“The Time Has Now Gone by When Things of This Nature Are to Be Hidden from the Public”: Mediating Bodily and Archival Violence

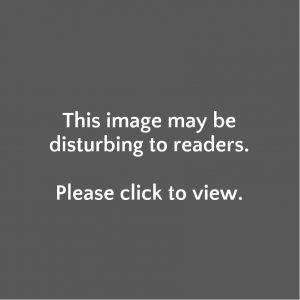

It was during a visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, DC, that I first encountered the abominable portrait of Martha Ann Banks’s injured body (fig. 1).1 On display in the museum galleries, the image represents a young Black woman seated on a chair with her dress stripped to her waist. With her back toward the viewer, the woman rests her weight precariously on the right edge of the seat while her left hand extends outward, across the chair, for balance. Her face carefully obscured, she turns to display the raised scars that cover her back, the back of her arms, and the back of her head. Although divorced from its original context, the image appears to be an enlarged photographic reproduction of a wood engraving. Its origins in the relief printing process are recognizable in the network of lines and crosshatching that define the woman’s form.

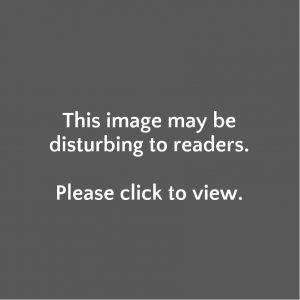

At the NMAAHC, the image is featured in the galleries as part of a large collage (fig. 2) that illustrates the lived experience of enslavement, wherein bondspeople built homes, developed crafts, and nurtured their families, and where, despite their varied experiences, the threat of violence was never far away. A wall label to the right of the image presents the unnamed subject simply as “Marks of Punishment Inflicted by Burning, Richmond, Virginia, 1866.” In the context of the museum’s display, the image of Banks’s scarred back is meant to serve not only as bodily evidence of the violence endured by enslaved persons but also as a way to underscore that American slavery was a fundamentally human experience, in counterbalance to the museum’s presentation of the legal and economic histories of enslavement on view in the preceding galleries.2 When I first saw the image of Martha Ann Banks, I was immediately struck by the formal similarities that it shares with the canonical image known as The Scourged Back. Taken by the photographers McPherson and Oliver in Baton Rouge in April of 1863, this widely reproduced photograph presents a formerly enslaved man known as both “Gordon” and “Peter” in a similar three-quarter pose.3 With his face registered in profile, Peter contorts his frame to reveal a scarred back that testifies to the brutality of his enslaved past. Originally produced as a carte de visite, Peter’s image was circulated, copied, collected, and displayed as part of abolitionist visual campaigns in the North and in Europe.4

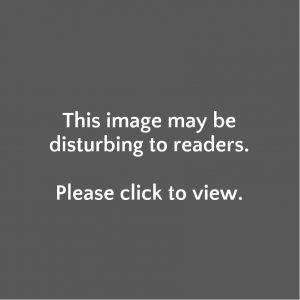

Peter’s image gained particular notoriety when it was published as a wood engraving in a special edition of Harper’s Weekly illustrated newspaper on July 4, 1863 (fig. 3). In Harper’s, Peter is renamed Gordon, and the image of his scarred back appears framed by two other illustrations that show his transformation from an escaped bondsman to a soldier, therefore demonstrating the redemptive power of military service and the potentialities of citizenship for Black Americans. This recuperative presentation was strategically used by Harper’s not only to strengthen public support for the war effort and emancipation but also to justify the enlistment of Black soldiers at a crucial moment during the war.5

As a historian of nineteenth-century photography and the illustrated press, I recognized the significant parallels between the image of Martha Ann Banks and that of Peter/Gordon, and I suspected that the image on display at the NMAAHC also derived from an illustrated newspaper. Wanting to know more about the image’s subject and the circumstances of its production and circulation, my research led me to ask difficult questions about what it means to work within an archive of racial subjugation—particularly as a white woman—and the political, ethical, and moral implications of attempting to recover the lives of the enslaved.6 What does it mean to more fully illuminate the experience of a subject in an image of atrocity? In finding out more information about Banks’s life, might I somehow redress the bodily and archival violence that rendered her an unnamed figure in a museum display? Moreover, how could I tell Banks’s story—or, a story of racialized violence—without committing further violence in my own act of narration? What steps could I take to extend care not only to Banks but also to potential audiences in presenting such images? These questions take on particular resonance in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement and attendant conversations around the circulation of images of Black suffering and traumatic death as a result of police violence.7

From my ongoing engagement with the portrait of Banks’s injured body, this investigation offers further insights into her life and the production of her image. I also explore how Banks’s image was circulated and framed through its use, particularly in the pages of Harper’s Weekly, where it was employed to activate the political agency of the periodical’s predominantly white readers. By examining the various forms of Banks’s image, this discussion reveals the layers of mediation that have delimited the historic narration of her abuse. The term “mediation” signifies not only the material translation of Banks’s image from one media to another, but also the ways in which her story has been transmitted and determined by historical actors.8 It is through unpacking these multiple layers of mediated obfuscation that I have been able to locate traces of Banks’s own voice. In addition, my research has allowed me to gain a fuller understanding of the ways in which Banks’s continued presence within the archive—and narratives of racialized violence more broadly—remains governed by racial power structures.

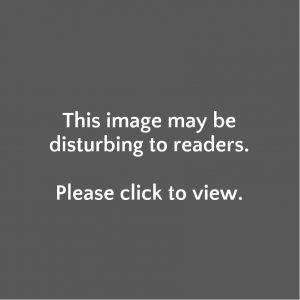

I soon learned that Banks’s image was originally published as a wood engraving in Harper’s Weekly on July 28, 1866 (fig. 4). Featured in the lower left register of the page, Banks’s partially naked and scarred body is triangulated in this publication by seemingly edifying examples of nineteenth-century white American womanhood. These include Mathew Brady’s portrait of the Union heroine Barbara Frietchie, and a sketch showing the latest trend in women’s bathing costumes. Likely selected for their similarity in female subject matter, the logic of the newspaper’s layout also constructs a narrative hierarchy, in which the suffering of Black women—such as Banks—serves as an anchor for the political agency and freedoms of white women in late nineteenth-century America.9 It is as if Banks, by force of association, is the passive beneficiary of Frietchie’s self-sacrificing resistance to the Confederacy, and Banks’s emancipation from enslavement is equivalent to the liberation of women from restrictive fashions. Captioned “Marks of Punishment Inflicted upon a Colored Servant in Richmond, Virginia,” Harper’s textual framing of Banks’s image further suggests that she serves a merely symbolic role by obscuring her identity and locating the subject of the image in the site of her injured body. This presentation contrasts with Harper’s earlier publication of the image of “Gordon,” who achieves a degree of masculine agency through the covering of his scars by his military uniform, an illustration of his embodied transformation from fugitive slave to soldier.10

An accompanying article, “A Cruel Punishment,” identifies the engraved image of Banks as made after a photograph sent to Harper’s by a “gentleman” in Richmond, Virginia, along with a letter that provides further context.11 According to the letter reprinted by Harper’s, the photograph shows the effects of “punishment by a hot iron on the back of a negro girl about 13 years of age, inflicted by a virago by the name of Mrs. A— living in King William County.”12 The letter, which renders both the victim and her female abuser nameless, reports that the girl had been “locked up in a private room, for some trivial offense, and kept in there over a week, during which time the burning was inflicted upon her.” The effects of this abuse are painfully rendered by the wood engraving process, as the engraver would have had to carve into the woodblock in order for the scars to be registered as white highlights against her dark skin. The article goes on to report that the girl’s abuser had been arrested and that the case was now under investigation by the Freedmen’s Bureau. As the author points out, many of Richmond’s white citizens denounced the bureau’s involvement and regarded the accused as a “martyred and chivalrous Southern lady” and not “the fiend that she was.”13

Declaring that “the time has now gone by when things of this nature are to be hidden from the public,” the article concludes by emphasizing that, “If the evidence were all published it would present one of the most cruel and heartless episodes of history that have disgraced civilization.”14 However, despite the import that is given to the story of this woman’s abuse, the evidence presented does not include Banks’s own testimony. Instead, her ordeal is told entirely through another witness, a characteristic feature of sentimental literature of that time. In sentimental narration, descriptions of Black female suffering were frequently deployed to awaken the feeling of white Northern actors—particularly white Northern women—and to mobilize them into political action.15 Yet, as Saidiya Hartman has shown, the creation of sympathetic representations of enslavement often displaced the personhood of the enslaved individual in the process of empathetic identification. As Hartman writes, “The other’s pain is acknowledged to the degree that it can be imagined, yet by virtue of this substitution the object of identification threatens to disappear.”16 In the context of Harper’s reporting, Banks is treated as a cipher, her injured body employed as evidence of Southern cruelty and as a call to arms for Harper’s readers during the battle over Reconstruction.

Banks’s image appeared in Harper’s at the height of debates over Reconstruction and the congressional elections that were set to take place in the fall of 1866. The Democratic Party, led by President Andrew Johnson, clashed with Radical Republicans over the terms by which the former Confederate states would be allowed to reenter the Union. The central issues in this debate were African American civil rights, and particularly whether voting rights would be granted to Black men.17 Favoring a policy of quick restoration for the seceded states, Johnson objected to imposing Black suffrage as a condition of readmission. Meanwhile, as a Republican newspaper, Harper’s endorsed Radical Reconstruction policies that would have punished the South and granted citizenship and voting rights to African Americans.18 Under the leadership of political editor George William Curtis, a supporter of full racial equality, Harper’s backed Radical Reconstruction by publishing articles that argued for voting rights for Black men, denounced prejudice against Black Americans, and condemned anti-Black violence in both the North and the South.19 The publication initially adopted a conciliatory tone regarding disagreements with President Johnson; however, by the end of the summer of 1866, Harper’s had begun to position the president’s policies as a threat to the nation. Taken in this context, the image of Banks’s injured body is presented less to illustrate the story of her abuse than to provide a counterargument to those who supported making concessions to the South in the lead-up to the 1866 elections.20

While the publication of her image and the accompanying article in Harper’s Weekly selectively recognize Banks’s humanity by denouncing the violence inflicted upon her, the newspaper ultimately denies her full humanity by obscuring her identity, neglecting to include her own voice, and marginalizing her experience by employing her narrative as a political tool. It was with an acknowledgment of the limitations—and inherent erasures—of Harper’s mediation of Banks’s narrative that I sought to find out more about her life.

The details in Harper’s Weekly allowed me to identify the young woman as sixteen-year-old Martha Ann Banks (born in 1849/50) of Aylett, Virginia. Historical newspaper databases reveal that the story of Banks’s abuse and the trial of her former enslaver, Mrs. Ann Catherine Abrahams, was widely reported in 1866. At least fifty-seven (unillustrated) newspaper articles were published in reference to Banks’s case and/or the extraordinary cruelty of her abuser. Significantly, the story of Banks and Abrahams appeared in newspapers all across the country—from the Daily News and Herald in Savannah, Georgia, to the Winona Daily Republican in Winona, Minnesota—and in Canada and Australia.21 These articles, which variously spell her name as “Martha Ann,” “Martha Anne,” “Martha Anna,” and “Martha Annie,” describe not only the shocking details of her abuse, but also the incredible efforts of Banks’s mother, Lucy Richardson, to rescue her daughter after having fled the Abrahams household from similar abuse the year before. Several articles also reprint excerpts from the Freedmen’s Bureau investigation, including surgical reports and eyewitness testimony, while others note the circulation of the photograph that served as the basis for Harper’s illustration.22 On their part, many Southern newspapers denounced the circulation of the story and Harper’s publication of the image as anti-Southern propaganda, arguing that it was unfair to charge the whole region with the alleged crimes of one bad person.23

The extensive press coverage demonstrates that the publication of Banks’s image by Harper’s Weekly occurred after her story was already in wide circulation. Indeed, the narrative of Banks’s abuse was essentially old news by the time of Harper’s publication, with the earliest known articles describing the case appearing in the Daily Morning Chronicle and The Press on July 4, 1866, more than three weeks before Harper’s own story.24 This delay can be attributed, in part, to the labor required to translate photographs into wood engravings, which involved a network of correspondents, editors, sketch artists, engravers, and typesetters. However, the delay in publication may have also been intentional, as Harper’s likely relied on a certain amount of prior knowledge on the part of their readers—gathered from daily newspapers—either of the case against Banks’s abuser or the existence of the photograph itself.25 Despite this delay, Harper’s editors clearly believed that the disturbing visual evidence of Banks’s scarred body was still relevant to political discourse, and in publishing the image undoubtedly drew upon readers’ recollections of The Scourged Back. By publishing stories that were already in wide circulation, we also can see that Harper’s was not publishing news—as we understand it today—but was instead acting as a digest, aggregating stories and images from a larger intermedial culture of information and then choosing to publish those that were suitable to their editorial goals.

With the help of scholar Matthew Fox-Amato, I was able to locate a copy of the photographic source for Harper’s illustration in the Wendell Phillips papers at Harvard University (fig. 5). The carte de visite portrait had been sent to Phillips by his friend John Oliver, who was then working for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Richmond. In a letter to Phillips, Oliver presents the photograph as evidence of the barbarism of slavery and describes his personal encounter with Banks, noting that, when she was first brought to see him at the Freedmen’s Court, she was too weak to get something to eat.26 Oliver also writes that the case had been brought before a Judge Advocate, but that at the time of his writing to Phillips, he had lost sight of the case. However limited, these personal details of Oliver’s encounter with Banks are striking, as such “intimate history” is otherwise absent from the press coverage of her story and is not visible in her photograph.27

Importantly, the survival of Banks’s image as a carte de visite points to the photograph’s intended distribution and use as an informational tool. The invention of the carte de visite, a form of negative-positive paper photography adhered to cardstock that enabled multiple, inexpensive copies of small images to be produced from a single exposure, created objects that mimicked the portability and ubiquity of the calling card. These objects played an important role in the visual culture of the Civil War, as they helped spread information among networks, both personal and political. The unique materiality of the carte de visite, including its portability and the potential for text to be added to the card mount, made it an ideal form for the communication of ideas. Although the scale of the carte de visite implied a sort of possession of the subject, many formerly enslaved individuals used the medium as a tool of self-representation and self-actualization.28 However, despite the capacity for self-empowerment located within the carte de visite, both Oliver’s circulation of Banks’s photograph and its translation as a wood engraving by Harper’s Weekly only speak to her symbolic form, as evidence of the barbarism of enslavement. Both sources acknowledge the case that was brought against Mrs. Abrahams; however, they fail to fully articulate Banks’s life without enslavement—including the resilience of Banks’s mother, Lucy Richardson, who returned three times to rescue her daughter—or how, in the early days of Reconstruction, the family was able to finally seek justice against their abuser.29

The various iterations of Banks’s image—from the photograph to the wood engraving to the enlarged reproduction on display at the NMAAHC—demonstrate a tension within the archive, between the extreme visibility of her body and the absence, or erasure, of her subjecthood. As Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson describe in their essay “Perpetual Returns: New World Slavery and the Matter of the Visual,” this tension is not unusual, as history has cast enslaved individuals into a “perpetual state of visual fugitivity” since the visual traces of enslavement continue to be obfuscated by the archives of the oppressive classes.30 Each form of mediation, however well-intentioned, brings Banks both in and out of view, as the image of her scarred body is used as evidence of the horrors of enslavement and as a site for the activation of empathetic identification, political activism, and historic narration.31 In this vein, it is worth considering that the image that I first encountered on display at the NMAAHC is itself an extreme form of mediation: an enlarged photographic reproduction of a wood engraving based on a photographic source.

The presence of Banks’s image at the NMAAHC captures not only the complexity of how narratives of Black female suffering have been disseminated since the Civil War but also how these tensions of visuality and obfuscation persist in the archive and therefore provide both limits on and possibilities for our work on the past.32 The approach I have taken, which focuses on unpacking the layers of mediation that have determined an image’s circulation and shaped the discourse surrounding that image—particularly with regard to the translation of photographs into wood engravings for illustrated newspapers—has helped me speak to this tension within the archive as well as my own subject position. As a white female historian, I must acknowledge my own inescapable role as a mediating force, in addition to my own privilege and the historic complicity of white people, whether knowingly or unknowingly, in anti-Black racism and racialized violence. This history has brought up fraught questions as I have thought about how to best engage with Banks’s image and her fragmented presence within the archive, while being mindful of the potential to perpetuate further violence in my own attempts at historical recovery and historic narration.

In the introduction to the special issue of Social Text entitled “The Question of Recovery: Slavery, Freedom, and the Archive,” the coeditors argue that there remains a “present, political purpose” to the project of historical recovery when it comes to the lives of the enslaved. Acknowledging that “historical recovery may never adequately restore the ontological totality of African-descended people silenced within the archive” and that “accounting for slavery may not unsettle the deep power imbalances that continue to permeate our world,” they conclude that even an incomplete history of the lives of the enslaved (or, in Banks’s case, formerly enslaved) remains a worthy—and even urgent—pursuit, particularly given the continued onslaught against Black life.33 It is with these imperatives in mind, coupled with a personal sense of political urgency in the wake of the police killings of too many unarmed Black men and women in the United States and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, that I have continued researching Banks’s life despite, and yet because of, the impossibility of historical recovery. This work forms a crucial component of my dissertation, in which I examine the publication and framing of photographic images of atrocity and their translation into wood engravings in Harper’s Weekly during the Civil War. I hope to be able to learn more about Banks’s life in order to illuminate more fully the tension between Harper’s exploitation of her image and her own articulation of her freedom.

Most recently, I was able to conduct research in the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau at the National Archives in Washington, DC. The archives present certain challenges for scholars, as researchers no longer have access to the original documents and must instead work from microfilm. The convenience of the digitized microfilms is undermined by a lack of clarity as some materials have become illegible in the translation from one medium to another, and the copying of multiple ledgers onto a single roll makes it difficult to understand cross-referencing. Searching for Banks under “B” for “Banks” and “R” for “Richardson,” her mother’s name, it was not until I tried “L” for “Layton,” the name of the Judge Advocate who presided over the case, that I found what I was looking for. It was there, filed under this white man’s name, that I found the original eighty-eight-page report of the case, including Banks’s own testimony. I am as yet unresolved about how to incorporate Banks’s testimony, which is primarily an account of her abuse, into my work as an art historian, though I hope to find ways to pair close visual analysis of the various forms of her image with primary research that will allow for the exposure of the historic and continued system structures of racism that have determined her presence within the archive. I also hope to find ways to share my recovery of this historical trauma and its historic contextualization without re-invoking trauma for those who still suffer within these racial power structures. Moving forward, I will continue to unpack the layers of mediation that have delimited the historic narration of Martha Ann Banks’s life and use the persistence of these violent erasures as a point of departure, rather than as a barrier, for future inquiry.

Acknowledgments

An early version of this research was presented at the Black Portraiture(s) V conference entitled “Memory and the Archive. Past. Present. Future.,” which was held at New York University in October 2019. I would like to acknowledge and thank the staff and archivists who have assisted me with this ongoing project, including those at the American Antiquarian Society; Houghton Library at Harvard University; the Library Company of Philadelphia; the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC; and the New York Public Library. This research was assisted by funding from the Joan and Stanford Alexander Foundation, as well as a Jay and Deborah Last Fellowship at the American Antiquarian Society and a Luce/ACLS Dissertation Fellowship in American Art from the American Council of Learned Societies. I am grateful to Matthew Fox-Amato, Jason Hill, and Jennifer Van Horn for their continued mentorship and insightful feedback on this essay, as well as my colleagues Christine Bachman, Alba Campo Rosillo, Emily Casey, Tiarna Doherty, Christine Garnier, Sabena Kull, Laura Sevelis, Christina Michelon, Ramey Mize, and Jill Vaum Rothschild, who helped me shape this material. Finally, my gratitude is extended to Emily C. Burns and Katelyn D. Crawford for their thoughtful comments and valuable editorial support.

Cite this article: Anne Strachan Cross, “‘The Time Has Now Gone by When Things of This Nature Are to be Hidden from the Public’: Mediating Bodily and Archival Violence,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10528.

PDF: Cross, The Time Has Now Gone By

Notes

- Although the image’s subject is unnamed in the museum display, my research has allowed me to identify the young woman as Martha Ann Banks of Aylett, Virginia. I have purposefully chosen to include her name here and continue to use it throughout the article. ↵

- I would like to thank Mary Elliott, curator of American slavery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, for her insight into this display. ↵

- Although this figure is perhaps best known as Gordon, the name given him to by the illustrated newspaper Harper’s Weekly, in acknowledgment of recent scholarship on the history of the image I will hereafter refer to this individual as Peter. Regarding the naming of this figure, and the various forms of his image, see David Silkenat, “‘A Typical Negro’: Gordon, Peter, Vincent Colyer, and the Story behind Slavery’s Most Famous Photograph,” American Nineteenth Century History 15, no. 2 (2014): 169–86; and Bruce Laurie, “‘Chaotic Freedom’ in Civil War Louisiana: The Origins of an Iconic Image,” Massachusetts Review: Working Titles 2, no. 1 (November 2016), n.p. ↵

- Regarding the circulation of The Scourged Back and its use in abolitionist visual campaigns, as well as newspaper reactions to the image, see especially Matthew Fox-Amato, Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). ↵

- “A Typical Negro,” Harper’s Weekly 7, no. 340 (July 4, 1863): 429–30. ↵

- On the problem of historical recovery, see, among others, Saidiya V. Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14; Stephen Best, “On Failing to Make the Past Present,” Modern Language Quarterly 73, no. 3 (September 2012): 45–74; Laura Helton, Justin Leroy, Max A. Mishler, Samantha Seeley, and Shauna Sweeney, “The Question of Recovery,” Social Text 125 33, no. 4 (December 2015): 1–18. On the potential problems inherent in linking historical work to the political work of redress, see also Walter Johnson, “On Agency,” Journal of Social History 37, no. 1 (Autumn 2003): 113–24. ↵

- For discourse surrounding the circulation of images of Black suffering and death, especially as the result of police violence, see Elizabeth Alexander, “’Can You Be BLACK and Look at This?’: Reading the Rodney King Video,” Public Culture 7, no. 1 (1994): 77–94; Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016); and William C. Anderson, “Against Consuming Images of the Brutalized, Dead and Dying,” Hyperallergic, June 1, 2018, https://hyperallergic.com/445105/against-consuming-images-of-the-brutalized-dead-and-dying; Allissa V. Richardson, Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #Journalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); Melanye Price, “Please Stop Showing the Video of George Floyd’s Death,” New York Times, June 3, 2020; and Allissa V. Richardson, “The Problem with Police Shooting Videos,” Atlantic, August 30, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/08/the-problem-with-police-shooting-videos-jacob-blake/615880. ↵

- For the various uses and definitions of media and mediation,” see W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen, eds., Critical Terms for Media Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). ↵

- Regarding the links between a discourse of Civil Rights and the histories of enslavement and racial subjection, see Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997). ↵

- Alice Fahs, The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 169; Franny Nudelman, John Brown’s Body: Slavery, Violence, & The Culture of War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 151–52; and Megan Kate Nelson, Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 173–74. ↵

- “A Cruel Punishment,” Harper’s Weekly 10, no. 500 (July 28, 1866): 477. ↵

- “A Cruel Punishment.” Notably, the term virago could have been used by Harper’s sincerely or ironically, as it means both “a loud overbearing {and potentially violent} woman,” as well as “a woman of great stature, strength, and courage.” See Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. “virago,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virago. ↵

- “A Cruel Punishment.” ↵

- “A Cruel Punishment.” ↵

- Franny Nudelman, “Harriet Jacobs and the Sentimental Politics of Female Suffering,” ELH 59, no. 4 (Winter 1992): 939–64. ↵

- Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 19. ↵

- “The President and the Suffrage,” Harper’s Weekly 10, no. 488 (May 5, 1866): 274. ↵

- For scholarship on popular press images created during Reconstruction, see Joshua Brown, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); David Tatham, Winslow Homer and the Pictorial Press (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2003); and Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005). ↵

- This included condemning the massacres that took place in Memphis and New Orleans the summer of 1866, the same summer Banks’s image was published. See “The Memphis Riots,” Harper’s Weekly 10, no. 491 (May 26, 1866): 321–22; “The Late Riot at Memphis,” Harper’s Weekly 10, no. 492 (June 2, 1866): 339; “The Massacre in New Orleans,” Harper’s Weekly 10, no. 503 (August 18, 1866): 514; and “The Apology for the Late Massacre,” Harper’s Weekly 10, no. 504 (August 25, 1866): 531. ↵

- This position is reflected in additional articles that I have found in other Republican newspapers that frame the story of Martha Ann Banks and Ann Catherine Abrahams within debates over Reconstruction. See especially “The Tactics of Our Adversaries,” The Press (Philadelphia), July 25, 1866, 4. ↵

- “Monstrous,” Daily News and Herald (Savannah, GA), July 31, 1866; Untitled, Winona Daily Republican, July 26, 1866, 2; Untitled, Ottawa Daily Citizen, July 27, 1866, 2; and “Condition of the South —Atrocious Cruelties,” The Age (Melbourne, Australia), November 2, 1866, 7. ↵

- “Horrible Outrage in Virginia,” Cleveland Daily Leader, July 25, 1866, 2; “A Difference—Black and White,” Spirit of Jefferson (Charles Town, WV), July 31, 1866, 2; and “The Case of Mrs. Abrahams,” Richmond Dispatch, July 31, 1866, 1. ↵

- On Southern opposition to the circulation of this story and the publication of the image of Banks’s injured body, see “Forney and Underwood in Partnership,” Richmond Whig and Public Advertiser, July 24, 1866, 2; “The Case of Cruelty,” Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, July 27, 1866, 2; “Radical Tactics—Their Method,” Weekly Progress (Raleigh), July 28, 1866, 3; Also see “A Difference—Black and White”; “Monstrous”; and “The Case of Mrs. Abrahams.” ↵

- Importantly, both the Daily Morning Chronicle of Washington, DC, and The Press of Philadelphia were published by John W. Forney. See “Shocking Barbarity,” Daily Morning Chronicle, July 4, 1866, 1; and “The Army—Shocking Brutality,” The Press, July 4, 1866, 2. ↵

- It is worth noting that the letter containing the photograph that was sent to Harper’s Weekly was dated July 3, 1866. Like other nineteenth-century illustrated newspapers, Harper’s likely advance-dated issues by one week, and the issue containing Banks’s image would have appeared on newsstands on July 21, more than two weeks after the writing of the letter. For the date of the letter, see “A Cruel Punishment,” 477; for the advance-dating of illustrated newspapers, see Brown, Beyond the Lines, 255. ↵

- John Oliver to Wendell Phillips, July 6, 1866, Wendell Phillips papers, 1555–1882 (inclusive), 1833–81 (bulk), MS Am 1953 (942), Houghton Library, Harvard University. Banks’s image is discussed in Fox-Amato’s recent publication, Exposing Slavery, 219–22. ↵

- I borrow the concept of intimate history from Saidiya Hartman, who uses the term to signify intimate interpersonal relationships, including kinship, child-rearing, domestic arrangements, and sexual relationships. I, however, deviate from that usage in that I intend intimate history to emphasize more quotidian corporeal encounters. See Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019). ↵

- For the role of carte de visite photographs in the history of Black self-representation, see, among others, Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds., Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013); and Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). ↵

- I am indebted to Dr. Khaliah Mangrum for illuminating this tension for me, between Harper’s use of Banks’s image as yet another example of slavery’s cruelty, and Lucy Richardson and Martha Ann Banks’s use of the image as part of their efforts to bring the law to bear on behalf of their family. See Khaliah Mangrum, “Picturing Slavery: Photography and the U.S. Slave Narrative, 1831–1920” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2014), 100, http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/108996/1/kmangrum_1.pdf. ↵

- Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson, “Perpetual Returns: New World Slavery and the Matter of the Visual,” Representations 113, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 3. ↵

- Copeland and Thompson, “Perpetual Returns,” 8. ↵

- Connections can be made between the historical conditions that delimited Martha Ann Banks’s fragmentary presence within the archive and the goals of the #SayHerName campaign of the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) and Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies (CISPS), which seeks to bring awareness to the often-invisible names and stories of Black women and girls who have been victimized by racist police violence; see https://aapf.org/sayhername. ↵

- Helton et. al, “Question of Recovery,” 7–11. ↵

About the Author(s): Anne Strachan Cross is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History at the University of Delaware