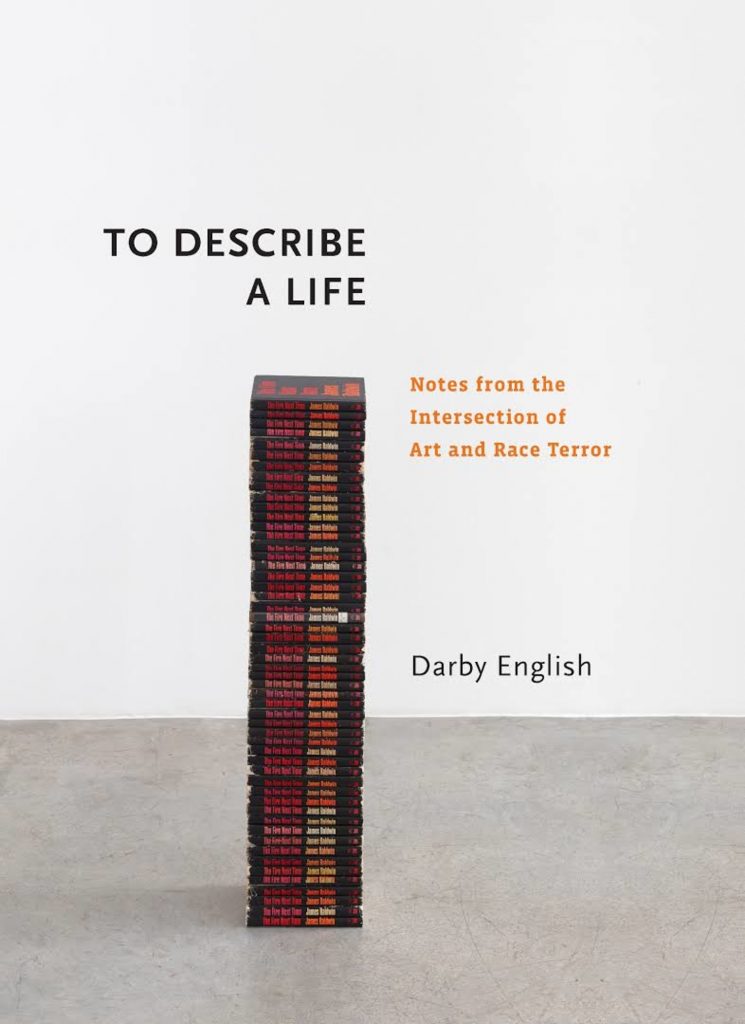

To Describe A Life: Notes from the Intersection of Art and Race Terror

by Darby English

New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, Harvard University, 2019. 148 pp.; 70 color illus. Hardcover: $35.00 (ISBN: 9780300230383)

New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, Harvard University, 2019. 148 pp.; 70 color illus. Hardcover: $35.00 (ISBN: 9780300230383)

In 2014, following the fatal police shooting of eighteen-year-old Michael Brown in broad daylight on a street in Ferguson, Missouri, Darby English recalled his overwhelming urge to respond to this murderous act from a “seemingly inapposite location,” namely the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where he worked as a part-time curator (7). Aided by colleagues, English’s response involved installing Benny Andrews’s collage painting No More Games (1970; Museum of Modern Art) in a high-traffic area of the museum in order “to recognize, outwardly, that a museum should offer no ‘escape’ from the predicaments that such events rouse” (7). Although “an expressively abundant statement about race relations,” the work also “honors the instability of its topics rather than elides it in the name of easy summary” (9). Deploying a singular work as part curatorial intervention and part catharsis served as a placeholder for To Describe A Life: Notes from the Intersection of Art and Race Terror. In an eloquent and oftentimes poignant introduction, English sets out the rationale for this approach. Notwithstanding the incalculable loss, pain, and anger produced by routinely catastrophic violent incursions into Black American daily life, he also notes how contemporary America remains beholden to a culture of division and indifference. From former President Obama’s racial inertia (under whose watch Ferguson erupted after Brown’s murder) to former President Trump’s amplification of white supremacy, embodied by murderous events in Charlottesville, Virginia, English contends that beyond anger and despair, certain artwork offers an alternative means by which to understand America’s perpetual crisis. Although the era of Black Lives Matter is certainly a catalyst for this book, it is by no means its main focus.

English declares his project as one of “critical reflection on culture” which challenges conventions in race-based thinking on art (xiii). Flipping convention on its head, he sets out to illustrate how art “complicates discussions of difference” (x). The introduction and subsequent three chapters in this richly illustrated volume each focus primarily on a contemporary work of art: a sculpture, a painting, an ongoing series of drawings, and a miniature architectural model, all produced between 1997 and 2016. Law enforcement, racialized nomenclature, and the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., are, broadly speaking, subjects that scaffold each of the three chapters. But, similar to Andrews’s work No More Games, each artist English addresses approaches the “urgent affair obliquely” (6).

This approach is evident in the introduction, where English considers Zoe Leonard’s Tipping Point (2016). Comprising a carefully arranged stack of fifty-three first-edition copies of James Baldwin’s nonfiction book, The Fire Next Time (1963), Tipping Point was Leonard’s response to “ongoing hypervisible destruction of black life by unchecked police power” (12). But for English, it beckons contingencies that far exceed his first impression that the work evokes “stacked bodies of shooting victims” or a “memorial” to the dead (15). On the one hand, Tipping Point summons reflection, reappraisal, or even a first encounter with Baldwin’s masterful exposé of America’s dependency on racism. On the other hand, Leonard’s sculpture performs physical and allegorical precariousness. A “hygroscopic” object prone to physical change, the sculpture is, as its title suggests, susceptible to collapse. English’s analysis has an ebb and flow; it undulates, and it is thoughtful, probing, and descriptively immersive.

Chapter one, “The Painter and the Police,” personifies English’s particular approach to “critical reflection” through an analysis of Kerry James Marshall’s painting Untitled (policeman) (2015; Museum of Modern Art). On this deadpan portrait of an imaginary Black male police officer, English argues that Marshall’s inspired response to the rhetoric of Black Lives Matter (24) obfuscates righteous indignation. It is “at first disappointing, then vexing, and then poignant.” (10). This summation strikes at the heart of the work’s provocation in throwing down a gauntlet. Marshall’s visually provocative and conflicted subject appeals to English’s formalist and cognitive sensibilities; he grapples with the compositional and painterly aspects of the painting in order “to attend to what barely can be detected” (41). Here descriptive analysis seems to function less as means to an end and more as an end in itself. English scours the painting’s mise-en-scène, its compressed picture plane. The near-abstract rendering of the police vehicle enhances the realness of the tightly cropped Black police officer who, “perched between being and image” (38), holds a palpably awkward pose. Referring to early preparatory sketches, English investigates Marshall’s processes and intention. Careful revisions brought to our attention are key to producing a subject that is more than an “assailant and victim in an indissoluble identification” (39). French philosopher Simone Weil’s “man of force” archetype, described in her 1939 essay “The Iliad,” is enlisted here to explicate Marshall’s amalgam of strength and weakness.1 Painter Sylvia Plimack Mangold’s floor and ruler paintings from the 1970s similarly inform Marshall’s “logic of pictorial representation” (33). Such historically grounded intertextual analysis, a feature throughout the book, deepens English’s capacious analysis and arguments. Such references also ratify how “discomposure” in America “requires interracial aesthetics” (21). Conversely, reference to contemporary art history and critical race theory are, by comparison, conspicuously absent.

Save for Marshall’s Untitled (policeman), English gravitates toward the nonfigurative. This offers respite from violent and dehumanizing imagery involving Black bodies, as well as media portrayals that present such “sacred losses in series” (2). Chapter two, “Differing, Drawn,” considers Pope.L.’s ongoing series Skin Set Drawings (1997– ), which comprise visually arresting, pithy but oxymoronic, hand-drawn statements rendered in watercolor, pencil, marker pen, and ballpoint pen. Here, English elicits insights about “irreal images, representations of people of who aren’t and never will be” (73). Drawings such as White People Are Pun (2001–3; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), Purple People Are I’ll Fuck You Whole Family and Cut They Shit Off (2011), and Green People Are On Rice (2004; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) flagrantly lampoon semantic conventions that interpolate the racialized subject. English offers a fascinating reading of Pope.L’s deployment of image and word, characterizing it as a conflict between representation and meaning.

English in this chapter is concerned with “physical outcomes,” how Pope.L “tinkers with the informational status of mark-making and its presentation” (47). The devil is really in the details. Take, for example, White People Are Pun, “one of the simplest” drawings (46). Here, English considers the minutiae of markings, the “pivoting strokes,” “overlapping touches,” and “staccato series of tonal highlights” (46). Although Pope.L’s drawings often lean into absurdity, they are also deadly serious in their critique of meaning in language. English succinctly describes this as “the project’s tendency to at once court and then frustrate (if not condemn) reading” (73). Therefore, we understand that Pope.L’s Skin Set Drawings do more than merely push back against the weirdness of racial language; they actively perform it. In keeping stride with the objects of his inquiry, English embraces and even excels in performing a “less-than-perfect legibility” (5). His punctilious essays are effusive but at times dense and perhaps tactically evasive. In this case, the medium is the message.

The final essay, “The King’s Two Bodies,” adopts a similar object-based analysis, albeit by a more circuitous route. Here, English first considers the fraught relationships between integrationist and separatist politics thrown into even sharper relief following the 1968 murder of Dr. King. English reads the post-King era through Ralph Ellison’s public attempts, in the early 1970s, to advocate for a continued belief in a shared “American language” (86). The catalyst for this preamble is Lorraine Motel, April 4, 1968 (1998), a miniaturized replica of the building outside of which King was assassinated. The work is one of five hundred miniatures produced by Constantin Boym and Laurene Leon Boym for their ghoulishly titled series Buildings of Disaster (1998–2008). Detailing its nooks, crannies, and perspectives, English drolly avers it is “not thinking deeply about much” (108). Save for the eponymous inscription, Lorraine Motel, April 4, 1968 is an inscrutable object. Unlike the other works in this volume, which lean on contemporary concerns, Lorraine Motel summons historical perspective; however, it is not maudlin. The hideous murder of King, the “furious optimist,” was one thing, but, English reminds us that this debit on humanity cost America dearly, not least “the specific complexity that the conversation on race lost” (97).

An exemplar of this faded past was the Freedom Summer Project of the early 1960s, which brought together a multiracial volunteer collective engaged and charged with registering Black Mississippian voters. For English, this hugely important event not only pushed back against Jim Crow, but today remains an example of “nonerotic social intimacy” that visualized a restructuring “between citizens and social space” (90–91). This analysis is compelling and affecting in its exhumation of a bygone era. English’s summation is that King’s demise heralded Black Power’s predominance, but that today’s cultural politics of difference, although compelling, perhaps too readily forgo a more nuanced summation of Black Power, which itself speaks to English’s view about “vernacular, organic epistemologies that crisis actually precipitates muddle those oppositions” (5).2 It could be argued that comparatively little is known about the Black Panther Party’s own stifled integrationist outlook, from its endorsement of feminism and gay rights to its brief transformative engagement with the Young Patriots, a working-class white supremacist organization.

English does not offer a formal conclusion to this study, remaining true to his misgivings about summation.3 Equally, it is a distinguishing feature of his formalist inquiry. The absence of a conclusion also inadvertently speaks to the interminable specter of police violence that continues to bedevil quotidian American life. To Describe A Life is a judiciously confected study. It is challenging but equally magnanimous, and it tenders an original and vitally important approach to thinking about art and race terror in contemporary America.

Cite this article: Richard Hylton, review of To Describe A Life: Notes from the Intersection of Art and Race Terror, by Darby English, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11820.

PDF: Hylton, review of To Describe a Life

Notes

- See Simone Weil: An Anthology, ed. Siân Miles (London : Virago, 1986) ↵

- See Colette Gaiter, “Chicago 1969: When Black Panthers Aligned with Confederate-Flag-Wielding, Working-Class Whites,” The Conversation, January 8, 2017, https://theconversation.com/chicago-1969-when-black-panthers-aligned-with-confederate-flag-wielding-working-class-whites-68961. ↵

- For example, in Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016). ↵

About the Author(s): Richard Hylton is Dietrich School Diversity Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Pittsburgh, 2019–2021