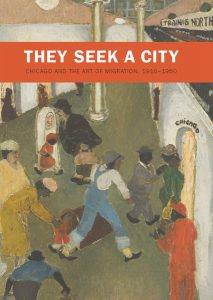

They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910–1950

Sarah Kelly Oehler

Yale University Press, 2013; 116 pp.; $35.00; ISBN 978-0300184532

Often cited as the Second City, Chicago and its artists—whether theatrical, visual, or literary—are regarded by many historians and the larger American populace as second rate in comparison to their New York counterparts. This viewpoint is felt in the relegation of Chicago-based modern artists as outsiders to the central narrative of American modernism in art historical surveys. But Sarah Kelly Oehler’s They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910–1950 –a companion publication to an exhibition organized at the Art Institute of Chicago of the same name –advocates for the complexity of work created by Chicago artists. Forgoing the traditional illustrated checklist and object entries often included in exhibition catalogues, Oehler’s book follows a tradition established by other art historians working within the city such as Amy Mooney, Daniel Schulman, David Sokol, offering a map of diverse, but socially-engaged artistic trends in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth century.

Often cited as the Second City, Chicago and its artists—whether theatrical, visual, or literary—are regarded by many historians and the larger American populace as second rate in comparison to their New York counterparts. This viewpoint is felt in the relegation of Chicago-based modern artists as outsiders to the central narrative of American modernism in art historical surveys. But Sarah Kelly Oehler’s They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of Migration, 1910–1950 –a companion publication to an exhibition organized at the Art Institute of Chicago of the same name –advocates for the complexity of work created by Chicago artists. Forgoing the traditional illustrated checklist and object entries often included in exhibition catalogues, Oehler’s book follows a tradition established by other art historians working within the city such as Amy Mooney, Daniel Schulman, David Sokol, offering a map of diverse, but socially-engaged artistic trends in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth century.

A number of exhibition catalogues that preceded They Seek a City made important cases for the significance of art produced in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth-century: for example, Chicago Modern: Pursuit of the New (Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 2004), Engaging with the Present: The Contribution of the American Jewish Artists Club to Modern Art in Chicago, 1928–2004 (Chicago: Spertus Museum, 2004), and Art in Chicago: Resisting Regionalism, and Transforming Modernism (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2004). The Koehnline Museum of Art in Des Plaines, Illinois, has produced a number of exhibitions about twentieth-century art in Chicago such as A Gift to Biro-Bidjan, Chicago, 1937: From Despair to New Hope (2002) and Convergence: Jewish and African American Artists in Depression-Era Chicago (2008) but they were accompanied by noteworthy brochures rather than full catalogues. All of these projects laid groundwork for They Seek a City, which adds to and further legitimizes these previous accounts.

In They Seek a City, Oehler argues that, despite the divergent styles and various subjects of artists working from 1910 to 1950, a form of unity existed among artists. She articulates that the book “is a necessarily selective examination of a particular moment in Chicago’s history, which features an artistic richness that points to the great impact of migrant and immigrant artists on the local art scene” (13). Oehler stresses how artists, both as migrants and immigrants, contributed to the local art scene’s multifaceted content alongside other Chicago-born and -based artists. Although the artists included in her study are often categorized as immigrant, migrant, African American, and/or Jewish, Oehler asserts that these identity signifiers influenced but did not limit their creative production.

The first chapter, “A Century of Progress: Immigration, Migration, and the American Scene,” examines how the influx of outsiders shaped cultural development in Chicago and across the nation. While many historians have cited the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in describing Chicago’s entry into the modern era, it is the 1933 World’s Fair that serves as a nexus for Oehler’s study. In a thoughtful description of the complexities of the fair, she writes, “In many ways, the fair was a microcosm of Chicago’s demographic, economic, and sociological divisions wrought by the forces of immigration and migration: it brought together people of all ages, backgrounds, and classes even as it revealed fractures within the city’s body politic” (21). Oehler reminds her readers that while the seminal event was a tremendous feat and included diverse elements, many cultural stereotypes were reinforced such as the area devoted to “Old Mexico” where white dancers were hired to perform. More broadly, Oehler explains that few employment opportunities existed at the fair for African American and Mexican residents of Chicago.

Beyond the background of the fair, in this opening chapter Oehler references the city’s numerous cultural offerings, sketching the setting from which abundant artistic production emerged in Chicago from 1910 to 1950. Oehler identifies spaces for community and social engagement in dancehalls, the literary renaissance of which Richard Wright was a prominent figure, and the Chicago Defender (the most popular black newspaper in the United States by World War I). Though these references are suggestive of forms of community in which larger community integration remained elusive, here lies an important point, one that is addressed by Oehler in this chapter and in subsequent ones: most migrants and immigrants were not welcome to participate in the communities created by the city’s white citizens.

The sections “Documenting the New Nation” and “Immigration, Modernism, and the American Scene,” located toward the end of chapter one, orient readers to artistic developments in the early twentieth century. Oehler contextualizes Chicago artists in terms of other developments in other parts of the country, most specifically in New York, and provides a way to compare and contrast the developments in Chicago. It can seem limiting to spend time reiterating events in New York in a book meant to highlight developments in Chicago, but this type of background information can legitimize the case for Chicago artists as peers, not secondary participants, in the narrative of American modernism.

By using the sociological study of assimilation as a framework, chapter two, “Making a Home: Immigrants and Migrants in the New City,” addresses how artists adjusted to the city while also reaffirming their own identities as both American citizens and artists. Oehler makes an important case for the role of institutions in shaping communities by situating many artists in relation to the Art Institute’s history, a recurring theme in the book given the publication’s use of the collection and the exhibition’s presentation at the museum. Through the lens of the storied Art Institute’s permanent collection, Oehler provides readers with a way to understand the developments of Chicago modernism in new ways that acknowledge several European-born artists who came to Chicago as immigrants, such as Emil Armin, Leon Garland, Todros Geller, and Morris Topchevsky, who studied at the School of the Art Institute. This is a rather interesting feat, as They Seek a City shines a spotlight on socially-engaged Chicago art of the first-half of the twentieth century through the Art Institute in a way that has not been done before.

Great art produced by a community does not emanate from one institution, but instead a rich cultural environment yields talented artists. This point is reiterated in Oehler’s second chapter as she includes a noteworthy discussion of a smaller yet hugely significant institution, the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC). Founded in 1941 with assistance from Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, the SSCAC offered classes and provided exhibition space for artists such as Charles White, Charles Sebree, and Margaret Burroughs. One of the most interesting facts provided is the first-year roster of exhibitions, which included We Too Look at America, an exhibition that featured (although not exclusively) the work of local black artists. Oehler writes, “The title is significant, for it indicates the sense among Chicago’s black artists that they were equally invested in depicting the national scene, drawing on their personal experiences as African Americans and, in many cases as migrants” (40). While the focus of the chapter is the simultaneous arrival of African American migrants from the South and immigrants from Europe and how these groups experienced a process of adjustment, Oehler hits a confident stride in her evaluation of African American art. She offers a riveting and thoughtful reading of Archibald Motley’s well-known painting, Nightlife, 1943, explaining that “as a fine art object, Nightlife depicted a self-contained black world of prosperity and amusement that would demonstrate to white audiences the achievements of African American migrants in Chicago” (46).

In the third chapter, “Fluid Boundaries: Chicago Meets Mexico,” Oehler continues her examination of the intertwined artistic relationships of migrant communities, focusing here on the artistic traditions of Chicago and Mexico. Oehler addresses the influx of Mexican migrants to Chicago, particularly citing the 1920s and 1930s as a major wave of immigration. She highlights points of connection between Chicago and leading Mexican artists such as the painter Adolfo Best Maugard, whose innovative design-based drawing method was adopted by ceramic artists at Hull-House, some of whom were Mexican immigrants, and the photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo, who taught at Hull-House for several months during 1936. Often overshadowed by his contemporaries from Mexico, Oehler’s acknowledgement of Maugard’s influence in Chicago makes a strong case for further study of his work and the translation of his teaching method in the U.S.

While Oehler cites exhibitions of Mexican art at the Renaissance Society and the Arts Club as vital to understanding the presence of Mexican modernism in Chicago during the first half of the twentieth century, her discussion of the history of Mexican art at the Art Institute of Chicago, linked with notable exhibitions such as an early presentation of the work of Mexican printmaker Leopoldo Méndez, make for a stimulating read. Again, this type of information effectively ties the larger context of They Seek a City to the collection and exhibition history of the AIC. In Oehler’s assessment, the influence of Mexican art and identity was fluid and multifaceted. It occurred through the presence of Mexican artists, art, and ideas in Chicago, the arrival of Mexican immigrants to Chicago, but also through the experiences of Chicago artists traveling to Mexico to glean artistic inspiration. While the book focuses on interrelated factors of migration and immigration to Chicago as catalysts for creative production, in the specific study of Mexican influences, Oehler acknowledges through a series of examples that the flow of movement was not linear.

In chapter four, “Forging a New Path: Migration and the Art of Social Change,” Oehler examines how artists in Chicago addressed shifting political and social struggles at international and local levels. The atrocities of World War II seeped into the consciousness of Chicago artists like Misch Kohn and Bernece Berkman who actively portrayed the human toll of war in the depictions of pain and suffering. Toward the end of the chapter, Eldzier Cortor and Marion Perkins are given ample treatment. Weaving biographical details with extraordinary works, Oehler does well to bring further attention to these dynamic artists. She writes on the former: “Out of the harsh reality of the kitchenette subject, Cortor created a dynamic, modern composition that rethought the idiom of social realism. By marrying beauty and squalor, Cortor heightened the impact of The Room No. VI, giving it an unforgettably visceral power” (84). Beyond explorations of daily life in the work of Cortor and socially impactful issues like oppression in the work of Perkins, both artists were also drawn to broader influences. Cortor’s elongated forms were inspired by African art and Perkins’ sculptures were informed by Christian themes, Oehler explains, emphasizing where these influences overlapped, such as in how Perkins “linked Christ’s anguish directly to the political and social experience of being black in the United States” (92).

In the epilogue, “The New Bauhaus: Design in Chicago,” Oehler moves away from the representational, overtly political work of the previous four chapters. Many previous studies have avoided discussion of the New Bauhaus and its relationship with other modern art trends like social realism in Chicago, typically viewing the New Bauhaus in isolation as opposed to in concert with the work produced by immigrants and migrants at spaces such as the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum and the South Side Community Arts Center. In They Seek a City, Oehler links them politically and through the larger framework of immigration. Oehler argues, “Moholy-Nagy’s works did not telegraph political messages in the way of the social realist artists then working in Chicago, and certainly his style was more abstract. But by confronting the specter of nuclear devastation, Moholy-Nagy revealed himself to be no less cognizant of social concern” (100). Like the socially-minded figurative painter Morris Topchevsky, who is given serious consideration in previous chapters, Moholy-Nagy arrived in Chicago as an immigrant, created political work, and left an indelible mark on the city’s art scene.

As numerous Chicago-based artists sought their artistic identities, they found the city a stimulating setting in which to create important work worthy of greater recognition. While they employed vastly different tactics, Oehler finds that “all believed that the struggles of their era warranted an evocative form of representational art that could draw attention to social conditions and create a better world” (95). In her book, Oehler builds on previous inquiries into art of the period and contributes extensively to our knowledge of and exposure to these noteworthy artists and the spaces and the institutions that nourished them. While various surprises occur throughout –in the form of emphasizing particular artists or uncovering little known or in some cases unknown works –it is the epilogue that draws the most revelatory conclusions and constitutes the publication’s most impactful contribution. By including the abstract, surreal photography created by György Kepes at the New Bauhaus, Oehler forces us to see the true breadth of work created by migrants and immigrants in Chicago from 1910 to 1950 and allows us to read both Kepes and Moholy-Nagy through the socially relevant work emphasized in previous chapters. Movement in the form of migration and immigration brought these artists within physical proximity to one another; their shared experiences yielded disparate yet socially invested artistic production. In its nuanced and illuminating exploration of this situation, Oehler’s book makes a compelling case for the significance of art produced by migrants and immigrants in the Second City and leaves readers to consider the placement of these artists within the larger narratives of American modern art.

Exhibition schedule: The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL. March 3, 2013−June 2, 2013

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1511

About the Author(s): Amy Galpin is Curator at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Rollins College