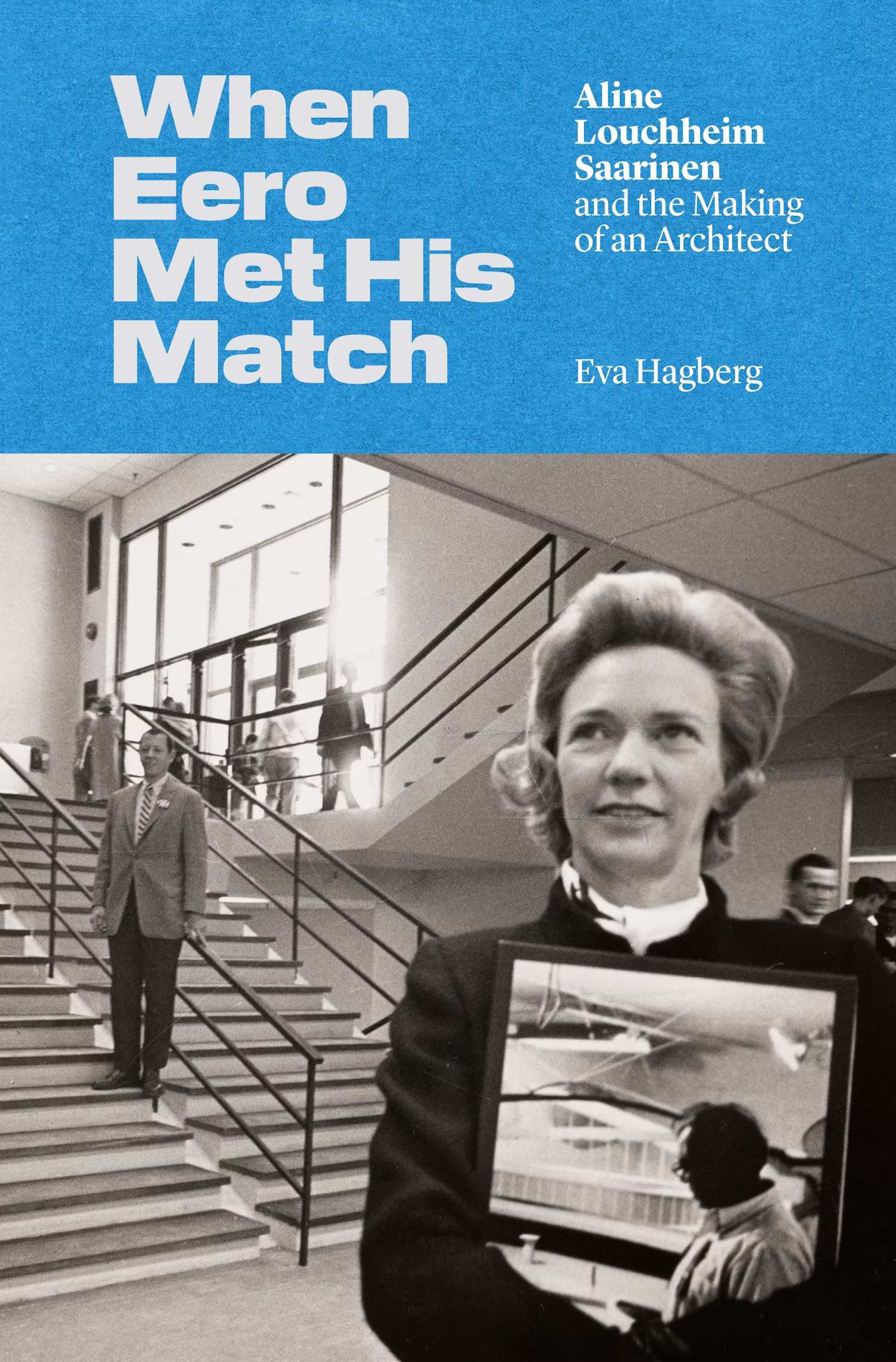

When Eero Met His Match: Aline Louchheim Saarinen and the Making of an Architect

PDF: Adams, review of When Eero Met His Match

When Eero Met His Match: Aline Louchheim Saarinen and the Making of an Architect

By Eva Hagberg

By Eva Hagberg

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022. 232 pp.; 35 b/w illus. Hardcover: $33.00 (ISBN: 9780691206677)

When Eero Met His Match is an extraordinary book for three reasons. First, it is about love and architecture. It is about pioneering publicist Aline Bernstein Louchheim Saarinen and her love for her second husband, the famous Finnish-born architect Eero Saarinen. It is also about the author Eva Hagberg, her love for Louchheim, for architecture, and for other figures in her life. Second, When Eero Met His Match is about women in architecture and how or why so many remain invisible. Louchheim was already a successful journalist when she met her future husband in 1953, but marrying him led to a new role in his firm with both benefits and liabilities. The relatively large number of women architects who have married other architects know this conundrum well. Third, When Eero Met His Match focuses on the role of language, rather than form, in the story of Eero Saarinen’s rise to fame. Saarinen’s buildings are known for their unique shapes—picture the Gateway Arch in Saint Louis or the TWA Terminal at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. To study them through word choices, headlines, letters, interviews, articles, books, and even obituaries is, to say the least, novel.

Hagberg chronicles the love stories in eight chapters, from the couple’s first meeting to beyond the sudden death of fifty-one-year old Saarinen from a brain tumor in 1961. Louchheim and Saarinen met in 1953 when Louchheim was already divorced, but Saarinen was still married. Both had children. Letters digitized by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art document with surprising frankness their romantic meetings and plans to be together. Hagberg illuminates how Louchheim imagined a position for herself at the firm in tandem with the architect’s plans to divorce his then wife, Lilian Swann, and remarry. On cue, in 1954, Louchheim gave up her position as associate art critic at the New York Times and moved to Michigan, becoming Mrs. Eero Saarinen as well as the “Head of Information Services” in her new husband’s firm.

Like her two protagonists, Hagberg loves architecture. She admits this in the first chapter, setting the tone for the book: “I realized that I do love architecture and have always loved architecture and that the project of this book was to explain a little bit about how it worked so that maybe we could somehow get back to just loving architecture” (21). Boldly, every other chapter recounts Hagberg’s own up-and-down recent experiences as a publicist for ten architects, mostly in California and New York. Hagberg’s life is uncannily shaped by the Saarinen drama that she is studying, just as her own circumstances inform her project. “We don’t talk much about how books actually are written into being, how they begin to announce themselves, first quietly and then loudly, and then how they take over the very interior of one’s mind,” she attests in a chapter about women in design (21).

During the course of writing the book, Hagberg divorces her husband, who is depressed and uninterested in architecture. By the epilogue—spoiler alert—she is in love again. “I would be his Aline, and he would be my Eero,” she tells us of her new beau (178). In a brief but powerful chapter, she opens up about loving an older male client. This love, she attests, is not romantic or platonic but rather based on their shared love of architecture, which she comes to fully realize only later, upon his death from cancer: “Lewis wasn’t my Eero, of course. But his death, and the way it impacted me, reminded me of how intimate and special these relationships can be” (155).

Such themes of intimacy, love, marriage, divorce, and death make the book a real page-turner. I basically read it in two sittings and spent the time in between plotting how to get back to it. Even in the chapters that focus on the Saarinens, the author pauses and addresses readers directly, almost like a letter or journal entry. The book also reminded me of certain films and television shows where characters speak directly to the audience or camera (such as Woody Allen’s Annie Hall or the NBC series The Office). Although Hagberg’s self-awareness might not appeal to everyone, it does make the reader feel part of the project, as when Hagberg notes that she is writing “on an August morning in a hotel room in Lower Manhattan” (20) or describes a time as “the week before an early draft of this book was due” (153). “It is time to meet our central actors from the past,” is how she opens chapter 2 (23). In this way, the book is about itself.

Despite Hagberg’s resistance to some academic protocols, the intellectual contribution of the book is noteworthy. Architectural historians have produced next to no scholarship on architects’ private lives. More significant, When Eero Met His Match tracks the role of the architectural publicist in twentieth-century America. Hagberg shows how Louchheim controlled all information about Eero Saarinen & Associates through her high-power network of editors, journalists, and photographers, “social mobility that she was born into/developed through her previous profession as an art critic” (65). Her position at the firm “helped to crystalize and solidify exactly what it was that Eero did” (162). For example, a major point in the book is that Louchheim is mostly responsible for the widely held perception of the TWA Terminal as a bird in flight. She understood, as a skilled writer, “how important metaphors could be to gently encourage an architecture-naïve audience to accept this surprising structure” (124). It is for this reason that most of us can easily picture the building.

The most sophisticated parts of the book are where Hagberg suggests that Louchheim occupied a zone of slippage in her roles as wife, widow, and publicist. For example, she sometimes had to feign amateurism alongside her considerable expertise. In her letters to Saarinen, she often adopts an advance-and-retreat strategy, according to Hagberg. Intriguingly, Hagberg also recounts how even today, in her work as a publicist, she needs to appear less organized and temper architectural insights with enthusiasm and femininity. At the end of the book, she says she sees Louchheim’s tactics everywhere, even in the ways her friends email her. So much for progress!

Hagberg’s focus on language in a field obsessed with form is another strong contribution. She analyzes in detail the layered correspondence that preceded the New York Times Sunday magazine article, for example, that Louchheim published on her future husband in April 1953. Chapter 8 is a standout chapter on language that traces the publicist’s role managing the communication of the news of Saarinen’s death. Hagberg tells us who found out what by cable and analyzes how the subtle word differences indicate changes in meaning. Some found out how he died, while others were told when. The cable to Alvar Aalto included the fact that Louchheim felt heartbroken. Hagberg insists these nuances were part of a sophisticated communications system : “She calibrated her performance of closeness so as to maintain the ties that she thought were most useful for Saarinen’s long-term reputation” (159).

My main quibble with the book is the suggestion that an autobiographical approach to a subject is largely without precedent: Hagberg says an intention of her book is to “revise the way in which many historians have done history” (xiii). I think of Dana Arnold and Joanna Sofaer’s inspiring collection on biographies and space from 2008.1 Or who can forget Katarina Bonnevier’s confession in her work on architect Eileen Gray: “I still have a need for heroines in architecture. And I have a crush on Eileen Gray.”2 Although the details of Hagberg’s project differ, the strong presence of an author’s voice (including her positionality) is a signature feature of much feminist and queer scholarship.

Overall, Hagberg’s When Eero Met His Match reminds us of the transformative power of love and the complicated legacies of those who dare to challenge convention. Through its pairing of personal narratives and archival analysis, the book not only enriches our understanding of architecture and its practitioners but also inspires us to reconsider the ways in which we perceive and engage with architects past and present.

Cite this article: Annmarie Adams, review of When Eero Met His Match: Aline Louchheim Saarinen and the Making of an Architect, by Eva Hagberg, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18999.

Notes

- Dana Arnold and Joanna R Sofaer, Biographies and Space : Placing the Subject in Art and Architecture (London: Routledge, 2008). ↵

- Katarina Bonnevier, “A Queer Analysis of Eileen Gray’s E.1027,” in Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction of Architext Series, ed. Jane Rendell, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden (London: Routledge, 1999), 165. ↵

About the Author(s): Annmarie Adams is an architectural historian at McGill University, Montreal.