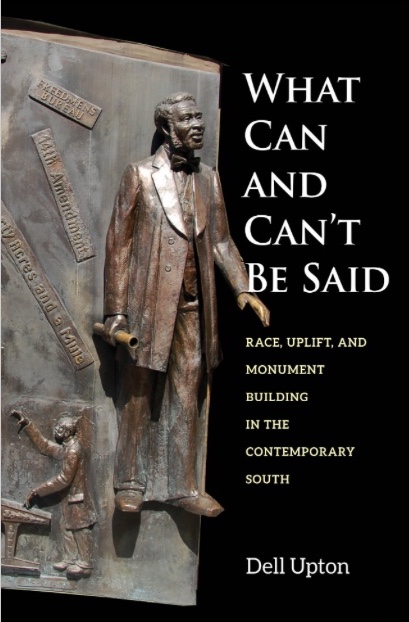

What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South

Dell Upton

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015; 280 pp., 59 b/w illus.; ISBN 9780300211757; Hardcover: $35.00

What Can and Can’t Be Said surveys overlapping periods of civil rights memorial construction. Upton begins with commemorative monuments of leaders, which grow from private gravestones and nineteenth-century traditions of glorifying public sculpture. He notes a shift around 1989 to “populist memorials” that emphasized local participants in the civil rights movement and finally moves to discuss more recent African American history monuments that consider the movement as part of the long freedom struggle. Upton situates these turns within histories of civil rights and of public sculpture in the United States. In the late 1980s, for example, Americans turned away from allegorical and representative figures, and civil rights activists called for greater recognition of the rank-and-file participants of the movement. Upton consistently and carefully connects aesthetics and politics, asking what can be articulated by “the Western monumental tradition” and “in contemporary American public discourse” (7).

Locating his narrative in a South defined as “the states of the former Confederacy,” Upton does not position the region as retrogressive, as behind in aesthetic terms or in the struggle for full equality (2). Instead he argues that it is Southerners who have “confronted, however evasively and contentiously, the implications of racial inequality for their society” in a way that others in the United States have not (7). For Upton, it is the rest of the country that is stuck in the “Martin Luther King Jr. monument phase,” one which honors a universalized version of King, a figure who has become comfortable to whites in part because his challenge to persistent inequities has become easy to ignore (7).

Moreover, Upton repeatedly gestures to the diversity among the states and cities of the South, all of which have different histories of civil rights organizing, racial violence, and monument making. Upton also continuously points out that race does not determine one’s views of a monument; there is no single, fixed “black” or “white” understanding of or argument for memorials. He is particularly attentive to disparities based on class, noting, for example, hostility on the part of lower-class and radical blacks who understand civil rights monuments to represent the history of others. This is particularly poignant in the case of Savannah resident James Kimble’s Black Holocaust Memorial (2002; Savannah), whose vernacular forms and “the poor black community in which it is based contradicts [the] rosy view” offered by the city’s official African American memorial championed by Dr. Abigail Jordan and designed by Dorothy Spradley (91). Analogous class-based differences also appear within white groups, including Neo-Confederacy groups and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. For Upton, civil rights memorials are equally complex. Not only do they accomplish benevolent work, but they are also part of the “rehabilitation” of the South’s reputation, the “social basis for a reinvigorated globalized regional economy,” and a way to mark the end of the civil rights era, foreclosing continued struggles for full equality (18–19).

The text highlights the process by which monuments are proposed, designed, approved, built, and understood as a site of “negotiation” and transformation, in contrast to studies of the physical form of a fixed object as “static memory” (24). Examining this process leads Upton to a remarkable range of sources: internet chat boards, intelligence files from the Southern Poverty Law Center, FAQ pages from the League of the South, blog posts on websites that have been discontinued, minutes of city meetings, and records of municipal planning processes. Upton also provides a litany of names and a fine-grained view of local events, which may confuse some readers about whose voice in this book is most “important.” However, that criticism is also an essential part of Upton’s contribution—an art history that takes into account the everyday interactions through which a monument is created, including the decentering of a stable patron/artist/viewer relationship in favor of coalitions formed by neighborhood activists, business leaders, concerned citizens, disenfranchised residents, and political officials.

These local-level negotiations occur as civil rights monuments celebrating racial equality enter an existing Southern monumental landscape devoted to white supremacy. In addressing this paradoxical situation, Upton’s first chapter explores the ideology of “dual heritage, which treats white and black Southerners as having traveled parallel, equally honorable paths” (15). Upton locates the origins of dual heritage in the aftermath of the Civil War, when whites demanded that blacks celebrate their emancipation and not Confederate (white) defeat. Dual heritage became a cornerstone of the so-called “New South” that edited enslaved African Americans from Southern history, reorienting the Civil War as a conflict about (white) “duty.” Upton demonstrates the ways that dual heritage ideology structures the physical context and politics of Southern monuments, wherein it is assumed that whites will enjoy veto power over new monuments proposed by blacks, but not vice versa. In revealing how dual heritage separates histories and heritages that are “inseparable,” Upton’s analysis is almost too clear and convincing (29). I initially wondered how anyone could hold such a bifurcated view of history, but days later began to consider dual heritage as a model for the frequent separation of the histories of African American art and (white) American art in our field. Upton’s writing stridently opposes the effects of dual heritage while showing the coercive power of the idea in the present.

The second chapter of What Can and Can’t Be Said focuses on uplift, exploring how the desire for “positive” histories confines civil rights memorials to envisioning “struggle . . . as endless, conflict-free progress” (196). Upton, who is the author of a survey text in American architectural history, locates the positive messages of civil rights monuments in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American ideals that formulated public space as “neutral and universal” (93).1 Since the early nineteenth century, memorial builders considered mourning and loss a private affair. Public feelings should look forward, “inspire rather than remind,” focus on “accomplishments rather than injuries” or conflict, and above all avoid divisiveness, the latter of which Upton powerfully unpacks as an injunction against offending white people (23). There are obvious gaps in the logic of uplift, which Upton addresses, but does not entirely explain away. For example, the continual assertion on the part of some whites that to erect or preserve a memorial should not be construed as a celebration of that history seems to contradict this model of public art; however, a consideration of the pressures for uplifting representations actually underscores the erroneousness of such claims to the neutrality of historical monuments.

Constrained by the ideology of dual heritage and demands for uplift, civil rights monuments speak predominantly in the visual and symbolic language of war memorials. Upton explores this mismatched pairing of a movement that offered a mostly nonviolent challenge to the state in the face of what was frequently state-sanctioned violence, arguing that civil rights memorials present war against enemies “who cannot be openly named” and “a triumph of good over nobody,” evoking the paradoxical situation of victims without victimizers (13, 20). While military terms are the national frame for celebrating struggle and sacrifice, the formal language of battles and heroes also distorts the representation of a movement comprised of masses of people who aimed to change their everyday lives. Triumphant civil rights monuments can therefore be used on the part of whites to suggest that the war has been won. As Upton points out, regarding this past as closed ostensibly allowed the 2013 Supreme Court to strike down key provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The question of aesthetic convention opens to a consideration of how our democracy might develop a visual language to integrate the diffuse, ongoing struggle for everyday civil rights into its national myth.

Alongside dual heritage and uplift, the book explores, in readable language, several complex models of history and its change, including collective memory, heritage, truthfulness, and the prevalent Southern belief that “the possibility of transformation through grace trumps history” (19). Crucially, Upton demonstrates that historians and their work can be mobilized on all sides of debates about monuments. Throughout Upton’s book we learn that historic preservation offices most often work to preserve the status quo, using a legal language to deflect political questions about whose history should be represented in public with “technicalities” that serve the interests of those in power (65).

A third chapter on monuments to Martin Luther King Jr. poses central art-historical questions of likeness and authorship. It could be productively assigned to any art history class dealing with the history of portraiture. Upton considers the ways that biography, character, and authenticity might be conveyed through resemblance. The chapter turns on protests against the commissioning of Lei Yixin, a Chinese sculptor, to create a monumental image of Martin Luther King Jr. for the National Mall. Upton explores the essentialist proposition in the “King Is Ours” campaign led by African American sculptor Ed Dwight, linking such calls for a black sculptor with a romantic intellectual tradition that holds works of art as “a revelation of the artist’s deepest personal attributes” (127). However, drawing on James Baldwin, Upton offers an argument against universalism and for the hiring of a black sculptor that was largely missing from the period debate and is laudable in its directness: “As long as African Americans are demonstrably hindered by persistent structural and historical conditions that prevent their being judged on individual merit, then ostensible color-blindness merely perpetuates existing inequalities” (125). Upton also clarifies the ways that monuments to King have removed him from his role as adversary to the state, including shifts in pose, changes to the monument structure, and clashes over the “authenticity” of quotations. For King to enter the Mall’s universalizing context, Upton argues, his confrontation must be with an opponent who cannot be named. This reduces his image to one of compromise and cliché.

Upton’s fourth chapter considers a park-turned–sculpture garden in Birmingham, Alabama, where he reads the “racial landscape,” offering a model of complexity that is both geographic and political. A secure African American political majority freed the mayor’s plan from certain challenges faced in other cities. Upton focuses on a sculpture, Dogs (James Drake, 1991), whose emotional intensity invokes a sense of victimization rather than uplift. Ultimately, he considers the monument as the outer limit of what can be said, as it communicates “a visceral experience of the white abuse of power as an ongoing, or potentially renewed, phenomenon” that might transmit the racial experience of being black in Birmingham (169).

Given the title of the 2015 book by Upton, it is perhaps unfair to look to it for an answer to the now-pressing question of what can be done with monuments to white supremacy throughout the world.2 However, What Can and Can’t Be Said does close with discussion of a few exemplary monuments that begin to overcome dual heritage and uplift. For a reader taught to look critically by the rest of Upton’s text, this attempt to find “successful” projects in the present seems an abrupt and less convincing shift in tone. Nonetheless, his book is full of examples of interventions that range from adding new labels to planting bushes to hide old labels, from a formerly central monument in New Orleans neglected in an “obscure corner” to one stolen in Selma and never recovered. A New Orleans newspaper strikingly suggests putting a monument “into a museum that would make clear its ‘fossil character’” (55). Upton’s book ultimately argues that the ideology of dual heritage along with narratives of uplift stand in the way of any change that is more than piecemeal. These beliefs represent the “remnant of white supremacy that still pollutes American politics [and] will eventually be scrapped, along with its monuments” (212). Here, as in so much of Upton’s book, his clear prose does not equivocate.

While I am much better informed about Southern monuments after reading What Can and Can’t Be Said, I still hold the same opinions about monuments in the South as I did before reading. Sitting with Upton’s book, however, has made me rethink a seemingly much smaller topic: my initial disappointment in the illustrations of monuments included in it. Most of the fifty-nine photographs were taken by the author and all are printed on cream, matte paper. The images are relatively low contrast, include power lines and other urban detritus, and are taken from angles that seem legibly uninteresting. Picking up the book, my first, barely conscious thought was that this was a history book and not an art history book. I now realize that my disciplinary attachment to seeing objects in person (or being made to feel that way through lavish color images) often blinds me to the full significance of the implicit conventions of art history. I now see these illustrations as a part of Upton’s method to put such monuments into their everyday context, to repeatedly remind us that they were made by and must be evaluated in the public sphere. These monuments are not (or not yet) cordoned off and presented as fossils in white cubes. Upton’s images resist glorification because there is little to glorify. What Can and Can’t Be Said provides a model of art history against uplift; public art does not solve or create racial inequality and tension, but it does provide a visible site for the ongoing negotiation of our often ugly, always interwoven pasts.

For a Bully Pulpit guest-edited by Upton and informed by this book, please click here.

Cite this article: Lauren Kroiz, review of What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South, by Dell Upton, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 1 (Spring 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1648.

PDF: Kroiz, review of What Can and Can’t Be Said

- Dell Upton, Architecture in the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998). ↵

- In 2017, Upton weighed in on this issue for the Society of Architectural Historians blog. http://www.sah.org/publications-and-research/sah-blog/sah-blog/2017/09/13/confederate-monuments-and-civic-values-in-the-wake-of-charlottesville ↵

About the Author(s): Lauren Kroiz is Associate Professor at the University of California, Berkeley.