Zombie Humanism, Generative AI Images, and Photography

PDF: Lewandowski, Zombie Humanism

Review of A Generated Family of Man

By The Flickr Foundation

London: Flickr Foundation, 2023, https://archive.org/details/a-generated-family-of-man

Critique of The Family of Man and its themes seems to return like clockwork every few years—each endeavoring to offer new insight on the subject. First shown from January 24 to May 8, 1955, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the exhibition curated by Edward Steichen intended to reveal the commonalities between peoples across the world through (mostly documentary and photojournalistic) photography. Part of The Family of Man’s enduring influence rests, however, not only on its public impact as a successful touring exhibition (on permanent display in Luxembourg since 1994) but also as a heuristic device for critiquing photography as a whole.1 In 1956, Roland Barthes appraised this type of humanist photography as a conservative abstraction that naturalized insidious elements of this “family”; in 1981, Allan Sekula dissected “the oft-repeated claim that photography constitutes a ‘universal language’”; in 2004, Abigail Solomon-Godeau viewed its permanent display as “a kind of Benetton ad” with advertising co-opting this “representational work”; in the 2010s, Ariella Azoulay provided a critical rehabilitation of the exhibition, arguing that it should be understood by its multiplicity and global citizenry.2 The list goes on.3

Why return once more to The Family of Man in the 2020s? Surely, nearly seventy years after the opening of the 1955 exhibition, the beloved punching bag of photographic critique could be replaced with something else—is there anything new to say about it? As Flickr arrives at its twentieth anniversary, the waning digital photographic depository seems concerned about cementing its legacy.4 Their new foundation has made The Family of Man the centerpiece of their New Curators Program, with three “A Flickr of Humanity” volumes “reinhabiting” the exhibition’s catalogue, with projects produced by university students in the United States and the United Kingdom.5 It is, ultimately, an educational tool for undergraduate students exploring images of contemporary issues in the United States (volume 1), learning about the intricacies of copyright (volume 2), and charting the limits of generative artificial intelligence (AI) (volume 3). Rather than critiquing the dated form of humanism in the exhibition’s content, the projects hollow out The Family of Man to its form alone. Each Flickr volume inserts different sets of images into the recognizable format of the exhibition’s famous catalogue, which has never been out of print (fig. 1).6 Flickr’s volumes 1 to 3 appear to have been printed as well, but entirely for internal use and promotion of the Foundation’s activities;7 only volume 3 was presented fully online, uploaded as a PDF on the Internet Archive (a nonprofit digital library and archive) and with the individual images uploaded in a Flickr gallery (fig. 2).8 The external, public reach of this publication outside the Flickr Foundation and the academic groups involved is tiny, however, with only a handful of views recorded.9

In A Generated Family of Man (volume 3), Goldsmiths, University of London, design students (and Flickr interns) Juwon Jung and Maya Osaka generated images over several weeks in the summer of 2023. They attempted to recreate around half of the photographs that appeared in The Family of Man publication using Microsoft’s Bing Image Creator through two different methods. For the first method (human prompts), the team wrote the prompts themselves and finessed them a further time if needed; for the second method (AI prompts), they “fed screenshots” of actual Family of Man photographs into Image-to-Caption (an AI caption generator intended for marketing social-media posts), then selected one of the three “captions” produced for an image and used it as the text prompt for Image Creator.10 This method, chosen for its “cheesy Instagramesque captions, including emojis and hashtags,” reflects the predominant commercial usages of this AI technology and the type of content employed for AI training sets.11 The images made through the AI prompts often appear in color throughout A Generated Family of Man precisely due to this lack of control—what a commercial image-to-text caption generator is trained to perceive and formulate is not a thorough descriptive text. Famously, the only color photograph in the original Family of Man exhibition (which does not appear in the catalogue) was a massive backlit transparency of an H-bomb test blast, displayed in the final room. Blake Stimson describes this placement as a “moral choice” for the viewer, in which “nuclear holocaust was set up as the alternative to living the collective fantasy of a family of man.”12 In A Generated Family of Man, the symbolic equivalent (AI) is diffuse and peppered throughout the book. Compared to Steichen’s stark, concrete warning, growing anxiety about what generative AI images’ aesthetic mimicry of photography could mean to society is an unfocused existential crisis.

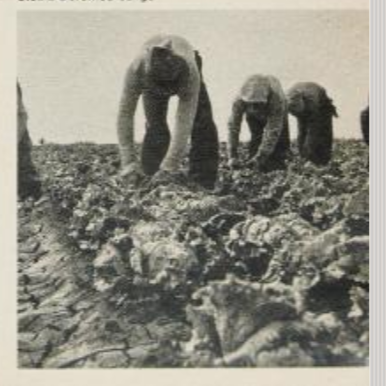

Even considering the rapid developments in generative AI, though, the 2023 images seem crude. Faces, hands, and limbs are bizarrely contorted or multiplied in monstrous configurations, a typical, humorous giveaway for generative AI images during their early development.13 The AI prompts often present something detached from the original subject. For example, instead of seeing workers cutting produce in Dorothea Lange’s 1935 photograph (fig. 3), the figures are interpreted as elephants (captioned “Behold the mighty elephants, creating beautiful footprints in the soft earth”) (fig. 4).14 Even without the Bing watermark, none of these 2023 images will dupe the viewer into thinking these are real photographs. (Those that are genuine, including the copyright-free NASA’s 1972 “Blue Marble” and some of Dorothea Lange’s Farm Security Administration [FSA] work, are so well known they hardly require captioning at all.) Rather than an attempt to protect copyright, these watermarks are part of an emergent industry standard to identify generative AI images.15

The failure to recreate the photographs more convincingly is, in part, due to the program. Bing Image Creator uses OpenAI’s DALL-E, with a number of content filters put in place to remove content and block prompts that include violence, sexual imagery, and named public figures.16 Its dataset consisting of over 250 million images is stated, in purposefully vague terms, to be drawn “from a combination of publicly available sources and sources that we licensed,” including major stock image providers.17 A paper published by OpenAI staff in 2022 underlines the problems with this dataset: it reproduces existing biases, particularly in commercial photography, with an overrepresentation of “people who are White-passing and Western concepts generally,” along with stereotypical representations of gender and race (prompts illustrating this include “lawyer,” “nurse,” “builder,” and “flight attendant”).18 Though DALL-E is not based on the Imagenet database (which Midjourney uses) that has been a subject of high-profile critique in the art world,19 it still reinforces how bias is an inherent part of any image set.

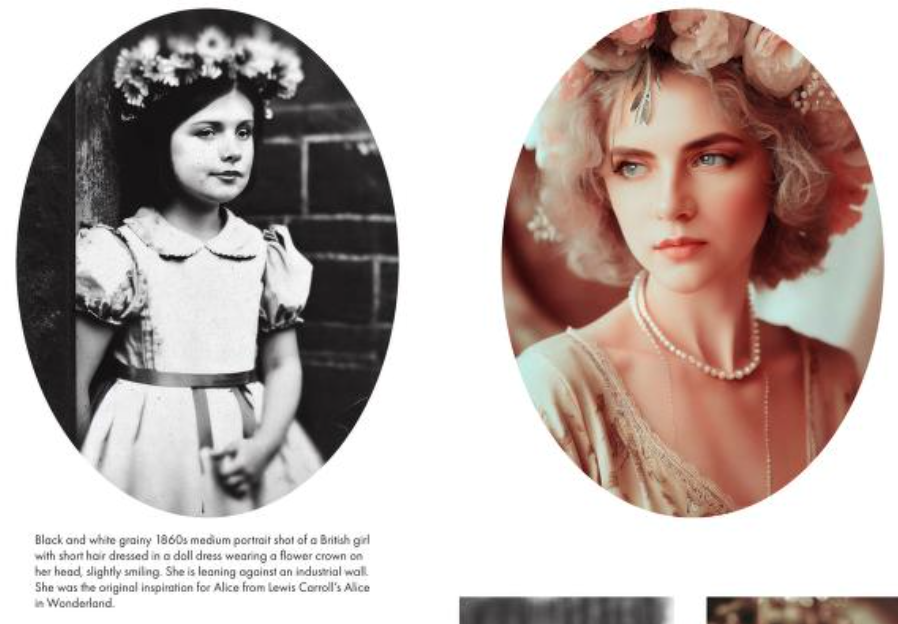

In A Generated Family of Man, as the Flickr team notes, the biases are striking.20 Although most of the 484 photographs in The Family of Man catalogue were taken from the 1930s to 1950s, they extend as far back as the nineteenth century, including an 1860 photograph of Alice Liddell by Lewis Carroll (fig. 5).21 Even for this photograph, firmly out of copyright, the human prompt results in an odd cosplay of Disney’s Alice in Wonderland from 2010 (fig. 6, left); the shellacked face and flower crown, made up of something that looks like gerbera daisies (not cultivated in the UK until the 1890s) look distinctly anachronistic, perhaps even a touch like the musician Lana Del Rey.22 The AI prompt produces an even more outlandish interpretation in airbrushed color, reflecting the bias toward late 2000s and 2010s images (possibly including the eclectic aesthetics of Tumblr) (fig. 6, right).23

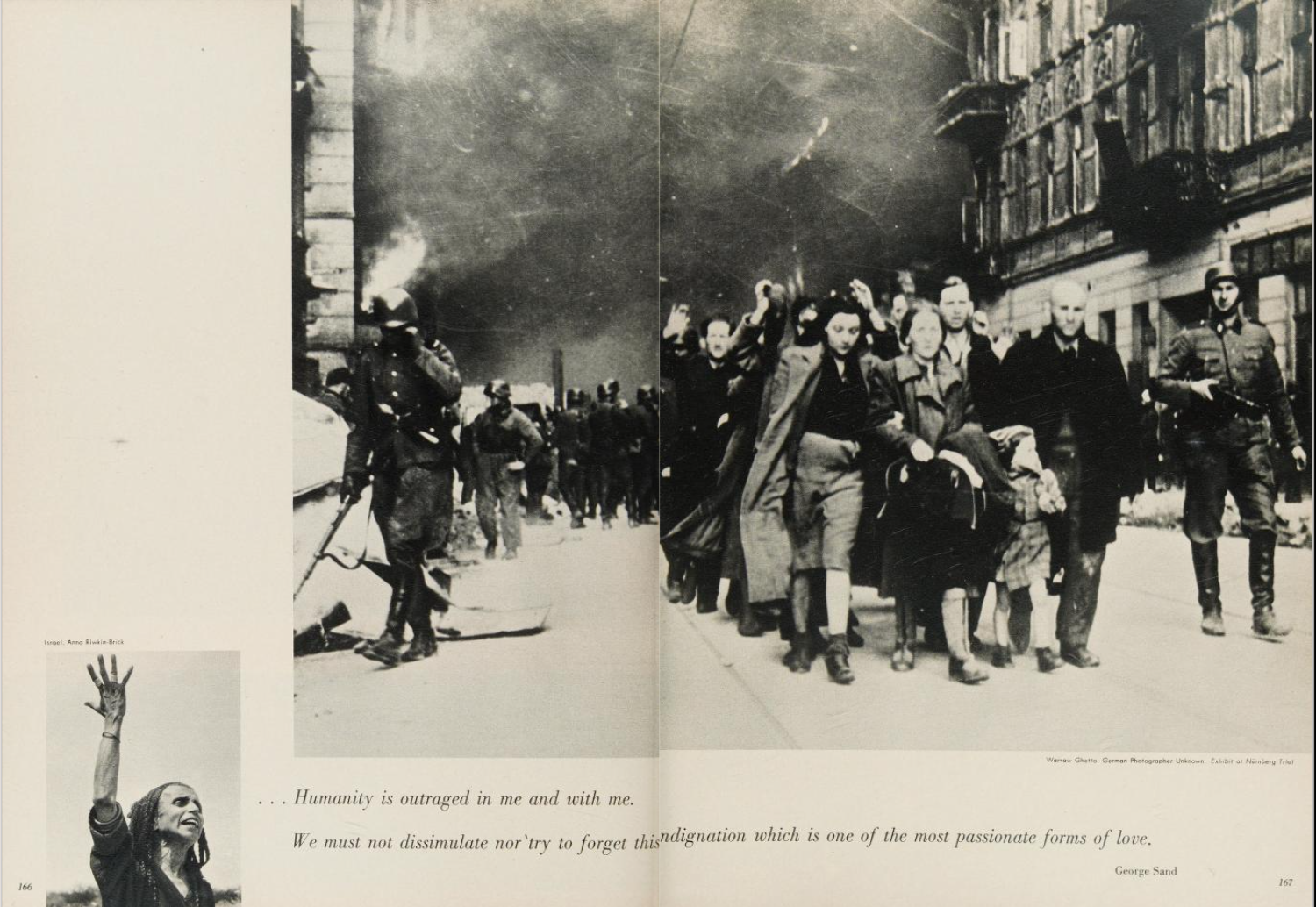

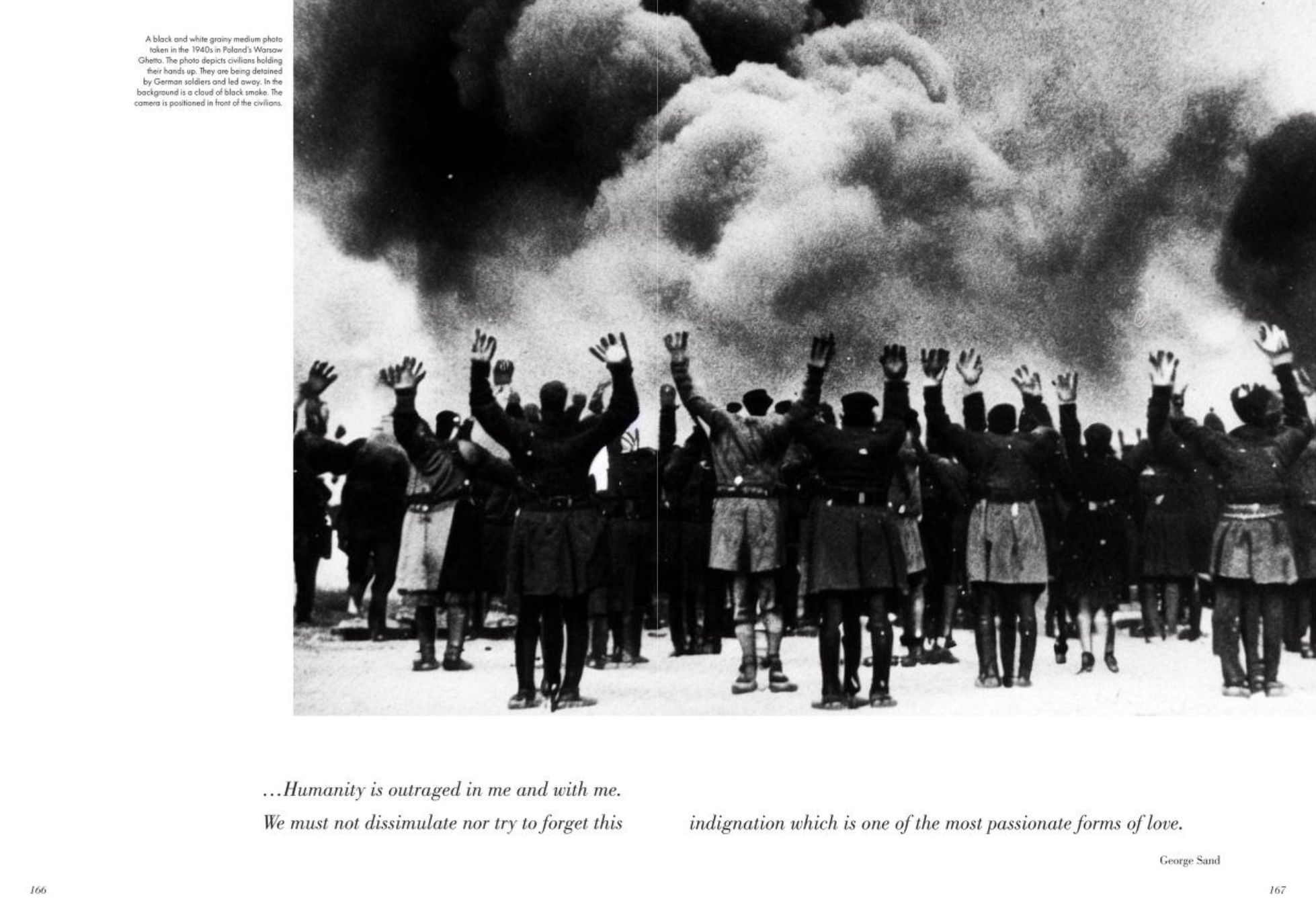

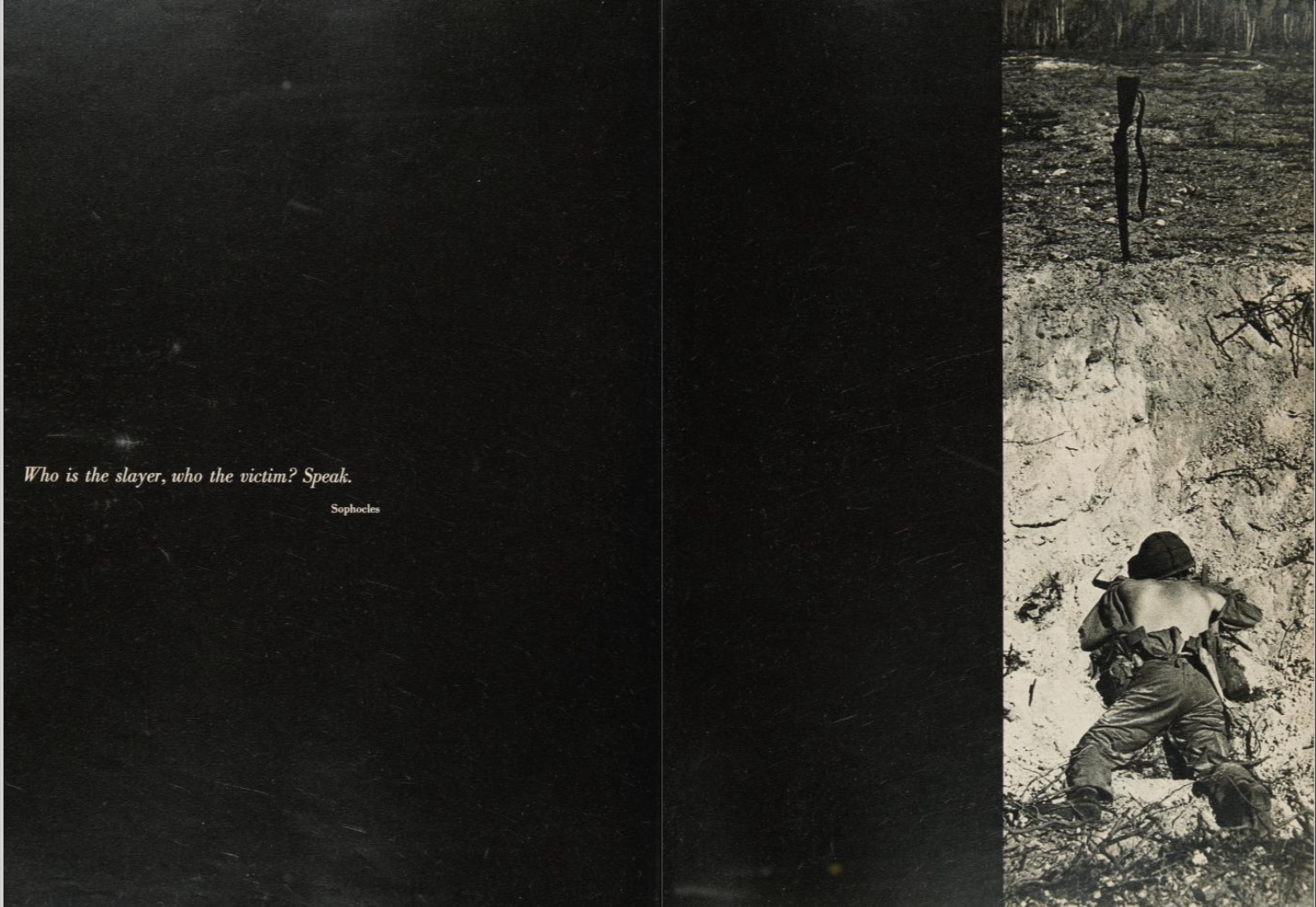

Beyond such innocuous examples, however, disturbing contrasts appear when these programs—which have been tailored for commercial, illustrative uses—are prompted to create imitations of documents or photojournalism. The Family of Man’s only image directly related to the Holocaust, the 1943 photograph showing Jewish families forced out of the Warsaw ghetto by Nazis (fig. 7), is thankfully only represented through a human prompt and not an AI one.24 The human prompt–generated image related to the Warsaw ghetto photograph shows the subject from the opposite perspective, with backs facing the viewer, but the hands are inverted with the palms up (fig. 8). Though the prompt specifies “civilians,” Image Generator produced an image largely of identical men, with no children. The suggestion in the prologue that generative AI images can “restore historical images” is worrying, since it can also distort the past in our own contemporary image.25 Another photograph by Raphael Platnick, showing a dead US soldier lying face down against the side of a trench during the 1944 battle of Eniwetok (fig. 9), is translated via the human prompt to a dynamic head-on perspective of a helmet (fig. 10, left).26 The AI prompt produced a lifestyle magazine–type image of a blonde woman against a field, captioned: “Taking a moment to connect with nature’s embrace 🌾 #FieldOfDreams #GroundedInTheWilderness #SerenityInTheGrass” (fig. 10, right). These bizarre AI prompt interpretations are found throughout A Generated Family of Man and serve to reveal the limitations (and motivations) of what AI text-to-image and image-to-text models have largely been trained to input and output.

Generative AI images of contemporary conflicts have caused outcry over the past year: in April 2023, Amnesty International used generative AI images to illustrate violence against students for a report on police reform in Colombia; in November 2023, Adobe Stock sold real photographs alongside generative AI images illustrating the Israeli strikes on Gaza; in May 2024, a Ukrainian YouTuber’s likeness was reported as being used to promote pro-Russian sentiments to a Chinese audience.27 The pervasive distrust in images is, of course, not confined to AI. Even real photographs have been misrepresented as showing other events or dismissed as “Photoshopped.” Ron Haviv’s 1992 photograph of a Serbian paramilitary kicking a murdered civilian in Bosnia has been co-opted both in the 1990s and as recently as 2014, when it circulated on Facebook, purporting to show Ukrainian soldiers in Crimea.28 To combat misappropriation, Haviv’s color slides were meticulously digitized in 2022 with detailed image authentication. The challenge that photorealistic generative AI imagery represents is not to replace photojournalism; it is to discredit it. As Fred Ritchin cautions, it is to further break photography’s perceived relationship with reality.29 Would a photograph of Alan Kurdi motivate political change today, or would it be dismissed as AI?

The project team wrote that A Generated Family of Man was designed for “the ideal situation: the reader would have an original The Family of Man catalogue to hand to compare and contrast the original photographs and generated images side by side.”30 Doing so illustrates the contrast in tones between the spiritual postwar humanism curated by Steichen and its absurdist, irreverent AI interpretations. In my doctoral research, I pointed to a resurgence of humanism and the celebration of the “everyday” in photography through the rise of social media and mass amateurization between 2000 and 2020.31 Written before a flurry of op-eds about generative AI images’ existential challenge to photography, I discussed how a new and altered form of humanist photography had become branded, exploited, and commodified. As James Bridle explores, the data gathered and analyzed from the “everyday” moments and behaviors of the masses create enormous profits for companies.32

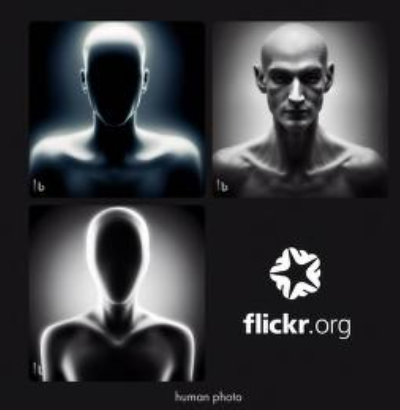

Twenty-first-century humanism has focused on neoliberal individualism, subjectivity, and first-person narratives, emphasizing the voices of both subject and author. While this humanist resurgence may be criticized as merely gestural, the subsequent images produced by programs like DALL-E and Midjourney artificially reanimate this digitally overrepresented 2010s culture, a mixture of scraped photographs from search engines, social-media platforms, and stock photography. This is what I would term “zombie humanism,” incidentally producing the same commercially motivated “everyday” tropes but presenting them untethered from historical, political, or photographic contexts (a nineteenth-century Alice Liddell revivified through Tumblr; a 1940s dead soldier transmorphed into a 2010s influencer). The eerie, faceless solitary shadow figures on the back cover is, as Jung writes, one of the many unsettlingly inhuman results that were generated from typing “human” into Image Generator in a failed attempt to connect to The Family of Man’s themes (fig. 11).33

A reference to Roland Barthes’s punctum in the prologue by Fattori McKenna is critical of generative AI’s hollow imagery but is ultimately misapplied.34 It is not that there is some elusive, specific aesthetic detail in a photograph that causes a personal, emotional “prick” to the viewer (not all, or many, photographs will have a punctum for the viewer).35 It is the fact that these images are not photographs; there is no punctum or even studium (a detached political, cultural, or historical interest in a photograph). Generative AI images may aspire to visually resemble photographs, but crucially they have no medium-specific relationship to reality (“the Photograph is pure contingency and can be nothing else,” in the Barthesian view).36 Barthes’s 1967 essay “Death of the Author” might be a more relevant though flippant reference; the catalogue’s afterword (a reprinted article from Lawfare, not written for the project) by Flickr’s board chair Ryan Merkley repeats the argument continually made by tech companies that AI is a “transformative use” of materials, which elude the author’s ownership.37 Merkley leadingly asks, “Is it labor theft if you find an unanticipated and unrealized value in something by combining it with other works and processing it?”38 A number of ongoing lawsuits might challenge this premise.39

It may be tempting to view generative AI images through the lens of posthumanism, which, according to Rosi Braidotti, could move past the “lethal binaries” of humanism/antihumanism toward “an eco-philosophy of multiple belongings.”40 Rather than a Braidottian understanding of posthumanism, liberated from the conservative and anthropocentric humanism associated with postwar humanist photography,41 there is instead a risk of further entrenching harmful humanist biases, reifying what people want to see or believe. This is neither a return to the “old humanist institutions that created the conditions for greater equality,” which Stimson reminisced about, nor Azoulay’s reformed humanism, which rejects postwar humanism’s implicit white colonial man in favor of the heroic figure of the citizen.42 Instead, generative AI’s zombie humanism is, at best, as per Barthes’s 1956 text, a further naturalization of ingrained human biases. At worst, however, it inhabits the visual signifiers of humanism while actively discrediting the photojournalistic corpus that documents our shared human history.

Cite this article: Helen Lewandowski, “Zombie Humanism, Generative AI Images, and Photography,” review of A Generated Family of Man, Flickr Foundation, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 10, no. 2 (Fall 2024), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19237.

Notes

- The Family of Man toured museums in the United States until 1958 and was acquired by the United States Information Agency for international touring until 1963. Four touring “copies” were produced and visited thirty-seven countries, including Afghanistan, Colombia, Cuba, France, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Kenya, Laos, Poland, South Africa, Sweden, and Yugoslavia. One touring copy of the exhibition was presented to the Government of Luxembourg for a permanent display at the Common Market Headquarters in 1965. (For a full list, see “Internationally Circulating Exhibitions,” Museum of Modern Art, accessed September 21, 2024, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/icelist.pdf). Since 1994, Clervaux Castle in Luxembourg has displayed this touring copy of The Family of Man as a permanent exhibition, which entered into the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme in 2003. ↵

- Roland Barthes, “The Great Family of Man,” in Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012), 196–99; Allan Sekula, “The Traffic in Photographs,” Art Journal 41, no. 1 (Spring 1981): 19; Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “The Family of Man: Refurbishing Humanism for a Postmodern Age” (2004), in Photography after Photography: Gender, Genre, History (London: Duke University Press, 2017), 56; Ariella Azoulay, “‘The Family of Man’: A Visual Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” in The Human Snapshot (Berlin: LUMA Foundation; Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College; Sternberg, 2013), 19–48; Ariella Azoulay, “Photography Is Not Served: ‘The Family of Man’ and The Human Condition,” in Documentary Across Disciplines, ed. Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg (London: MIT Press, 2016), 110–41. ↵

- There is not enough space to trace every reference in this short review, but other influential studies and critiques include Christopher Phillips, “The Judgment Seat of Photography,” October 22 (Autumn 1982): 27–63; Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995); Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). ↵

- Yahoo acquired the pioneering startup Flickr in 2005; by 2016, when Verizon announced acquisition of Flickr’s struggling parent company, Flickr was already seen as an underinvested relic, outperformed by Instagram (launched in 2010) and other social-media image-sharing platforms. In 2018, Flickr was sold off by Verizon to SmugMug, a subscriber-based online image host for professional photographers. After its cultural relevance and popular usage peaked in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Flickr has been in decline. From 2019, overall upload limits (of one thousand items) and private upload limits (of fifty nonpublic limits) were put in place on Flickr, excepting copyright-free material in excess of this. See “Free account limit changes and enforcement,” Flickr help page, accessed September 21, 2024, https://www.flickrhelp.com/hc/en-us/articles/13690320471060-Free-account-limit-changes-and-enforcement; and Kaitlyn Tiffany, “Flickr will soon start deleting photos—and massive chunks of internet history,” Vox, February 6, 2019, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/2/6/18214046/flickr-free-storage-ends-digital-photo-archive-history. ↵

- Flickr was launched in 2004; the Flickr Foundation was launched in September 2022. For the “A Flickr of Humanity Project,” see https://www.flickr.org/programs/new-curators/a-flickr-of-humanity. ↵

- The Family of Man catalogue, initially designed by Leo Lionni, is in its sixteenth printing (as of 2021) of its thirtieth-anniversary edition and has never been out of print; its sales still support an acquisitions fund for MoMA’s collection. ↵

- Flickr president Ben MacAskill, for example, distributed 250 printed copies of volume 2 at a CEO membership group event (a Tugboat Institute Summit); see “A Flickr of Humanity: First project in the New Curators program,” June 26, 2023, Flickr Foundation (blog), https://www.flickr.org/blog-a-flickr-of-humanity. ↵

- See Flickr Foundation, “A Generated Family of Man,” accessed September 21, 2024, https://www.flickr.com/photos/flickrfoundation/albums/72177720310475166. Another Flickr gallery shows images included in volume 2, but the full book or layout was not published online; see Flickr Foundation, “Flickr of Humanity,” accessed September 21, 2024, https://www.flickr.com/photos/flickrfoundation/galleries/72157721894129434. ↵

- Toward this review, I consulted A Generated Family of Man (volume 3) on the Internet Archive, accounting for a portion of the view count numbering 136 as of September 8, 2024. ↵

- Maya Osaka, “Creating A Generated Family of Man,” Flickr Foundation (blog), September 25, 2023, https://www.flickr.org/creating-a-generated-family-of-man. ↵

- Osaka, “Creating A Generated Family of Man.” ↵

- Stimson, The Pivot of the World, 101. ↵

- This “uncanniness” is acknowledged in the texts of A Generated Family of Man, with Flickr Foundation Cofounder and Executive Director George Oates writing, “Perhaps the smears and guesses will disappear or ultimately convince us later.” A Generated Family of Man (London: Flickr Foundation, 2023), 5–6, https://archive.org/details/a-generated-family-of-man. ↵

- Edward Steichen, The Family of Man, 30th anniversary ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 65; Generated Family of Man, 67. ↵

- The Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI), founded by Adobe in 2019, is an industry-led association with more than three thousand members, including Microsoft. In 2021, the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) was founded by Microsoft and Adobe to establish “content provenance and authenticity”; these “Content Credential” standards (such as watermarks that include metadata) are promoted by CAI. See “About,” Coalition for Content Provenance and Authority, accessed September 21, 2024, https://c2pa.org/about and “Our Members,” Content Authenticity Initiative,” accessed September 21, 2024, https://contentauthenticity.org/our-members. ↵

- DALL-E is a text-to-image model first developed in 2021, with a new version, DALL-E 2, released eventually to the public in 2022. In late 2023, an updated model, DALL-E 3, was launched. ↵

- Pamela Mishkin et al., “DALL·E 2 Preview—Risks and Limitations,” GitHub, 2022, https://github.com/openai/dalle-2-preview/blob/main/system-card.md. ↵

- Mishkin et al., “DALL·E 2 Preview.” ↵

- Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen’s ImageNet Roulette (2019) and work criticizing AI training sets have particularly brought these issues to light in the art world through exhibitions. See also Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen, “Excavating AI: The Politics of Training Sets for Machine Learning,” AI Now Institute, New York University, September 19, 2019, https://excavating.ai. ↵

- Tori McKenna, “When Past Meets Predictive: An Interview with the Curators of ‘A Generated Family of Man,’” Flickr Foundation (blog), September 29, 2023, https://www.flickr.org/when-past-meets-predictive-an-interview-with-the-curators-of-a-generated-family-of-man. ↵

- The project team presented their own analysis of the publication’s contents: Maya Osaka, “A Flickr of Humanity: Who Is The Family of Man?,” Flickr Foundation (blog), July 10, 2023, https://www.flickr.org/a-flickr-of-humanity-who-is-the-family-of-man; an analysis of the exhibition’s 503 photographs was previously explored in Solomon-Godeau, “The Family of Man.” ↵

- Generated Family of Man, 189; Steichen, The Family of Man, 191. ↵

- Juwon Jung notes that the generative AI images from the image-to-text captions all “looked like they were from the early Instagram-era in 2010,” in “Making A Generated Family of Man: Revelations about Image Generators,” Flickr Foundation (blog), September 29, 2023, https://www.flickr.org/making-a-generated-family-of-man-revelations-about-image-generators. ↵

- Solomon-Godeau, “The Family of Man,” 49; Steichen, The Family of Man, 166–67; Generated Family of Man, 166–67. ↵

- “Synthetic generation has the potential to restore historical images that might have been damaged, burnt, or partially missing, offering us the chance to relive moments of history with credible visual data.” Generated Family of Man, 6. ↵

- Steichen, The Family of Man, 181; Generated Family of Man, 180. ↵

- Jo Lawson-Tancred, “Amnesty International Faces an Outcry from Photographers over Creating A.I.-Generated Images of Protestors,” Artnet News, May 4, 2023, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/amnesty-international-faces-backlash-from-photographers-for-creating-a-i-generated-images-of-protestors-2294348; Cam Wilson, “Adobe Is Selling Fake AI Images of the War in Israel-Gaza,” Crikey, November 1, 2023, https://www.crikey.com.au/2023/11/01/israel-gaza-adobe-artificial-intelligence-images-fake-news; Fan Wang, “How AI Turned a Ukrainian YouTuber into a Russian,” BBC News, May 14, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c25rre8ww57o. ↵

- Josh Raab, “In Ukraine, A Battle of Words and Images,” TIME, July 8, 2014, https://time.com/3810444/ukraine-fake-images-claim; “The DJ and the War Crimes: Archive,” Rolling Stone, December 28, 2022, https://investigation.rollingstone.com/dj-photo-war-crimes-bosnia/archive. ↵

- Fred Ritchin, “When Is a Photo Not a Photo? The Looming Specter of Artificially Generated Photographs,” Vanity Fair, February 15, 2023, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2023/02/the-looming-specter-of-artificially-generated-photographs; Amanda Darrach, “Q&A: Fred Ritchin on AI and the Threat to Photojournalism No One Is Talking About,” Columbia Journalism Review, March 1, 2023, https://www.cjr.org/the_media_today/fred_ritchin_ai_photojournalism.php. In an essay for a forthcoming book, I explore the controversies related to digital photography, with previous remarks made by Ritchin (and others) from the 1980s onward and their influence on how photograph-like generative AI images have been received: “The Ontology of the Digital Photograph,” in Dissident Practices: Posthumanist Approaches to Critiques of Political Economy (London: Bloomsbury, forthcoming). ↵

- Osaka, “Creating A Generated Family of Man.” ↵

- Helen Lewandowski, “The Aesthetics and Distribution of Photojournalism, 2000 to 2020” (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2023). ↵

- James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (London: Verso, 2018), 229–30. ↵

- Jung, “Making A Generated Family of Man.” ↵

- Generated Family of Man, 6–7. ↵

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (London: Vintage, 1993), 27. ↵

- Barthes, Camera Lucida, 28, 34. ↵

- Ryan Merkley, “On AI-Generated Works, Artists, and Intellectual Property,” in Generated Family of Man, 192–97, https://archive.org/details/a-generated-family-of-man (originally printed in Lawfare, February 27, 2023, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/ai-generated-works-artists-and-intellectual-property). ↵

- Merkley, “On AI-Generated Works, Artists, and Intellectual Property,” 195. ↵

- Among the lawsuits brought against companies for the copyrighted material allegedly used for generative AI training sets, a group of artists raised a case against Midjourney in 2023 that, as of writing, is still ongoing. See Blake Brittain, “How Copyright Law Could Threaten the AI Industry in 2024,” Reuters, January 2, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/how-copyright-law-could-threaten-ai-industry-2024-2024-01-02; Torey Akers, “DeviantArt and Midjourney Deny Wrongdoing in Copyright Infringement Lawsuit over in AI Image Generators,” Art Newspaper, May 10, 2024, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/05/10/deviantart-midjourney-stable-diffusion-artificial-intelligence-image-generators. ↵

- Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2013), 37, 49. ↵

- For more on this, see Helen Lewandowski and Lisa Moravec, “Humanism after the Human: An Introduction,” Photography and Culture 14, no. 2 (June 14, 2021): 125–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/17514517.2021.1925006. ↵

- Blake Stimson, “What Was Humanism?,” Either/And, May 30, 2013, archived February 1, 2023, at https://web.archive.org/web/20230201054728/http://eitherand.org/humanism-dead/what-was-humanism; Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone, 2008). ↵

About the Author(s): Helen Lewandowski is a PhD graduate of The Courtauld Institute of Art, London.