Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France

Emily C. Burns

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018; 248 pp.; 121 color illus.; 14 b/w illus. Hardcover $45.00 (ISBN: 9780806160030)

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018; 248 pp.; 121 color illus.; 14 b/w illus. Hardcover $45.00 (ISBN: 9780806160030)

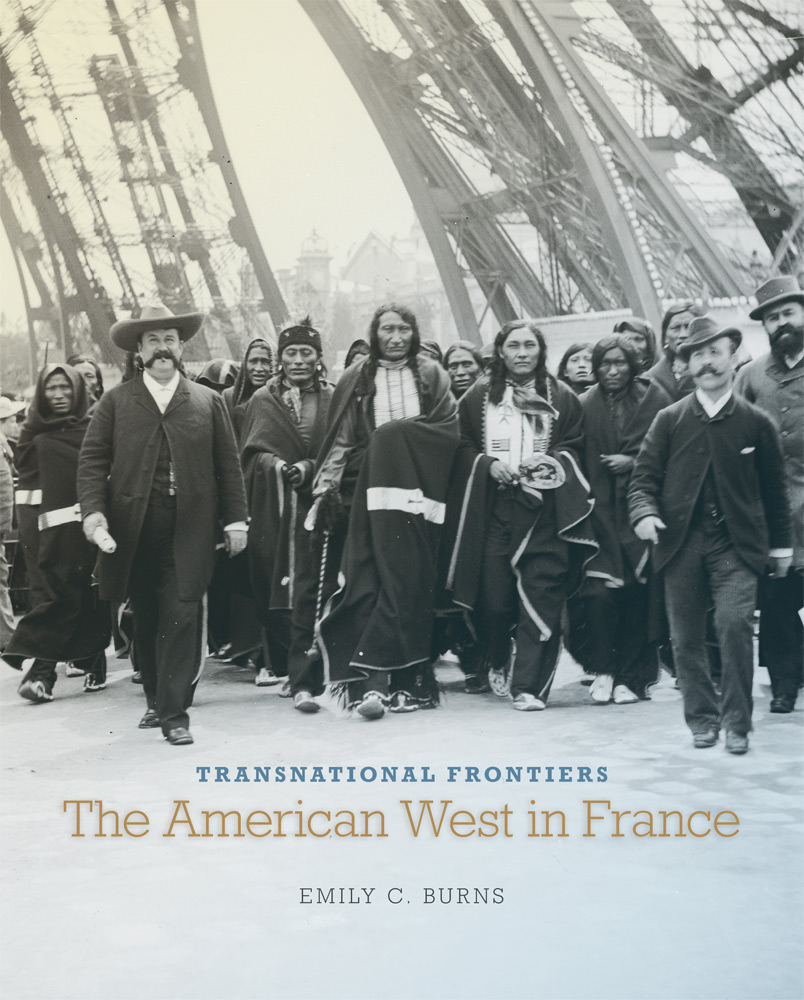

In Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France, author Emily C. Burns brings together an array of visual and material culture related to the American West in order to investigate Franco-American artistic exchange between 1865 and 1915. This scholarly book utilizes objects, including paintings, photographs, sculptures, and beaded buckskin coats, as primary documents in order to establish a dialogue with and build upon established postcolonial writings focused on indigenous agency and American identity.1 Burns crucially positions American Indians in France as active performers and participants on a transatlantic stage, asking us “to rethink the mobility and cosmopolitanism of indigenous peoples” (16). The powerful cover image of the book (an 1889 photograph by Giuseppe Primoli) reinforces this message in a presentation of Lakota men striding confidently toward the camera, framed by the base of the Eiffel Tower rather than the boundaries of the Wild West camp and other such spectacles.

A primary argument of Transnational Frontiers is that indigenous people carved out spaces for themselves in ways we may not immediately recognize today, and that artists aware of issues surrounding assimilation and survivance intentionally reproduced such spaces in their art. Fundamentally, Burns asks us to see American Indian men and women—especially the Lakota men given the title oskate wičháša (Lakota for “one who performs”)—as agents of their own self-construction within and outside of the arena and the photographic frame. In this context, indigenous arts and crafts become a powerful extension of American Indian agency and identity.

Burns emphasizes the universal expositions in Paris around the turn of the twentieth century as a means to situate indigenous agency within a dynamic conversation composed of other French and American bodies whose performances made manifest the American West as a transnational concept, defined as such because they “crosse[d] national borders and shift[ed] meaning in new contexts” (9). This is a work of crossed (rather than binary) history: one in which multidimensional interpretations coexist. Burns’s focus on microhistories of circulated objects and journeying peoples reveals how their points of overlap contributed to larger cultural issues. Each chapter therefore balances the micro and the macro, moving from close readings of specific objects to larger concerns about national identity and government policy. An example of this comes in the first chapter, in which Burns leverages a beautifully beaded buckskin jacket to question the meaning of “playing Indian” in France by French men and white and indigenous Americans. Burns first establishes how “playing Indian” was a double-edged sword for white American artists—it made them stand apart, but it also reinforced a pervasive idea that America lacked culture and refinement—and then utilizes photographic evidence to consider how American Indian performers Íŋyaŋ Matȟó and Sam Matȟó Išnála may have disrupted stereotypes even as they were seen to perform them. The buckskin jacket surfaces as a key component of French actor Joë Hamman’s “playing Indian.” This jacket, which he claimed to have received as a gift from Itȟúnkasan Glešká during a 1904 trip to Pine Ridge, South Dakota, played a central role in his cinematic mythmaking. Burns, however, reveals that it is unlikely Hamman ever went to Pine Ridge. Indeed, she presents strong evidence that he probably bought the jacket from Itȟúnkasan Glešká in France in 1911. By destabilizing Hamman’s myth, Burns returns attention to the jacket as an art object tied up in familial relationships, cosmopolitan networking, and indigenous survival. For some members of the Lakota nation, performing abroad in Wild West shows permitted behavior and activities—such as wearing traditional attire and speaking tribal languages —outlawed by the United States federal government and suppressed in boarding schools. Such performances allowed the Lakota men and women at the center of this book to carve out spaces for cultural renewal in Europe at a time of assimilation and reservation policy at home.

Throughout the book, Burns interweaves material and visual culture, archival resources, and fine art, although some chapters are driven more forcefully by the latter than others. For example, the second chapter turns to the work of French painter Rosa Bonheur and American sculptor Cyrus Dallin, who sketched together in Paris during the first performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West there in 1889. Burns suggests that Dallin’s critical views of United States government policy toward Native Americans may have pushed Bonheur’s paintings of Ógle Lúta and Íŋyaŋ Matȟó into the realm of “political intervention” (57). By painting Native American figures in unfenced landscapes (inspired by the relatively wild forests of Fontainebleau), Bonheur carved out a metaphorical space for indigenous survivance. This point is particularly relevant given the gross appropriation of Lakota lands by the US federal government in 1889. In his own work, Dallin, aware of such unjust government encroachment, emphasized the nobility and humanity of a people who were cruelly treated. Per Burns, the work of both artists sought “to question the relationships between identity and landscape, and to use visual metaphor to rebuild American Indian territories” (59).

Fine art also drives the third chapter, which focuses on the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris. While the exposition attempted to codify a display of America as an imperial authority, and of indigenous people as controlled, there was in fact “an uneven cultural pluralism in a diversity of styles, subjects, and stories. All of these identities were in flux, though all fell under the name ‘American’” (117). Burns moves between multidimensional readings of the works of American sculptor Solon Borglum, Rookwood pottery vases featuring Native American portraits, and indigenous arts and crafts to demonstrate this pluralism of style and identity. These exercises in multidimensional reading draw attention to the formal elements of specific objects while, as promised, embedding their reception and meaning within the context of Franco-American artistic and cultural exchange. After setting the stage with dichotomous readings of the American West on display at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris (dynamic/static, cinematic/ethnographic), Burns pivots to investigate the areas of hybridity between these poles. For example, the indigenous artwork on display—including academic portraits in pastel and traditional baskets and weaving—both signal assimilation and indigenous vitality. Furthermore, Native American artists such as Zitkala-Sa challenged stereotypes by playing classical music and writing about the challenges of her people, engaging with European and American culture in dynamic and multifaceted ways. In the fourth chapter, it is revealed that a hand-colored postcard of three Oglala performers was inscribed and sent by Jacob Ištá Ská (who was depicted on the postcard) to the French aristocrat Folco de Baroncelli. This fact asks for consideration of a Native American’s trip to a Belgian post office as a mundane errand conducted by myriad cosmopolitan tourists and not as an exotic occurrence. After decades of postcolonial scholarship these exercises in reenvisioning indigenous agency and identity should not come as a surprise, and yet they do. As Burns articulates, this is in part because of the way we have learned to see—or not see—historic indigenous people: usually in front of blank backdrops, suspended in time, “evacuated” of historical context (122). Burns’s book, like those of the scholars she builds upon, attests to the pervasive power of stereotype and the continued need to challenge its historical paradigms.

An interesting facet of this book concerns how and what the American West signified to French audiences at the turn of the century. Why, for example, were some Frenchmen, such as de Baroncelli and Hamman, such avid collectors of Native American visual and material culture, to the degree that they wished to construct their own Native American identities? In the first chapter, Burns uses these men as case studies to delve more deeply into French concerns about regional identity in the context of urban modernity and government control. The fourth chapter presents a fascinating exchange of material culture and friendship between Jacob Ištá Ská, an Oglala performer with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and the French aristocrat de Baroncelli. At stake here is the self-fashioning of identity through photography and personal letters of both men, and the extent to which each could, or would, acknowledge the nuances of the other’s constructed identity. In this analysis of a rich archive of letters, photographs, and de Baroncelli’s unpublished books, Burns reveals the arc of both Ištá Ská’s life (from boarding school student to international performer to Pine Ridge clerk) and de Baroncelli’s attempt to harness the power of Western imagery to champion his native region, the Camargue in southern France. Even Bonheur’s paintings of Native American men situated in the forest of Fontainebleau, discussed in the second chapter, must be understood as a comment on that forest as a liminal space between wilderness and modernity, and thus tied to regional French identity politics.

A consideration of the American West abroad would not be complete without its mythologized hero: the cowboy. Just as Burns considers in the first chapter the multifaceted interpretations and ramifications of “playing Indian” in France, in the fifth and final chapter, she considers the myriad possibilities for “playing cowboy.” For some French viewers, cowboys were a dangerous sign of American cultural incursion; to others, they symbolized a virile masculinity placed in opposition to urban decadence and effeminacy. Burns considers a variety of readings of these figures, reinforcing her point that the American frontier is a flexible metaphor with different, though often related, ramifications at home and abroad. The American West is not a distinct region, although it is often treated as such in art history. Its myth, concept, and imagined boundaries are constructed and reconstructed through diverse historic, cultural, political, and artistic contexts. By presenting close readings of where such elements overlap, Transnational Frontiers challenges us to consider the myriad possibilities of the West in the world, and the world in the West.

Cite this article: Jennifer R. Hennemann, review of Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France, by Emily C. Burns, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1689.

PDF: Henneman, review of Transnational Frontiers

Notes

- These include, among others, Philip Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998) and Indians in Unexpected Places (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 2004); Kate Flint, The Transatlantic Indian, 1776–1930 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009); Steve Friesen with François Chladiuk, Lakota Performers in Europe: Their Culture and the Artifacts They Left Behind (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017); Jace Weaver, The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000–1927 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); and Maximilien C. Forte, Indigenous Cosmopolitans: Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in the Twenty-First Century (Bern: Peter Lang, 2010). In keeping with the form utilized in Transnational Frontiers, “indigenous” is here used without capitalization. ↵

About the Author(s): Jennifer R. Henneman is Associate Curator at the Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum