“The Art of Living”: Selma Burke’s Progressive Art Pedagogies from the New Deal to the Black Arts Movement

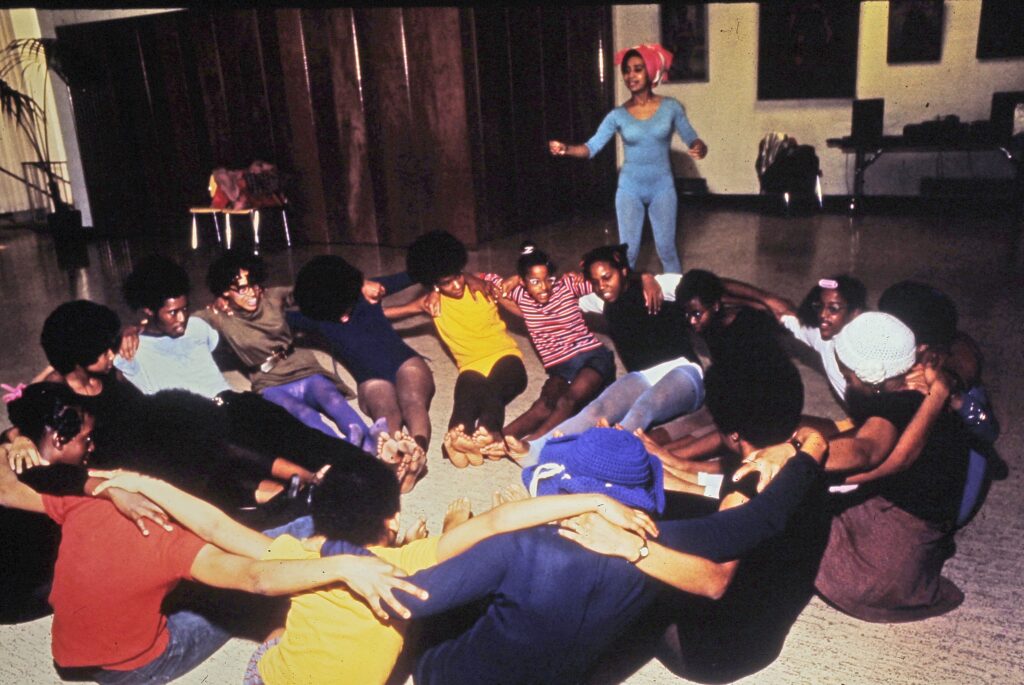

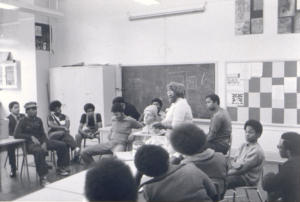

In August 1967, prominent African American sculptor Selma Burke (1900–1995) accepted a position as a consultant to develop a Black-serving, youth-oriented community art center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Sponsored by the Carnegie Institute (CI) and the A. W. Mellon Trust (MT), the Selma Burke Art Center (SBAC), as it came to be known, operated from 1971 to 1982 in Pittsburgh’s East Liberty neighborhood. Local artist-educators offered classes in dance, drawing, sculpture, painting, weaving, and television production, among other topics (figs. 1–4). In her acceptance letter to Theodore Hazlett, the president of the MT, Burke acknowledged her approach might “stretch” his “conception of art.”1 She expressed her hope that Hazlett would “also want this workshop and cultural center to include and foster the art of living.”2 The phrase “the art of living” was derived from the educational philosophy of John Dewey and harkened back to the progressive educational movements popular when Burke came of age in the 1920s and 1930s.3 As this essay will show, Burke’s belief in the core Deweyan principle of the importance of experiential education to improve the everyday lives of people from all classes informed her work at the SBAC and defined her artistic pedagogy and career.

Like other successful Black artists of her generation, Burke fought to study in European ateliers and elite institutions in New York (fig. 5), moved in interracial avant-garde and communist circles, and worked for the Federal Art Project (FAP), a branch of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).4 At the WPA-sponsored Harlem Community Art Center (HCAC), initially run by sculptor Augusta Savage, Burke taught classes alongside Charles Alston, Elton Fax, and Norman Lewis (fig. 6).5 These artist-educators worked in New Deal art-education programs in which Dewey’s democratic and progressive ideals held sway.6 Dewey critiqued the effects of capitalism on democratic culture and believed that the separation of art from the lives of most people—or what he called “the museum conception of art”—was detrimental to society.7 Because, as he said, art contained the “the clarified and intensified development of traits that belong to every normally complete experience,” Dewey believed experiential art education was a uniquely effective avenue to improve the experience of everyday life.8 In turn, a society that cultivates the skills of aesthetic experience and sensitivity would produce a more engaged, creative, and adaptable public, thus improving the conditions of democracy.9 According to Holger Cahill, the director of the FAP, community art centers advanced Dewey’s call for the democratization of art because they provided a hands-on artistic education to the public within their own communities.10

This essay traces how, over the course of six decades, Burke developed a practical, hands-on, and technical arts education to enhance the lives of her students, maintaining her Deweyan pedagogy even as its popularity waned. First it establishes how Burke incorporated these pedagogical views into her deep faith in universal aesthetics, belief in the autonomy of art, and unwavering investment in racially integrated classrooms as the best way to educate Black youth. I argue that Burke translated her Deweyan aesthetic and pedagogical convictions into her research and explore how these ideals were received by the Black press when implemented at her private school of sculpture during the 1940s. I show how Burke continued to advocate for the availability of a technique-based arts education for people of all classes, even after the dissolution of the WPA, when progressive ideals fell out of favor. Finally, the essay explores the tensions that arose when Burke enacted her pedagogical principles at the SBAC and came into conflict with both the proponents of the Black Arts Movement (BAM), who favored Afrocentric aesthetics and Black nationalism, and the white philanthropists who funded the center.

Burke’s career mirrors that of other Black artist-educators of her generation in the United States who sought equal treatment within an imperfectly integrated art world. Yet, Burke stands out for her commitment to community-based youth art education. Notably, Burke never taught courses at the university level, as did many of her peers, instead working in community centers or elementary and secondary schools.11 Whereas the growing literature on midcentury US Black artists has focused on those who pursued university-level teaching jobs after the WPA,12 this essay takes a broader look at the reach and legacies of US progressive art pedagogies in the United States to shed new light on the ongoing debates about the role of Black art in society and the obligations of the artist to the community.13 In order to expand this narrative, I mine archival sources to uncover the rich aesthetic and pedagogical thinking of Burke and other artist-educators, revealing the significance of teaching to US Black artists at the time. I consider the place of art education within a number of key debates, including the autonomy of art versus the obligations of Black artists to the community; the promotion of a universal aesthetic standard based in technical proficiency versus Afrocentric aesthetics meant to stimulate Black pride; and Black nationalist, segregated education versus integrated educational settings. By following the development of Burke’s pedagogy from the 1930s through the 1980s, this essay demonstrates the important role progressive education continued to play for Black artist-educators after the WPA and reveals how pedagogy was a central strategy and battleground for significant debates about Black art.

Burke’s Deweyan Terms

Throughout her life, Burke wrote extensively about her entwined aesthetic and pedagogical philosophies in Deweyan terms. She repeatedly mythologized her past, saying that her childhood curiosity and interaction with the red-clay soil of North Carolina drew her to art making.14 In these anecdotes, she emphasized that it was her personal experience of clay that signaled her path as an artist, as Carol Hanner’s 1981 newspaper article “Art Beckoned From the Mud: Selma Burke Heeded the Call” suggests.15 This arc echoes Dewey’s belief that routine individual experiences and sensations give rise to aesthetic feelings and sensitivities, which can be refined through hands-on training.16 Burke’s curiosity about materials inspired her to seek professional training in the techniques of art making, which, because of her race and gender, she had to fight to receive in Europe and New York. Informed by her own difficulty in acquiring training, Burke maintained a lifelong commitment to expanding access to a rigorous art education regardless of class, race, or geographic location.

This commitment to access and inclusion is evident in her 1940 application to the Julius Rosenwald Foundation, in which she sought a grant to conduct a geological survey of the South and identify domestic sources for heavy stone suitable for direct carving.17 Because these materials were usually imported from Europe, many students lacked access to the stone necessary to practice direct-carving methods and reach their potential as sculptors. As she touted in her application, Burke endeavored to make stone carving more accessible to students by making stone cheaper, thus democratizing elite art education, bringing art into the everyday lives of people, and undermining “the museum conception of art.” American art as a national project would improve through expanded access to artistic materials, which would subsequently improve the quality of its art education. This claim aligned Burke’s proposal with nationalist agendas in which “American art” was viewed as a project to be advanced on an international stage.18 In her discussion of Black artists who applied for Rosenwald grants, the art historian Lindsay Twa points out that application rhetoric should be considered as evidence of strategy rather than as a direct translation of an artist’s personal beliefs.19 It seems likely that Burke’s use of nationalist rhetoric in her application was designed to appeal to the funders, as that was not a view echoed elsewhere in her writing. However, Burke’s belief that research should inform technical, hands-on instruction and that this type of education could help achieve democratic goals was likely sincere, given her career-long advocacy for art education as a tool for social progress.

Burke’s stated goals for the project (making the stone more accessible and training students in direct-carving techniques) illustrate how her artmaking goals and teaching intertwined. In her application, Burke made clear that her research would be “accessible to students and teachers of sculpture.”20 She concluded, “I plan only to try to improve my work as a sculptor and to give to students the benefits of what I have learned.”21 The mutual advancement of goals through individual practice and education was already evident in Burke’s own hard-won but elite art training and her time spent teaching at the HCAC in the late 1930s. Her academic education in Parisian ateliers and then at Columbia University emphasized classical techniques.22 She learned to render form and volume in three dimensions and used drawing to develop a sense of line that could be transferred to carving.23 In turn, Burke taught students these skills during her time at the HCAC, thus bringing high academic standards and practices to the youth of Harlem (see figs. 5 and 6).24

The HCAC was the most famous of the New Deal–era community art schools, and it made a profound impact on the course of American art.25 It provided fertile ground for the training of many prominent Black artists, including Jacob Lawrence and Roy DeCarava, and provided much-needed employment and income for many more.26 Despite the impact of Savage and the HCAC, it is important not to overstate their operational influence. Following the art historian Mary Ann Calo, who cautions scholars against overestimating the influence of HCAC and official New Deal policies at the cost of recognizing localized differences,27 I frame Burke’s connection to the HCAC to highlight two significant pedagogical continuities: first, her belief that an ideal art education should be racially integrated and accessible to Black youth of all classes, and second, that hands-on, skills-based instruction with proper materials, including sculpting with clay and stone, should be available to people of all races and classes. Both of these goals were part of her progressive educational agenda and provided the motivating force behind her 1940 Rosenwald application and later endeavors.

Burke’s correspondences and the archival record of her visits and interactions with other artist-educators indicate her ongoing connection to a cohort at HCAC and the ways in which the group’s pedagogical ideals aligned. For instance, in 1969, Elton Fax, an artist-educator from the HCAC who worked in a community art center in Queens, wrote to Burke that “there was no reason for our talented youth to languish in an atmosphere of neglect as we did for so long.”28 In this letter, Fax gestures to the racial prejudice they each faced during their early careers and to their current ability to aid talented Black youth by working in community centers. For Burke, the remedy to the institutional neglect she had to overcome in order to attain artistic training was to offer a technical education to everyone. Providing access to shared artistic spaces would serve as both racial uplift and an expansion of democracy. Though influenced by Dewey’s philosophy throughout her career as an artist-educator, Burke’s emphasis on the value of sculptural materials and her experience as a woman of color who benefited from a European technical education also shaped her artistic pedagogy.

Universal Standards in the Integrated Classroom

As New Deal programs petered out and wartime scarcity in public arts funding set in during the 1940s, Burke continued to develop her sculptural practice and foster her commitment to providing students with an integrated, internationally informed, technical art education. Using a cache of supplies left to her by the Russian-French sculptor Ossip Zadkine, she founded the Selma Burke School of Sculpture in January 1946, an integrated sculpture school for adults in Greenwich Village.29 Remarkable images of her school reveal a student body diverse in race, age, and gender (fig. 7). In the press, Burke commented that the school’s location outside Harlem, in what she called “the Left Bank” of the United States, served as an intentional refutation of the geographic and cultural segregation of Black artists.30 Some coverage emphasized the interracial dimension of the school, suggesting that it was an astute political strategy. For instance, a 1947 Ebony article notes that two-thirds of the enrollment was white, evidence of the “soundness of her philosophy” that art can be “a great leveler of class and race.”31 Thus, in the late 1940s, Burke’s preference for integrated art education was still understood as progressive and democratic, not as an erasure of Black culture or a denial of Black pride, as it would come to be seen in the 1970s with the rise of BAM.

BAM was part of a wave of cultural production associated with the Black Power movements that began in reaction to the assassination of civil rights leaders and in association with international calls for decolonization.32 By the late 1960s, BAM artists and thinkers based in the United States, such as Larry Neal, Amiri Baraka, Ron Karenga, and Jeff Donaldson, argued that Black artists and their art must serve the greater goal of Black liberation.33 These artists rejected core modernist tenets, including the autonomy of art and the privileging of individual expression, and embraced political form and content, including public murals and Afrocentric subjects.34 As the American studies scholar Margo Natalie Crawford notes, this commitment to politics ran alongside experiments with abstraction and other visual techniques that emphasized African heritage.35 Throughout this era, BAM artist-educators published critiques of “universal” aesthetics, which concealed white hegemony, and instead promoted Black-specific aesthetics rooted in African traditions.36

Though Burke discredited racist hierarchies within art, she did not reject universal aesthetic standards inherited from European aesthetics. Burke argued that if art made by Black people displayed aesthetic greatness, it was of universal value to all people, regardless of race.37 The inherent value of traditional African sculptures, for Burke, was found in the masterful use of materials, shape, line, and volume, not in the ostensibly Black hands that made them or the undeniably Black spirit they conveyed, as those associated with BAM believed.38 Burke’s universal reading of African art contrasted with the aesthetics of BAM, which extolled the genealogical basis of African cultural heritage and promoted a set of specifically Black aesthetic standards.

Rather than claiming, as BAM did, that Black art and, by extension, art education should only be in the service of Black liberation, Burke believed integrated art education would remove barriers that prevented Black artists from adequately developing as artists and people. Though focused on the success of individual students rather than collective liberation, Burke’s commitment to integrated art education was founded in her belief that a nonsegregated classroom provided a better environment for Black youth than a racially divided one.39 A 1948 profile of Burke in Ebony discusses her commitment to “bringing art to Negro boys and girls so there can be more appreciation for living.”40 As Burke said, “Art is the basis for everything.”

The press coverage of the late 1940s emphasizes Burke’s commitment to providing an integrated, technique-focused art education to Black youth and reveals her belief that Black artists should employ universal aesthetic standards that reinforce the autonomy of art. By the late 1960s, however, these views would be out of step with the radical Black movements that emerged after the assassinations of Malcolm X and other Black leaders and that agitated for varying degrees of separatism and Black cultural nationalism.

Progressive Pedagogy and the Black Arts Movement in Pittsburgh

The SBAC opened to skepticism within the Black arts community because of its connection to Pittsburgh’s Urban Renewal Authority (URA), the Mellon Trust, and the long-exclusionary Carnegie Institute, each of which were powerful, white-controlled institutions in Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape.41 In many cities, including Pittsburgh, private corporations ran urban renewal schemes with federal money. Armed with the power of eminent domain, they leveled Black communities with little input from or regard for residents. As I have argued elsewhere, the Mellon family and their organizations were the principal designers of the urban renewal plan that resulted in the displacement of eight thousand primarily Black residents from Pittsburgh’s Hill District between 1955 and 1965.42 In fact, the uprisings in the Hill District that followed this displacement led Hazlett to invite Burke to develop a Black arts program.43 It is significant that Hazlett sought out a Black artist with a national profile to lead this initiative rather than hiring a local Black artist already embedded in the community. While Burke’s credentials made her a standout candidate, her lack of connection to existing Black arts communities (and lack of involvement in local controversies) in Pittsburgh likely appealed to white philanthropists who saw the project as a way to ease racial tensions in the city.

The Trust provided the SBAC with an annual operating budget of $100,000, which was administered through the Carnegie Institute. Although located in East Liberty, a red-lined Black neighborhood many miles away from the CI, the SBAC was still technically part of the CI. According to letters and reports, the East Liberty location was important to the MT’s vision for the center: it was removed from the museum’s stately building, and it was in a Black neighborhood.44 Hazlett secured a former Mellon Bank building in East Liberty that had been purchased by the URA for revitalization.45 As part of Hazlett’s arrangement, the CI hired Burke as an artist-in-residence and instructor and gave her a studio in the museum, not in the SBAC.46 Moreover, despite her requests for more power at the center that bore her name, Burke never served in any official capacity within the SBAC administration (these roles were held by Black men only until 1977).47 In her capacity as artist-in-residence and instructor for the CI, Burke taught an extraordinary number of sculpture demonstrations in schools, visiting over sixty thousand Pittsburgh public schoolchildren on behalf of the CI during her five years there (fig. 8). The source of her employment and her public role as a CI teacher firmly embedded her within Pittsburgh’s white philanthropic landscape. Even though dedicated to Black uplift, by nature of her institutional position and affiliation, she worked in opposition to BAM’s core belief in Black self-determination.48

SBAC’s development (1967–71) coincides with a period of increased activism, as artists protested the lack of work by Black artists in museum collections and exhibitions (especially in New York) and debated the social role of Black artists.49 The SBAC records show that artist-educators in Pittsburgh were thinking deeply about the complexity of philanthropy and white control at the local and national levels. For instance, in fall 1971, the SBAC convened a series of informal discussions with local stakeholders, the results of which were consolidated into a report. Questions included: “In what ways would the black community appreciate an art center within the community?” and “Should black art represent the political, social, and economic situations of black people?”50 These questions indicate the influence of contemporary debates about the role of BAM at the SBAC.

The views recorded in the report were diverse but fell along familiar divides. Some discussants placed service to the community above all else for Black artists, while others assumed that community was a given rather than a goal and that individual expression was the point of art.51 Some participants referenced the urgency of museum protests and the necessity of showing Black art. Others resisted the idea that “Black art” was a category at all. Nearly all agreed that the center should employ Black artists and that the SBAC needed to work to earn the community’s trust.

Contemporaneous controversies and divisions in Pittsburgh’s Black art scene also impacted the early years of the center. Two months after the SBAC opened, Black artist-educators from across the country convened in Pittsburgh for USA? . . .1971–1972, An Afro American Artist Presentation: A Visual and Literary Experience, an event organized by Burke’s coworker in the CI Education Department, J. Brooks Dendy, and prominent African American artist Benny Andrews.52 Betye Saar, Charles White, Margaret Burroughs, Samella Lewis, Camille Billops, and other Black artists and educators came to Pittsburgh to participate in a series of lectures, dinners, and exhibitions of work by Black artists. To their astonishment and horror, visiting exhibiting artists found the CI had hung their artwork in a disused bomb shelter rather than in a gallery, a move Andrews called a severe “affront” to participating artists.53

Due to an already strained relationship with Dendy, Burke declined to show in the exhibition but hosted her friends and peers for a tour of the SBAC as part of the festivities.54 Although Burke was angered by the planning of the exhibition, the situation provided her with an opportunity to reconnect with other progressive artist-educators from around the country.55 For instance, the episode led to a renewed correspondence between Burke and Burroughs, the director of Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC).56 This contact led Burroughs to invite Burke to exhibit her work at the SSCAC and to give a series of lectures on the role of art education in Black life.57

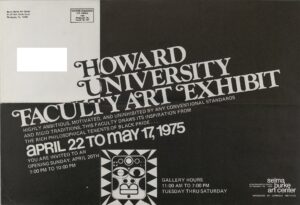

By leveraging her many connections, Burke ensured that the SBAC participated in national and international Black arts networks. Exhibitions and visiting artists exposed the students and faculty to cutting-edge art made by Black artists with diverse ideologies, including overtly political examples of BAM-influenced work. For instance, in 1975, the SBAC mounted a Howard University faculty show that included work by Jeff Donaldson and other members of the prominent Black Arts group AfriCOBRA, focused on Black pride (fig. 9). Importantly, Burke’s aesthetic views, though in opposition to BAM, did not foreclose the kinds of art and politics on view at the SBAC.

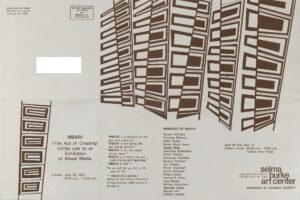

Burke also tried to foster a working environment that was welcoming to divergent views. Many of the SBAC’s teaching staff were interested in Afrocentric aesthetics and held community-oriented philosophies (fig. 10). Thanks to Burke’s multipronged approach to art education, SBAC students could find both Afrocentric self-exploration courses that drew from African diasporic traditions and classes based in classical European traditions where they would gain the skills necessary to expertly manipulate materials. In 1971, more than a third of SBAC instructors were members of Mbari, an Afrocentric Black artist group in Pittsburgh spearheaded by sculptor Thaddeous Mosley.58 BAM artist and SBAC instructor Charlotte Ka (then Charlotte Richardson) provided formal feedback on the center’s shortcomings. During a staff meeting in 1973, she registered concerns that public programs were taking space and resources away from educational programs and offered practical recommendations for improving the SBAC that were garnered from her teaching experience at the Harlem Children’s Carnival.59 Her suggestions included making the SBAC more inviting to and supportive of Black youth, and she offered strategies for amplifying the impact of the center within the community.60 Notably, her pedagogical suggestions did not include reference to technical education or materials but were geared toward ways to cultivate an appealing and accessible environment for the existing Black community.

Records indicate that Ka’s suggestions and those of other women instructors were not taken seriously by SBAC director Walter Sims.61 Another instructor, Dee Levister, voiced concerns about Sims’s lack of professionalism and mistreatment of instructors, and she forcefully critiqued his management of the center in her resignation letter.62 Earlier bids by Burke and other women for more power at the SBAC were largely ignored by the all-male leadership at the SBAC, CI, and MT.63 Despite her request for a more active role in the day-to-day operations of the center, Burke was relegated to the role of a figurehead and board member.

The SBAC gradually became more aligned with BAM and more overtly feminist during the late 1970s.64 It is significant that this shift came after Burke’s retirement in 1976 and with the MT’s sudden divestment from the SBAC in 1978.65 In 1977, Mbari member and longtime SBAC instructor Barbara Peterson functionally took over control of the struggling center and during her tenure ushered in a feminist and Afrocentric agenda that was reflected in the framing of its subsequent exhibitions.66 For instance, the SBAC advertised the exhibition Two Black Women: Marcia Jameson and Eleanor Burnette by citing Jameson’s desire to overcome the “tokenism” that limits Black women artists.67 Another feminist legacy of Burke’s efforts at the SBAC was the formation of Women of Visions, a Pittsburgh collective of Black women artists cofounded by several SBAC instructors, which is still in existence today.68

From its inception in 1971, the SBAC was supported by Black women who were fighting for increased access to the arts to better serve their communities and their own artistic practices. Reviewing the diversity of styles operating at the SBAC suggests the value of community art centers as rich sites for pedagogical and aesthetic growth. Burke harnessed both inclusive pedagogies and respect for artistic autonomy to cultivate Black pride, to instill an appreciation for technique, and to facilitate Black artistic creation—in short, to offer an art education in the service of Black life.

Cite this article: Rebecca Giordano, “‘The Art of Living’: Selma Burke’s Progressive Art Pedagogies from the New Deal to the Black Arts Movement” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12771.

PDF: Giordano, The Art of Living

Notes

- Selma Burke to Theodore Hazlett, August 9, 1967. Selma Hortense Burke Papers, Spelman College Archives (here after SHBP). ↵

- Burke to Hazlett, August 9, 1967. ↵

- For a useful overview of the significant literature on John Dewey, the WPA, and the FAP, see Jillian Russo, “The Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project Reconsidered,” Visual Resources 34, no. 1/2 (March/June 2018): 13–32, https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2018.1436800. On Burke’s formative years, see Lisa E. Farrington, “May Howard Jackson, Beulah Ecton Woodard, and Selma Burke,” in Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Amy Helene Kirschke (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014), 115–56. Burke recounted her early years many times in her life in her writing, interviews, and oral histories. ↵

- Farrington, “May Howard Jackson,” 139. ↵

- For an overview of the HCAC, see Mary Ann Calo, “A Community Art Center for Harlem: The Cultural Politics of ‘Negro Art’ Initiatives in the Early 20th Century,” Prospects 29 (October 2005): 155–83, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0361233300001721. For an assessment of the HCAC’s legacies, see Mary Ann Calo, “Expansion and Redirection: African Americans and the New Deal Federal Art Projects,” Archives of American Art Journal 55, no. 2 (September 2016): 80–91, https://doi.org.pitt.idm.oclc.org/10.1086/689717; and Jeffreen M. Hayes, Augusta Savage, Renaissance Woman (London: GILES, 2018). ↵

- Russo, “Works Progress Administration,” 18. ↵

- John Dewey, Art as Experience (1934, repr. New York: Wideview/Perigree, 1980), 6. ↵

- Dewey, Art as Experience, 48. On the educational significance of the manipulation of physical media due to its requirement of increased perception, see 51–53. Dewey articulates his refined definition of art and aesthetics in Art as Experience, a topic he had been writing about for several decades, including in his role as Director of Education at the Barnes Foundation. Dewey dedicated Art as Experience to Albert C. Barnes. For more on this collaboration and Dewey’s role in the Barnes Foundation, see George Hein, “John Dewey and Albert Barnes,” in Progressive Museum Practice: John Dewey and Democracy (Walnut Creek, Calif: Left Coast Press, 2012), 97–122. ↵

- Dewey writes that “democracy” is “more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience”; see Democracy and Education (1916; repr. Gorham: Myers Education Press, 2018), 48. Political philosopher Axel Honneth situates Dewey’s concept of “democratic ethical life” as an ideal of “social cooperation,” which he understands “as the outcome of the experience that all members of society could have if they related to one another cooperatively” and “as a large-scale experimental process”; see “Democracy as Reflexive Cooperation: John Dewey and the Theory of Democracy Today,” Political Theory 26, no. 6 (December 1998): 763–83, at 780 and 778, respectively. ↵

- Holger Cahill, “American Resources in the Arts,” in Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, ed. Frances V. O’Connor (Greenwich: New York Graphic Society, 1973), 33. ↵

- For instance, Aaron Douglas, Hale Woodruff, Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, Loïs Mailou Jones, Vertis Hayes, and John Biggers taught at HBCUs. ↵

- See the excellent recent work by Sharif Bey, “Aaron Douglas and Hale Woodruff: African American Art Education, Gallery Work, and Expanded Pedagogy,” Studies in Art Education 52, no. 2 (2011): 112–26; Rebecca VanDiver, Designing a New Tradition: Loïs Mailou Jones and the Aesthetics of Blackness (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020); Rebecca VanDiver, “Art Matters: Howard University’s Department of Art from 1921 to 1971,” Callaloo 39, no. 5 (2016): 1199–1218; John Ott, “Hale Woodruff’s Antiprimitivist History of Abstract Art,” Art Bulletin 100, no. 1 (March 2018): 124–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2017.1367913; and Earnestine Jenkins, “Muralist Vertis Hayes and the LeMoyne Federal Art Center: A Legacy of African American Fine Arts in Memphis, Tennessee 1930–1950s,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 73, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 132–59. The following exhibition catalogues and essays also address the role of university pedagogy for Black artists in the United States at midcentury: Ester Adler, “Charles White, Artist and Teacher,” in Charles White: A Retrospective, ed. Sarah Kelly Oehler and Esther Adler (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2018), 141–57; M. Akua McDaniel, “The Visual Education of Spelman Women,” in Bearing Witness: Contemporary Works by African American Women Artists, ed. Jontyle Theresa Robinson (New York: Spelman College and Rizzoli International Publications, 1996); and Amalia K. Amaki and Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, Hale Woodruff, Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, and the Academy (Atlanta: Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 2007). ↵

- For an overview of these debates, see A. B. Spellman, “Introduction to Theory/Criticism,” in SOS/Calling All Black People: A Black Arts Movement Reader, ed. James Edward Smethurst, Sonia Sanchez, and John H. Bracey (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 23–25. ↵

- See Selma Burke, interview with Camille Billops, April 30,1976, transcript, Camille Billops and James V. Hatch Archives at Emory University, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University; Carol Hanner, “Art Beckoned From the Mud: Selma Burke Heeded the Call,” Winston Salem Journal, July 26, 1981, C1, C6. ↵

- Hanner, “Art Beckoned,” C1. ↵

- Dewey, Art as Experience. For a helpful distillation of Dewey’s core concept of experience in terms of Burke’s contemporary Stuart Davis, see also John X. Christ, “Stuart Davis and the Politics of Experience,” American Art 22, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 45–48. ↵

- Selma Burke, Rosenwald 1940 grant application, box 398, folder 13, Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives, Franklin Library, Special Collections, Fisk University. ↵

- Russo, “Works Progress Administration,” 28. For a transatlantic account of the project of American identity forged through art primarily before the WPA, see also Wanda Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). ↵

- Lindsay Twa, “Artists’ Statements at Work: Visual Artists and the Julius Rosenwald Fund,” Forum for Modern Language Studies 48, no. 4 (Fall 2010): 430. ↵

- Burke, Rosenwald 1940 grant application. ↵

- Burke, Rosenwald 1940 grant application. ↵

- Farrington, “May Howard Jackson,” 139–40. ↵

- Farrington, “May Howard Jackson,” 139–40. ↵

- Burke, Rosenwald 1940 grant application. ↵

- Sharif Bey “Augusta Savage: Sacrifice, Social Responsibility, and Early African American Art Education,” Studies in Art Education 58, no. 2 (2017): 125–40; Hayes, Augusta Savage; Calo, “Community Art Center for Harlem.” ↵

- Russo, “Works Progress Administration,” 13. ↵

- Calo, “Expansion and Redirection,” 86. ↵

- Elton Fax to Selma Burke, February 2, 1969, box 1, folder 3; Selma Hortense Burke Papers, Spelman College Archives (hereafter: SHBP). Fax was also offered the position of director at the SBAC in 1969 and declined to continue running an arts center in Queens; see Elton Fax to Theodore Hazlett, July 25, 1969, box 30, folder 9, A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust Records, 1930–1980, AIS.1980.29, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System (hereafter MTR). ↵

- “Poetess in Stone,” May 1946, clipping, box 11, SHBP. ↵

- Unidentified clipping, box 11, SHBP. ↵

- “Selma Burke,” Ebony, March 1947, clipping, box 11, SHBP. ↵

- BAM leader Larry Neal states that “Black art is the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept”; see “The Black Arts Movement,” Drama Review: TDR 12, no. 4 (Summer 1968: 29. ↵

- Neal, “Black Arts Movement,” 30; Ron Karenga, “Black Cultural Nationalism,” Black World / Negro Digest 17, no. 3 (January 1968), repr. in The Black Aesthetic, ed. Addison Gayle Jr (Garden City: Doubleday, 1971), 32–38; Jeff Donaldson, “AfriCobra I (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists): Ten in Search of a Nation,” Black World / Negro Digest 19, no.12 (October 1970): 80–89. ↵

- Spellman, “Introduction to Theory/Criticism,” 23–25. Numerous primary texts on these topics were anthologized at the time, including in Gayle, Black Aesthetic, and Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal, eds., Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing (1968; repr., Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2007), as well as in more recent anthologies, such as Smethurst et al., SOS. ↵

- Margo Natalie Crawford, “When Black Experimentalism Became Black Power: The Black Arts Movement and Its Legacies,” in the Routledge Companion to African American Art History, ed. Eddie Chambers (London: Routledge, 2019), 105. ↵

- See contributions by Tom Lloyd, Jeff Donaldson, Bing Davis, Francis and Val Grey Ward, and Amiri Baraka in Black Art Notes, ed. Tom Lloyd (1971, repr. Brooklyn: Primary Information, 2020). Lloyd produced this compendium of significant BAM texts published in protest of the Whitney Museum’s exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America. ↵

- Selma Burke, quoted in James G. Spady, “Three to the Universe: Selma Burke, Roy DeCarava, Tom Feelings,” in 9 to the Universe, Black Artists (Philadelphia: Black History Museum, 1983), 18. ↵

- Undated manuscript, box 6, SHBP. ↵

- “Selma Burke,” Ebony, box 11, SHBP. ↵

- Rachel E. Diggs, “Sculptress Has Known Hard Knocks,” February 15, 1948, clipping, SHBP. ↵

- Minutes of First Staff meeting, MTR. ↵

- Rebecca Giordano, “An Aluminum Sheen on Urban Renewal” in Metal from Clay: Pittsburgh’s Aluminum Stories, ed. Alex Taylor (Pittsburgh: University Art Gallery, 2019), 68–69. ↵

- Theodore Hazlett to Selma Burke, May 29, 1968, box 30, folder 9, MTR. Though Burke had previously worked for the MT as a consultant, this letter invited her to move to Pittsburgh and operate an artistic workshop in “one of three slum areas the Hill, Homewood-Brushton, and the Northside.” Each of these areas was part of URA urban renewal plans. ↵

- Theodore Hazlett to Kenneth Dewey, July 2, 1969, box 30, folder 9, MTR. ↵

- William Farkas to John F. Hyle, December 7, 1970, box 9, folder 1, MTR. Farkas was the executive director of the Urban Renewal Authority. Hyle was the secretary and assistant controller of Mellon National Bank. Hazlett was copied in on the letter. ↵

- Arthur C. Twomey to Selma Burke, December 28, 1971, box 9, MTR. ↵

- “The Selma Burke Art Center, 1970–1972, by Selma Burke and Christine Fulwyle,” October 10, 1972, box 9, folder 2, MTR. ↵

- Burke Report for 1973 to James Kosinki, box 3, folder Carnegie Institute, SHBP. ↵

- For a thorough historicization of these protests, see Susan Cahan, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018). ↵

- “Second Week Report,” August 21–28, 1971, box 9, folder 1, MTR. ↵

- “Second Week Report.” ↵

- A sampling of coverage in the New Pittsburgh Courier includes “Afro-American Art Show Set,” November 6, 1971; “Distinguished Artists Attend Afro-American Fete Here,” November 20, 1971; and “Toki TYPES,” November 20, 1971. ↵

- Benny Andrews, “Charles White Was a Drawer,” Freedomways 20, no. 3 (1980); Burke, interview with Billops. ↵

- Selma Burke to J. Brooks Dendy, February 3, 1970, box 3, Folder Carnegie Institute, SHBP. ↵

- Burke, interview with Billops, 61. ↵

- The SSCAC began as a FAP CAC and had been in operation since 1941. ↵

- Margaret Burroughs to Selma Burke, November 8, 1971; Burke to Burroughs, November 11, 1971, both box 2, MTR. ↵

- Though Mbari has not received much scholarly attention, some members were also participants in other BAM-influenced art groups that are better documented. For instance, Ka was a member of the Harlem-based BAM group Weusi and the New York City Black feminist group Where We At, as well as Mbari. ↵

- Minutes from the faculty and staff meeting, June 6, 1973, box 6, SHBP. ↵

- Sponsored by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Harlem Children’s Art Carnival served primarily Black youth and was run by another prominent Black woman artist-educator, Betty Blayton-Taylor. See Souleo, “Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist” Hyperallergic, January 23, 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/343882/betty-blayton-taylor-reminiscence. ↵

- Dee Levister to Theodore Hazlett, September 13, 1973, MTR. ↵

- Dee Levister to Theodore Hazlett, September 13, 1973, MTR. ↵

- “Burke and Fulwyle,” October 10, 1972, box 9, folder 2, MTR. ↵

- Dee Levister to Theodore Hazlett, September 13, 1973, MTR. ↵

- When the MT pulled out, the SBAC lost its primary source of funding, which spelled financial ruin and exacerbated entrenched administrative failures. See Ron Suber, “Selma Burke Art Center Gets New Life,” New Pittsburgh Courier, May 16, 1981.There are many issues involved with the MT’s abrupt withdrawal that are beyond the scope of this paper. ↵

- Peterson’s official title was “program coordinator,” yet records indicate she was responsible for the bulk of the center’s operations. ↵

- Selma Burke Art Center Newsletter, Fall 1977, SHBP. ↵

- Rebecca Giordano, “Looking Back: Honoring Selma Burke and the SBAC,” in Women of Visions: Celebrating 40 Years, ed. Alex Taylor and Amanda Awanjo (Pittsburgh: University Art Gallery, forthcoming). ↵

About the Author(s): Rebecca Giordano is a PhD Candidate in the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh