An Interview with Art Educator Professor Johnnie Mae Maberry, Tougaloo College

Author’s note: Johnnie Mae Maberry is my mother. I have the privilege of being not only her daughter but also her student during my tenure at Tougaloo College. The interview is set as a more in-depth conversation than my previous interview with her in 2015, discussing the teaching training of African American female art educators from Historically Black Colleges.

Tougaloo College is a small private liberal arts institution located in Tougaloo, Mississippi. It was founded in 1869 on a slave plantation and is one of Mississippi’s oldest Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Tougaloo, like many HBCUs, is the alma mater of renowned African American professionals, including artists, art historians, professors, and curators. Professor Johnnie Mae Maberry, who has been teaching at Tougaloo College since 1989 as the first female African American art educator at the institution, also graduated from Tougaloo with a bachelor of fine arts degree in visual arts in 1970 (fig. 1). Throughout her career, she has traveled the world exhibiting her artworks, and her Slave Narrative series was featured during the PBS syndication of Slavery in America. I interviewed Professor Maberry to discuss her teaching practices, professional roles, experiences, and obstacles as an African American art educator at an HBCU.

Lynnette M. Gilbert (LG): What is your current title at Tougaloo College? And what other positions have you held?

Johnnie Mae Maberry (JMM): My current title is associate professor of art with tenure. I am also codirector for the Institute for the Study of Modern Day Slavery; those are the two titles that I presently have there. Other positions that I have held include the curator of the Tougaloo College Art Collections, the director of the Tougaloo Art Colony, and the chair of the art department.

LG: Can you tell us about modern-day slavery and how that relates to art and art education?

JMM: The Institute for the Study of Modern Day Slavery is a program funded by the Andrew Mellon Foundation, and we are now in our fifth year. We received a second round of funding. The purpose of the Institute for the Study of Modern Day Slavery is to educate students about the existence of modern-day slavery [MDS]. Tougaloo College is the first HBCU to establish an institute that addresses modern-day slavery. Some of the things that fit under the category of modern-day slavery include mass incarceration, human trafficking, sex trafficking, and organ trafficking.

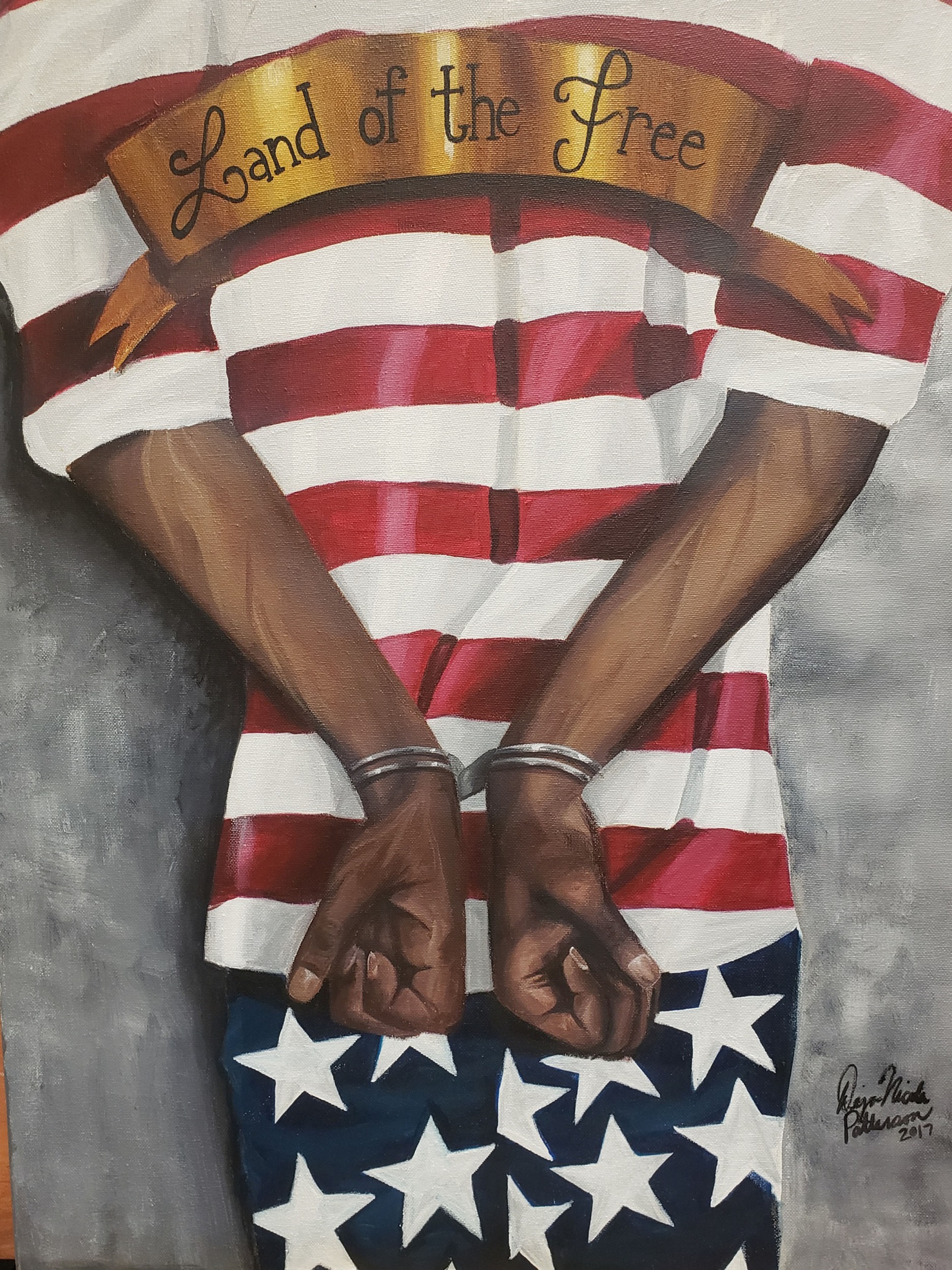

Art is a vehicle for raising awareness, and some of the projects I have facilitated include the Red Sands Project [fig. 2], which uses site-specific earthworks to draw attention to the arbitrary nature of geopolitical borders and the ways in which they divide communities and make individuals more vulnerable to trafficking. I’ve also worked with students to get them involved with creating works of art based on their research of MDS [fig. 3].

LG: Can you tell me how the art program has changed during your tenure at Tougaloo College?

JMM: The program has gone through many changes. During my early years here, I was instrumental in adding new courses to the curriculum [in both painting and drawing], in addition to adding a printmaking course, changing the description for the Principles of Art Education course, reactivating the African American Art History course, and bringing in a Research in Art course. I’m sure there are some other things that I may be missing. The Tougaloo Art Colony was also instrumental in helping us gain more space for the art department. For instance, through the Tougaloo Art Colony, we got a printmaking studio and a more developed ceramics studio. Those were some major changes that happened early on in my tenure as a professor here.

LG: Of those courses you just mentioned, how many have you taught, and what courses are you currently teaching?

JMM: I’ve taught African American Art, and I’ve also taught Principles of Art Education, and I teach all the printmaking, painting, and drawing classes. I also teach the research classes.

LG: Can you discuss some of your teaching methods? It could be in any of the courses you’ve mentioned, and give some examples of assignments you’ve given your students.

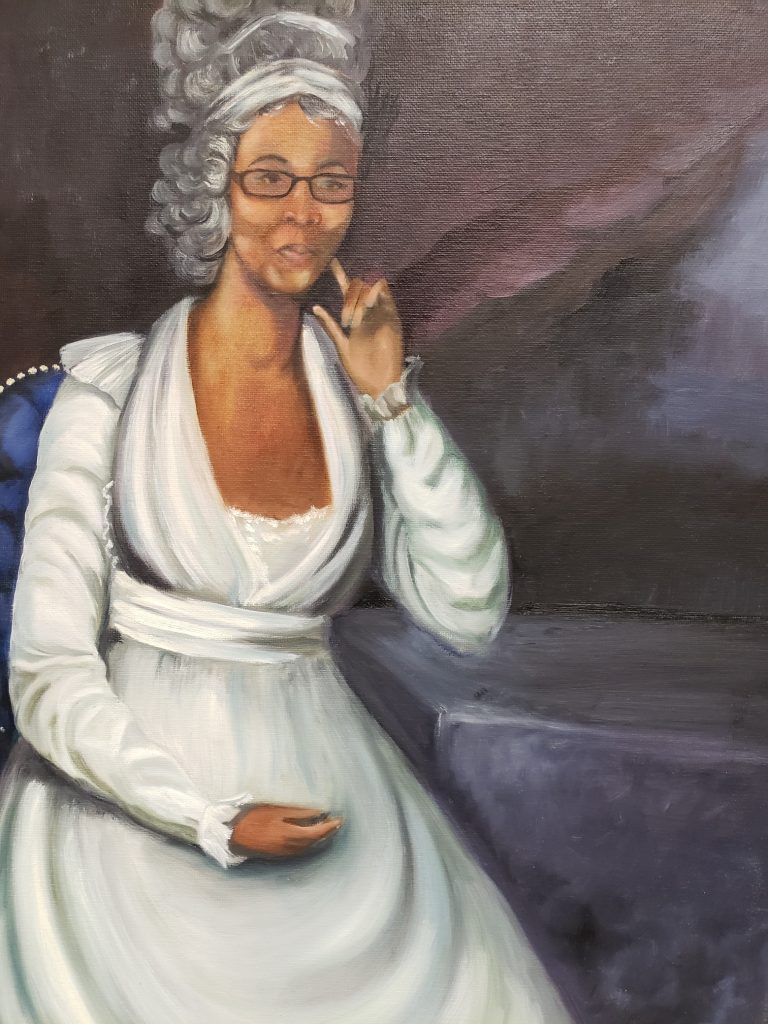

JMM: In my African American Art History class, I introduce students to artists like Joshua Johnston (Johnson), Robert Scott Duncanson, [and Edward Mitchell] Bannister. These are 1800s artists, so I help my students understand that artists during that period used a different kind of palette, especially when we talk about Joshua Johnston. Most people didn’t know that African American artists even existed during the nineteenth century. To help them understand [I let them know that] bright colors like cadmium red and cadmium yellow did not exist yet. We would have a drawing of numbers, and the student whose number came up got a chance to pose as a Joshua Johnston model [fig. 4]. I would lay out a palette of the colors, oil colors that would be very similar to the color palette of Joshua Johnston, and paint the student in the style of that particular artist [fig. 5]. So, students can understand different styles of the period and the uniqueness of the work. There was always an object held in the hand of the person who modeled; the figures look rather rigid; and the young children look like older adults . . . these are the kinds of things that they were able to take note of, to make the artist more memorable to them. Through this teaching method, students learn that even during slavery there were African Americans who produced art equal to, if not better than, the work of white artists.

In another assignment, I ask the students to create quilting patterns as they study the work of Harriet Powers. Powers could not read or write, but she did biblical story quilts. In order to help my students understand the process of a folk or intuitive artist, I use Harriet Powers’s quilts as an example. Her quilts became kind of a messaging mechanism to communicate among enslaved people. This was a way of letting people know about the underground railroad, creating an escape pattern, but she was more known for her biblical quilts. She was a woman who could not read, could not write, but she was able to produce quilts that pretty much told the story of the beginning of Creation from the Bible.

LG: Can you give an example of teaching methods in one of your studio courses?

JMM: One example of teaching methods in my painting class. . . . It should not come as a surprise to you that most of the students who enter a freshman painting class at the college level haven’t had any art exposure whatsoever. They just know that they like art . . . very seldom do I have a student who has had art courses or the foundational knowledge needed to move to a more advanced stage right away. The first thing I do, I emphasize color theory, no matter the student’s level of color knowledge. We begin with the basics of primary, secondary, and tertiary colors and color schemes, but instead of having them create a chart, a study chart of red, yellow, blue, that kind of thing, I make it more exciting. They have to create a nonrepresentational painting using only the primary colors and mixing to get the secondary and tertiary colors [fig. 6a, b]. They have to use several shades of primary red, several hues of primary blue, several hues of primary yellow, and they’re not allowed to bring in any premixed colors at all. So, within that prescription, they sketch several nonrepresentational compositions before they even start to paint. We discuss how to create a good composition during the sketching process and which design principles can be utilized to create an aesthetically pleasing and balanced composition. We talk about how compositions are done, and that even when it’s abstract or nonrepresentational, there must be harmony, balance, and unity within the work. We are using the language of art throughout the whole process.

They are given the definitions, allowed to ask questions, and shown that they understand the application of the language of art when they create their first painting, which is also a color-mixing exercise. Still, they end up with a complete painting that’s frameable. The first painting surprises them; “Oh, I didn’t know I could do that!” Yeah, you can do that!

LG: During our previous interview in 2015, you shared that many of your students graduated with a degree in visual arts and became practicing artists and art educators.1 Could you give me some examples of who they are and their current positions?

JMM: We always start with you, Dr. Lynnette Gilbert, a professor at Arkansas Tech [BA in visual arts, 1997]. You’ve received a doctorate and continued to stay in art education. You have also helped write programs and curriculum for high schools in Tennessee and still work with curriculum development. Then we’ve got—I’m going to name the educators first—LaKeitha Bassett [BA in visual arts, with an emphasis art education, 1998], who is also an art educator. She earned a master’s degree in art education. I believe she is doing great things now in Houston as a high school art teacher. Then, there are others who I’m trying to think of the names right now. Oh, Felicia!

Felicia Wolfe [BA in visual arts, 1993] was one of the first art students to become my mentee in 1990. Although I only taught her for about a year before she graduated, we have developed a longtime friendship and a collegial relationship. Felicia began her career as a high school art teacher in charge of the IB [International Baccalaureate] art classes. She is now director of the IB program at one of the local high schools. She continues to create art. The art educators who graduated from Tougaloo continue to produce and exhibit their work.

I also mentored students who did not major in art. At the ninth hour, such students decided to enroll in enough art courses to enter graduate art programs. Torkwase Dyson [BA in sociology and double minor in social work and visual arts, 1996] is a renowned national and international artist. She was one of those students. She recently received an honorary doctorate from Tougaloo College.

Deja Patterson [BA in visual arts, 2017] was awarded an internship at the Louis Armstrong Museum. She also worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and participated in a group show there. She continues to exhibit her work and has quite a following. Deja also earned her MFA at Queens College [New York, 2020]. Sidney Conley [BA in visual arts, 2012] is an internationally known photographer. Ingrid Larkin [BA in visual arts, 1994], whose graphic arts and design skills led her to the Johnson Publishing Company, of Ebony and Jet, became one of their head graphic artists before leaving that company. Oh, yeah! Earnest Davis [BA in visual arts, 2016] just recently received his MFA [from Mississippi College in 2021]; his genre is Afro-punk and futurism.

LG: Wow, that’s an impressive lineup. What relationship do you have with the Tougaloo College Art Collections?

JMM: My relationship with the Tougaloo College Art Collections goes back to my time as a mentee of the founder of that collection, Professor Ronald Schnell.2 He was passionate about ensuring that his students were exposed to original artworks and artists of all nationalities. Within the collections, we’ve got art made by people from Africa, Europe, China, Japan, and all across the United States. It is a collection that’s culturally rich with diversity.

My relationship with the collections is almost like that of a parent and child. When Professor Schnell was no longer [in charge of] the collections, he ensured that anything relevant to the collections needed to be held onto; so he sent me a copy of it. So, fortunately, I have a list of the works that are in the collections. Even when I was not the curator of the collections, I was being sought out to help send works from the collections, such as Romare Bearden’s work, which was featured and exhibited in other states. There were a couple of pieces by Bearden in the collections, and I was contacted by the High Museum [in Atlanta]. They were doing a retrospective of Romare Bearden’s work [in 2015]. I negotiated all of the necessary parts needed to ensure they received his work, that it was insured and returned, and that all the proper paperwork was signed. His work traveled for several months, and then it was transported back to the college in an eighteen-wheeler. . . . It was shipped to the High Museum and then returned to Tougaloo, all under my watchful eye.

As a curator [of the collections from 2014–18], I was excited to learn that the Benny Andrews Foundation, through the Negro College Fund, was donating Andrews’s works to HBCUs. Each HBCU would get either one or two pieces. They gave us three! Being present to receive the works by Andrews was a memorable experience in itself.

For years my connection with the collections was sharing the collections with my students. When the works hung in the library, my classes always went over to study particular pieces and talk about the artist and their style. What could they borrow that would help to enhance what they do? In 1998 the works were moved from the library into temperature-controlled storage. The collection was in storage for more than ten years. Eventually, the college constructed the Bennie G. Thompson Building (2013), which contained a temperature-controlled art vault.

LG: How many pieces are in the collections?

JMM: It is difficult to give an accurate number. My estimate is 2,500 [including the African and Oceanic works . . . without those works], it’s about 1,500. It is unfortunate that I am unable to give an accurate or definite number.

LG: Were the collections displayed anywhere else after they moved out of the library and into storage?

JMM: The president [at the time, Dr. Beverly W. Hogan,] had many African American pieces from the collections hanging in her house as decoration. Some of the most valuable African American art pieces were hanging in her house. She had John Biggers, Bearden pieces . . .

LG: Catlett?

JMM: That’s right, Elizabeth Catlett. Some of the most important pieces were hanging in the president’s house. So, I began to get permission to bring my classes into the president’s house and tour the work there.

LG: Did you create the catalogue for the president’s house?

JMM: I did not create the catalogue. Jane Hearn created it. [Editor’s note: Hearn, an affiliate of the art program, was the founder of the Tougaloo Art Colony.] I was, however, able to utilize it when showing my students works that were featured in the house.3

LG: We talked about how you took your students to the library and then later to the [president’s house] as part of your teaching. Have you used the collections as a tool for teaching in other ways? For example, did you only take your African American Art class or did you take all of your classes?

JMM: All my classes. When I was not teaching Principles of Art Education, the adjunct teacher would take her students over to discuss different aspects of the language of art, art appreciation, and the different styles represented within the collections. In addition, I took my printmaking class to see the collections and conducted tours with different tour groups so many could enjoy the collections. For example, Tougaloo College hosts a Summer Art Explorers art camp. As part of the camp, students and classroom assistants participate in the Tougaloo College Art Collections scavenger hunt [fig. 7]. The Tougaloo Art Colony also regularly tours the collections [fig. 8]. These are great ways to share the collections with the wider community.

LG: Could you talk about how your art practice was influenced by your engagement with the Tougaloo College Art Collections?

JMM: My art practice and how it has been influenced through my engagement with the collections is varied. It was such a blessing to walk among the works, handle the works, and see the different styles of the artists while trying to process the meaning behind the works. I became bolder and began to step away from the traditional ways of producing my work. My exposure to the collections as an overseer of the collections has enhanced my development as an artist, as well. I have gained more purposefulness in what I create and why I create. Now, I’ve always said that artists have a big responsibility. Our responsibility is probably greater than most folks, because we can teach lessons that people don’t learn unless they see it. Having a relationship with the Tougaloo College Art Collections taught me many lessons. I can teach those lessons through my visual art as well.

LG: Would you say that sentiment extends to your teaching as well?

JMM: Absolutely. I say so many times to my students that our gifts come with responsibility. Our responsibility is to develop our gifts to their fullest potential. By doing so, we show our appreciation of our gifts and honor the Gift Giver. Artists’ responsibilities go beyond service to the self. Through our art, we can present a vision of a better and more loving world.

LG: Could you tell me some obstacles you have experienced being an African American art educator?

JMM: Being an art educator at an HBCU, I think the biggest obstacle is administrators who do not have an appreciation of or knowledge about art. So the art department itself, it’s not valued as much as other departments. It does not get the funding that other departments get or the administrative support. At Tougaloo, there are art classes in basements of various buildings. We are scattered across the campus. This happens when you don’t have the support needed. Even if you have a really valuable art collection, like we do, things begin to crumble. So, the appreciation level dwindles even more with each new administration. Each comes with even less knowledge than the former. And so now we’re dealing with the possibility of Tougaloo not even offering an art degree. I have not gotten a final word, but that’s one of the things that this new administrator is entertaining. [Editor’s note: In August 2021, Tougaloo College decided to close down its art program, and this is reflected in the Tougaloo College’s Visual and Performing Arts webpage.4]

LG: If Tougaloo closes the art department, what does that mean for the art education program?

JMM: I don’t know. See, that’s the thing. Nothing—nobody’s communicating much of anything to me, but I would think that if you’re not offering an art degree, what happens with art courses, what happens with the courses that the students in art education need, what happens to the art education degree? I did ask the question about the art education degree when I communicated with the president in response to an email about my employment status and the status of the art program. I still have not gotten a response.

LG: Switching gears, could you tell me how Tougaloo fits within the larger context of HBCUs and African American art?

JMM: Tougaloo fits within the larger context of HBCUs and African American Art because of the Tougaloo College Art Collections and the African American artists that are part of the collections. It contributes not only to the cultural knowledge of Tougaloo’s students, but it also enriches what the state [of Mississippi] has to offer the world about African American artists. The Tougaloo College Art Collections also contains one of the richest African and Oceania art collections in the state.

LG: I know that the Institute for the Study of Modern Day Slavery has evolved into a partnership with other HBCUs, including Clark Atlanta and Huston-Tillotson. It seems like partnerships between HBCUs are crucial to preserving the history and legacy of these programs. What are your affiliations with other HBCU organizations such as the NAAHBCU [National Alliance of Artists from Historically Black Colleges]?

JMM: I am affiliated with the NAAHBCU as one of its original members. Through the NAAHBCU, art educators associated with HBCUs participate in group exhibitions across the country. We have also been able to exhibit in other countries. Most recently we exhibited in five different venues in India. I traveled to India in January 2020 to open our first exhibition and participated as a panelist. We are now in the process of documenting the history of the NAAHBCU and its members to preserve our legacy.

I’m also a part of the Alliance of Museums and Galleries from HBCUs led by Dr. Jontyle Robinson and Dr. Carl McFarland. Through this alliance, we introduce students to careers in art conservation and preservation where students of color are underrepresented. Since 2017, HBCU students have participated in conservation and preservation workshops through Yale and Princeton.

LG: Is there anything else you want to mention regarding this topic before concluding the interview?

JMM: I would like to mention that it’s critical that HBCUs guard their collections and continue to hold on to their departments, and that HBCUs should probably do training for administrators to understand more about the importance of art: its preservation, representation, and value to students of all ages.

Cite this article: Lynette M. Gilbert, “An Interview with Art Educator Professor Johnnie Mae Maberry, Tougaloo College,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12527.

PDF: Gilbert, Interview with Johnnie Mae Maberry

Notes

- Lynnette Gilbert, “Beneath the Hanging Moss: The Journey of African American Female Artist/Educators at a Historically Black College” (PhD diss., University of Houston, 2017). ↵

- Turry Flucker, “Tougaloo Art Collections,” Mississippi Encyclopedia, originally published January 24, 2020, https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/tougaloo-college-art-collection. ↵

- Jane Hearn, “Tougaloo College Art Collection President Residence Gallery Guide,” 2005. ↵

- “Tougaloo College Department of Visual and Performing Arts,” Tougaloo College, accessed August 31, 2021, https://www.tougaloo.edu/academics/divisions/humanities/department-visual-and-performing-arts. ↵

About the Author(s): Dr. Lynnette M. Gilbert is Professor of Fine Arts at Arkansas Tech University