A Research Portal for American Watercolors, Prints, and Drawings 1850–1925: A Source for Obscure Catalogues, Artists’ Societies, and Women Artists

New resources for the study of American works on paper are available at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s website (philamuseum.libguides.com/AmericanWatercolors), a site that promises to feed research on individual artists working between 1850 and 1925, and on topics such as women artists, the art market and collecting, the social life of artists, and the development of all the graphic arts in this period (fig. 1). The project was born as an extension of my 2017 exhibition catalogue, American Watercolors in the Age of Homer and Sargent, which tells the story of the American watercolor movement from the foundation of the American Watercolor Society (AWS) in 1866 through about 1925.1 The book and the exhibition traced the sudden rise in popularity of watercolor in the United States in this period, with all the tangled social, economic, artistic, and personal forces at play. Individual artists and their subjective choices were at the center of this book, but their work was woven into the larger context of the struggle to make a living in the United States as a professional artist; the influence of illustration and decorative design as a livelihood based on the use of watercolor; the rise of the club movement in support of artists’ status and morale (and the AWS as a model and incubator of many subsequent clubs); the impact of “impressionist” aesthetics sympathetic to watercolor technique; and the new place of women (so often watercolorists) in the American art community.2 However, the book, although hefty, could not contain the extensive period bibliography cited in the notes, so it seemed both sensible and flexible to create some kind of online supplement that could be expanded over time.

I was encouraged at this time by the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s push into digital publication as it prepared an innovative catalogue of selections from the famed John G. Johnson Collection. This online publication added detailed scholarly apparatus (provenance and exhibition history) to thorough analysis of each painting, and it linked to digitized scans of relevant archival primary sources.3 Although the construction of this publication was complex, its flexibility has tremendous appeal: apart from the merit of worldwide access to the material, information can be revised or supplemented over time. Meanwhile, as I considered the virtues of digital publication, the rapid scarcity of the watercolor book—which sold out during the run of the exhibition—made wider access to both published and unpublished appendices increasingly desirable.

I started small, searching for a simpler and less expensive way to post the auxiliary bibliography online, and turned to my colleague Karina Wratschko, the museum’s digital librarian, whose friendly face appears on the homepage as a contact for help. We could not add to the old platform because the museum’s website was in the process of being rebuilt, so we had to strike out on our own. With the principles of sharing, findability, and revision in mind, we opted to create a static website via Jekyll, with free hosting on GitHub Pages. We selected one of their free design templates, plugged in a Winslow Homer watercolor from the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s collection as a banner illustration, and enlisted the editor of the watercolor book, Kathleen Krattenmaker, to help craft introductory texts. Wratschko recommended using the Internet Archive to host any scanned materials because of its mission to provide permanent access for researchers, historians, and scholars to historical collections that exist in digital format.

The rich but unwieldy scale of the bibliography resulted from my almost forty years of intermittent research on the topic, beginning with reviews and articles I tediously collected as photocopies and microfilm printouts in the 1970s as part of my dissertation research. Bits and pieces of my thesis, “Makers of the American Watercolor Movement, 1860–1890,”4 particularly on the watercolors of John La Farge, Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, and the American Pre-Raphaelites, were developed and published over the next two decades, but the grand scheme of building a book and an exhibition did not become a reality until after I arrived at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2002.5 Around 2015, as the exhibition was finally taking shape, I discovered Zotero and began to dump decades of periodical references into its database template. If you are not familiar with this free, cloud-based, open-source software, know that it is a gift to anyone building a bibliography. Your bibliographic information can be sorted, searched, and downloaded in multiple ways, using various citation forms, making the software ideal for collaborative teams or wiki-type compilations. We downloaded this Zotero bibliography to our new watercolor website in three fixed formats: by date, by author, and by journal title. Those familiar with the software (which is easy to navigate) can also search and sort the original database in other ways, and anyone can add new material, if desired.

At the moment, this bibliography includes more than nine hundred references, spanning watercolor exhibition reviews and related artist studies, newspaper clippings, and illustrated journal articles, mostly from 1850 to 1925, with the richest compilation of entries from 1870 to 1900, during the peak of the watercolor movement. For assistance with adding older citations and a steadfast and creative search for additional reviews, which totaled up to several years of effort, I am grateful to the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Center for American Art summer fellows James Denison, Abby Eron, Ramey Mize, Lauren Palmor, Corey Piper, Melanie Saeck, and Brittany Strupp, and Barra Foundation fellows Laura Fravel, Kelsey Gustin, Jennifer Stettler Parsons, Naomi Slipp, and Amy Torbert.

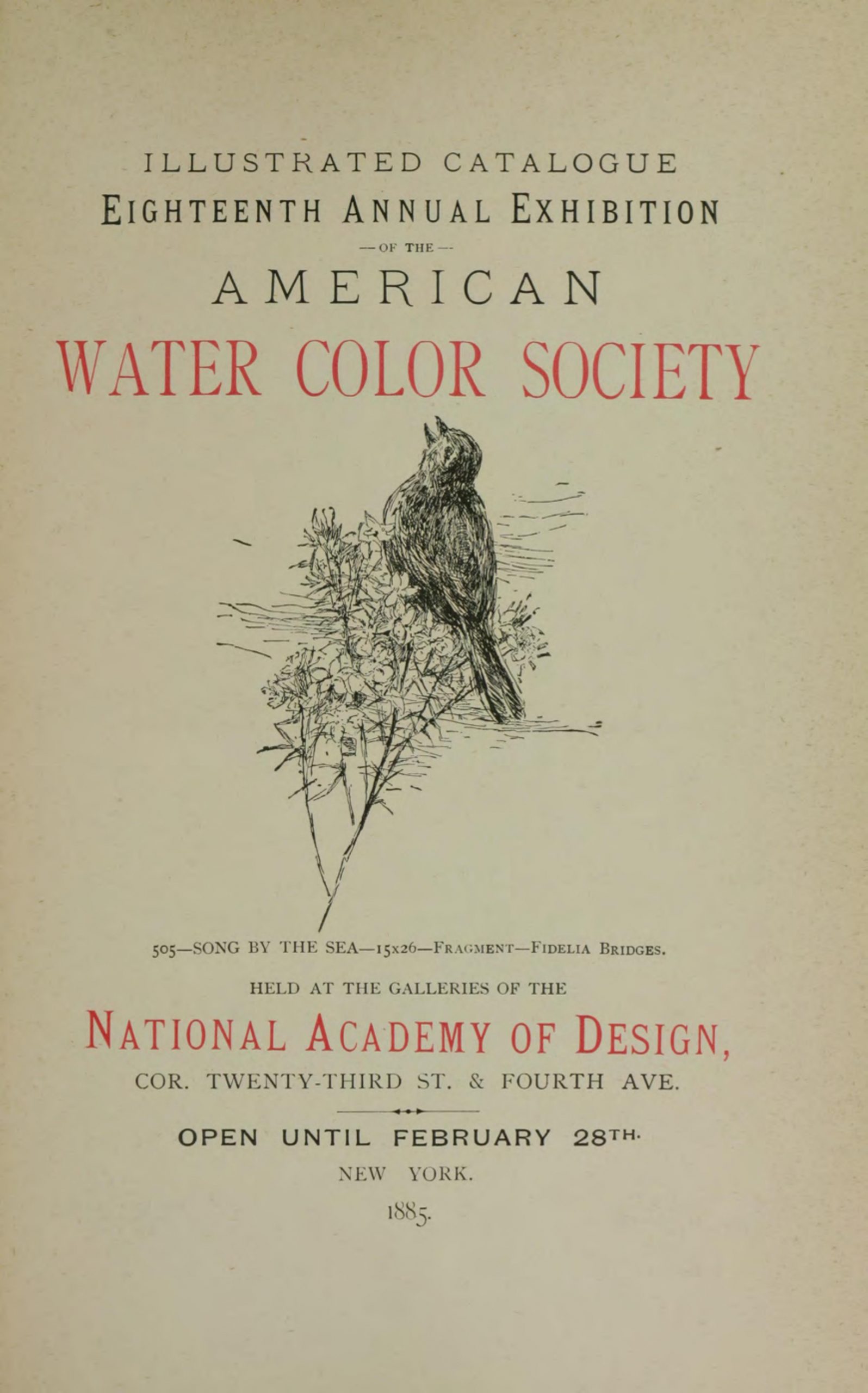

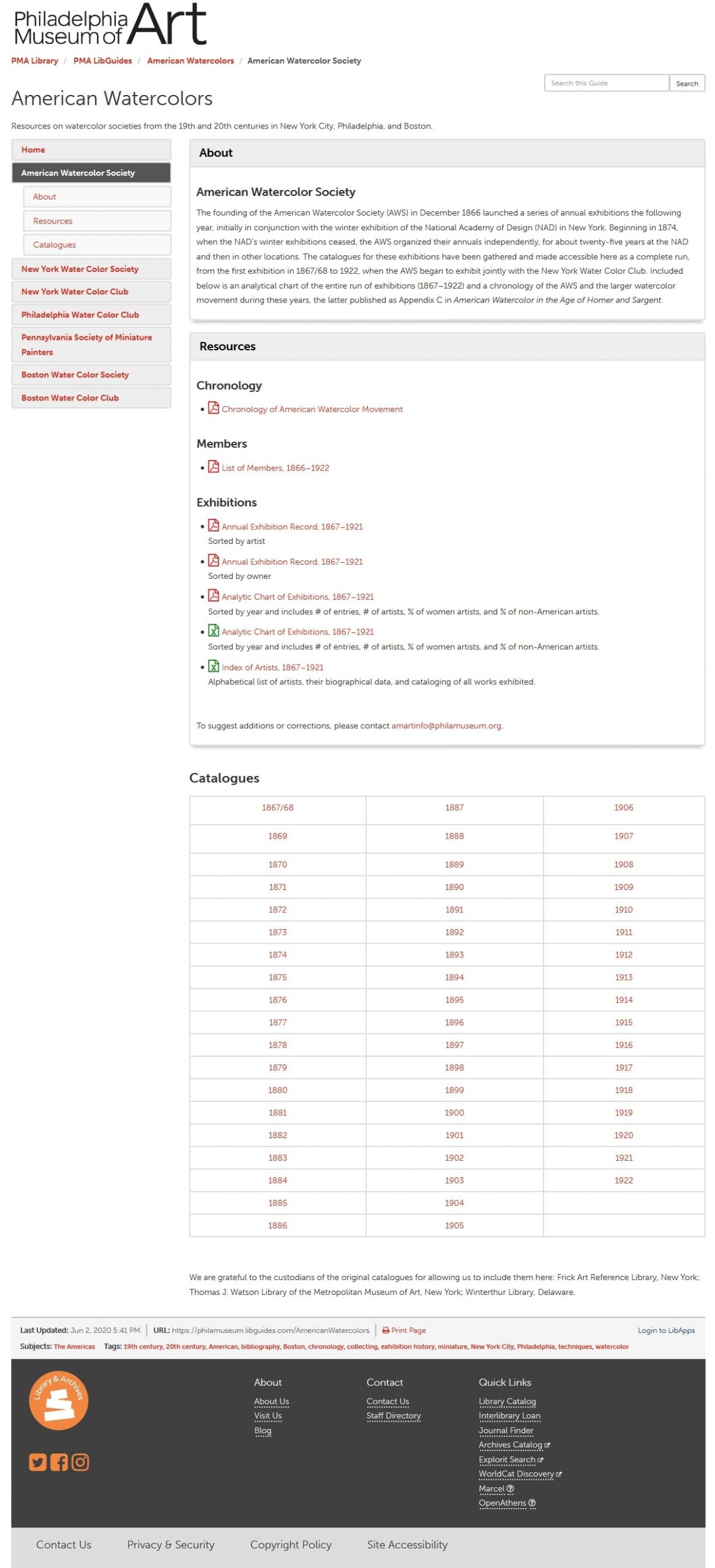

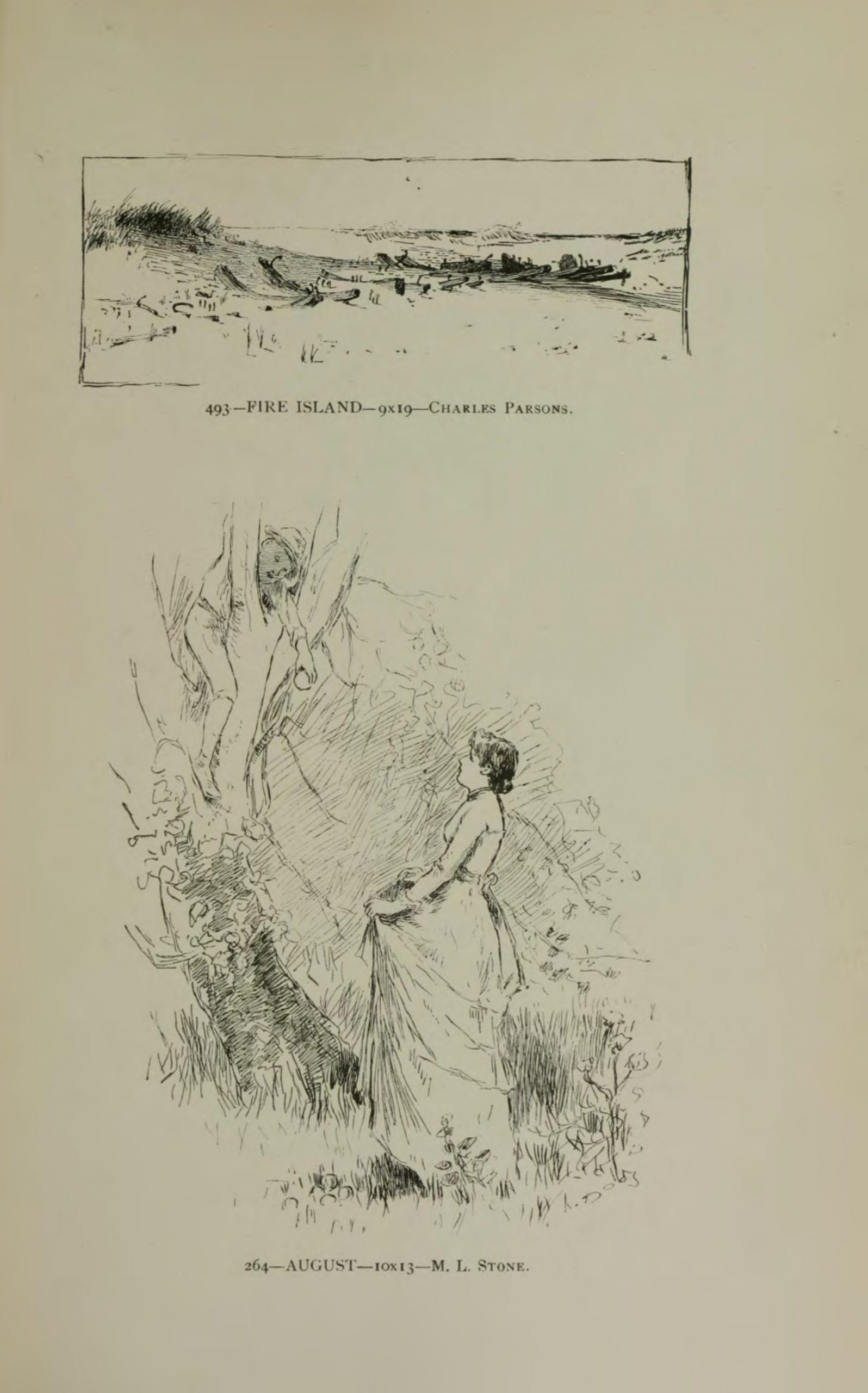

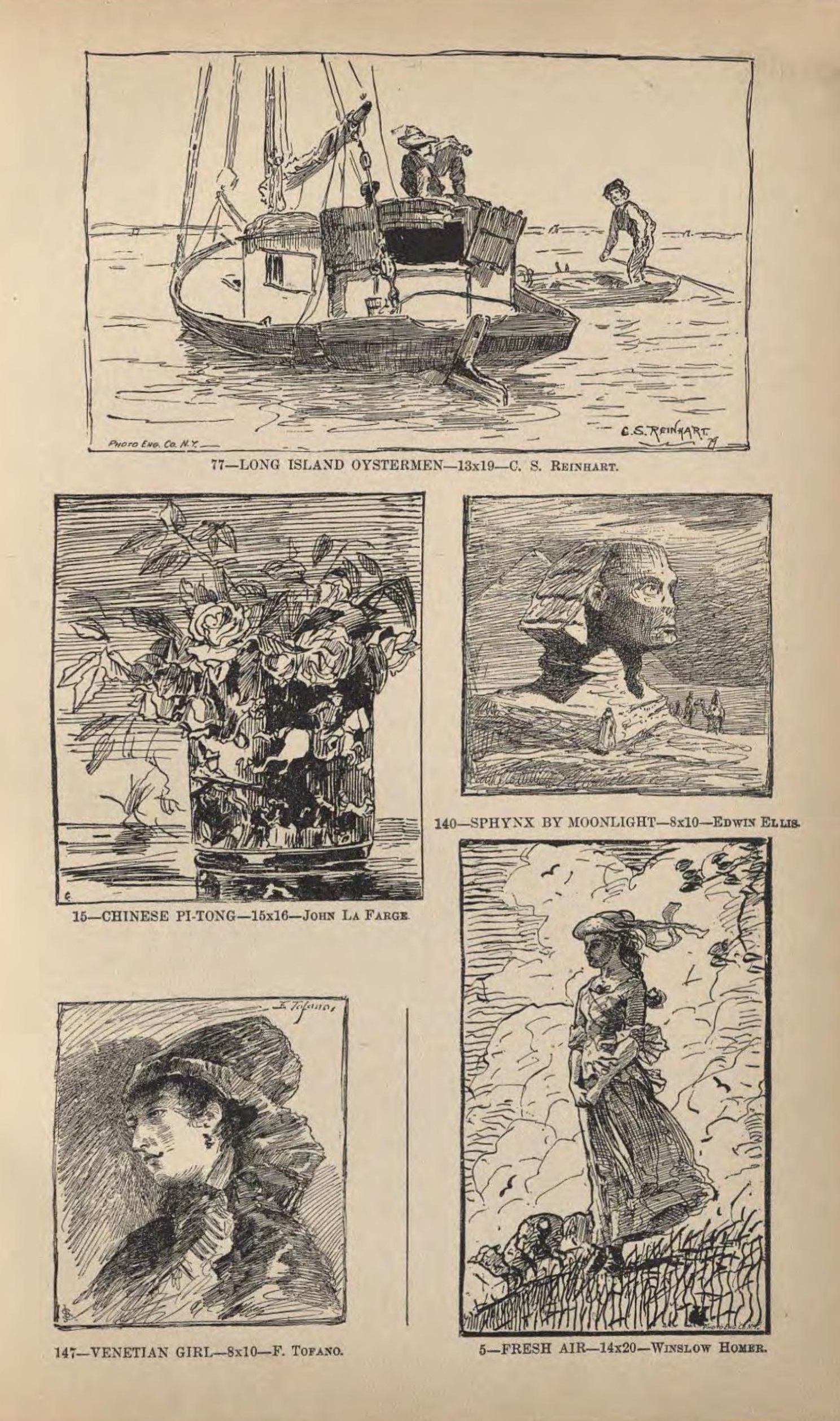

As part of my original research in the 1970s, I collected copies of the catalogues of the AWS annual exhibitions, from the first in 1867 through the 1890s (fig. 2); for this website project, I expanded the reach through 1922.6 No cumulative record of these exhibitions had ever been published, as had been done for the annuals at the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and many other institutions. This compilation was necessary for my research, albeit time-consuming, as no institution holds a complete run of these catalogues, and the papers of the AWS were not fully accessible at that time.7 Because the earliest catalogues were not indexed, I made my own handwritten ones. (Those were the days before the internet, friends!) Now, with the resources of the web, it seemed like the right time to finally create for others the indexed and searchable library of catalogues that I had so coveted in the 1970s (fig. 3). Full scans were necessary to capture the linecut (and, later, photoengraved) illustrations that were first included in 1877 and track the increasing sophistication and lavishness of the catalogue design, which set the bar for American exhibition catalogues in the 1880s (figs. 4, 5). Kindly librarians at the Frick Art Reference Library, New York; the Thomas J. Watson Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Winterthur Library, Delaware, helped supply scans. These were loaded into the Internet Archive, with metadata added by Barra American Art fellows. The collection benefits from the bells and whistles that come with the Internet Archive’s ongoing improvements to their online BookReader, which now lets users display the book in multiple ways, search full text, download to an e-book reader, and much more. Loaded on the Internet Archive, the scans can be found by scholars searching from all quarters, not just with links from the PMA website. Most of these scans are searchable (though not always reliably), and scholars will find their research enormously sped up by the analytical chart (tracking dates, location, number of objects and exhibitors, etc.) and cumulative index of artists exhibiting in all the exhibitions from 1867 to 1922, compiled by the indefatigable Barra fellow Torbert.

The first iteration of the website was launched in 2018, a year after the close of the exhibition, as a satellite to the main PMA site. Along with the bibliography, catalogue scans, and indices, this initial version included scans of the printed bibliography and other appendices in the book, such as the membership roster of the AWS and its parent club, the short-lived New York Water Color Society (1850–55); a chronology of the watercolor movement; and an essay by conservator Rebecca Pollak titled “Flash in the Pan: A History of Manufacturing Watercolor Pigments in America.” New to online scholars was an astoundingly useful list of late nineteenth-century American periodicals available on the internet, compiled by Krattenmaker as part of her editing labor, and a link to the important Descriptive Terminology for Works of Art on Paper by PMA conservators Nancy Ash, Scott Homolka, and Stephanie Lussier, with Rebecca Pollak and Eliza Spaulding, edited by Renée Wolcott.8 All scholars can be grateful for the colossal efforts of this team to standardize the descriptive vocabulary in the field. If you need help sorting chalk, pastel, sanguine, and crayon, this is your Bible.

The initial site was designed for expansion and revision, and two years later the second edition appeared, following the launch of the PMA library’s new LibGuide platform, which gathered in the satellite watercolor research portal among its many research tools.9 At the time of this transfer, we added several new sections. The first was for the New York Water Color Club, the upstart rival to the AWS that formed in 1890 and eventually merged with the older society in the 1920s. Posting a parallel set of exhibition catalogue scans up to 1922 (with thanks to the staff at the Boston Public Library, the Frick Art Reference Library, and the Thomas J. Watson Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), we added an index of artists and an analytical chart of the exhibitions, both compiled by diligent Barra fellow Gustin.

Thanks to librarians at the William Morris Hunt Memorial Library at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, we added similar materials from the all-male Boston Water Color Society (with catalogue scans from 1885, its founding year, to 1921, with some gaps) and its competitor, which welcomed both men and women artists, the Boston Water Color Club (with scans from its first catalogue in 1887 to its merger with its rival in 1914, also with some gaps. If you find the missing catalogues from Boston, please let us know!). Finding aids to this new run of catalogues were compiled by the dedicated Torbert from afar, in her new curatorial job at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Turning to Philadelphia, we gathered catalogues from the Philadelphia Water Color Club (from its first annual in 1901 to 1922) and its sister organization, the Pennsylvania Society of Miniature Painters (with catalogues from 1906 to 1922, hoping that the missing early catalogues from 1902 to 1905 will someday surface), thanks to Hoang Trang, archivist at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Gustin again stepped up to help gather these scans and prepare an analytical chart and roster of exhibitors.

This library of searchable scans, together with the discovery tools, offers a wealth of information about the activity of hundreds of artists in this period, perhaps allowing the identification of original titles and dates of works that have survived into the present. It also invites a study of the popularity of all works on paper from this period, as most of these clubs and societies exhibited prints and drawings of all kinds, including wood engravings, etchings, monotypes, crayons, charcoals, and pastels.10

The proliferation of new watercolor societies in many American cities after 1880 gave opportunities to a wave of emerging women artists who turned a traditionally ladylike, amateur medium into a profession. As the aesthetic movement gained speed in the 1870s, women turned watercolor skills learned at home or at school into employment in the decorative arts (e.g., painting on china, coloring prints, and designing stained glass, textiles, and wallpaper), generally under the supervision of men such as John La Farge and Louis C. Tiffany, both expert watercolorists.11 The arrival of the AWS brought a new exhibition forum that, at the outset, liberally welcomed artists from all corners. Many emerging women painters, hoping to transition from commercial or applied art (typically uncredited) to professional fine art careers, found a place in the earliest watercolor exhibitions. However, as the annuals became more popular and profitable around 1880, the crush of competition inspired selective procedures that protected the society’s mostly male membership at the expense of women, amateurs, and outsiders. Dismayed, the women organized new venues. Three of the four new clubs added to the website in 2019 were driven by women artists seeking additional, local exhibition opportunities. I had tracked the participation of women in the AWS exhibitions, confronting the problem of many exhibitors of indeterminate gender, identified only by initials. These masked names, making up a sizeable group in any annual, made the determination of the actual percentage of women artists in the show difficult to compute. Back in the 1970s, suspecting that the percentage of women on the list of initialed artists was high, I made an effort to identify as many of these individuals as possible.

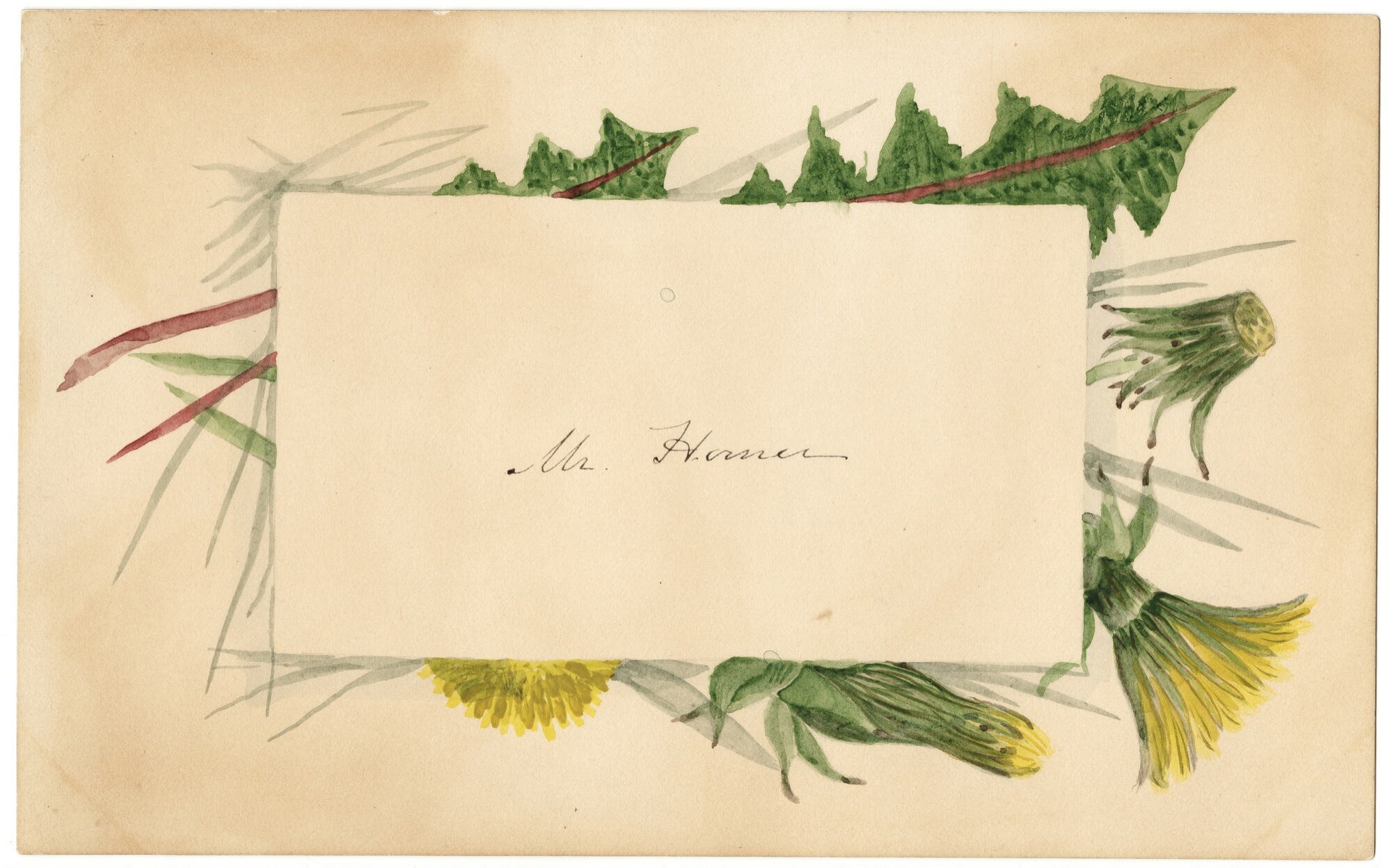

A revelatory case in point was Henrietta Maria Benson Homer, the mother of Winslow Homer. Her watercolors have been known and published for decades; most are botanical studies or bouquets, often vignetted in oval compositions, echoing the decorative designs for needlework and china painting taught to young women in this period. Made for gifts, parlor display, or—like the table cards she ornamented—for special family occasions (fig. 6), these watercolors illustrate the domestic context as well as the painting skills mastered by many women and girls that offered an entrée into the watercolor movement and its professional byways in decoration.12 What was not known was that Henrietta Homer was the first watercolorist in the family to exhibit her work, submitting flower subjects to the spring 1873 exhibition of the Brooklyn Art Association a few weeks after the AWS’s unusually large and stimulating annual exhibition opened at the National Academy of Design in New York. Shown under the name “H. M. Homer” or “Mrs. Homer,” her flower pieces appeared regularly in Brooklyn through 1877. Tellingly, her son took up watercolors with seriousness a few months later, in the summer of 1873, and both mother and son sent work to the AWS annual for the first time early in 1874. Away from her home in Brooklyn and in the more cosmopolitan context of the AWS, Henrietta showed her flower pieces modestly as “H. M. H.” After a second AWS submission in 1875, she retreated to home turf as her son gained prominence.13 Discovering her exhibition career, which evidently set an example for her son, throws new light on her influence on Winslow Homer, just as it offers an example of a “lady amateur” decorator lured into professional exhibition circles by the welcoming spirit of the watercolor movement in the 1870s.

I was able to uncover many unidentified women artists like Henrietta Homer in the course of my research in the 1970s, very often finding the wives and daughters of watercolor painters. The vast new resources of the internet have now been fruitfully applied by the next generation of scholars confronted with the much larger and more female constituencies of the new watercolor societies in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia that we have added to the website. Torbert, having compiled the initial index for the AWS, took up the challenge in her second round of corrections and improvements to the new website in 2019, unveiling dozens of previously unidentified women watercolorists. Her successor as Barra fellow, Gustin, also committed to the stories of women artists at the turn of the twentieth century, likewise reconnected the full names and life dates of many artists working under their initials in Boston and Philadelphia. Our librarian Wratschko has begun to submit these discoveries to the Getty Research Institute’s Union List of Artist Names, such that many women artists previously unknown by art history will now become part of the record. I am happy to say that this recent work necessitates the recalculation of the graph of women participants I produced in American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent.14 The general contours will not change, showing the liberal admission of women in the 1860s and 1870s, their suppression as the watercolor movement reached a peak of popularity between 1878 and 1883, and their rising numbers after 1884 as men splintered off into new clubs and media. However, the number of women artists and their percentage of the total will rise, as dozens of new names emerge for further study.

The study of women artists, who participated in the watercolor societies in much higher numbers than in organizations like the National Academy of Design or the Society of American Artists, may be only one of many topics encouraged by this new research portal.15 The website is built for improvement and expansion, and I welcome suggestions for additional resources. If you are interested in the exhibitions and catalogues—or know about unpublished troves of materials—from other watercolor or graphic arts societies in this period, I welcome ideas for our next edition of the website. In a larger frame, this resource also offers a model for sharing the background research that is often too detailed, wide-ranging, and extraneous to be published in a conventional format, as well as too inaccessible in museum archives or scholars’ homes for general use. It is my hope that such primary material will be shared and analyzed by others, either fellow art historians or perhaps scholars with very different goals, contributing to hitherto unimagined interdisciplinary projects made possible by the burgeoning universe of the digital humanities.

Cite this article: Kathleen A. Foster, “A Research Portal for American Watercolors, Prints, and Drawings 1850–1925: A Source for Obscure Catalogues, Artists’ Societies, and Women Artists,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11677.

PDF: Foster, A Research Portal for American Watercolors

Notes

- Kathleen A. Foster, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, with Yale University Press, 2017). Currently out of print, this book is slated for digital publication in 2021 through the Yale Press subscription-based Art & Architecture ePortal (https://www.aaeportal.com/home). ↵

- My study began as I assisted Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. in his landmark exhibition catalogue, American Master Drawings and Watercolors: A History of Works on Paper from Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Harper and Row, 1976), a survey that remains a good introduction to the longer story of American watercolor and its bibliography. My doctoral thesis, “Makers of the American Watercolor Movement, 1860–1890” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1982), fed a number of important collection catalogues by the Worcester Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others; I reviewed the literature in “Writing the History of American Watercolors and Drawings,” in American Art in the Princeton University Art Museum, vol. 1, Drawings and Watercolors, ed. John Wilmerding (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum, 2004), 49–60. A more recent bibliography for American watercolors, citing these collection catalogues and the important contributions of conservators to the scholarship, is included in American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, 467–74, reproduced as a PDF on the research website: https://philamuseum.libguides.com/AmericanWatercolors. ↵

- Christopher D. M. Atkins, Carl Brandon Strehlke, Jennifer A. Thompson, and Mark S. Tucker, The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2018), https://philamuseum.org/publications/0-2-jgj.html. ↵

- Foster, “Makers of the American Watercolor Movement.” ↵

- I developed chapters from this thesis in “The Pre-Raphaelite Medium: Ruskin, Turner, and American Watercolor,” in The New Path: Ruskin and the American Pre-Raphaelites, ed. Linda S. Ferber and William H. Gerdts (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum, 1985), 79–107; “John La Farge and the American Watercolor Movement: Art for the Decorative Age,” in Henry Adams et al., John La Farge (New York: Abbeville, 1987), 123–59; “Watercolor: Lessons from France and Spain,” in Kathleen A. Foster and Mark Bockrath, Thomas Eakins Rediscovered: Charles Bregler’s Thomas Eakins Collection at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, with Yale University Press, 1997), 81–97; and Shipwrecked! Winslow Homer and “The Life Line” (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, with Yale University Press, 2012). ↵

- The book and the exhibition chose 1925, the year of Sargent’s death, to bracket the period of study. The logical turning point for the catalogue series, however, became 1922, as that year the American Watercolor Society merged its annual exhibition with that of the New York Water Color Club and expanded its membership to include many women. ↵

- The early minutes (but no catalogues) of the American Watercolor Society are available on microfilm from the Archives of American Art. The society maintains a series of catalogues that were inaccessible until recently. ↵

- Nancy Ash, Scott Homolka, and Stephanie Lussier, with Rebecca Pollak and Eliza Spaulding, Descriptive Terminology for Works on Paper, ed. Renée Wolcott (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2014), https://philamuseum.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=50393783. ↵

- A librarian’s review of the new version of the website and its architecture can be read in ARLIS/NA’s multimedia and technology review: Carol Ng-He, review of American Watercolors research portal, Philadelphia Museum of Art, April 2020, Art Libraries Society of North America website, https://arlisna.org/publications/multimedia-technology-reviews/2029-american-watercolors. ↵

- Unfortunately, many of the catalogues describe medium sporadically, although often the non-watercolors are exhibited together. In the early years at the AWS, a “black and white” room contained prints and drawings of all sorts. The exclusion of this non-watercolor material from the AWS exhibitions follows the creation of alternate clubs and annuals, such as the New York Etching Club or the Salmagundi Club (for illustrators). This gradual purification of the AWS was then countered by the eclectic, omnibus exhibitions of the next generation at the New York Water Color Club and the Philadelphia Water Color Club. ↵

- I discuss the place of women in the watercolor movement in “Art for a Decorative Age,” in American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, 155–81, and describe the formation of the new societies in “Illustration and Decoration in the Gilded Age,” 257–93. Much bibliography on the subject of women artists in this period is cited in the notes to these two chapters, but of particular interest for the study of women’s employment in the art world during the aesthetic movement are the following works: April F. Masten, Art Work: Women Artists and Democracy in Mid-Nineteenth-Century New York (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008); Kirsten Swinth, Painting Professionals: Women Artists and the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001); Erica E. Hirshler, A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870–1940 (Boston: MFA Publications, 2001); Amelia Peck and Carol Irish, Candace Wheeler: The Art and Enterprise of American Design, 1875–1900 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001); and Martin Eidelberg, Nina Gray, and Margaret K. Hofer, A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls (New York: New-York Historical Society, 2007). ↵

- On Henrietta Homer and her watercolors, see Foster, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, 23, 178–79. ↵

- Foster, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, 427n97. ↵

- Foster, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, 291. ↵

- Some projects have already benefited from these resources. I was able to draw attention to this material to enlarge or refine the record of work by Alice Schille compiled by Tara R. Keny in In a New Light: Alice Schille and the American Watercolor Movement (Columbus, OH: Columbus Museum of Art, 2019). Likewise, I pointed Eve Kahn to the website for help reconstructing the career of Alethea Hill Platt, and it has helped Andrea West in researching the biography of the watercolorist Susan Bradley. ↵

About the Author(s): Kathleen A. Foster is the Robert L. McNeil, Jr., Senior Curator of American Art and Director, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art