Inside the Outsider’s Gaze

In 1998 I was invited to contribute an essay on Philippine basketry traditions for an exhibition at a university museum in the United States, coinciding with the centennial of the Philippine declaration of independence from Spain in 1898. Ironically, the year 1898 also marks the US conquest of the Philippines: Were the US celebrations commemorating Philippine independence from Spain or the ascent of US power overseas? Likely reflecting mainstream scholarly anxiety surrounding the topic of imperialism at the time, I was asked to delete a paragraph on violent US military interventions impacting local populations, which, at that time, I did. With the global turn in art history and the corresponding material turn in history illuminating the intertwined lives of objects, global histories and geopolitics, it is time for art historians to reconsider the agency of empire and the multidirectional flows of objects, materials, and ideas between imperium and colony, center and periphery. A new exhibition on the historic year 1898, currently planned for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, whose curatorial brief boldly cites the “bloody combat known as the Philippine-American War,” will be an important litmus test on the progress being made today in redressing US intellectual hegemony.1

The forthcoming exhibition aims to “explore the historic year of 1898 by comparatively addressing the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, and the Annexation of Hawai‘i.”2 The goal articulated by the exhibition curators—to examine the events of 1898 “through a comparative approach, including the perspectives of all of the countries involved”—brings up the question of who will attempt to illuminate the “perspectives of all the countries involved.”3 In trying to bridge the gap between the imperial gaze and the subaltern’s standpoint, is it possible for scholars at the center to get inside the outsider’s gaze? Early scholars often claimed authority to speak for the Other after research visits of a few weeks, months, or perhaps even a year or two. Is this legacy to be continued? Perhaps a collaboration between insider and outsider scholars is envisioned—a complicated enterprise. A recurring challenge in comparative studies and multicultural scholarly collaborations is the fundamental preoccupation with hard facts among most scholars in the peripheries versus the primacy of theory among their mainstream colleagues. Intellectual focus on retrieving historical details and accumulating data characterizes much of outsider scholarship. How is the opposition between the western preoccupation with the latest fashionable theory and the colonized scholar’s obsessive quest to retrieve and re-inscribe historical specificities in the context of the recurring theoretical question of “cultural identity” resolved?

In this brief essay, I revisit the US imperial legacy in the Philippines from an outsider’s gaze, one that is necessarily informed by the epistemic legacies of empire and borrowed colonial languages. I explore possible methodologies for decolonizing scholarship by sharing specific strategies in reconsidering and (re)interpreting Philippine and American art in the imperial diaspora. I cite two examples: a forthcoming volume on colonial and commercial engagements among Asia, the Americas, and Europe from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries and the work of American architects Daniel H. Burnham (1846–1912) and William E. Parsons (1872–1939) in the Philippines at the turn of the twentieth century. By posing questions requiring more complex answers than can be discussed here, I hope to encourage self-critique and paradigm shifts.

Aspiring toward a global art history done globally, a forthcoming volume entitled Transpacific Engagements: Trade, Translation, and Visual Culture in the Age of Empires, 1565–1898 that I am co-editing with Meha Priyadarshini was conceptualized, funded, and published in equal partnership among three institutions based on three continents: the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (Florence, Italy), and the Ayala Museum in Manila.4 Scholars from Asia, the Americas, and Europe provide a diversity of voices intended to help bring the reader closer to the complexities of the transcultural, transpacific experience during the Western world’s quest for economic control of the Asia-Pacific trade. For example, the impact of New England’s nineteenth-century trade with China and Manila is examined from opposite geographies: Caroline Frank’s essay from the vantage point of Providence, Rhode Island, and mine from the lens of Spanish-controlled Manila, Philippines.

In her essay “Federal United States Imperial Aesthetics: The Asia-Pacific as Classical Antiquity and Capital Future,” Frank poses an important question for art historians: Why have Asian-Pacific aesthetics been relegated to a side story in interpretations of federal-era arts and architecture rather than an integral part of this period’s neoclassicism? She explores the insertion of Asian-Pacific iconography in the imperial imaginary of domestic space, such as the neoclassical mansion of Rhode Island merchant and former US consul to China, Edward Carrington. Frank discusses in detail how the strategic installation of wallpaper panels portraying idyllic scenes of the Pacific, created by the French manufacturer Dufour, promoted the “colonial gaze” even as other wealthy New England merchants, like Carrington, commemorated commercial success through related imperial aesthetics.

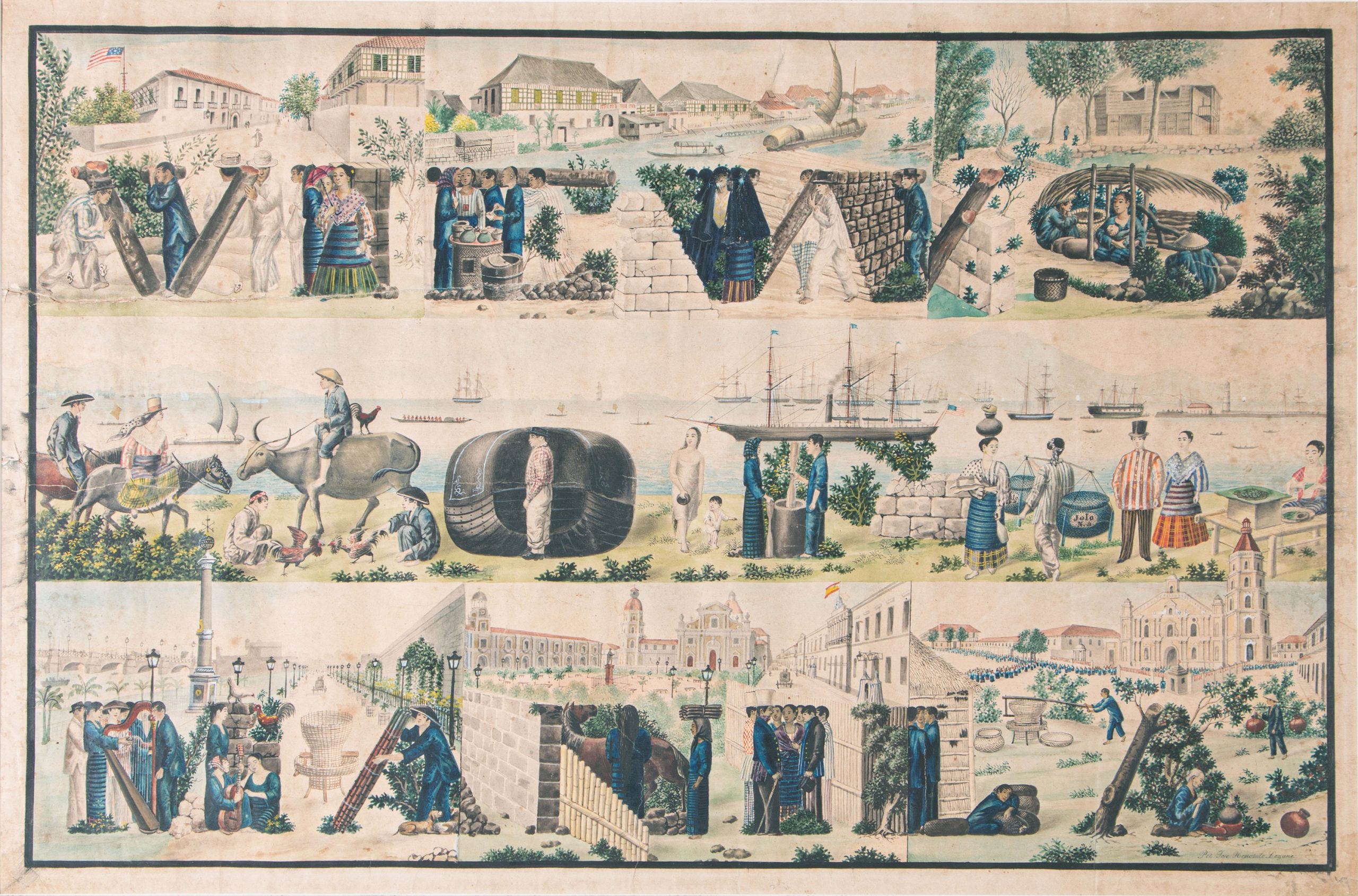

In counterpoint, my essay entitled “Inscribing Identities: Nineteenth-Century Export Watercolors and the Manila-Massachusetts Trade” focuses on US economic ascendancy and artistic patronage in Manila, oceans away from Carrington’s house in Rhode Island but linked by the same trade network. A type of export watercolors circulating during the period of early American trade in Manila, called letras y figuras (“letters and figures”), spells the patron’s name or other words and phrases using intertwined human figures. Already a popular artform among the Filipino elite and their Spanish colonizers, letras y figuras found a new market with the arrival of New England merchants. Local artists worked with Filipino, Spanish, and New England patrons, cleverly inserting visual clues alluding to the patron’s personal history and occupation (fig. 1). Examination of signed and unsigned letras y figuras and a related genre called tipos del país (“country types”), similar to Latin American costumbrista paintings, has made it possible to identify specific styles and retrieve the names of early Filipino artists. Moreover, surviving examples of both are valuable historical documents illuminating the identities and lives of New England merchants, Spaniards, and Filipinos engaged in intersecting commercial transactions in Manila. So here we have two essays on New England trade from opposite geographies and standpoints—one addressing the theory of imperial imaginary in the metropole and the other retrieving granular data (biographies and painting styles) in the colony—both attempting to recover and situate micronarratives within the metanarrative. As Dana Leibsohn notes in her afterword to the anthology, entitled “Pacific Matters, and Otherwise,” this inclusivity is not a frictionless enterprise, but it can invite new modes of thinking.

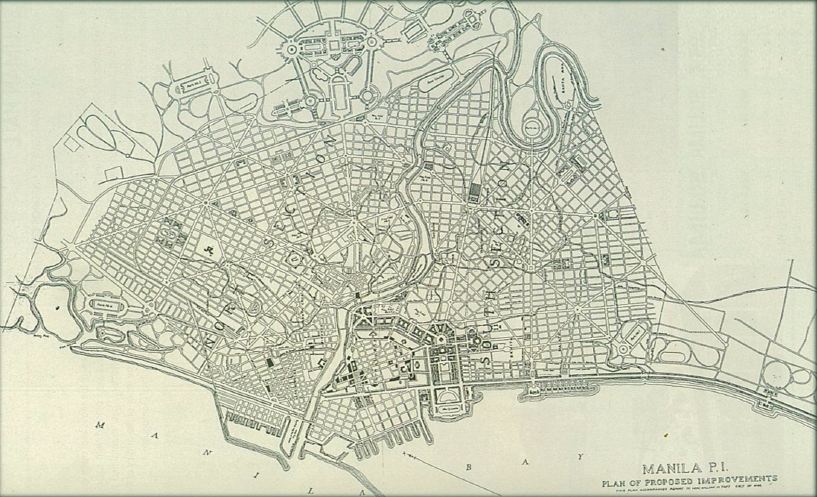

Rethinking art and empire inevitably brings imperial architecture and its colonial iterations to mind. After the Philippine-American War (1899–1902), Daniel H. Burnham won a commission from the US government to develop a master plan for Manila (fig. 2).5 Burnham promoted the City Beautiful movement popular in the United States from the 1890s to the 1920s, deploying urban planning and architecture informed by the European Beaux-Arts tradition as a means to generate civic pride.6 He had designed a plan for Washington, DC, before his Manila project, followed in turn by designs for Chicago and San Francisco. Like the plan for Washington, DC, the Manila plan had a central civic core with grand government buildings arranged in a formal pattern around a rectangular mall.7 Replicating the capital in the colony made US rule palpable. Burnham argued that “the gain in dignity by grouping these [government] buildings in a single formal mass . . . has been put to the test in notable examples from the days of Old Rome to the Louvre and Versailles of modern times. . . . Every section of the capitol city should look with deference toward the symbol of the nation’s power.”8 William E. Parsons spent almost nine years in the Philippines interpreting Burnham’s master plan. Parsons developed a hybrid architectural style that featured wide archways, shaded loggias, and porches, combined with Spanish colonial elements and local materials. Thus were imperial imaginaries of the metropole and the colony conceptually entwined, although formal and material localizations distinguished the latter.

Comparative studies of metropolitan expressions vis-à-vis colonial adaptations developed in the imperial diaspora could yield useful insights and new questions. In addition to architects, anthropologists, photographers, and artists were sent from the United States to the colonies or journeyed on their own volition. It would be interesting to trace continuities, ruptures, translations, and mutations from diverse geographic vantage points. For example, Parsons’s colonial buildings are an integral part of Philippine architectural history. What is their place in American art and architectural history? In the formerly colonized Philippines, architectural vestiges of US hegemony entwine contemporary notions of Filipino identity. What are the stakes for American art history and postcolonial identity in the United States? Pride in democratic principles must somehow be reconciled with this imperial past.

I return to the question of decolonizing scholarship: Who speaks for the silenced Other? If transcultural dialogues are to successfully address and redress inequalities of intellectual representation, thoughtful mediations are needed to communicate alignments and divergences of historical perceptions. Interventions may include, for example, provocative juxtapositions of counternarratives from opposing perspectives and geographies. Moving forward, corrective methodologies must consider the stifled voices and vexed identities of colonized cultures. Scholars from formerly colonized nations who expertly wield borrowed languages must impart why the granular matters by contextualizing data in theoretical frames that resonate with scholars at the center. The latter, in turn, must learn to value and fortify mastery of unfamiliar data, literature, and languages if they are to dialogue with or attempt to speak on behalf of others. Carefully designed collaborations among scholars of colonized and colonizing nations, such as what we initiated in the tri-continental, multi-author volume discussed above, are critical to discerning the contours of the complex interlocking shapes of the larger cultural cartography.

Cite this article: Florina H. Capistrano-Baker, “Inside the Outsider’s Gaze,” Bully Pulpit, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10066.

PDF: Capistrano-Baker, Inside the Outsider’s Gaze

Notes

- Kate Lemay and Taína Caragol, National Portrait Gallery, to Mariles L. Gustilo, Senior Director, Arts and Culture, Ayala Museum, December 21, 2018. ↵

- Lemay and Caragol to Gustilo, December 21, 2018. ↵

- Lemay and Caragol to Gustilo, December 21, 2018. ↵

- Transpacific Engagements: Trade, Translation, and Visual Culture in the Age of Empires, 1565–1898, ed. Florina H. Capistrano-Baker and Meha Priyadarshini (Makati City, Los Angeles, Florence: Ayala Foundation, Getty Research Institute, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz–Max-Planck-Institut, forthcoming 2020). ↵

- Burnham submitted the plan in 1905 to the United States Secretary of War, William H. Taft, who had served as the Philippines’ first civilian governor in 1901 and later became US President in 1909. “Daniel Burnham in the Philippines,” The Newberry Digital Exhibition, accessed Feb 26, 2020, https://publications.newberry.org/digitalexhibitions/exhibits/show/daniel-burnham-in-the-philippi/introduction. ↵

- Naomi Blumberg and Ida Yalzadeh, “City Beautiful Movement,” accessed May 12, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/City-Beautiful-movement. ↵

- Paulo Alcazaren, “Building a City Beautiful,” City Sense, The Philippine Star, July 5, 2003, https://www.philstar.com/lifestyle/modern-living/2003/07/05/212584/building-city-beautiful; Paulo Alcazaren, “The American Influence on the Urbanism and Architecture of Manila (1898–1952),” M.A. thesis, National University of Singapore, 2000; David E. Brody, “Building Empire: Architecture and American Imperialism in the Philippines,” Journal of Asian American Studies 4, no. 2 (2001): 123–45; Thomas S. Hines, “American Modernism in the Philippines: The Forgotten Architecture of William E. Parsons,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 32, no. 4 (1973): 316–26. ↵

- Annual Report of the Secretary of War (Washington, DC: US War Department, 1905), 632. ↵

About the Author(s): Florina H. Capistrano-Baker is Consulting Curator at the Ayala Museum, Philippines