The Art of Flocking: Sapphire and Crystals, Education, Community Building and Collaboration

There is an art to flocking; staying separate enough not to crowd each other, aligned enough

to maintain a shared direction, and cohesive enough to always move toward each other.

—adrienne maree brown

This quote by adrienne maree brown 1 provided the title and inspiration for the Chicago Park District’s summer 2018 program, The Art of Flocking: Cultural Stewardship in the Parks, which engaged 2,500 youth and their families through 215 public programs and exhibitions to explore the histories and legacies of Mexican American artist Hector Duarte and Sapphire and Crystals, Chicago’s longest-standing Black women artists’ collective.2 These words come from brown’s 2017 book Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds in which the pleasure activist frames her vision for collaboration and societal change through the writing of Octavia Butler, biomimicry, and civil rights histories, specifically emphasizing how small actions and connections among people can lead to the creation of a more just and liberated future.3

brown’s concept of “flocking” aptly describes Sapphire and Crystals’ collective work since they were founded in 1987 (fig. 1). While each member maintains a professional and individual career, they mentor one another, promote Black women artists through their exhibitions, and foster an appreciation of the Black Arts Movement (1965–75) through teaching, creating public artworks, and encouraging younger generations of artists. This article explores how Sapphire and Crystals’ emphasis on education, community building, and collaborative practice helps establish new artistic networks for Black female artists and youth in Chicago, which also counters the erasure these groups have historically experienced within mainstream art institutions.

The Art of Flocking

The Art of Flocking summer program connected students to the work of “Chicago artists with deep commitments to social justice, cultural preservation, community solidarity, and structural transformation.”4 Sponsored by the Chicago Park District and the Terra Foundation for American Art, the program was designed for children from the ages of three through fourteen and held at city parks on the city’s North, West, and South sides.

Sapphire and Crystals’ member Juarez Hawkins was among the teaching artists who designed the Art of Flocking curriculum to cultivate Black and Latinx children’s understanding of their own cultural lineage and ancestry and to explore questions of migration and immigration, resistance and healing, and personal and structural transformation.5 ArtSeed teaching artist Asusena Martinez explains that art classes in schools generally promote European artists as artistic models, such as Picasso and Van Gogh: “You don’t always get the opportunity to learn about Chicago based artists . . . especially people of color.”6 Maria Ambriz, a fellow teaching artist, emphasized how the program taught students that art could be a tool for community transformation, undermining the frequent feeling that “we don’t have control in our surroundings.”7

The curriculum featured exercises that were directly informed by the artists of Sapphire and Crystals and other Chicago-based creators. The session “The Sculptor and the Clay” introduced the performance art of Candace Hunter and asked students to role-play possible solutions to problems plaguing communities today. “Remembrance” was inspired by the work of Hunter, as well as Marva Lee Pitchford Jolly (1937–2012) and the altars created by Sapphire and Crystals, as a way for children to consider who their ancestors are and what family histories they honor. “Fluid Existence/Migration” contemplated parallels between bird migration and depictions of memory and heritage in the art of Joyce Owens, Duarte, and Jolly. “Transformation” prompted students to collaboratively construct a photograph that represents themselves and their neighborhood after viewing works by Rose Blouin, Pearlie Taylor, Sandy Skogland, and Leonard Surayajaya. “Sanctuary” used Hawkins’s abstract Perceptuary sculptures and images of insect and animal nests as models for children to define how they understand their own homes and sanctuaries. “Weaving Connections” responded to the work of Felicia Grant Preston and Victoria Villasana by exploring how art can create bonds among people. “Transformation through Power Objects” examined how children can transform themselves by creating tools made from found materials and recycled objects after considering the work of Rhonda Wheatley, Shahar Caren Weaver, and Cyrus Kabiru. “Sankofa” encouraged students to employ the West African Akan iconography frequently used by Dorian Sylvain and Arlene Turner-Crawford in conjunction with Duarte’s use of mariposas, or monarch butterflies, to address the histories of both the Great Migration of African Americans and Latinx migration.8

The youth enrolled in the summer program also benefited from one-on-one conversations with several members of the collective. Participant Josseline Canas stated, “All these artists I met inspired me to do more art and to be something I couldn’t imagine I would be,” and she cited talking with Turner-Crawford, in particular, as empowering her to continue her pursuit of life as an artist.9 When Turner-Crawford was in third grade, she had a similar encounter with Dr. Margaret Burroughs (1915–2010). Burroughs had helped establish the South Side Community Arts Center (SSCAC), the oldest African American art center in the United States; cofounded the DuSable Museum of African American History; and mentored several generations of young artists in the city of Chicago.10 Burroughs had asked Turner-Crawford, “Oh, you like art?,” and then advised, “Start seeing yourself doing it, start dreaming about it, start visualizing yourself doing it.”11 The power of these interactions cannot be underestimated. As brown argues, “What we practice at the small scale sets the patterns for the whole system.”12

A Brief History of Sapphire and Crystals

Following brown’s premise, Sapphire and Crystals’ dynamic network of Black women artists began with a simple question when Jolly, cofounder of the collective with Grant Preston, asked a friend and fellow artist in 1986, “Who and where were other Black women visual artists?” After a momentary pause, they were able to name only seven artists, and they were both included in the count.13

Jolly raised this question just as her clay artists’ collective at Mudpeoples Studio, established in 1983, was coming to an end.14 At this moment of transition, Jolly and Grant Preston considered how they could expand and continue the important conversations held in the Mudpeoples Studio for a broader community of Black women artists. They decided to invite a group to discuss the possibility of an exhibition, which resulted in their first show, entitled An Exhibition of Black Female Artists in the Chicago Area held at SSCAC.15

The success of this 1987 exhibition prompted the group to organize formally as a collective, and thirty-four years later, Sapphire and Crystals continues to thrive. Composed of a group of between fourteen and twenty Black women artists at any one time, the group recognizes that art production often comes second to their full-time jobs and that living in the Midwest means garnering less attention from the art market than their peers do in New York or Los Angeles.16 Here Sapphire and Crystals continues the work of the League of Black Women, which formed in Chicago in 1971, in their words, “to seek solutions to the cruel sufferings thrust upon us by society’s double indictment—the cross of being Black and the burden of being female.”17 In 1974, the league formed a curatorial committee, comprising Barbara Jones-Hogu, Yaoundé Olu, Shirley Sullivan, and Betty Wilkins, in order to sponsor exhibitions of Black women artists, including Fem-Images in Black held that October at SSCAC, thirteen years before Sapphire and Crystals’ first exhibition there.18 Sapphire and Crystals also builds on the work of Burroughs and Olu, who ran the Osun Art Center from 1968 through the early 1980s.19 Both Burroughs and Olu later exhibited with Sapphire and Crystals, exemplifying the collective’s commitment to paying respect to their elders, intergenerational dialogue, and uplifting all Black women.20

The name “Sapphire and Crystals” pays homage to strong Black women as well as the growing spiritual consciousness of Jolly and Grant Preston during the late 1980s.21 Owens notes that crystals also suggest precious or hidden gems, highlighting the talented Black female artists who have been overlooked for too long.22 Blouin adds that sapphire references the stereotyped character of the pushy Black woman from the old Amos ’n’ Andy radio and television show, explaining that the group reclaimed “Sapphire as an empowered woman who stood up for herself and crafted her own destiny, ideas which were consonant with our objectives as artists.”23

Painter Emma Amos’s words from 1982 would likely resonate with Sapphire and Crystals’ members at the time of their formation: “Don’t complain about being a black woman artist in the 1980s. Many people both black and white think you were fashioned to fit the slot in a turnstile—a mere token baby.” Instead, Amos advocates, “Do exhibit with people whose work you like and in which you find similarities to your own. . . . Your peers are the people who see your work as it’s happening. They give you feedback and keep you going.”24 Amos’s call to cultivate one’s artistic networks is the core philosophy of Sapphire and Crystals. Unlike other women artists’ collectives, Sapphire and Crystals chooses not to operate a physical gallery space and frees members to focus on developing their professional careers and mentoring one another. Relief from monthly membership fees and the obligation of maintaining a gallery also allows Sapphire and Crystals to remain active in community-based art projects and programs, which frequently support underserved populations in Chicago.

Mentoring and Building Careers

Grant Preston explains that the members of Sapphire and Crystals join the group at very different stages of their careers and possess varied levels of professional experience. When she founded Sapphire and Crystals with Jolly, for example, Grant Preston’s experience at that time involved mainly exhibiting in student shows and local art fairs.25 Sapphire and Crystals decided with their first show that essential tasks would be equally distributed, including taking meeting notes; managing the budget; overseeing the production of catalogues, press releases, and invitations; proofing and editing artist statements; and curating and installing the show.26 Members apply the skills learned through their collective exhibition practice to advance their own artistic careers, whether as an artist or curator. Makeba Kedem-DuBose, for example, attributes the development of her curatorial methods and philosophy to Owens’s mentorship. Owens shared her extensive knowledge of curating for both Sapphire and Crystals and Chicago State University, prompting Kedem-DuBose to earn a curatorial certificate from the University of Chicago’s Graham School in 2017.27

Less tangible than transferable skills but equally important are the conversations among members and group critiques that occur while preparing Sapphire and Crystals’ exhibitions. During these informal meetings, members are not afraid to challenge each other to produce their best work. As brown asserts, collaboration requires humility and a willingness to listen in order to learn from one another.28 Renee Williams Jefferson describes the group’s meetings at Jolly’s studio as sites of phenomenal support.29 Blouin stresses how Sapphire and Crystals’ members inspired her to consistently produce exhibition-worthy photographs, even though she was working full-time and single-parenting two children.30 Artists who joined Sapphire and Crystals in later years emphasize how mentorship by more experienced members transformed their art. Taylor comments, “Just being present in the collective made me think about the importance of creating art and that I should have a voice in the direction in which I want my work to take.”31 Wheatley adds, “The support of people like Joyce Owens, the late Marva Pitchford-Jolly, Juarez Hawkins, and Felicia Grant Preston made me feel more comfortable taking risks and pushing myself to actually try the new, experimental ideas I sketched out but may have otherwise not pursued.”32 The relationships Kedem-DuBose established with fellow members resulted in introductions to notable commercial galleries and universities, where she exhibited her work and expanded her client base at the same time, countering her grandmother’s earlier warning that “there was no room for a Black female artist in the world we lived in.”33

The Art of Sapphire and Crystals

Just as in brown’s definition of the art of flocking, members of Sapphire and Crystals share direction, specifically in creating greater visibility for Black women artists, but they do not demand a unified aesthetic. Not all the members of Sapphire and Crystals can be addressed here, but the following examples demonstrate the wide range of artistic practices found in the collective.

Artworks by Grant Preston, Taylor, and Patricia J. Stewart all invoke spirituality and transformation through a variety of media. Influenced by the beautiful and colorful sunsets of the Caribbean, Grant Preston’s nonobjective paintings, such as Remnants of a Dream (fig. 2), try “to reach for and chase after this feeling of being in the presence of God,” and she aims to transfer that same experience to other people.34 According to the Art of Flocking curriculum, Taylor is also an abstract painter who uses color as “subliminal communication” to soothe the observer’s spirit, as seen in Out of the Shadows (fig. 3).35 Stewart’s Ancient Spirits (fig. 4) is a kinetic mobile, and when activated by wind, the varied objects and sounds create an intimate and spiritual environment in which the viewer may act.36

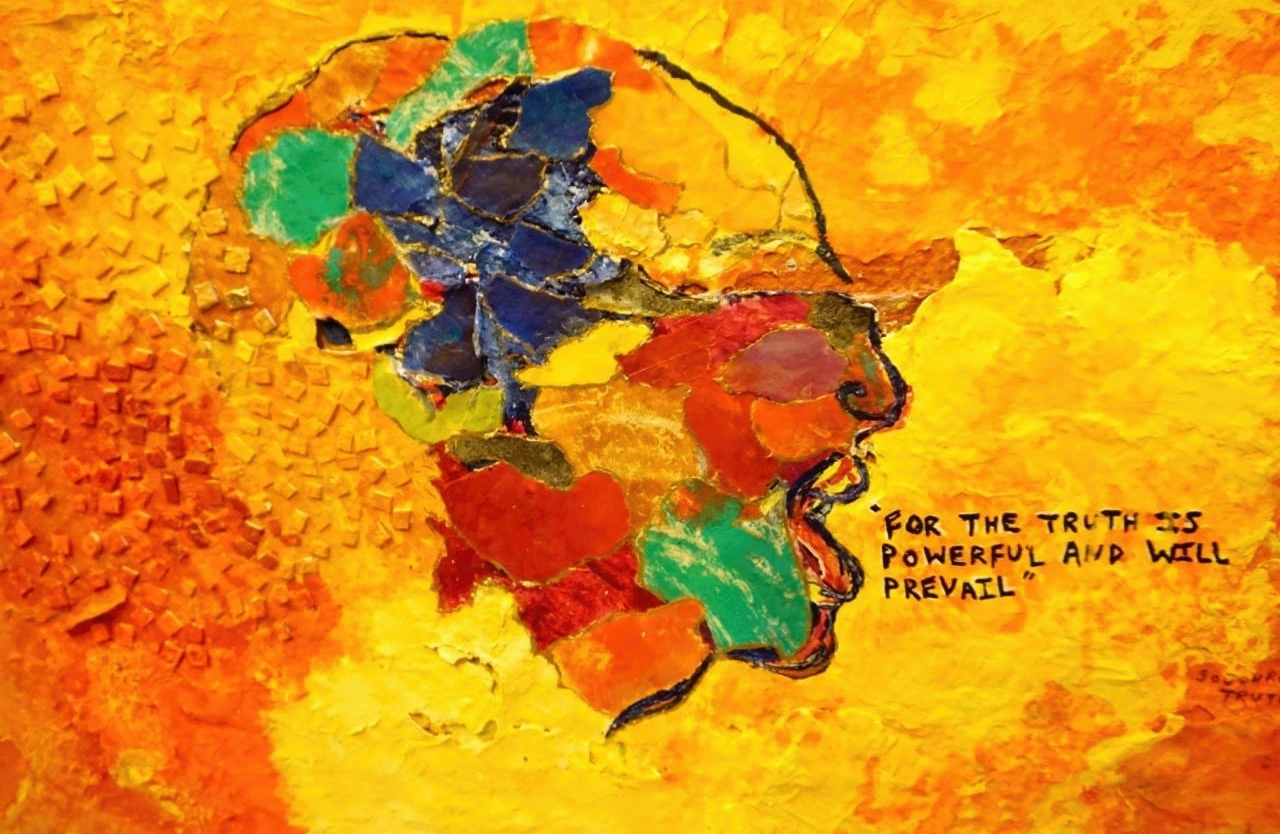

Sapphire and Crystals’ members also create empowering images of African American culture and the African diaspora. A documentarian and fine arts photographer, Blouin captures a global representation of Black culture, whether taking photographs in Chicago, Havana, Hawaii, or South Africa.37 An example is Girl from Blouin’s Havana series (fig. 5). Owens’s painting Revealed Truths and Myths #7 (fig. 6) adds Black faces to Italian Renaissance portraits and asks viewers to move beyond Eurocentric histories of painting to embrace difference by seeing “through our shared, common historical bond of slavery.”38 Williams Jefferson’s Speak The Truth #4: Sojourner (fig. 7) offers an expressionist portrait of the abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth speaking her famous words, “For the truth is powerful and will prevail” from her Book of Life.39

Turner-Crawford, Sylvain, and Hawkins forge ties with Chicago’s Black Arts Movement. Turner-Crawford and Sylvain were especially influenced by AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), a movement founded on the South Side in 1968 “to assert their shared African heritage, aesthetics, and experience of oppression.”40 Turner-Crawford’s vibrant mixed-media collage Meditations on Race and Women (fig. 8) centers the African continent surrounded by images of African women of different ages and an ankh, the ancient Egyptian symbol of life, to engage historical memory, celebration, and empowerment. A muralist, Sylvain painted Color Me South Side (fig. 9) on the wall of Mariano’s grocery store in Bronzeville as a dynamic homage to Black musicians, AfriCOBRA, and the patterns of the African diaspora.41 Hawkins is the daughter of Florence Hawkins, a contributor to the mural The Wall of Respect, which was installed at Forty-Third Street and Langley on the South Side of Chicago in 1967. Conceived of and coordinated by the Visual Arts Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), the mural honored Black heroes such as Nat Turner, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Aretha Franklin.42 Hawkins’ Janice Pot (fig. 10) is, as she states, a “playful take on the two-headed forms found across Mende, Bamana, and other tribal carvings, symbolizing beginnings and transition,” especially for women. Hawkins adds that this work also acknowledges the important influence of Jolly’s hand-built clay figures on her art, for instance Spirit Woman (fig. 11).43

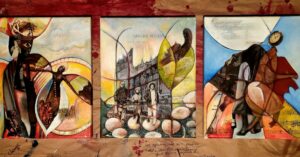

The recent work of Wheatley, Kedem-DuBose, and Hunter responds to issues currently impacting Black communities. Wheatley’s installation Energy grid for grounding into one’s intuition and authentic self. Quells catastrophizing and perpetual fight-or-flight response. Soothes downward spiraling into self-doubt magnified by isolation. May induce fleeting glimpses into the eternal now. Activate re-calibrating energies by gazing into crystals and vessels. Must be 100% voluntary (fig. 12), which was created for an exhibition inspired by Richard Wright’s 1958 novel The Long Dream, provides shamanic tools for healing from the effects of a global pandemic and racial inequity.44 Kedem-DuBose’s mixed-media triptych Covid Series: Tangled Mast History, Tangled Endeavors, Tangled Tango (fig. 13), which she started after the killing of Breonna Taylor, combines Black figures, scores from European sonatas, and other collaged elements to address how the long history of enslavement and segregation is embedded in the United States’ current political moment.45 The work 21st Century Pieta (Requiem for George Floyd) (fig. 14), from Hunter’s Brown Limbed Girls series, uses the image of a mother wearing an “All Power to the People” button and holding her dying son to commemorate the last moments of George Floyd’s life and to allow space for mourning, while also reminding viewers of Black Lives Matter’s continuing demands for accountability and ending police violence.46

Sapphire and Crystals’ Exhibitions: Establishing a Historical Legacy for Black Women Artists

Sapphire and Crystals’ members find common ground for their exhibitions by selecting themes that everyone can embrace and that will prompt dialogue with their audiences regarding the legacies of Black women artists, the Black Arts Movement, and contemporary politics.47 The show Divining Sapphire & Crystals, for instance, curated by Jolly in 1992, explored the meaning of their chosen name.48 The Way My Mama Did (1994) reflected on the “Mama Spirit,” which Jolly defines as reaching “for the artists who went before, the ones yet to be born, and the artists who walk among us now and call themselves black and female.”49 At the suggestion of Richard Mayhew, an original member of the short-lived New York–based Black artists’ collective called Spiral, Owens curated Sapphire and Crystals: In Black and White in 2004 as a homage to the first exhibition staged by Spiral in 1965.50 After the election of President Barack Obama, the group presented Sapphire and Crystals: Beyond Race and Gender, examining how questions around these topics were changing in the United States after 2008.51 Sapphire and Crystals returned to SSCAC in 2010 for Friendships, in 2013 for the exhibition Remember honoring Jolly as their cofounder, and in 2018 for Looking Forward with Love: Lessons Learned from Our Past.52 The catalogues, pamphlets, and press releases published to accompany these exhibitions, which can be disseminated widely and used to further promote the artists’ individual careers, are essential for members to establish a history of their art beyond the actual exhibitions.53

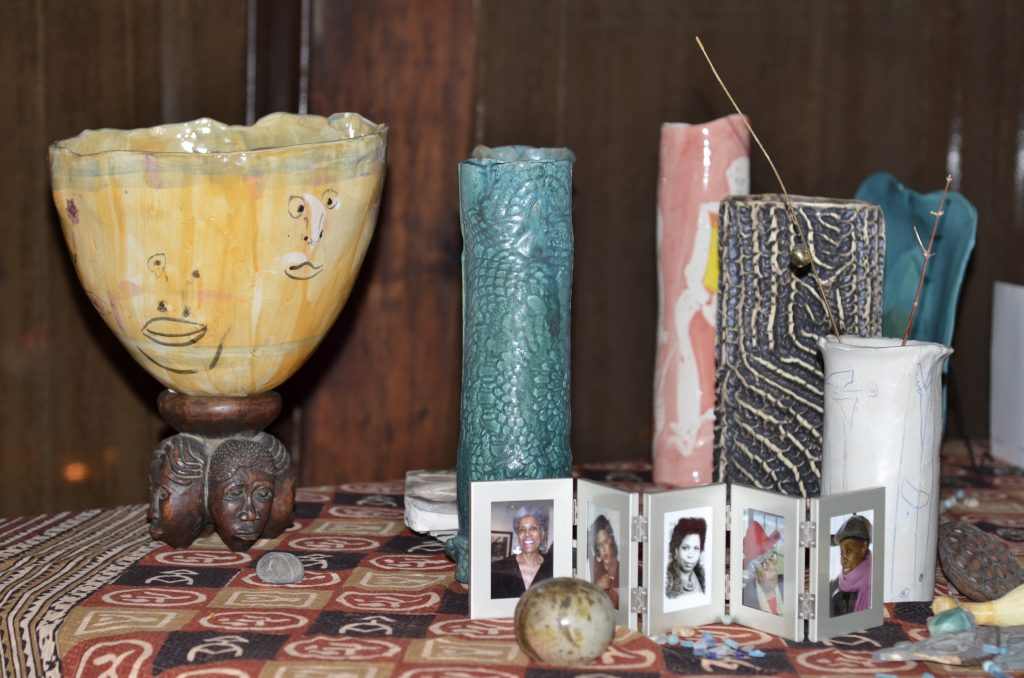

Referenced briefly in the Art of Flocking curriculum, another means to communicate and affirm the histories of the artists of Sapphire and Crystals is by honoring deceased members and elders with altar installations in their exhibitions. Grant Preston explains that she and Jolly both placed altars in their studios for daily meditation, and Jolly suggested that the tradition be extended to the group’s public exhibitions after the passing of members Venus Blue and Renee Townsend in 1997.54 For each altar, members display works they own by the deceased artist alongside a photograph and set them against draped fabric. The installations also include candles, vessels, and other related ephemera, as often found in altars of the Yoruba.55 In addition to honoring Blue’s and Townsend’s memory and transition, Blouin stresses that the altars are intended to establish a sacred space for their art that reflects and enhances the spirituality of their work.56 In December 2009, the collective installed an altar for original member Anna M. Tyler, who died that November. In fall 2010, the group created a Day of the Dead ofrenda (altar) dedicated to Burroughs at the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) after she passed away that year.57 Honoring Burroughs at the NMMA highlights the artist’s strong connections to Mexican art through her fellow artist and friend Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012) and her studies at the Taller de Gráfica Popular workshop in 1952. The ofrenda also reveals the appeal of this tradition to Sapphire and Crystals more broadly.58 There is a long history of Chicana artists, for example, who create ofrendas not just to honor family or loved ones but also to preserve “herstories” often ignored in patriarchal narratives.59 For Sapphire and Crystals’ twenty-fifth anniversary in 2012, a group altar was installed to all those individuals who were lost since 1987, and the 2013 Remember show dedicated to Jolly as cofounder of the group featured an altar with her well-known story pots (figs. 15 and 16). A parallel also can be drawn from the group’s altars to the Black tradition of photographic altars in the home, which bell hooks argues “provided a necessary narrative, a way for us to enter history without words . . . there to sustain and affirm memory.”60

By staging exhibitions at varied locations, members of Sapphire and Crystals can engage with and educate a diverse range of audiences. Exhibitions at SSCAC provide a direct connection between members, their predecessors, mentors in the Black Arts Movement, and the historically Black community of Bronzeville. Shows at Chicago-based women artists’ collectives, such as ARC, Artemisia, and Woman Made, bring the artworks and philosophy of Sapphire and Crystals’ members to primarily white audiences, who are not always familiar with their history. Commercial galleries, such as Nicole Gallery, one of the oldest spaces devoted to African American, African, and Haitian art in Chicago, promotes members’ works to key collectors of art by Black artists. Since many members of Sapphire and Crystals are art educators, exhibiting at area colleges and universities is very appealing because it situates their art in dialogue with larger questions of art history and additional opportunities to interact directly with students.61

Carrying It Forward: Cultivating Community

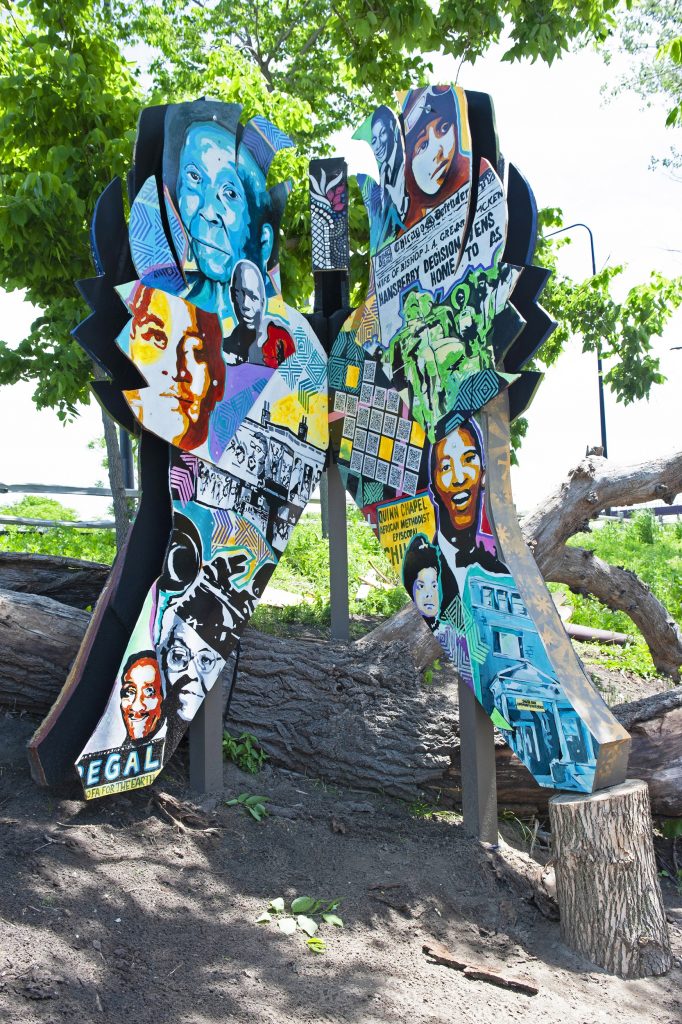

Like their mentor Burroughs, members of Sapphire and Crystals are experienced educators as well as artists, who are committed to bringing art directly to Black communities, especially children. Most members have taught in Chicago’s public schools, alternative arts spaces, museums, and local colleges and universities, as well as the Chicago Park District. Sylvain explains that Black History was not taught in schools and emphasizes that “it was through the arts that we learned so much about our history, about our culture, about ideas of self-esteem and self-expression.”62 Turner-Crawford adds that it is important to provide access to art and these histories since Black children are one day going to be the elders to carry it forward.63 Together these women collaborated with Raymond A. Thomas on the public sculpture Sankofa for the Earth (figs. 17 and 18), installed in the Burnham Wildlife Corridor in historic Bronzeville in association with SSCAC.64 This mixed-media work inspired Hawkins to frame the Art of Flocking curriculum around the work of Sapphire and Crystals.65 Composed of paintings, mosaics, and wooden sculpture, it depicts the Sankofa symbol of a stylized bird with its head turned backward and its feet facing forward. Based on the West African Akan proverb “It is not taboo to go back and fetch what you want,” the work tells us that by understanding our past, we can move forward in our future.66 Following the Wall of Respect, it also honors Black heroes. One side of the sculpture is covered with images of significant figures from Bronzeville’s history, such as Burroughs, poet Gwendolyn Brooks, singer Nat King Cole, aviator Bessie Coleman, and abolitionist, journalist, and educator Ida B. Wells, as well as depictions of the Wall of Respect and the façade of the SSCAC. Thomas added embedded QR codes for each depicted historic figure so the public can learn more, take ownership of this Black history, and share it with others.67 This feature links Sankofa to the young children who gave tours of the Wall of Respect, such as Hawkins’s own brother, by giving agency to the community to tell its own stories.68 Sylvain and Turner-Crawford also emphasize the intergenerational collaboration that brought this work into existence. Children of all ages helped affix the mosaic tiles to the sculpture, which was installed on the third floor of the SSCAC ballroom, and area artists also dropped in to assist at different stages of the work’s creation.69

This brief account of the Art of Flocking program, Sapphire and Crystals’ history, and the collective’s community-based projects demonstrates that there remains a significant need for alternative art and educational opportunities for Black women artists and youth. As Grant Preston observed in 2018, Black women artists continue to lag behind when it comes to gallery representation and inclusion in museum collections and public spaces.70 Sapphire and Crystals has established a powerful new ecosystem in the art world of Chicago to counter the erasure of Black women and to create what brown describes as a “tipping point,” where Black women artists are not just finding greater professional success and visibility but also establishing an infrastructure for future generations to thrive.71

November 22, 2021: An earlier version of this article provided a different link for the curriculum cited in n. 2.

Cite this article: Joanna Gardner-Huggett, “The Art of Flocking: Sapphire and Crystals, Education, Community Building, and Collaboration,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12495.

PDF: Gardner-Huggett, The Art of Flocking

Notes

- adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (Chico: AK Press, 2017), 13. ↵

- Maria Ambriz, Adam Bailey, Elaine Hsu, Juarez Hawkins, and Abena Motaboli, with support of Senior Program Specialist Irina Zadov, “The Art of Flocking, Curriculum,” (Chicago: Chicago Park District, Terra Foundation, and Driehaus Foundation, 2018), https://tinyurl.com/theartofflockingcurriculum. ↵

- brown, Emergent Strategy, 7, 13. ↵

- Ambriz et al., “Art of Flocking, Curriculum.” ↵

- Ambriz et al., “Art of Flocking, Curriculum.” ↵

- Jacqueline Gonzalez Richter, dir., “The Art of Flocking: Cultural Stewardship in the Parks,” documentary filmed 2018, video, 20:31, https://youtu.be/LfOyG8ZEfJ4. ↵

- Richter, “Art of Flocking.” ↵

- Ambriz et al., “Art of Flocking, Curriculum.” ↵

- Richter, “Art of Flocking.” ↵

- See Mary Ann Cain, South Side Venus: The Legacy of Margaret Burroughs (Chicago: Northwestern Universtiy Press, 2018). ↵

- Arlene Turner-Crawford, interviewed by Rebecca Zorach, Never the Same: Conversations About Art Transforming Politics & Community in Chicago and Beyond, June 2012, https://never-the-same.org/interviews/arlene-turner-crawford. ↵

- brown, Emergent Strategy, 36. ↵

- Marva Lee Pitchford Jolly, “Curator’s Statement,” in The Way My Mama Did, Sapphire & Crystals 1994, exh. cat. (Chicago: SSCAC, 1994), 1. ↵

- For more on the history of the Mudpeoples Studio, see Shulie Eshel, dir., Mudpeoples: A Portrait of Clay Artist Marva Jolly (Chicago: Shulie Eshel Productions, 1994), DVD. ↵

- This first exhibition was sponsored by The Arts and Letters Committee of Chicago, alumnae chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., and Mudpeoples Women Artists Resource Sharing Workshop. Tempestt Hazel, “The Vessels That Marva Made: An Interview with Members of Sapphire & Crystals,” Sixty Inches from the Center, December 18, 2018, https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/the-vessels-that-marva-made-an-interview-with-members-of-sapphire-crystals. ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- “League of Black Women,” letter, SSCAC Archives, III, 20, Folder “1974.” Quoted in Rebecca Zorach, “Elective Affinities on the South Side of Chicago,” in The Time is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960–1980, ed. Rebecca Zorach and Marissa H. Baker (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, 2018), 143. ↵

- Zorach, “Elective Affinities,” 143; “Where to Guide: Arts, Exhibits,” Chicago Defender, October 5, 1974, A16. ↵

- Yaoundé Olu, interviewed by Rebecca Zorach, Never the Same, August 2013, https://never-the-same.org/interviews/yaounde-olu. Precedents outside of Chicago include Betye Saar’s exhibition Sapphire, You’ve Come a Long Way Baby held at Suzanne Jackson’s Gallery 32 in Los Angeles in 1970 and the Black women artists’ collective Where We At founded in 1971 by Kay Brown, Dindga McCannon, Faith Ringgold, Carol Blank, and Pat Davis, which continued its work for more than twenty years. See Carolyn Peter and Damon Willick, “GALLERY 32 and Los Angeles’s African American Arts Community,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 30 (Spring 2012): 24; and Kay Brown, “The Emergence of Black Women Artists: The Founding of Where We At,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 29 (Fall 2011): 120, 127. ↵

- Rose Blouin, “A History of Sapphire & Crystals,” unpublished exhibition proposal, 2019. ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” Members did not cite Saar’s exhibition Sapphire, You’ve Come a Long Way Baby as a precedent for naming the group. ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Emma Amos, “Some Do’s and Don’ts for Black Women Artists,” Heresies 15 (1982): 17. ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- brown, Emergent Strategy, 11. ↵

- Richter, “Art of Flocking.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals, including Rose Blouin, Felicia Grant Preston, Juarez Hawkins, Renee Williams Jefferson, Dorian Sylvain, Arlene Turner-Crawford, and Irina Zadov of the Chicago Park District, interview by the author, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Ambriz et al., “Art of Flocking, Curriculum.” See also Pearlie Taylor to the author, July 28, 2021. ↵

- Patricia J. Stewart to the author, July 15, 2021; Patricia J. Stewart, “Sculpture,” https://www.wetpaintbrush.com/collections/sculpture/products/spirits-among-us. ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals, interview. ↵

- “Joyce Owens,” Woman Made Gallery, https://womanmade.org/artwork/joyce-owens-11. ↵

- Sojourner Truth, Book of Life (Battle Creek, MI, 1878), https://www.loc.gov/item/29025244. ↵

- Marissa H. Baker, “AfriCOBRA,” in The Time is Now!, 150–51. For a discussion of AfriCOBRA’s aesthetics, see Barbara Jones-Hogu, “Inaugurating AfriCOBRA: History, Philosophy, and Aesthetics,” Nka, Journal of Contemporary African Art 30 (Spring 2012): 91–95. ↵

- Dorian Sylvain, “Muralist, Educator, Curator & Public Arts Organizer,” https://doriansylvain.com/about-me. ↵

- The Wall of Respect featured more than fifty Black heroes who were statesmen, dancers, rhythm and blues artists, athletes, religious figures, literary icons, and jazz and theater artists. See Abdul Alkalimat, Romi Crawford, and Rebecca Zorach, eds. The Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2017), 49–50. ↵

- Juarez Hawkins to the author, June 23, 2021. ↵

- Rhonda Wheatley, “Artist Statement,” https://www.rhondawheatley.com/artist-statement; the exhibition The Long Dream was held at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art from November 7, 2020, to May 2, 2021, https://mcachicago.org/Exhibitions/2020/The-Long-Dream. ↵

- Makeba Kedem-DuBose, correspondence with the author, August 25, 2021. See also Ana Croegaert, interview with Makeba Kedem-DuBose, December 16, 2020. ↵

- Candace Hunter, conversation with the author, July 23, 2021. ↵

- Arlene Turner-Crawford, interview in Never the Same. See also the Sapphire and Crystals artist file for exhibition pamphlets and catalogues as well as other ephemera, Chicago Artist Files, Harold Washington Library, Chicago. ↵

- Divining Sapphire & Crystals: An Exhibition of Contemporary Art by African American Women Artists, exh. cat. (Chicago: Mudpeoples Studio, 1992). ↵

- Jolly, in The Way My Mama Did, 1. ↵

- Joyce Owens to the author, July 7. 2021. For more on the history of Spiral, see Courtney J. Martin, “From the Center: The Spiral Group, 1963–1966,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 29 (Fall 2011): 87–98. ↵

- Joyce Owens curated Sapphire & Crystals: Beyond Race and Gender at the Noyes Cultural Center in Evanston:, 2009; see also the exhibit pamphlet. ↵

- Joyce Owens to the author, July 13, 2021. ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” ↵

- Turner-Crawford added that the altars featured in Betye Saar’s exhibition held at Artemisia Gallery in 1984 may have also influenced this Sapphire and Crystals tradition; members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Robert Farris Thompson, “Face of the Gods: The Artists and Their Altars,” African Arts (Winter 1995): 50–53. ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Joyce Owens, “Curator, ‘State of G/RACE’ exhibition in Chcago {sic} at Woman Made Gallery,” December 26, 2012, https://www.artmajeur.com/fr/joyceowens/news/628370/curator-state-of-g-race-exhibition-in-chcago-at-woman-made-gallery. ↵

- Cain, South Side Venus, 104–6. ↵

- Laura E. Pérez, “Altar, Alter,” in Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 91–94. ↵

- bell hooks, “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: New Press, 1995), 62. ↵

- To date, Sapphire and Crystals has exhibited at the following colleges and university: Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, IL (1993); Concordia University, River Forest, IL (2004); Elmhurst College, Elmhurst, IL (2010); and Prairie State College, Chicago Heights, IL (2013). See Sapphire and Crystals, events binder, Where the Future Came From exhibition, Glass Curtain Gallery, Columbia College Chicago, Chicago, 2018, and Blouin, “History of Sapphire & Crystals.” ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- For a brief history and chronology of the SSCAC, see https://www.sscartcenter.org/about-us. ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Ambriz et al., “Art of Flocking, Curriculum.” ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Juarez Hawkins, “Child of the Wall,” presented at the conference “Art, Publics, Politics: Legacies of the Wall of Respect,” Block Museum, 2017, https://soundcloud.com/user-251454390/legacies-juarez-hawkins. ↵

- Members of Sapphire and Crystals interview, June 9, 2021. ↵

- Hazel, “Vessels That Marva Made.” See, for example, the study by Chad M.Topaz, Bernhard Klingenberg, Daniel Turek, Brianna Heggeseth, Pamela E. Harris, Julie C. Blackwood, C. Ondine Chavoya, Steven Nelson, and Kevin M. Murphy, Diversity of Artists in Major U.S. Museums, February 11, 2019, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1812.03899.pdf. ↵

- brown, Emergent Strategy, 16. ↵

About the Author(s): Joanna Gardner-Huggett is Associate Professor of History of Art and Architecture at DePaul College of Liberal Arts and Sciences