Wayne Thiebaud: A Celebration, 1920–2021 and Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawing

PDF: O’Brien, review of Wayne Thiebaud

Wayne Thiebaud: A Celebration, 1920–2021

Curated by: Scott Shields

Exhibition schedule: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California; May 29–August 7, 2022

Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawing

Curated by: Scott Shields

Exhibition schedule: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, October 16, 2020–January 3, 2021; Toledo Museum of Art, OH, February 6–May 2, 2021; Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, TN, July 25–October 3, 2021; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX, October 28, 2021–January 16, 2022; Brandywine Conservancy & Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA, February 5–May 8, 2022

Exhibition catalogue: Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings, exh. cat. Portland, OR: Pomegranate, 2020. 212 pp.; 170 illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9781087501178)

This vibrant retrospective at Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum was a beautiful farewell tribute to Wayne Thiebaud (1920–2021) in the place he called home. The Sacramento-based artist passed away in December 2021. He has been famous worldwide since the early 1960s as the Pop artist who made movie-star bright paintings of the era’s middle-American delis and displays of diner food. Thiebaud’s “low” subjects were shockingly new, as were the bold graphic forms that he appropriated from popular and commercial art and combined with the high-art techniques of modern realist painting. Wayne Thiebaud: A Celebration, 1920–2021 presented selections from the artist’s long lifetime of constant creation, including the historically significant breakthrough paintings of the 1960s and much more. On display were 117 paintings, prints, and drawings—many never before exhibited—made between 1947 and 2019, from the Crocker Art Museum and the Thiebaud family and foundation collections.

This celebratory exhibition was a revised version of the earlier Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings, marking the artist’s hundredth birthday. It opened at the Crocker in October 2020 and remained on view for less than three weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the museum. Yet the exhibition toured as planned, traveling to four venues across the United States. It returned to the Crocker five months after the artist’s death and opened in late May as Wayne Thiebaud: A Celebration, 1920–2021, reimagined as a memorial in the region where many knew the artist as “Wayne,” an influential teacher and man of outstanding character.

Scott Shields, Thiebaud expert and inspired curator of both exhibitions, refocused A Celebration by organizing it more by subject, loosening the chronological order, adding color by installing vivid floor-to-ceiling photo murals of painting details, and evoking poignancy by including vitrines of Thiebaud’s art materials, pocket sketchbooks, and tools. Eighteen newly gifted figure studies and thumbnail sketches on paper provided further insight into his method. An exhibition featuring the artist’s daughter, Twinka Thiebaud and The Art of the Pose, was rescheduled to overlap with A Celebration and included portraits of Twinka that were completed by her father.

Although the show was the first overview of Thiebaud’s production to open since his death, Shields and the Crocker were not aiming for a critical revision. This was a celebratory tribute, fittingly presented at an institution that has been committed to the artist’s work for three-quarters of a century. The Crocker first presented Thiebaud’s art in 1945, organized his first one-person show in 1951, and hosted a solo show every decade after that.

On entering the spacious Celebrations gallery, the overall impression was one of energy and order: an installation mirroring the effect of the art. Many of the artworks in the show manifested Thiebaud’s interest in graphic power and theatricality, lending the exhibition an exceptional vitality. This sense of life was enhanced by the crowds of viewers and billboard-size photomurals of painting details representing the artist’s four traditional realist genres: still lifes, figures, cityscapes, and landscapes (fig. 1).

The exhibition began with four paintings made before 1961, the year Thiebaud found his mature style. Zither Player, a moody 1959 oil on canvas, was created when, as Thiebaud later recalled, he was struggling to find “that fundamental thing,” a personal voice and subjects that mattered to him. Although Zither Player was painted from life, using a model in the realist tradition, the gestural facture is Abstract Expressionist, signifying “art” in 1959. It is a successful hybrid of Abstract Expressionism and realism, like the contemporaneous work of Bay Area Figurative and second-generation New York School artists.

Nearby are four 1961 breakthrough paintings: Cold Cereal, Hamburger, Four Prone Figures, and Pies, Pies, Pies (fig. 2). The difference is dramatic. These early mature works are trademark Thiebaud: bright, colorful, realistic images that “tattle” on how middle Americans lived their daily lives in a well-lit world of convenience food and leisure time. With lavish care and skill, Thiebaud gave the barely noticed things of his world the charisma of movie stars, staging them carefully and visually tipping their performances into the viewer’s space. Food, primarily desserts in retail displays, is the subject of most of the still lifes in the exhibition, as in the artist’s oeuvre. Sheets of thumbnail drawings and prints in the show, like the twelve small still-life intaglio prints in the Delights series, offer insight into Thiebaud’s visual thought process.

Pies, Pies, Pies is an iconic painting of the kind that earned Thiebaud sudden fame in 1962 with his landmark show at the Allan Stone Gallery in New York (fig. 2). It displays many of his signature techniques: aggressive frontality; a tightly packed composition; insistent flatness; syncopation; a spectral palette; stage lighting; and colored shadows. The thin blue shadow line under each orange piecrust in Pies, Pies, Pies creates the halation effect that became a fixture of Thiebaud’s still lifes and figures, evident throughout Celebrations and most exquisitely rendered in the delicate 1992 Untitled (Row of Glasses).

In Pies, Pies, Pies, as in all the pie paintings, an impasto application of shiny oil paint mimics glossy fruit fillings and meringues. Painted cakes are similarly “iced,” and in Strawberry Cone (1969), a few masterful strokes evince softening raspberry-vanilla ice cream. Thiebaud derived his unique strategies from close study of works by masters of the Western mimetic tradition, especially the moderns, synthesizing their “tricks” with techniques from his extensive commercial-art background and his examination of artists like Walt Disney and George Herriman.

Seven figure paintings in oil were on view in Celebrations, as are pages of thumbnail sketches and eleven figure studies from the 1970s in ink, charcoal, and pencil on paper. First appearing in 1963, the figures are drawn from life and highly individuated, yet they are as objectified as the generic desserts in his still lifes. For Two Seated Figures (1965; fig. 3), a favorite with exhibition visitors, the artist’s wife and a friend posed anonymously. Life-size, the pair sit in straight wooden chairs against a flat off-white background with no illusory space behind the chairs, which puts them in the viewers’ room. Arms folded, they refuse eye contact with each other and the viewer. The sitters are performing parts, but the central role is the viewer’s. Since the two figures are in our space but ignore us, we can stare at them, invent a narrative, or study their shoes; we can pay them the kind of attention we give strangers in airports. Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book (1965–69), mounted nearby, is a portrait of the artist’s wife in which she appears as objectified as she is in Two Seated Figures. These works inspire existentialist interpretations.

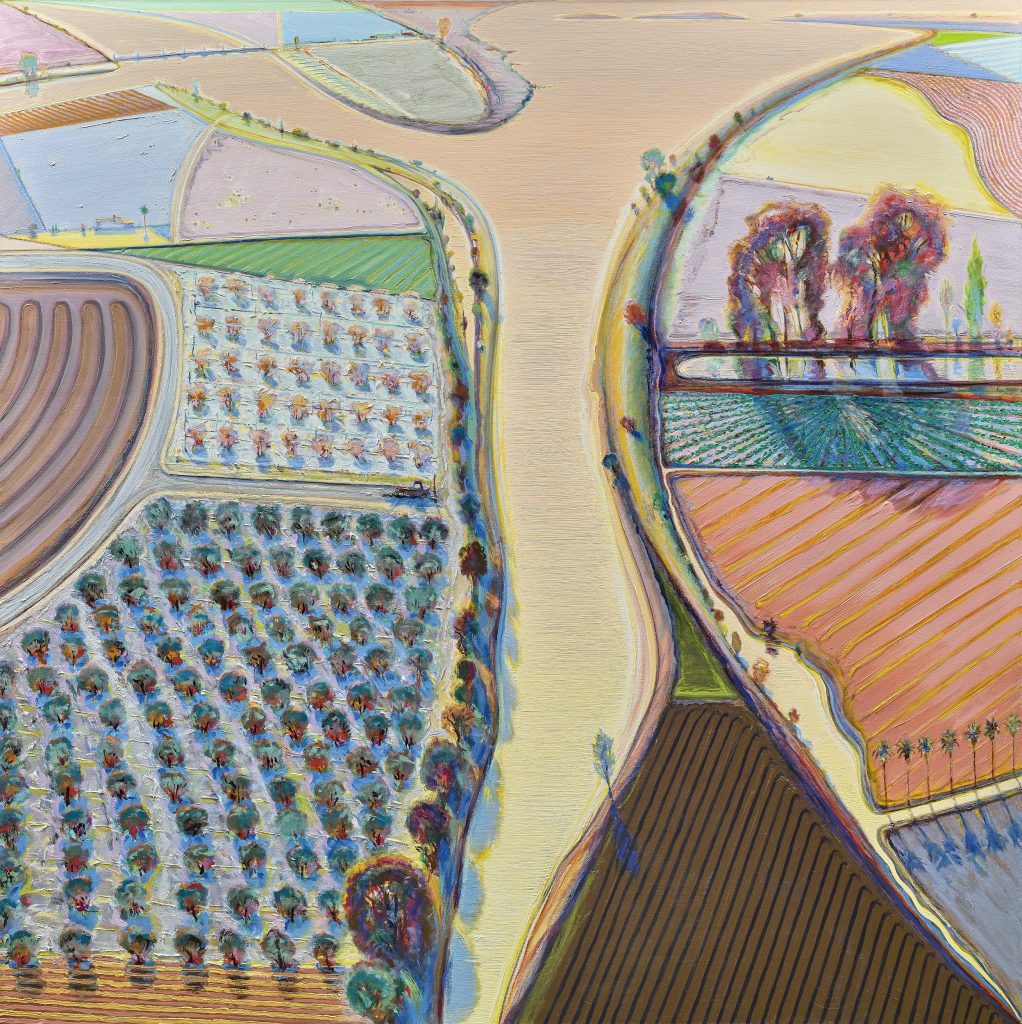

Celebrations included twelve landscapes, a theme Thiebaud began to explore for its abstract and sensual potential in 1966. A few landscapes in the show are traditional naturalistic impressions, such as Virginia Landscape (1981) and Auburn Hills (1984). However, the four fully realized paintings of the Sacramento River—Brown River (1998), River Lands (Study) (2005), River Intersection (2010), and Y River (1998; fig. 4)—give us Thiebaud’s unique vision, recalling Paul Cézanne’s views of Mont Sainte-Victoire in the way that they optically baffle and fascinate the eye, thus heightening the viewer’s sensation of being in the landscape. For Thiebaud, a painting potentially stimulates a physical “empathy” in the viewer. For me, his panoramas of the Sacramento River Valley capture the sights but also the sensations of road trips south on Interstate 5 from Sacramento: rolling hills—warm, dry, and golden in the California light—and distant mountains bordering both sides of the highway as it runs through the valley between endless parallel rows of vegetables, fruit and nut orchards, and irrigation ditches. Wide concrete canals of the California Aqueduct sometimes follow and intersect the highway. Y River (1998) recalls this experience for me vividly. Thiebaud gives us multiple viewpoints of the river valley, invented and drawn from memory and observation: a view high above milk-and-honey farmland looking toward a vanished horizon at the top, where a blue line suggests the earth’s curve. Low points of view for trees and other ground features make the experience irrational, a space of memory.

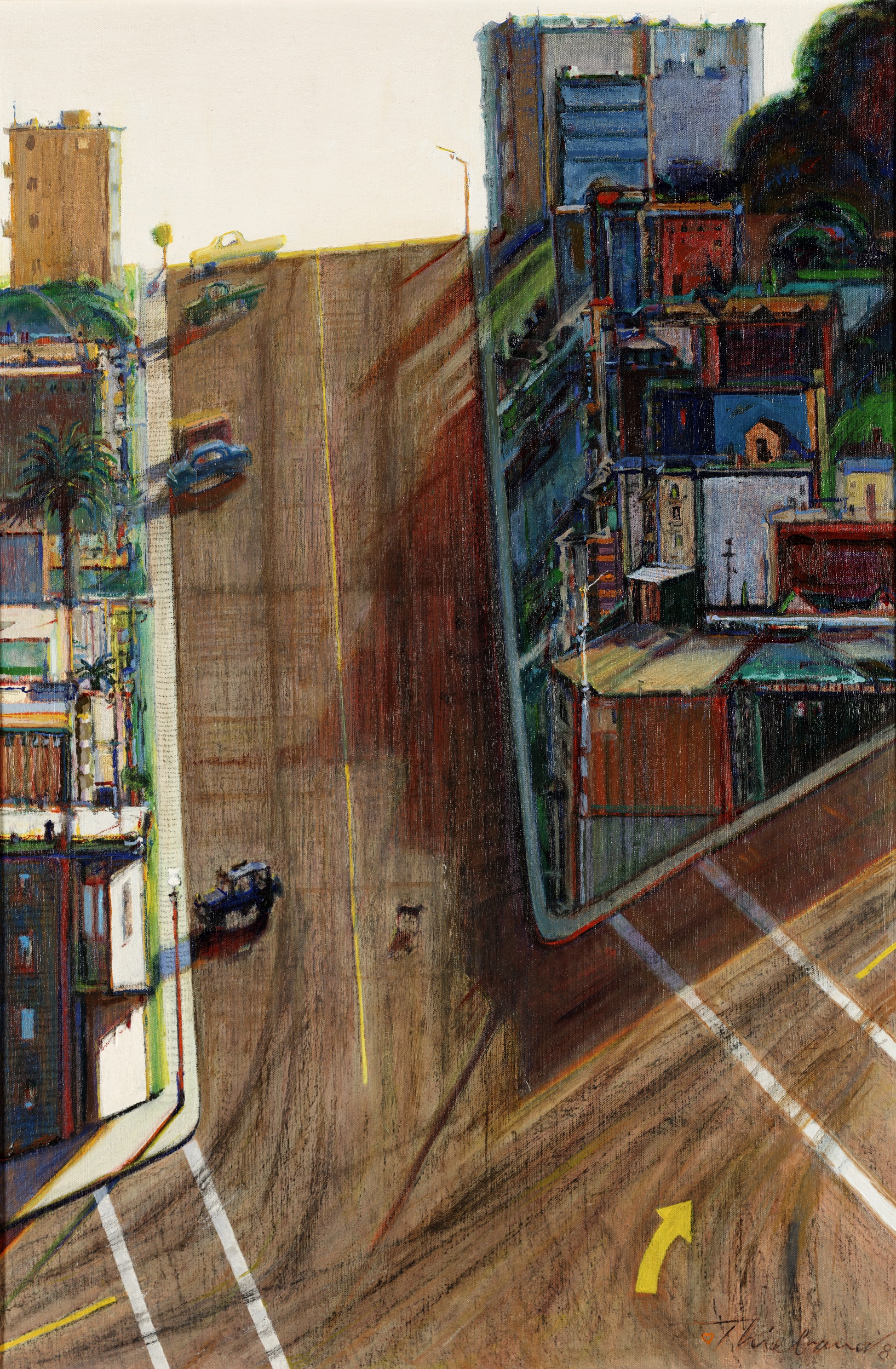

Thiebaud’s San Francisco cityscapes speak the same formal, abstract language as the Sacramento River Valley paintings, but they inspire wholly different sensations. Celebrations included ten San Francisco scenes comprising several drawings, a print, and five paintings: Street and Shadow (1982–83/96; fig. 5), Central City (1992), Steep Street (1993), Park Place (1995), and Sunset Street Study (2019). Like the river valley landscapes, the paintings are simultaneously abstract and narrative. The vertical plane of Street and Shadow is not a horizontal bird’s-eye view of quiet farmland, however. It is one of hilly San Francisco’s seemingly perpendicular streets. Thiebaud exaggerates the incline, evoking the roller-coaster sensation of driving in the city. Cars park impossibly, as if on a wall. Buildings flatten sideways into neat geometric patterns yet make long shadows on the street. There is that California light. Those who know San Francisco will recall the sights and sensations of navigating the city, its castle-by-the-sea quality, and the sense of sheer amazement that it was built like this.

Wayne Thiebaud: Celebrations, 1920–2021, was an inspired selection and installation of the artist’s lifework. It deemphasized the famous and historically significant Pop paintings of the 1960s, as the artist always wished, to give us a deep and expanded appreciation of his oeuvre and contributions as an artist. Thiebaud perpetuated the great Western realist tradition and enriched it with the brilliance of American commercial art and cartoons. His pictures record what life in his world looked and felt like, capturing the spirit and sensations of things and places with such fresh perception, invention, and graphic force that they will henceforth always be seen through his vision.

Except for eighteen new works on paper, all the artworks featured in Wayne Thiebaud: Celebrations, 1920–2021, were also in the earlier Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings exhibition and have full-page color plates in the Wayne Thiebaud 100 exhibition catalogue. Besides the many color illustrations of exhibited paintings, drawings, and prints, the catalogue includes historical photographs that help to situate Thiebaud’s work and life contextually. It contains four well-researched and considered essays by Thiebaud specialists that will make the catalogue one of the defining sources on this artist. Contributors include Scott Shields, associate director and chief curator at the Crocker Art Museum; Margaretta Markle Lovell, professor of American art history at the University of California, Berkeley; Hearne Pardee, professor of art studio at the University of California, Davis; and Julia Friedman, an independent art historian, critic, and curator. Mary Okin, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, currently completing a dissertation on Thiebaud’s contributions to the history of American art, produced a valuable, comprehensive chronology.

Cite this article: Elaine O’Brien, review of Wayne Thiebaud, A Celebration: 1920–2021 and Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings, Crocker Art Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15350.

About the Author(s): Elaine O’Brien is Professor of Modern & Contemporary Art History at California State University, Sacramento.