Women Architects at Work: Making American Modernism

PDF: Hagberg, review of Women Architects at Work

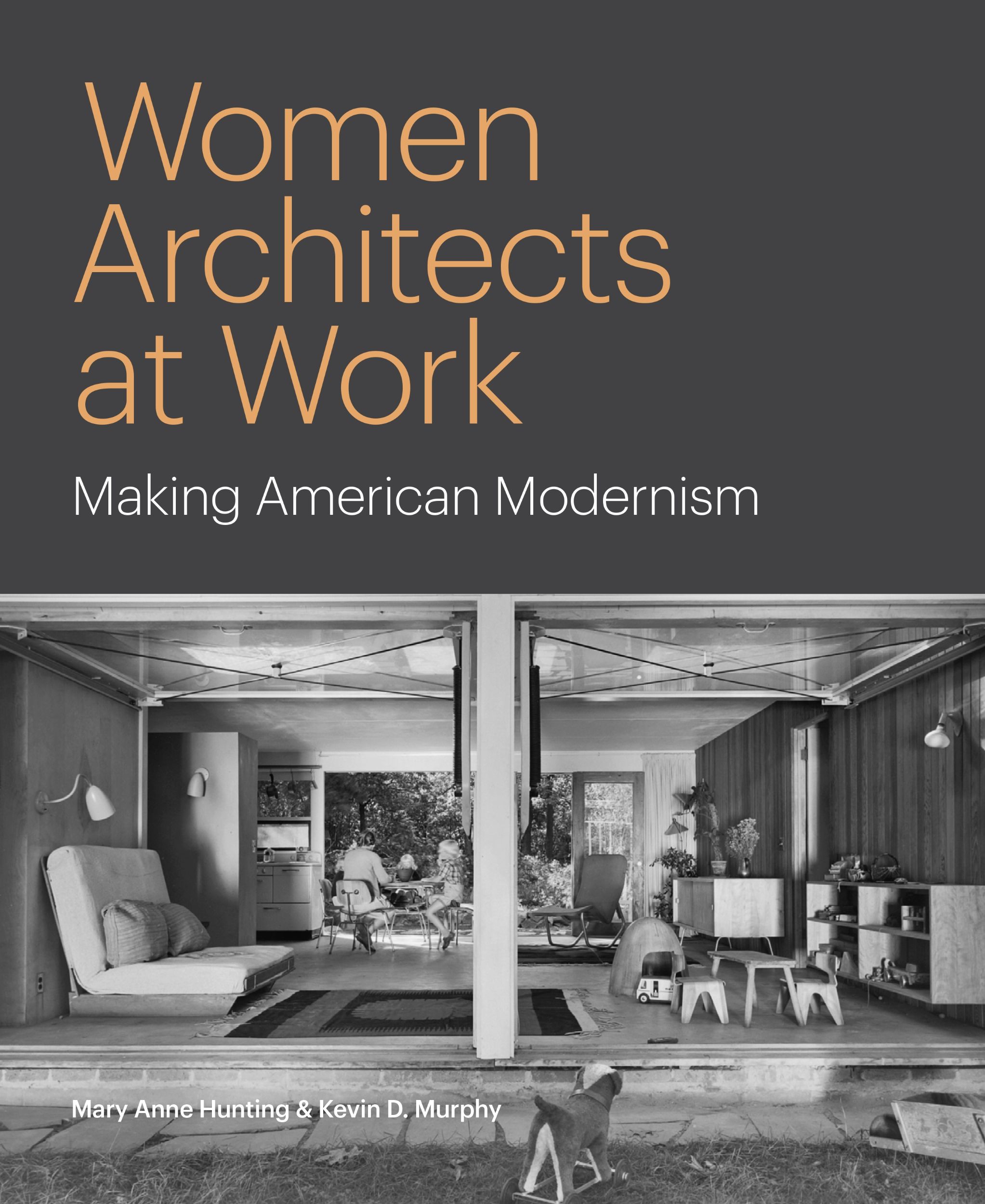

Women Architects at Work: Making American Modernism

By Mary Anne Hunting and Kevin D. Murphy

Princeton University Press, 2025. 272 pp.; 74 color illus.; 88 b/w illus. Hardcover: $65.00 (ISBN: 9780691206691)

In 2016, the architectural historian Despina Stratigakos published a slim yet remarkable volume called Where Are the Women Architects? Following the success of her participation in the 2011 launch of the themed toy Architect Barbie, Stratigakos’s book not only asked where the women architects were (among us, it turned out!) but also offered a framework for questioning the role historians, scholars, and fellow practitioners have played in the seemingly eternal mystery asked by her title.

That line of questioning is deeply felt throughout Women Architects at Work: Making American Modernism, a rigorously researched, exhaustively methodical book by architectural historians Mary Anne Hunting and Kevin D. Murphy. The text begins with the sentence: “Collaboration is at the heart of this book.” The remaining 207 pages (excluding notes) do a phenomenal job of demonstrating multiple modes of collaboration—between editors and architects, male bosses and female underlings, husbands and wives, designers and salespeople, and, fundamentally, women architects and other women architects.

The book is divided into eight chapters that each attempt to corral an astonishing amount of primary research. We begin with “Early Experience and Education,” emphasizing the role of the modernist-oriented Cambridge School of Architecture, and then move to “International Exchanges” and “Forging Networks” before shifting from a storytelling mode into a more analytical and interpretive one. Chapter 4, “Collaboration as a Primary Strategy,” outlines the necessity of many women to shoehorn themselves into some sort of collaboration with a man, whether that be a husband (as in the case of Aaino Marsio-Aalto), a boss (as in the case of famed SOM architect Natalie Griffin de Blois), or a mode of thinking (as in the dynamic and egalitarian The Architects Collaborative organized in 1945)—often a collaboration she may not have otherwise have chosen. The chapter “The Enterprising Spirit” showcases the work of women such as Alice Morgan Carson and Anne Tyng, while “Houses and Housing” explores the embrace of women as great theorists on housing, if not accepted architects. Chapter 7, “Creating Community,” moves beyond the Cambridge School and the big firms to explore the role of design in other types of places, like Sag Harbor and rural Massachusetts communities. The last chapter, “Singular Statements,” positions the work of female architects against the typical path of the male architect, arguing for a more nuanced understanding of why, at times, the lack of well-known female architects can appear like a tech-industry pipeline problem.

The structure of Women Architects at Work is propulsive, and its assembled facts are legion. Halfway through the book, Hunting and Murphy include three schematic illustrations of networks—“Educational Ties”; “Professional Ties”; and “Social Ties.” Featured in each diagram, as visualized by Scott Weingart, are figures such as Ethel Power, the editor of House Beautiful, whose role, many (including Hunting and Murphy) have argued, was critical to the acceptance of modernism in America. Another focus is Power’s partner, Eleanor Raymond, an architect who received a remarkable level of acclaim, largely due to Power’s attention. The two lived together, professionally and romantically, and appear to be at the heart of a remarkable network of women. Most notable, to this reader at least, is the relatively peripheral nature of many of the women whose names are more familiar. Anne Tyng, renowned for her collaborations with Louis Kahn, is diagrammatically depicted quite off to the side and disconnected, for instance, while names like Edith Cochran, Louise Leland, and Laura Cox occupy center stage.

If that seems like a lot of names, wait until you read the book. About halfway through, I made the note, “There are really a lot of people in this book!!!”—indicating Hunting and Murphy’s incredible skill at unearthing previously unheard-of women architects as well as their almost overwhelming and relentless drive to include everyone. “Networks, or contacts, were so ubiquitous and central to architectural practice in the mid-twentieth century that they have scarcely warranted comment in discussion of the profession,” the authors write (77). And yet, as they point out, it is precisely the dual lack of access to male networks and deep access to other women that is perhaps one of the stronger explanations for women architects’ incredible accomplishments and equally incredible lack of fame.

This brings us to the heart of the project. I will confess some skepticism about this book’s necessity when I was first asked to review it. I have seen, over the years, attention continually being brought—and seemingly just as quickly abandoned—to the often dismal plight of women in architecture. Books about women architects as a category abound, including: 100 Women: Architects in Practice; Women in Architecture: From History to Future; The Bloomsbury Global Encyclopedia of Women in Architecture, 1960–2020; Designing Women; The Women Who Changed Architecture; and, with perhaps my favorite title, Raising the Roof: Women Architects Who Broke Through the Glass Ceiling. However, I was delighted to see that my skepticism was unwarranted and that this book takes seriously not only its subjects’ lives and careers but the many structural issues they had to navigate as well. It showcases through its depth and thoroughness how many women architects have done truly pivotal work, changing not only their own immediate surroundings but architectural culture as a whole.

Chief among the challenges women architects have faced is that of the perception that women are inherently domestic. In wonderful moments throughout the book, Hunting and Murphy describe the ubiquity of the notion that women have an innate sense for the home and should contribute their intellectual effort accordingly: “Cultural and architectural critics claim that women in architecture have an innate sensibility for domestic architecture. . . a perception that evolved from the gendering of the home as female in the nineteenth century” (91). The authors also acknowledge the material realities facing women. Unlike the male architect Philip Johnson, who “designed and funded for himself” his first major realized house, women often had other, more pressing matters to attend. Ellamae Ellis League, for example, wrote of her own remarkable career: “I had an incentive you can’t beat; I had two children that I wanted to educate and it was up to me to make a living for them and raise them and just do it” (102). Meanwhile, Catherine Bauer Wurster, the extraordinarily accomplished urban planner, housing theorist, and wife of William Wurster, was described in a 1948 Museum of Modern Art press release as a “housewife, housing expert,” which Hunting and Murphy archly editorialize as “an incompatible description at best” (159).

This brings me to my minor quibble with the book, which is that I wish Hunting and Murphy had editorialized a bit more. Of course I understand the scholarly desire to let the evidence to speak for itself—and there is voluminous evidence in the text. Moments of real judgment and acutely shrewd commentary do appear throughout, dropped in around wry comments, like one from Elizabeth Cross Barnes, wife of Edward Larrabee Barnes, which is worth reproducing here:

It’s impossible to work on marriage and collect receipts, investigate gardenias, observe behaviors of pregnant women, think about the education of children, the margin of a house, gardening, holidays, and everything that I’ve been doing with half my mind and all my heart—and at the same time to work just hard enough to be paid (59).

As the book comes to a close, Hunting and Murphy begin to articulate its structure and argument, referring to it as a “group portrait”(193). They argue that oversight—the problem of people just not knowing enough about women architects—comes from the scholarly field of architectural history, in which “the preferences of scholars for certain kinds of life stories and careers are equally to blame: scholarly interpretations are preoccupied with artistic genius as well as with practitioners whose prolific output demonstrates a familiar pattern from early development to resolution, to a mature style, to late mannerism. This arc is seldom visible in the lifetime work of women architects, who typically lacked the patrons and hence the opportunities to design a string of buildings until they arrived at a signature style” (193).

The problem, then, is twofold. On the one hand, the material limitations hindering women have been structural: women have not been able to become architects because male architects and a male-oriented culture has kept them squarely in the domestic sphere, even when they have managed to get themselves into the architecture office. On the other hand, and as this book’s very existence makes clear, the issue is one of past attention: there was very little contemporaneous documentation, and when there might have been, it was not carefully preserved by large and well-funded institutions and instead relegated to dark closets or lost altogether. The architect Eleanor Raymond, thinking presciently, created her own archive before her death, which may be why her life is so much more easily analyzed today. Others had to be discovered through less straightforward methods. Hunting and Murphy point out the value of scrapbooks, a culturally accepted method for women to create something approximating an archive. But structural issues remain. Most of these women’s papers, unlike those of Eero Saarinen, Paul Rudolph, or Philip Johnson, were not collected by major educational institutions and therefore not deemed “worthy” of study. The question this book could pose now is: are women architects today acknowledged and documented any better?

The book is not a polemic; rather, in its almost overwhelming firehose of information about the many women who worked in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and were central to the project of “making American modernism,” as the book’s subtitle indicates. Yet it is also a subtle indictment of twentieth- and twenty-first-century architectural culture and the constricting narratives that remain around the roles of women.

This book is well worth reading and stands out from the crowded field of books about architecture with “women” in the title due to its specificity, clarity, wealth of research, and narrative propulsion. It fits well within a nascent “feminist canon,” if we can call it that—a series of books that includes Stratigakos’s Where Are the Women Architects?; Alice T. Friedman’s groundbreaking 1998 book Women and the Making of the Modern House; and Almost Nothing, Nora Wendl’s newly published and phenomenal biography and analysis of Edith Farnsworth. Hunting and Murphy’s contribution is more wide-ranging and sprawling than these others, but the sheer volume of research, documentation, and close analysis of so many women architects and their work demonstrates that it is, in fact, still possible and necessary to write a new history of this topic. I await the day, perhaps decades in the future, when we will be asked to read Men Architects At Work. In the meantime, Women Architects at Work will serve us well.

Cite this article: Eva Hagberg, review of Women Architects at Work: Making American Modernism, by Mary Anne Hunting and Kevin D. Murphy, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 2 (Fall 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.20519.

About the Author(s): Eva Hagberg is an independent scholar based in Los Angeles.