing her mothering role.

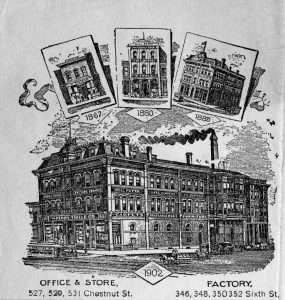

She engaged the second quality of the “angel in the house,” homemaking, in both her domestic and business environments. The family lived on the upper floor of their business in Milwaukee’s second ward, nestled among the Pabst Brewery, Schlitz Brewery, Turner Hall, and the Milwaukee Industrial Exposition building in the heart of the German-American business district. This combination of home and business represents an intersection between public and private spheres that historian Lori Loeb identifies with late nineteenth-century consumerism, and one that helped preserve Johanna’s “angel in the house” identity, despite her business-world functions.32 By the time she took over, the factory, office, store, and residence occupied a three-story brick building at the corner of Fifth and Chestnut streets, with multiple entries on two facades (fig. 13).

Significantly, the family business was the manufacture and sale of such consumer goods as would transform a house into a comfortable home. The Henry Thiele Company made carpets and rugs; retailed curtains, wall paper, picture frames, and window shades; and offered carpet cleaning and refitting, feather dying, and other “interior decorating” services.33 Company advertisements addressed the ladies of this German-American neighborhood, urging them to have their old carpets made into beautiful fluff rugs or their old rags sewn into carpets to make their homes comfortable for their husbands and children. While Henry ran the business, ads in local newspapers stressed the financial gains to be had through weekly sales. “Big Reduction—ten days only—3,800 rolls finest design gilt wall paper, regular price 20¢ and 25¢, now at 10¢ and 15¢ per roll,” ran a typical ad.34 Within a year after Henry’s death and Johanna’s taking the helm, ads began appearing in church publications with a different, more affective approach. “When you get married, buy your carpets, rugs, window shades, wall paper, oil cloths, etc. from the Henry Thiele Co.” ran an advertisement in The Church Times, “the married folks are buying from us every day.” Instead of discounting her regular products, Johanna offered a special deal for couples: “carpets layed and marriage certificates framed free of charge.”35 Not only did she, presumably, make her own home a domestic haven for her husband and children, but she made it possible for other women to do the same for their families.

Johanna’s third “angel in the house” quality, piety, has already been suggested in her other roles as mother and homemaker. In addition, she and her family attended church just four blocks from their home, at Zion Church of the Evangelical Association of North America. This denomination had been founded in the early nineteenth century by Jacob Albright, a German-American Methodist in Pennsylvania who felt called to evangelical mission work among German-speaking immigrants in the United States.36 The denomination spread to Wisconsin, where its first Milwaukee area church was organized in 1846.37 Henry Thiele was born in Steinhude, Germany, near Hanover in 1842 and emigrated to Milwaukee at the age of twenty-four, where he quickly melded into the large German-American community and eventually joined the Evangelical Association. Johanna Funk was born in Wisconsin to parents who had also emigrated from Germany. Her religious affiliation before marriage is unknown.

The Evangelical Association’s “Rules for Members” stressed the importance of marriage between believers and emphasized the role of the family in church life; it encouraged prayer and singing “in the public congregation and the family.”38 Each hymnal contained a section for family worship at home. The Milwaukee Journal reported that the Thieles entertained nearly fifty young members of the church with music, recitations, refreshments, and games in their home.39 This integration of church, home, and family also relates to domestic religion, defined by religious studies scholars as the combination of traditional Christian symbols with Victorian domestic values that crossed denominational lines.40 The monument’s image of a heavenly family, the angelic mother standing at her husband’s side with a supportive hand on his shoulder gazing adoringly at their angel child about to climb into the lap of the paterfamilias, is one that correlates with this late Victorian family ideal and taste for sentimentality as well as with the Evangelical Association’s ideal family.

Other aspects of Evangelical Association theology reinforced the ideal of the angelic wife-mother by focusing on the individual. For example, the doctrine of Entire Sanctification and Christian Perfection, as explained by Bishop J. J. Esher at the 1893 Congress of the Evangelical Association in Chicago, constitutes “the work of the Holy Spirit in the believer, and it consists in the purification from all sin or eradication of all evil affections and desires; . . . Its effect is Christian perfection.” He continued: “It is the calling and privilege of every Christian in this life to be wholly sanctified and without blame before God in love, and thus . . . by faith in Christ he has constant and perfect victory over all temptations and every sin.”41 This doctrine of human perfection on earth applied to both men and women, and brought human beings closer to the realm of the angels. In a longer explanation of Christian Perfection, the Evangelical Association placed the perfected human and the angel in the same category when it cautioned that “the most perfect man, (or angel) will ever be inferior to God.”42

The average parishioner might not know the specific doctrines of their denomination, but Henry and Johanna Thiele certainly did. Henry Thiele was a leader at Zion, the foremost Evangelical Association church in Milwaukee, at a time when controversy over the interpretation of the doctrine of Entire Sanctification and Christian Perfection had led to a national crisis in the denomination.43 Both church papers, the English language Evangelical Messenger and the German Christliche Botschafter carried articles, and lay leaders as well as clergy discussed it. The doctrinal controversy, enlarged by personality conflicts and disagreements about church leadership, raged throughout the 1880s and early 1890s, only ending when the dissenting minority split off in 1894 to form the United Evangelical Church. In 1890, the Wisconsin Conference had met at Zion Church “in an especially serious state of mind” to affirm its unity with the national association’s pro-Perfection stance and to dismiss dissenting ministers.44 The Henry Thiele family, as leaders at Zion during this period, almost certainly embraced the church’s strict position on the doctrine.

The monumental figure of a living Johanna Thiele with wings evokes the American cultural ideal of the “angel in the house,” a secular image rooted in cultural Christianity. Reinforced for the Thieles and their church friends by the German Evangelical Association expectation that the faithful will attain spiritual perfection on earth, the image of the wife-mother-angel figure becomes a role model from both popular and theological perspectives.

The German American Context

In the preceding discussion about this grave marker’s embodiment of a particular family’s identity, and the synthesis of that identity with religious and cultural ideals that emphasized intimate domesticity (placing the father figure in the foreground; elevating the supportive, morally superior wife-mother to angel status; and centering the cherubic infant between them), I have had cause to refer to the family’s German-American ethnicity. I now want to look closer at the specific context of Milwaukee’s German-American community in order to provide a more fine-grained interpretation of the sculpture that takes into account its makers and audience, as well as its subjects.

In 1886 a Milwaukee Sängerfest program reported that the population of Milwaukee included forty thousand Anglo-Americans and twice as many Germans.45 German immigrants and their descendants accounted for the majority of Milwaukee’s population throughout the time the Henry Thiele family lived there, with nearly two-thirds of the city’s population speaking German in the early 1890s.46 It was a comfortable place for a newly arrived German immigrant to begin to adjust.

Historian Kathleen Neils Conzen notes that the diversity among this particular population was so great in the period before 1860 that it included every strata of social class, political persuasions from far left to far right, varied religions (large groups of German Lutherans and German Catholics, with smaller groups of other Protestants and German Jews), and all necessary professions and manufactures.47 Because of this, there was comparatively little pressure to let go of the German language, to search among Yankees for goods or services, or to find social outlets beyond the German-American community. This insularity continued, but waned over the next several decades, and as Paul Woehrmann concludes, “German separatism was not being well maintained by the end of the century. In 1904 the Milwaukee Sentinel editorialized that the German had lost his Germanness but had transformed the larger community.”48 Woehrmann identifies German Lutherans and German Catholics as the primary groups fueling adherence to German language, values, and institutions, while other religious groups “were evangelistic and unionistic, so assimilation came quicker.”49 He also points out that “Americanization was taught in German.”50 If Woehrmann is correct, the Thieles participated in a community that allowed them to retain the conservative values of their German-American denomination, and possibly even continue speaking German at home, while adopting Anglo-American values and ideals, especially those—like the “angel in the house”—that resonated with German-American preferences. This assimilation of Anglo-American and German cultures was especially easy for someone like Johanna, who was born in America.

Within the broader German-American community, patriarchy prevailed and women often pursued a traditional role. In her comparative study of women’s movements, Patricia Herminghouse finds that “most German women in the New World were not particularly active in the feminist cause, in part because the domestic role in maintaining the traditional culture of their ethnic communities weighed more heavily upon women than men . . . Their organizational activity was generally limited to their own (usually conservative) immigrant religious community.”51 Yet if they were not usually activists in political causes, historian Anke Ortlepp still concludes that “German-American women moved beyond the gender role of wife and mother” and Conzen also demonstrates a degree of independence among German women.52 For example, Johanna Thiele maintained her own bank account while her husband was alive, and among the investors in the bank, her balance was among the highest.53 After Henry’s death, she broke his last will and testament by convincing the three men he had named executors of his estate to step aside and successfully petitioning the court to make her the sole executrix in their place.54

Another aspect of German-American women’s lives reported by the Sängerfest program and confirmed as particularly German by Barbara Franzoi in a study of women and industrialization in Germany at the turn of the century, was the commonplace integration of domestic and manufacturing spheres.55 “The peculiar feature of Milwaukee is its factory population, comparative absence of factories, and the prevailing system of taking goods home once a week to be manufactured by the family . . . The neighbors drop in, and work when at liberty, time is saved and wealth accumulated.”56 This description from 1886 probably applied to the Thieles only very early in their business, when Henry made most of his carpets and rugs himself, before he hired workers and expanded into a broader retail business, but it does underscore the German-American community’s acceptance of the combination of manufacture and domesticity for men, women, and children. Former director of German-American studies at the University of Cincinnati, Don Heinrich Holzman, puts it this way: “women were more often to be found on the home front in German-American families, as they worked as an integral part of the family business, shop, or farm. Here the family was viewed as an economic unit, and each member had an important role to fulfill in contributing to the financial success of the family.”57 When it became necessary, Johanna appears to have played a leading role as head of a large public retail and manufacturing concern, pursuing a hammock patent for which her husband had applied two months before his death and petitioning the city council for permission to construct bay windows on her building that would extend over the property line.58 The court record documents many of her other actions in the public arena: advertising and paying debts, handling the store’s stock, and continuing the business during the six years of probate until the estate was finally settled.59

Because of the relative compatibility of German-American women’s domestic and industrial roles, the upper-middle-class economic and social status the Thieles had attained before Johanna took over the business, and the spatial confluence of her home with her business, she did not have to conform entirely to the middle-class Anglo ideal in order for us to understand her granite image as a representation of that ideal. Her angelic portrait looks capable of running the business and her household, too, as she stands with her right hand on her heart as if swearing an oath. Within the German-American context, she fit a feminine ideal that accommodated greater independence, public leadership, and industrial labor as long as it occurred within the family and the church. Within the national context, her visual presentation as an “angel in the house” would help serve to counteract her actual position as a businesswoman and the functional head of household, thereby demonstrating her Americanization.

Monument Makers

Not only the subjects of the sculpture, but also its makers participated in Milwaukee’s German-American culture, contributing to the particular ethnic formulation of the image. It is not clear how the Thieles chose Lohr & Weifenbach to make their monument, but circumstantial evidence suggests a number of possibilities. The silent partner, Jacob Weifenbach (1845–1924), ran a hotel called the Wolf House just one block from Henry Thiele Carpet Company, so they are likely to have known one another from business and neighborhood associations.60 Another partner, Anton M. Lohr (1861–1946), was very active in the Wisconsin Association of Retail Monument Dealers, giving the firm high visibility in professional funerary circles, so a cemetery superintendent or other individual working with the Thieles after Henry’s death might have made the recommendation.61 The third partner, Philip Lohr (1858–1940), had gained a reputation as a carver of religious figures, many of which could be seen at religious institutions and cemeteries in the region and may have caught the Thieles’ attention. Lohr & Weifenbach also advertised in The Church Times, the same Episcopal publication in which Johanna Thiele had advertised earlier.62 There were many possible points of intersection; what is important is that the Thieles chose a German-American family firm in Milwaukee that shared many of their cultural and aesthetic values and some core religious beliefs.

In 1861, five years before Henry Thiele emigrated from Germany, Carl Friedrich and Catherine Lohr emigrated from Weinoldsheim, Hesse Darmstadt, with their nine children—the tenth, Anton, was born three months after arrival in America—and settled northwest of Milwaukee to farm.63 Fifteen years later the oldest brothers, Charles and Gottfried, formed a gravestone business in Milwaukee with their sister Elizabeth’s husband, Jacob Weifenbach, called Charles Lohr & Company Marble Works. Charles developed into a very accomplished sculptor, and one by one, his younger brothers Philip and Anton apprenticed with him, learning to cut, polish, and carve stone. When Gottfried suddenly left in 1880, the original partnership dissolved and the family reorganized itself over the next two years. Philip and Anton soon opened their own monument company, Lohr Brothers Marble & Granite, in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, presumably to remove themselves from direct competition with older brother Charles.64

Philip Lohr had married Jacob Weifenbach’s niece Caroline, tightening the bonds of this German-American family and business network. They joined the Lutheran Church and began a family, only to bury two sons in the Beaver Dam Oakwood Cemetery by 1884.65 Philip or Anton presumably carved the headstone for these children, Jacob Krafto and Jacob Walter Lohr (fig. 14). It provides the first visual evidence that the Lohr brothers shared some ideas about life after death with the Thieles at a deep personal level. The relief carving on the marble depicts a winged child angel pointing the way to heaven as he takes the hand of a mostly naked kneeling boy. The kneeling figure represents both of the Lohrs’ sons, just as the cherub in the Thiele monument stands for at least two of the Thieles’ children. The motif of a standing or flying child angel guiding a child soul to heaven may have originated with Horatio Greenough’s three-dimensional marble Angel and Child (1832, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and it blossomed into many variations in the cemetery. This early example in the Lohr Brothers’ oeuvre represents a personal interpretation of the popular motif in relief.

Around this time, Anton married into a devout Catholic family in Beaver Dam and he and his wife, Johanna Caspary, settled in West Bend where he had opened a branch office of Lohr Brothers.66 They raised their family in the Catholic Church. The brothers’ religious diversity aided their business by extending their network of friends and acquaintances to include German Lutheran and German Catholic congregations, but they also shared some core Christian beliefs with the Evangelical Association Thieles.

By the late 1880s Philip and Anton had moved back to Milwaukee and in 1891 they formed a new monument partnership with Jacob Weifenbach, the Lohr & Weifenbach Company, located near Forest Home Cemetery in South Milwaukee.67 This is the firm that would eventually make the Thiele monument. Within a couple of years they had six apprentices whom they paid from $2.50 to $3.00 per day.68 In 1898, the year after Henry Thiele died, Lohr & Weifenbach employed nine men and still did all of its work by hand.69 The firm was shifting from working primarily in marble to granite, a harder, more permanent stone with increasing national popularity for cemetery use. Lohr & Weifenbach owned a quarry in Wisconsin, but also held interest in a quarry in Barre, Vermont.70 By this time, Philip and Anton Lohr had been in the monument-making industry for twenty years.

Without documentation, the exact interactions among the Lohr brothers and the Thieles in creating the monument cannot be known, yet they certainly collaborated. The phrase “Executed by Lohr & Weifenbach,” instead of the more common practice of simply writing the firm name and city on the monument, raises the possibility that Lohr & Weifenbach did “execute” it, but did not design it. One family legend says that Henry Thiele designed the monument himself.71 He could have sketched an idea, or he could have described a monument design to others who carried out the ideas after his death. He did document his desire for a family monument in the last will and testament that he wrote in 1891, the same year that Philip, Anton, and Jacob founded Lohr & Weifenbach. This was also the year that Henry Thiele decided to take his whole family to Germany. It was an opportunity to show his children the land where he was born and raised, and to visit family members who had not emigrated, as well as to consult doctors in his homeland. In light of these circumstances, making a will was a prudent precaution.

Thiele’s will left everything to his wife and children in one short paragraph, but went on at length to document his wishes in the event that he and his entire family should perish while on their trip. In this circumstance, his very first bequest was the expenditure of ten thousand dollars “for the purchase and erection of a monument on my burying ground on the Union Cemetery in the city of Milwaukee.”72 Ten thousand dollars was a considerable sum at this time, even for a figurative sculpture. It suggests the importance the memorial held for him, as it represented about one-third of his estate and was the largest bequest in his will, followed by slightly smaller sums to Zion Church, its mission churches, and still smaller amounts to charities and individuals, including his employees. We can be certain, then, that Henry Thiele’s family knew he wanted a monument, and it seems likely that they were honoring his wishes in erecting the present sculpture, but it is not known whether he had imagined or communicated any design. This could equally well have been the work of the monument firm.

Both Phillip and Anton were skilled designers and carvers, so either could have taken the lead on the Thiele monument.73 A 1918 trade journal reported that Lohr & Weifenbach “do their own designing and modeling and make a specialty of artistic work.”74 But it was Philip who had gained renown for his stone carvings of Christian figures and the evidence from this work suggests him as the likeliest carver. For example, he carved twelve apostles for St. Stanislaus Church (fig. 15) that exhibit individualized features, a variety of naturalistic hand poses, and well executed draperies. Their location high on the exterior of the building makes it difficult to judge the hand of the carver, but the church figures demonstrate that Philip’s skills were sufficient for the task of the Thiele monument figures.

Another documented example of Philip’s work can be found on the same knoll in Union Cemetery as the Thiele monument, marking the grave of Adolf Koch (fig. 16), who died in 1914. Lohr & Weifenbach used a picture of the A. C. Koch monument with its life-size figure of Memory placing a memorial wreath on a broken column—symbol of a life cut short—to advertise their firm in 1918.75 Identified in the ad as “designed, modeled, and executed by P. J. Lohr in their own work room,” it portrays the more typical classically-draped female in sandals and Grecian hairdo. Philip Lohr’s skill is apparent in the combination of traditional cemetery symbols with individualized features.

Anton Lohr was well known for his leadership in the business realm, especially with regard to marketing and sales, so he may have been the primary contact with the family. The portrait photographs of Henry and Johanna from which the carver worked must have been supplied by Johanna or the children, who would have had some say in the final design as well. All this is necessarily rather speculative, but we can at least conclude that the monument resulted from considerable thought and collaboration between Lohrs and Thieles. The Thiele family’s input ranged from (possibly) the design or concept to the choice of photographs and the amount of financial commitment. The sculptors’ ideas and talents in both design and execution gave it definition. It is more than likely that the Thieles would not have allowed a design that contradicted their theology, so it must reflect something of their ideas about life after death. Finally, the Lohrs shared family and Christian values with the Thieles and the larger German-American community that are also reflected in the monument.

The Cemetery Context

The site of the monument with all of the family burials (fig. 17) is a prominent one on a slight hillcrest inside the front gate of the cemetery, an appropriately visible spot for a sculptural statement of the magnitude of the Thiele monument. However, when Henry died in 1897, he was buried beside his infant sons in his plot at the very north end of Union Cemetery, the one mentioned in his will.76 He and his family had survived the trip to Germany, so the bequest for “a monument on my burying ground,” did not materialize. Cemetery records indicate that Johanna purchased the current, larger plot in a more prominent position near the center of the cemetery and had her husband and sons moved there in June of 1899, two years after Henry’s death.77 This purchase was certainly preparatory to erecting a monument. Cemeteries routinely set aside such advantageous plots for families who would contribute significant sculptural monuments, adding visual interest, cultural status, and sales potential to the cemetery.

Although a private monument, its location gave it a public audience. The Thieles were certainly aware of this when they erected it, therefore we must consider the strong possibility that this evangelical family had evangelistic goals for the sculpture in addition to consolatory and memorial ones.

During the early nineteenth century, the material culture of death had shifted from an earlier focus on the decaying remains of the body and the past earthly life, to a new realization of death as a temporary state between life on earth and life beyond, with emphasis on the life to come. The terms “graveyard” and “burying ground” were gradually replaced by “cemetery,” a word derived from the Greek for “sleeping place,” and the language and imagery of rest—the sleep from which one awakens—began to dominate. This transition into optimism accompanied the invention of the rural cemetery, a beautiful, park-like garden landscape outside the boundaries of the city, where urban families regularly visited already departed family members, picnicked, courted, and relaxed from the pressures of an increasingly modern industrialized life, and where they would retire at death.78 Changes in the physical markers on the graves of the deceased reflect the same shift in focus from death, grief, and mourning to renewed life, particularly for Christian families.

Union Cemetery was formed in 1865 by a union of three churches, St. Johannes Lutheran, Trinity Lutheran, and Grace Lutheran. It began as St. John Cemetery with forty-one acres along Teutonia Avenue in Northwest Milwaukee, but expanded northward to cover one hundred acres of wooded rolling hills with winding paths laid out to provide picturesque rambles by the time Henry owned land there. At the same time, it expanded from a German Lutheran clientele to become a broader community cemetery, although the precise religious and class demography of its lot owners, as well as any rules regulating the space at the turn of the century, are now unknown. We can at least be sure that those many Protestants, such as Henry Thiele, who purchased lots in the cemetery were willing to make the two or three-mile pilgrimage from downtown Milwaukee to visit loved ones. Funeral attendees of all kinds joined the lot owners to form one part of the audience for the memorial.

Historians have long known that rural cemeteries were used for recreation and even tourism from the time they first appeared in the United States in the 1830s through their heyday in the 1860s and 1870s, before city parks came into fashion. In the Midwest, rural park cemeteries often remained fashionable destinations much longer. Most rural cemeteries published a prospectus, citing the natural beauties of their landscape and the chapels and other romantic structures ornamenting it as a healthful retreat for urban dwellers in the increasingly industrialized and polluted cities. Many of the largest also published guidebooks so that visitors could find the graves of important local personages and striking monuments. In a classic study of nineteenth-century cemetery use, Blanche Linden-Ward notes that gatekeepers at Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery counted up to 160,000 visitors annually through the 1870s.79 Unfortunately, such records were not kept for Union Cemetery, but even as late as 1899 when the national use of rural cemeteries as parks was waning, Union remained an active recreation spot, and these tourists and leisure visitors formed another part of its audience.

Milwaukee did not establish a park commission until 1889, and when it finally began the serious business of developing city parks, a long history of prioritizing industrial urban growth made it “almost impossible to procure suitable property in many parts of the city,” as one board member recalled.80 Apart from cemeteries, one of the only provisions for outdoor recreation was the German beer garden.81 Milwaukee’s several beer gardens, including Pabst and Schlitz in the northwest region of the city, invited recreation through alcohol consumption, group singing and dancing, concerts, games, and other community socializing that encouraged many people to congregate in a relatively small space. They also usually charged admission, thereby limiting access to those who could afford such recreation.

Union Cemetery, by contrast, afforded quieter, more pastoral surroundings in which to stroll, ride a horse, consume a picnic, or read a book. It provided an alternative for those who may not have desired the beer garden atmosphere. By 1899, residences surrounded this cemetery, inviting local pedestrians to treat it as a neighborhood park, but since it was by far the largest green space in all of Northwest Milwaukee, it also continued to provide access to nature and fresh air for urbanites from the larger region.82 Thus, large numbers of people regularly visited Union Cemetery, including both Protestants coming to bury or visit deceased relatives, and people of all and no religious persuasion seeking health and recreation. Almost the first thing they saw upon entering the front gates was Henry Thiele’s heavenly family.

In a study of Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, religious studies scholar Colleen McDannell argues persuasively for understanding the mid-nineteenth-century rural cemetery “as a repository for Christian sentiments and values” where “the families who purchased funeral sculpture asserted the inherent sacredness of the cemetery.”83 Images of angels and crosses, and allegories of Hope and Faith are just some of the Christian symbols commonly found in these cemeteries, whether or not they were founded by churches. Linden-Ward notes that ministers and religious liberals argued “that pastoral cemeteries served as schools of moral philosophy and catalysts for civic virtue” where the young in particular should go “to learn from the exemplary lives of notables interred there and to be sobered by thoughts of the shortness of life,” returning home “with new resolve to work hard and to do good.”84 The strategic location of the Thiele monument, the choice of one of the most prominent German-American sculptors of religious figures in the city, and the scale and quality of the resulting sculpture all suggest an intention to broadcast faith in heaven as a postmortem destination. Implicit in the image of Henry Thiele’s happy posthumous home is an invitation for others to follow his example.

The Thieles’ evangelical theology urged them to spread the good news of Christian salvation and eternal life. A history of the Evangelical Association written at this time explained:

. . . the Evangelical Association has been actuated by the spirit of apostolic evangelism . . . . The genius of our church is to be evangelical in doctrine, evangelistic in method, connectional in polity. It is distinctively a missionary church, always pushing out into the regions beyond. Its mission to the world is to preach the living gospel by a living ministry.85

During his lifetime, Henry Thiele pursued mission work as a trustee of Zion Church and, according to one obituary, as the president of the board of trustees for his last years on earth.86 He bequeathed a total of $12,250 to Evangelical Association churches and their poor to help continue this work. He may also have designed or described this monument to communicate his belief in the saving grace of God, whose sacrifice of his son Jesus made eternal life in heaven possible for sinful mortals. Johanna and/or the children exercised their missionary zeal by commissioning the sculptural group after Henry’s death as a statement of faith in life after death that serves not only memorializing and consolatory functions, but also an evangelical ambition. With image rather than words, it says that life goes on in celestial family bliss for those who trust in Jesus as the messiah.

In considering the rural cemetery context of the Thiele monument, we must be conscious of the physical reality of bodily death and decay that the grave asserts and the cumulative emotional effect of hundreds of human graves, many belonging to people early viewers had known. The monument sits in the middle of a large plot where the bodies of Henry and Johanna, their sons Christoph, Herman, and Bernard, and their daughter Amanda and grandson Henry E. Thiele lie buried. An evangelical hymn describes such a cemetery plot and its evangelizing purpose:

Beneath our feet, and o’er our head, Is equal warning given;

Beneath us lie the countless dead, Above us is the heaven.

Their names are graven on the stone, Their bones are in the clay,

And, ere another day is done, Ourselves may be as they.87

The visitor to the Thiele plot reads the names graven on individual headstones and contemplates the “countless dead” buried in the clay below, then looks up at the heavenly family of Henry Thiele carved in granite. The monumental image counteracts the finality of death and encourages passersby who consider their own approaching fate to seek the means of gaining the happy result predicted in this sculpture.

Another marker on the Thiele plot, waiting for great-grandson Timothy Earl Thiele and his wife Nancy, complements the older sculpture. It carries an epitaph that could describe the family’s motto: “Heaven is my Home.”

Conclusion

By the late nineteenth century, many individuals and families erected memorials on their gravesites that helped them cope with death by expressing faith that their lives would continue after death, albeit in a new form. In her book, Beyond Grief, art historian Cynthia Mills explored four “fine art” cemetery monuments and the ways in which their patrons and makers used them to cope with grief. In choosing memorials for upper-class individuals by famous artists—an elite society that could afford the most aesthetically sophisticated monuments—Mills astutely recognized that the best monuments often became a tribute to the sculptor rather than the deceased, a work of art rather than a memorial.88 That was not the case for the majority of middle-class Americans who chose grave markers within their financial means, the best of which represent a class of grave sculpture carved by local artists whose renown extended no farther than their own communities. As a case study, the Thiele monument is an exceptionally good example within this class; the quality of carving and originality of design, as well as the financial commitment of its patrons, set it apart. Yet however aesthetically appealing, its purpose remains memorial, consolatory, didactic, and evangelistic. The subjects have not been overtaken by the carver-artists. Made by a local monument firm for a local audience, it represents the type of fine quality sculpture that was arguably best known and most accessible to the majority of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Americans and which may have held the most significance for them. Milwaukee did not get a permanent art gallery until 1888, and it began with thirty-six paintings but no sculpture. Cemetery sculpture had a strong impact because it was so personal and it was laden with history and emotion.

Lohr & Weifenbach created a sculpture to mark forever the earthly place of the Thiele family’s bodily remains by choosing a heavy, dense material that would withstand weather and the test of time. They gave two of the three figures wings that visually negate the gravity-bound mass and lift viewers’ thoughts to a spiritual level through the well-known symbols of cherub and angel. By adding the features of Johanna and Henry to the adult figures and composing the group in an intimate family interaction, they succeeded in embodying their subjects’ personal identities as German-American Evangelical Association Christians who believed that spiritual perfection can be attained on earth, that religion is lived in the domestic sphere, that the family is the building block of Christian life, and that a reunion in heaven is their ultimate destination. The monument memorializes this family by highlighting the two things to which they devoted their lives, family and faith, in a statement of religious identity calculated to communicate with their public audience. As such, it stands as an excellent example of an important type in late nineteenth-century American cemetery art, a material statement of individualized faith in life after death.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was made possible by a Faculty Research Fund grant from the University of Denver and by the hospitality of Huldah Jean Pierce and the Philip Pierce family who put me up while I traveled around southern Wisconsin. I am grateful to the Newberry Scholl Center American Art and Visual Culture Seminar and its participants in October 2015, especially Erika Doss and Sarah Burns, and to the Cemeteries and Gravemarkers section of the 2016 American Culture Association meeting, as well as anonymous readers, for all their shared insights. I thank the staff at the many cemeteries, libraries, archives, and historical societies who aided this project, especially Peggy Keeran at DU, Graeme Reid and Erika Petterson at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend and Bill Hoffman at Graceland Cemetery. My most profound gratitude goes to Tim and Nancy Thiele, whose generous sharing of family information and successful search for photographs of Henry and Johanna greatly enriched this article.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1579

PDF: Stott Thiele Family Monument

Notes

- A death “industry” coalesced and professionalized in the late nineteenth century, allowing twentieth-century Americans to separate themselves from active participation with corpses, graves, and cemeteries beyond the immediate necessity of burial and commemoration. Cemeteries ceased to function as parks and social centers, and gravestones went from vertical, often sculptural monuments to predominantly low markers with simple inscriptions and minimal carving. New technologies in the twenty-first century have brought more attention to pictorial tombstones once again. On changing cemetery culture, see Kenneth T. Jackson and Camilo Jose Vergara, Silent Cities: the Evolution of the American Cemetery (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1989) and David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991). See also James J. Farrell, Inventing the American Way of Death, 1830–1920 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980) and David E. Stannard, Death in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1975). ↵

- Johanna Thiele may be the likeliest patron, as explained later in this article, because she purchased the plot, but there is no record of the monument expense in the (possibly incomplete) probate account that closed in 1903, so the monument may have come later. By 1903 the children ranged in age from twenty to twenty-seven and should be considered as potential patrons of a sculpture that features both parents. ↵

- Margaret Marsh, “Suburban Men and Masculine Domesticity, 1870–1915,” in Meanings for Manhood: Constructions of Masculinity in Victorian America, eds. Mark C. Carnes and Clyde Griffen (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 111–27. Much of what she says about suburban men was also true for some urban men. For more traditional views of masculinity, see for example Peter Filene, Him/Her/Self: Sex Roles in Modern America (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), 77–88, and E. Anthony Rotundo, American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era (New York: Basic Books, 1993). Gail Bederman stresses the changing nature of masculinity at the turn of the century in Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995). ↵

- The reverse, seated woman and standing man, is also fairly common. ↵

- Elizabeth L. Roark, “Embodying Immortality: Angels in America’s Rural Cemeteries, 1850–1900,” Markers 24 (2007): 63–66. ↵

- David Alan Brown, Raphael and America (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1983), 27–28. ↵

- Bernhard’s headstone indicates that he lived from July 23, 1888, to April 14, 1889, but the Union Cemetery burial book, stored at Graceland Cemetery, Milwaukee, records his death as April 14, 1890, and his age at death as nine months. In either case, he was young. The entry for Christoph gives “perstonitis” [sic ↵

- Tim and Nancy Thiele kindly provided me with a family tree that includes this unnamed twin, whose sex is not known; no death certificate has been located. ↵

- Karin Calvert, Children in the House: The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600–1900 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992), 98. See also Holly Pyne Connor, Angels and Tomboys: Girlhood in Nineteenth-Century American Art (San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2012), 29. ↵

- For more on the nineteenth-century cult of childhood and child death, see Laurence Lerner, Angels and Absences: Child Deaths in the Nineteenth Century (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1997) and Linda Pollock, A Lasting Relationship: Parents and Children Over Three Centuries (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 1987). ↵

- Hymns Selected from Various Authors for the Use of the Evangelical Association and All Lovers of Pious Devotion, 4th ed. (New Berlin, PA: J. C. Reisner, 1846), hymn 439. ↵

- Roark, “Embodying Immortality,” 99–102, discusses child angels as generic types that mimic the activities of adult angels: gaze at graves, drop flowers, pray, or record names. ↵

- In 1924, Lohr & Weifenbach changed its name to Lohr Granite Company, so this is the last possible date for the monument. Johanna did not die until 1927. Most evidence points to an earlier creation date in the range of 1899 to 1912. ↵

- I use the term “generic” to distinguish these common angels from angels named in sacred texts, such as the Biblical Gabriel or the Book of Mormon’s Moroni, who were usually depicted in cemeteries as classically draped males and carried attributes like trumpets. ↵

- Tim and Nancy Thiele, conversation with author, May 16, 2016. ↵

- Colleen McDannell and Bernhard Lang, Heaven: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 228–29. ↵

- The Doctrines and Discipline of the Evangelical Association (Cleveland: Publishing House of the Evangelical Association, 1905), 105–6. ↵

- Of course, it could simply personify a pet name, although if she was called “angel” by the husband who designated her “beloved wife” in his will, that nickname has been lost to history. Henry Thiele, Last Will and Testament, May 30, 1891, Milwaukee County Probate Record No.12298, Milwaukee County Courthouse, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. ↵

- Brenda R. Weber, “Situating the Exceptional Woman,” Nineteenth Century Gender Studies 5 (Spring 2009), http://www.ncgsjournal.com/issue51/weber.htm , accessed December 14, 2016. ↵

- Edmund Gosse, “The History of a Poem,” The North American Review 164 (March 1, 1897): 283. Coincidentally, this essay appeared only weeks after Henry Thiele died. I am not suggesting that one of the Thieles read it, but that as Gosse claimed, after about 1879 sales of Angel in the House “rose to heights unknown in the days of its early success” (293); so it is likely that the phrase and the stereotype it represented were known in Milwaukee, too. ↵

- According to WorldCat, Ticknor and Fields of Boston released the first American edition of volume one, The Angel in the House: The Betrothal, in 1856, followed by more editions as separate volumes and in combination. E. P. Dutton and Company (1876) and Cassell & Company (1887, 1889) of New York were the other American publishers. http://www.worldcat.org/search?q=au%3Apatmore%2C+coventry+ti%3AAngel+in+the+House&qt=advanced&dblist=638 ↵

- See, for example, Catherine Jagoe’s in-depth exploration of the Spanish version of this stereotype, ángel del hogar (angel in the house), in Ambiguous Angels: Gender in the Novels of Galdós (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), which references the English, French, and American versions. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft0z09n7kg/ . Unfortunately, a comparable scholarly study does not exist for Germany, and it is not clear whether German speakers commonly used the word engel (angel) or hausengel (angel of the house) to describe their version of this domestic ideal. See note 28 for the obituary. ↵

- Northern, “The Angel in the House,” (Montpellier) Vermont Christian Messenger, vol. 23, no. 1 (January 7, 1869), 1. America’s Historical Newspapers (SQN: 15FD52860E5D3730). ↵

- The phrase sometimes occurred in relation to children. An anonymous poem titled “The Angels of the House” first identified “The angel of the happy home, / The faithful, trusting wife,” but ended by asserting “there are angels on the earth,/Pure, innocent, and mild, / The angels of our hearts and homes, / Each loved and loving child.” Granville (VT) World’s Paper, August 25, 1860, 5. America’s Historical Newspapers (SQN: 15BEAD09787FAB38). Likewise, a short inspirational story described a careless girl becoming “a gentle follower of Christ, and, as her mother often said, ‘An angel in the house.’” “The Young People,” Tennessee Methodist, August 6, 1896, 6. Nineteenth Century Collections Online (GALE|EKSVLU978098561). In this case, the child is growing toward the ideal for her adulthood. ↵

- Rita Bode, “Angel in the House,” in Encyclopedia of Motherhood (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2010), doi 10.4135/9781412979276.n25 ↵

- “Died. Webster,” Chicago Standard, April 27, 1871, 6. ↵

- According to Wikipedia, this slogan began to appear in the 1890s, but was not widely disseminated until World War II. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinder,_Küche,_Kirche It derived from earlier lists, such as one attributed to the Emperor of Germany and his wife by the anonymous author of “The American Lady and the Kaiser: the Empress’s Four K’s,” Westminster Gazette (August 17, 1899), 6, which added Kleider (clothing) to Kinder, Küche, Kirche. ↵

- I refer here, and throughout this article, to the Evangelical Association of North America, a very specific denomination of German Americans who in 1890 had a synod in Wisconsin. I am not using the term Evangelical in its twenty-first-century, cross-denominational sense. ↵

- Gustav Fritsche, comp., The Evangelical Association in Wisconsin: The First Eighty Years, 1840–1920, trans. Lillian E. Reichert (Wisconsin Conference, n.d.), 188. ↵

- Application for a United States Passport No. 28499, granted June 1, 1891, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC, Ancestry Library Edition. “Local Personal Notes,” Milwaukee Journal, June 2, 1891, 3, and September 26, 1891, 7. ↵

- As historians Mintz and Kellogg have noted in their study of working-class immigrant families, putting children to work was a common economic strategy that subordinated individual desire to family need. Steven Mintz and Susan Kellogg, Domestic Revolutions: A Social History of American Family Life (New York: Free Press, 1988), 88–91. ↵

- Lori Anne Loeb, Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Women (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 129. Although based on British examples, her conclusions also apply to Anglo-America. ↵

- Henry became one of the original incorporators of the Wisconsin Furniture Company. “New Furniture Company,” Milwaukee Journal, March 9, 1894, 3, and March 29, 1894, 2. It is not clear whether he ever sold furniture. ↵

- Milwaukee Sentinel, May 14, 1893, 15. Weekly ads in this paper, from 1891 to 1893, are each a bit different. ↵

- Henry Thiele Company advertisement, The Church Times, official organ of the (Episcopal) Diocese of Milwaukee, vol. 8, no. 6 (February 1898): 3. ↵

- For church history, see Fritsche, The Evangelical Association in Wisconsin. ↵

- Named Zion Church, it was located in Greenfield, Wisconsin, south of Milwaukee. Later, another Zion Church was established by the same denomination in downtown Milwaukee and it is this latter church that Thiele joined. ↵

- Doctrines and Discipline, 20–22. ↵

- “Zion’s Church Entertainment,” Milwaukee Journal, November 17, 1895, 10. ↵

- Colleen McDannell, The Christian Home in Victorian America, 1840–1900 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986) made an early argument for recognizing domestic religion. The “angel in the house” or Victorian ideal of the wife-mother fits into this domestic religion. ↵

- J. J. Esher, “Part II, Chapter 3, A Brief Statement of the Doctrine of the Evangelical Association,” in The Congress of the Evangelical Association: A Complete Edition of the Papers Presented at Its Sessions held at The Art Institute of Chicago September 19–21, 1893, ed. Rev. G.C. Knobel (Cleveland: Thomas & Mattill, 1894), 101–2. ↵

- Doctrines and Discipline, 11. What Evangelical Association literature has survived is text heavy and image light, so I do not know whether a visual image of an angel was ever applied by the church to this doctrine. ↵

- Although it is uncertain when Thiele became a trustee of Zion, his obituaries document that position (see note 88) and he left substantial bequests to all of Zion’s mission churches, demonstrating a position of leadership locally; Thiele, Last Will and Testament. The official interpretation of the doctrine was challenged as early as 1860, according to one account of the controversy, and became a personal and political struggle for control among ministers and bishops that played out across decades, expanding well beyond doctrinal matters. For a history, see Bishop Thomas Bowman, Historical Review of the Disturbance in the Evangelical Association (Cleveland: Thomas & Mattill, 1894), including page 4 for the earliest “heresy” in 1860. ↵

- Fritsche, The Evangelical Association in Wisconsin, 186–87. ↵

- A Souvenir of the 24th Sängerfest of the N.-A. Sängerbund (Milwaukee: Caspar & Zahn, 1886), 75. These characteristic German singing societies formed an important part of Milwaukee social life. ↵

- Victor Greene, “Dealing with Diversity: Milwaukee’s Multiethnic Festivals and Urban Identity, 1840–1940,” Journal of Urban History vol. 31, no. 6 (September 2005): 824. ↵

- Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836–1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976). ↵

- Paul Woehrmann, “Milwaukee German Immigrant Values: An Essay,” in Milwaukee Stories (Marquette University Press, 2004), 222. Reprinted from MiIwaukee History (Autumn 1987). Woehrmann opines that the Sentinel overestimated the rate of assimilation. ↵

- Ibid., 216. ↵

- Ibid., 221. See also Greene, Dealing with Diversity, 820–49. ↵

- Patricia Herminghouse, “’Sisters Arise!’: The Intersections of Nineteenth-Century German and American Feminist Movements,” in The German-American Encounter: Conflict and Cooperation between Two Cultures, 1800–2000, eds. Frank Trommler and Elliott Shore (New York: Berghahn Books, 2001), 53. ↵

- Anke Ortlepp, “German-American Women’s Clubs: Constructing Women’s Roles and Ethnic Identity,” Amerikastudien/American Studies vol. 48, no. 3 (Winter 2003): 425; Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836–1860, 190–91. ↵

- “Plankinton Bank Depositors,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 6, 1893, 9. With a balance of $1,686.50, she was among the top three or four depositors listed when the bank failed. ↵

- “Petition for Letters of Special Administration,” March 9, 1897, and “Letters,” May 7, 1897, Henry Thiele Probate Record, No. 12298, Milwaukee County Courthouse. ↵

- Barbara Franzoi argues in At the Very Least She Pays the Rent: Women and German Industrialization, 1871–1914 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985) that in Germany, women maintained their domestic roles, entering factories only when not in conflict with home duties and with men’s labor, but that by bringing certain types of manufacture into the home, women’s industrial labor became more manageable. This system seems to have been transplanted to Milwaukee, where the strength of the German-American community made it possible to maintain many aspects of ethnic culture. ↵

- A Souvenir of the 24th Sängerfest of the N.-A. Sängerbund, 75. ↵

- Don Heinrich Tolzmann, The German-American Experience (Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2000), 233. He also notes that children commonly worked at an early age, child labor being acceptable to German Americans in the context of the family. ↵

- United States Patent Office, Letters Patent No. 597,227, “Hammock,” January 11, 1898, was Henry Thiele’s fourth U.S. patent related to carpet weaving. https://www.google.com/patents/US597227 Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Milwaukee for the Year 1903 (Milwaukee: Edw. Keogh Press, 1903), 100. ↵

- “Final Account of Johanna Thiele as Administratrix, with the will annexed of the estate of Henry Thiele,” lists eleven months of business expenses, Henry Thiele Probate Record No. 12298, Milwaukee County Courthouse. ↵

- See Milwaukee city directories and Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1891–1910. ↵

- Anton served on the finance committee and Philip was vice president of the Wisconsin Marble-Workers union in 1891 (“Marble Workers Elect Officers,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 10, 1891, 3), but by 1905, Anton had become more active than his brother in such professional organizations. As a director of the Wisconsin Retail Granite and Marble Dealers’ Association, he gave speeches at its annual conventions in 1905 and 1906 and was its president in 1907 and 1908. See “Summer Annual Meeting of the Wisconsin Retail Granite and Marble Dealers’ Association,” Granite, Marble and Bronze vol. 15, no. 9 (September 1905): 25–28, and similar articles in the same journal, vol. 17, no. 3 (March 1907): 15–18 and vol. 18, no. 3 (March 1908): 15–18. Other articles appeared in The Reporter and Rock Products. http://quarriesandbeyond.org/cemeteries_and_monumental_art/monumental_magazines_available_online_list.html#granite_granite ↵

- “Lohr & Weifenbach, Sculpturers and Manufacturers,” advertisement, The Church Times 24 (September 1913): 14. ↵

- The following history of the Lohrs is based on Milwaukee city directories; documents in the Wisconsin Pre-1907 Vital Records Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society Library, Madison; Peter C. Merrill, comp., German-American Artists in Early Milwaukee: A Biographical Dictionary (Madison WI: Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies at University of Wisconsin, 1997), xvii, 64–66; “Anton Lohr, over 80, Is Making Monuments,” Milwaukee Journal, April 5, 1942; the Wisconsin State Census of 1895; and the 1870, 1880, 1900 and 1910 U.S. census records, Ancestry Library Edition. ↵

- Souvenir Program and Centennial History, Beaver Dam, Wisconsin July 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, 1941 (Beaver Dam: Historical Committee of Beaver Dam Centennial, Inc., 1941), 125–26. ↵

- First Lutheran Church, baptismal and death records for Jacob Krafto and Jacob Walter Lohr, in “U.S., Evangelical Lutheran Church of America Records, 1875–1940,” Ancestry Library Edition. Father, Carl Friedrich Lohr, died in Beaver Dam in 1882 and was also recorded in the Evangelical Lutheran Church Records, suggesting this was the family’s primary denomination. ↵

- Marriage record, Anton M. Lohr and Johanna Caspary, November 25, 1884, St. Peter Church, Beaver Dam, Ancestry Library Edition. See also the wedding announcement: “West Bend,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 23, 1884, 6. Regarding the Caspary family’s religion, see this entry about Johanna’s father “Adam Caspary, Sr.” https://findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Caspary&GSfn=Adam&GSbyrel=all&GSdyrel=all&GSst=51&GScntry=4&GSob=n&GRid=32644428&df=all& accessed February 16, 2017. ↵

- This is the second firm of this name. The first was founded by older brother Charles Lohr (or Carl Lohr, Jr.) and Jacob Weifenbach in 1880 or 1881 when Gottfried Lohr’s departure broke up the Charles Lohr & Company Marble Works. This first Lohr & Weifenbach dissolved in January 1882 (“Dissolution Notice,” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, January 17, 24, and 31, 1882, 6). Charles went on to multiple successful monument businesses and other partners, but Weifenbach’s attempt to go it alone failed within a year and he moved on to the hotel and saloon business. It is this same Jacob Weifenbach who helped form the second Lohr & Weifenbach in 1891, this time primarily as a financial backer. ↵