Wandering Whalemen and Their Art: A Collection of Scrimshaw Masterpieces

PDF: Harrison, review of Wandering Whalemen

Wandering Whalemen and Their Art: A Collection of Scrimshaw Masterpieces

by Alan Granby

Foreword by Stuart M. Frank

Hyannis Port, MA: Alan Granby, 2021. 354 pp.; 661 illus. Hardcover: $85.00. (ISBN: 9780578859200)

There is a great deal of scrimshaw in the world: whaling scenes engraved on sperm-whale teeth; ditty boxes made of steam-bent baleen; corset busks fashioned from the jawbones of whales; jewelry and sewing boxes with inlaid whale ivory; pie crimpers, baskets, swifts, and innumerable other household items crafted from cetacean ivory and bone. Hundreds of pieces of scrimshaw feature in the sales of New England auctioneers every year, and thousands of pieces reside in the permanent collections of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, Mystic Seaport Museum, the Nantucket Historical Association, and other institutions. Many more examples are held in private hands, treasured by members of a collecting community so avid and competitive that prices for scrimshaw on the market have grown astronomically over the last quarter century.

Alan Granby is one of the principal dealers and collectors of scrimshaw in the United States. In 2019, the Cahoon Museum of American Art in Cotuit, Massachusetts, invited him to curate an exhibition of outstanding examples, drawing from his experience with the art form and his knowledge of both private and institutional collections. The result was the exhibit Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art, which ran at the Cahoon Museum from June 29 to October 30, 2022, and the accompanying publication, Wandering Whalemen and Their Art: A Collection of Scrimshaw Masterpieces, at once a catalogue for the show and an homage to the scrimshanders of the nineteenth century.1

The book is beautiful and large—measuring 12 1/4 by 13 1/2 inches and weighing over eight pounds. It is particularly impressive for its full-color photography, which reproduces, often at actual size, the more than three hundred objects that seven museums and nineteen private collections lent to the exhibition. Granby selected these examples for the quality of their workmanship and their representativeness, covering both the pictorial and utilitarian aspects of scrimshaw. To show the pieces off to best advantage, Granby worked closely with photographers and the book’s graphic designer to control the quality of the photography and printing. “Only a limited group of scrimshaw books exist,” he explains, “and I have always been acutely aware that the scrimshaw they feature is never true to the actual items in size, color or impact. With this volume, I decided that every effort would be made to show each item of scrimshaw as accurately as possible” (v). The book’s text is short and comprises a foreword by the historian Stuart Frank; an introduction by Granby; brief historical, biographical, and descriptive notes at the start of each chapter; and informative captions.

The book is organized as an overview of scrimshaw types; the goal, as the title of chapter 1 declares, is to demonstrate “the amazing diversity of the art of scrimshaw.” There is a short chapter on the materials of the scrimshander, one on key early artists, and another highlighting works by later-identified artists. The balance of the first 180 pages then focuses on scrimshaw as a pictorial practice, with 150 pages devoted to examples of images engraved on sperm-whale teeth, then nearly 30 additional pages of images on panbone and baleen plaques and corset busks. The imagery spans whaling scenes, patriotic emblems, naval subjects, fashion plates, and portraits. The book proceeds methodically in its concluding 150 pages to survey utilitarian scrimshaw: baskets, boxes, tools, household items, pie crimpers, swifts, and, finally, walking sticks, all made from the by-products of the whale hunt.

Frank’s historical foreword succinctly states the what and why of this maritime art form. In his definition, scrimshaw is

the indigenous occupational shipboard pastime of whalemen in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Age of Sail, using the hard byproducts of whaling—sperm whale ivory, walrus ivory, skeletal bone, and baleen, often in combination with other “found” materials—to produce practical, utilitarian, decorative, and ornamental objects for themselves and as gifts for folks back home. Scrimshandering was also occasionally practiced by the wives and children of the whaling captains with whom they sometimes went to sea, and was sometimes taken up by seamen in naval service and, less often, in the merchant carrying trades (xiv).

Granby’s introduction takes a quick look at the economic motivations behind American whaling and deals in a summary way with some of the aspects of work and life aboard a whaler. He also briefly describes the techniques of scrimshaw engraving. There are many more complete and better nuanced sources for whaling history and shipboard life, but as a setup for looking at whalers’ art, Granby’s notes are sufficient. The text is footnoted, although some of the citations to websites are carelessly vague.

The book does not trouble itself with the devastating ecological consequences of global whaling, which sought to harvest oil for lubrication and illumination and baleen for manufacturing from the bodies of cetaceans. The authors might have benefited from explicitly acknowledging that human attitudes toward whales have undergone a profound transformation since the Age of Sail, a transformation that necessarily colors the way many modern viewers see whalers’ art. Frank makes a special point to say that the appreciation and study of scrimshaw today is not tantamount to an approval of whaling. “It is well and prudent,” he writes, “to continue to control commerce in elephant ivory, which trade directly threatens the survival of elephants in the wild. However, scrimshaw never posed any threat to whales or elephants, either today or in the past” (xvi). True enough—Europeans and Americas did not hunt whales for their teeth or bone, and scrimshanding was a personal pastime—but without whaling there would be no scrimshaw. And what are readers to make of the continued creation of scrimshaw by artists today, when only materials from marine mammals harvested prior to 1973 are legal to use in the United States, and the art form has become almost entirely commercially driven? These questions are outside the book’s scope, but the book would be richer if these relevant issues were addressed.

There exist a few early examples of scrimshaw from the last half of the eighteenth century, but the craft truly developed after the Napoleonic Wars, first during the early 1820s in the British South Seas whale fishery and then in the American whale fishery starting in the late 1820s. Whaling was a notoriously unpleasant business, constantly in need of labor, and ship owners, agents, and captains hired nearly anyone they could get. Consequently, whaling vessels were manned by internationally and racially diverse crews, and the ranks of scrimshaw artists mirrored this heterogeneity. Frank points out that scrimshaw, while often classed as a folk art, was an “occupational art practiced exclusively by firsthand witnesses to the whale hunt, and by other deepwater mariners who were accordingly knowledgeable and technically proficient seafaring insiders” (xv).

The whaling scenes and ship portraits commonly engraved on sperm whale teeth tended to be original creations of the sailor-artists’ own imaging. Landscapes, portraits, and naval battles, also commonly found on surviving teeth, were more often copied from commercial illustrations of the day, particularly from the 1840s on, as popular magazines circulated widely among whaling ships. As a creative outlet for sailors far from home, scrimshaw was almost entirely a noncommercial activity. As Granby notes, “In the main, scrimshaw was done for the scrimshander. To pass the time. To express creativity. To keep the memory of an experience. Or to remind the scrimshander of a loved one far away” (xxi).

The chapter introductions are a mixture of helpful explanation and fluff. The chapter on scrimshaw baskets comments poetically but irrelevantly on ancient Babylonian, African, and Roman basketmaking but says nothing about how whalebone baskets might have related to other American or European basket forms in the nineteenth century (178). The chapter on tools starts with Homo habilis 2.5 million years ago in order to conclude that tools “remind us what an inventive species we truly are” (216).

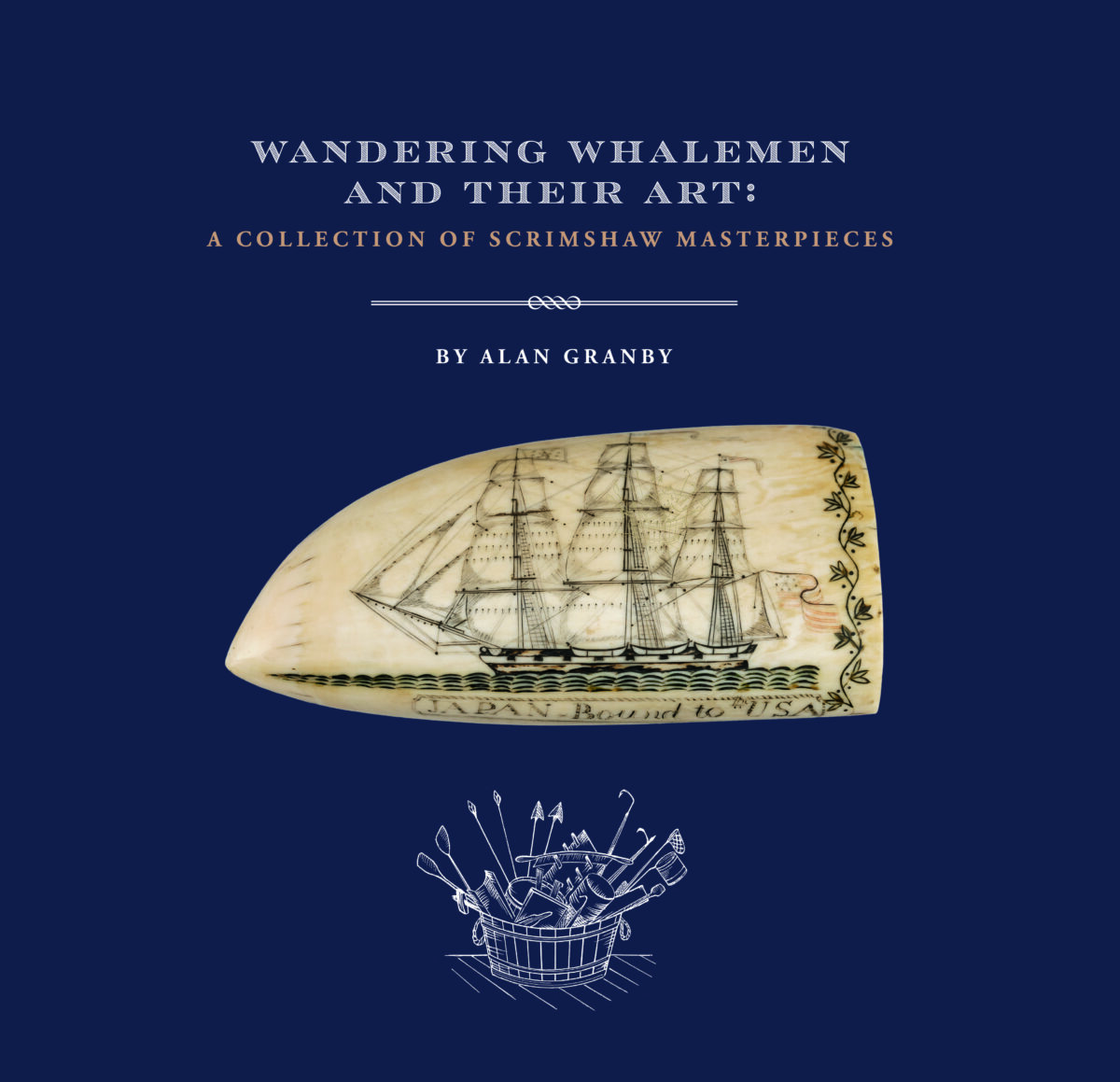

Nevertheless, the book truly is a compendium of masterpiece examples, selected by a practiced, appreciative, and enthusiastic eye. Chapter 3 features important works by key early scrimshanders. Edward Burdett of Nantucket (1805–1833) is the first American known to have engraved whale teeth. Four of the seventeen pieces attributed to him are illustrated in the book, including the important one labeled “Japan Bound to the USA” (ca. 1828–29), the earliest tooth yet attributed to Burdett and, by extension, perhaps the first American engraved whale tooth. In 2014, the collector Paul Vardeman discovered, through minute study, that many teeth attributed to Burdett were actually the work of a different hand, an as-yet unidentified British artist now called the Britannia Engraver. Five examples of this creator’s work appear in the book, each more astounding than the last. Frederick Myrick of Nantucket (1808–1862) was the first scrimshander to sign and date his work, and he is remembered for engraving about three dozen teeth aboard the ship Susan of Nantucket during 1828 and 1829. The book illustrates three of these “Susan’s Teeth” before surveying the work of four scrimshanders who sailed on the 1834–37 voyage of the ship Ceres of Wilmington, Delaware.

The early chapters on engraved teeth proceed from one remarkable example to another, while the later chapters are a feast of creative expression. A delicate pierced-work corset busk is crowned with a cross inside a heart—likely a gift fashioned for a loved one (171). A wood box is inlaid with abalone, whalebone, mother-of-pearl, and mahogany in a profusion of hearts, flowers, swags, compass roses, and patriotic shields (192). An oval box of steam-bent panbone is covered all over with engraved polychrome coastal scenes (207). A walrus tusk is carved into a boat tiller, with decoration simulating ropework (224). A tour de force wall pocket is made of carefully scroll-sawn panbone in geometric patterns (271). And the chapter on pie crimpers includes twenty-eight spectacular examples, including one with the word “GIFT” carved through the handle, with the letters of “FIDELITY” forming the carved spokes of the jagging wheel; Granby justifiably calls this piece “unique and amazing” (277–78).

Wandering Whalemen and Their Art is a visual celebration of spectacular examples by some of the most accomplished historic scrimshanders. One hopes it will encourage art historians, cultural historians, folklorists, and other scholars to look attentively at this art form and consider the creative lives of a substantial class of working individuals from the maritime past. There may be a lot of scrimshaw in the world, but, as this book amply demonstrates, the best examples produced by whalemen are well worth treasuring.

Cite this article: Michael R. Harrison, review of Wandering Whalemen and Their Art: A Collection of Scrimshaw Masterpieces, by Alan Granby, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17492.

Notes

- Artifacts from the Nantucket Historical Association were lent to Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art and are illustrated in Wandering Whalemen and Their Art, but neither the association nor the author of this review had a hand in developing the catalogue or exhibition. ↵

About the Author(s): Michael R. Harrison is Chief Curator and Obed Macy Research Chair at the Nantucket Historical Association.