Amateur Status? George W. Bush as Contemporary Artist

In 2013, a hacker published private photographs online of the amateur paintings of former President George W. Bush. They drew immediate attention, online and in the mainstream media. After expressing surprise that Bush had taken up painting, art critics, culture writers, and the general public analyzed the subject matter of the paintings and evaluated their quality. In fact, Bush’s early paintings provoked a level of public interest that very few contemporary artists manage to achieve. In the years since, Bush has not only continued to paint; his painting has become a public relations platform and a key aspect of his public image. The canny instrumentalization of his painting raises a significant challenge to conventional assumptions regarding the nature and purpose of amateur art making. It also raises important questions about the relationship of amateur art to the conceptual concerns and practices that have long dominated contemporary art, particularly the recent turn to socially engaged art practices.

I want to begin with a simple acknowledgment—it is probable that regardless of how proficient an artist George W. Bush is or becomes, he will always be considered an amateur artist, simply because his primary public identity as a president of the United States is so dominant. A defining feature of amateur artists is that they lack a public identity as artists. Their engagement in art making is generally private and secondary to a primary identity. In most cases, when their art is publicly recognized they lose the qualification of amateur and become simply artists. Henri Rousseau and Grandma Moses are prominent examples, although their recognition occurred late in life, and their previous respective identities as customs inspector and homemaker remained part of their identities as modern artists. Paul Gauguin made the transition from Sunday painter to artist so successfully that his early amateur status largely disappeared from public awareness.

All three of these examples belong to the era of modern art, when original self-expression based on innate talent was highly prized, and mastery of the techniques of naturalistic representation was considered irrelevant to significant artistic achievement. In earlier periods, the distinction between amateur and professional artist was much more easily made and maintained on the basis of training and employment. With the advent of modern art and the exaltation of self-expression, originality, rebellion, and a corresponding disdain for mere skill, it became far more difficult to distinguish the amateur from the professional artist. Today, many people successfully claim to be artists, and that identity can have nothing to do with training or remunerative employment. Amateur artists likewise identify themselves as amateurs. In doing so, they reveal the modesty of their ambition and their frequent perception of themselves as having failed to achieve the status of a “true” artist due to a lack of training, ability, dedication, or accomplishment. Typically, amateur artists make art in their leisure time, usually without concern for public recognition or notable achievement, but their levels of training and ability run the gamut.

A famous amateur artist seems almost a contradiction in terms, but occasionally the amateur art making of people well known for other achievements becomes a matter of public interest. Famous amateur artists are often already famous for their work in another field of creative endeavor, as is the case for Bob Dylan and Dennis Hopper. Their work as visual artists falls into a nebulous area between professional and amateur, with their reputation as successful creative producers in one field often seeming to guarantee artistic ability in others. The situation is different for art made by people such as George W. Bush, who are famous for nonartistic achievements. In the mid-twentieth century, Winston Churchill became the exemplary amateur painter and one of the most famous practitioners of the hobby. His 1948 publication, Painting as a Pastime, describes his pleasure in painting and the modesty of his artistic ambitions. Churchill saw painting as the perfect hobby, an “inexpensive independence, a mobile and perennial pleasure apparatus” that provided “new mental food and exercise . . . an added interest to every common scene, an occupation for every idle hour, an unceasing voyage of entrancing discovery.” For amateurs starting to paint late in life, as he did, Churchill prescribed audacity as a substitute for lack of comprehensive training. “We must not be too ambitious. We cannot aspire to masterpieces. We may content ourselves with a joy ride in a paint-box. And for this Audacity is the only ticket.”1 Following Churchill’s advice, President Eisenhower took up painting, as did countless others in the United States during the amateur painting fad of the 1950s.2 Amateur painting was then widely touted as a form of relaxation and a panacea for the drudgery of modern life and labor, a view of amateur art making that has endured to this day.

The rhetoric supporting amateur art making in the mid-twentieth century adopted and democratized the traditional image of amateur art as a refined upper-class leisure activity. Even more significant, the modern conception of art as liberated self-expression became the foundation for conceiving art making as a democratic activity available to all regardless of training or talent.3 The amateur artist’s activity was not clearly differentiated from that of the professional—if the purpose of art is self-expression, there are no universally accepted objective standards for evaluating the quality of artwork. Furthermore, conceiving the professional artist’s activity as an autonomous act of free self-expression eliminates (at least theoretically) the traditional distinction between the professional artist whose art is made with the goal of public exhibition and sale and the amateur who makes art for private pleasure.4

In the art world of today, the evaluative difficulties posed by expressionist values have largely disappeared with artists’ embrace of Conceptual art, preoccupation with nonart media and activities, and meta-critical engagements with traditional media. Amateur art seems to raise few challenges to these practices. The world of hobby art and Sunday painting, which typically involves outmoded, often naturalistic styles and traditional media, appears distant from the frequently esoteric and academic concerns of museums and magazines dedicated to the promotion of cutting-edge contemporary art; however, this is not always the case. Many professional artists have successfully co-opted amateur practices, both literally and figuratively, by adopting styles and approaches associated with amateur art, by employing amateur artists in the creation of their own work, and even by exhibiting art made by amateurs. In addition, some artists embrace their own amateur status in the media or practices they adopt. This is most notable among artists engaged with social practice art and sociopolitical critique whose artwork often involves them taking on the roles of sociologists, anthropologists, environmental scientists, social workers, and community activists.5 We are living in a heyday of amateurism in which expertise is often denigrated in favor of the more liberated and creative insights of the untrained non-professional.6

Although amateur art and amateurism play important roles in the practices of many recognized contemporary artists, amateur artists continue to be associated with conceptual naivete and limited technical abilities. The amateur artist is typically a private individual whose art is known only by a small circle and is easily subject to generalization and stereotype. The Sunday painter of landscapes and family portraits, the amateur photographer capturing the mystery and beauty of the world, and the retiree finding new interest, challenges, and fulfillment in art classes are pervasive and longstanding clichés that reflect a reality evident in exhibitions of local art associations, Etsy, and countless amateur artists’ webpages and Instagram feeds. Nevertheless, despite the banality of much amateur art practice and the shift from the modernist model of art as a form of direct self-expression to more intellectual conceptual approaches, the amateur artist still poses challenges to the significance of contemporary artistic production and evaluation. The artwork of George W. Bush is a particularly interesting locus for exploring these challenges because of its public prominence and direct involvement with social issues. Bush’s painting and its presentation demonstrate how difficult it can be to determine the difference between the canny critical interventions of a professional artist and those of an amateur. In an era when mastery of technical skill is no longer a necessary attribute of the professional artist, and when even an artist’s critical and conceptual understanding are less important than the potential of the work for critical interpretation by others, defining the distinction between the artwork of a professional artist and that of an amateur can be extremely problematic.

Bush began painting after he retired, inspired by Churchill’s publication, Painting as a Pastime, which outlines reasons to paint that would have appealed to him. First, Churchill specifically recommended the cultivation of a hobby to public figures as a means for alleviating the “worry and mental overstrain by persons who, over prolonged periods, have to bear exceptional responsibilities.” Churchill also described painting as a serious hobby that provides discipline and purpose, especially for those “unfortunate people who can command everything they want” and are thereby subject to boredom resulting from the too-easy satiation of their desires. In addition, Churchill noted that painting does not require the physical exertion of sports: it “keeps pace even with feeble steps, and holds her canvas as screen between us and . . . the surly advance of Decrepitude.”7 Churchill’s recommendations, based on his personal experience as a former British prime minister, seem to speak directly to Bush’s situation as a former United States president, who was a very wealthy man in his sixties long dedicated to athletic pursuits.

Previously indifferent to art (as Churchill claimed to have been as well), Bush discovered a new focus for his energies in painting and devoted himself to its study and practice. His technical ability was typical of a beginner, indicating neither remarkable aptitude nor a discouraging degree of incompetence. With instruction and diligent practice, his painting technique improved. After the hacker exposed them online, Bush’s paintings attracted much public interest in national newspapers and magazines. Acceding to this interest, Bush has presented his paintings in two substantial exhibitions at his presidential center in Dallas (in 2014 and 2017).8 The second one was accompanied by an extensive illustrated catalogue, Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors.9

From the first paintings revealed online, two of which were unequivocally private and idiosyncratic, to the subsequent paintings of world leaders and wounded veterans, Bush has developed an artistic persona that embraces his identity as a former president. To an extent he follows in the footsteps of other world-famous amateurs, most notably Churchill but also HRH Prince Charles, Prince of Wales, who, like Bush, has used his painting hobby to raise funds for his charitable organizations through exhibitions and publications.10 Unlike these predecessors, however, Bush’s efforts as an amateur painter have distinct parallels to the tendencies and strategies of recent contemporary art. Ultimately, what most distinguishes his art from that of established contemporary artists may be his own well-established identity as a former president and a nonartist, and the direct relationship of his painting to that identity, instead of a lack of the skill and conceptual acumen possessed by successful contemporary artists.

Bush’s painting, unlike the naturalistic plein air landscapes of Winston Churchill and watercolors of royal properties and picturesque scenery of Prince Charles, is not obviously conservative or retrograde in approach. He works largely from photographs, a common practice among contemporary artists, who, like Bush, frequently lack significant skills in naturalistic representation. Bush’s painting is also in sync with an art world that prizes political involvement and often exhibits disdain for technical virtuosity. Although his paintings are typically not exhibited in art galleries, indicating that they are not intended to be evaluated as art, recent developments in contemporary art have made the distinction between art and nonart exhibition spaces less central to defining what is art and what is not.11 Contemporary artists frequently exhibit work outside galleries and established art world venues, and working with the nonart world is often central to the significance of their art. Divisions between art and nonart, particularly in the context of social and political engagement and activities, have become increasingly irrelevant as more and more artists adopt nonart activities as art and even present nonartists’ work and activities as art. This populist approach to art making has limits, however, as illustrated by a tendency to value the critical intelligence of artists over that of nonartists. Critical reception of Bush’s painting is a prime example of this bias.12

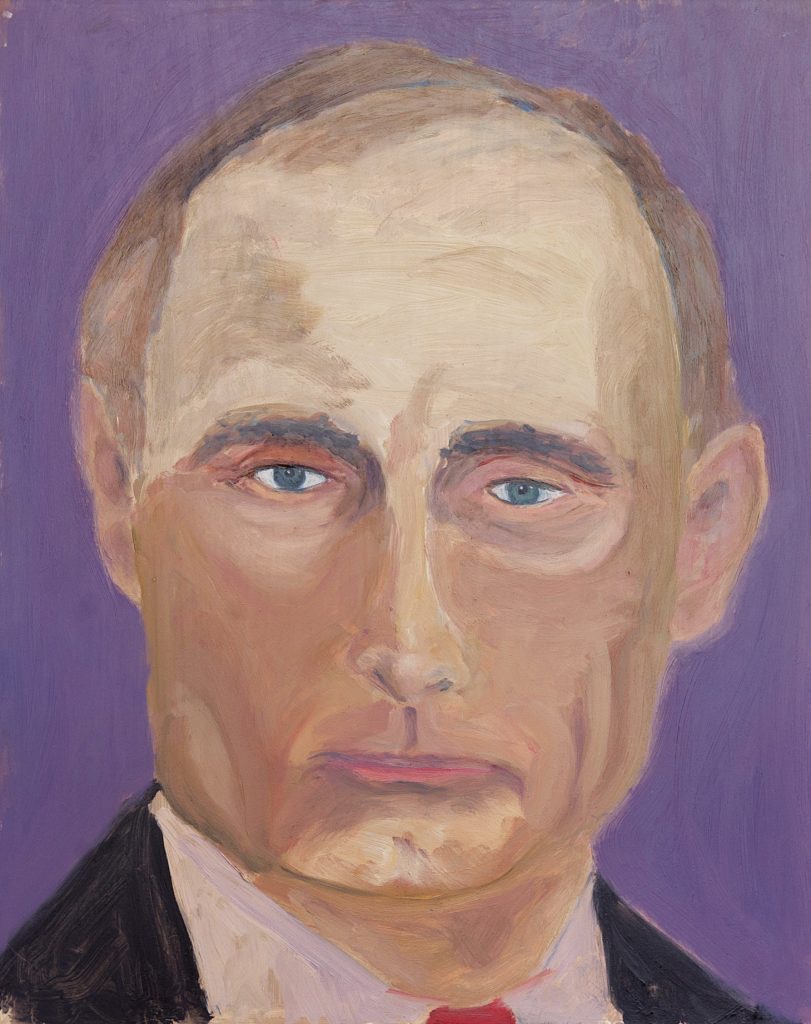

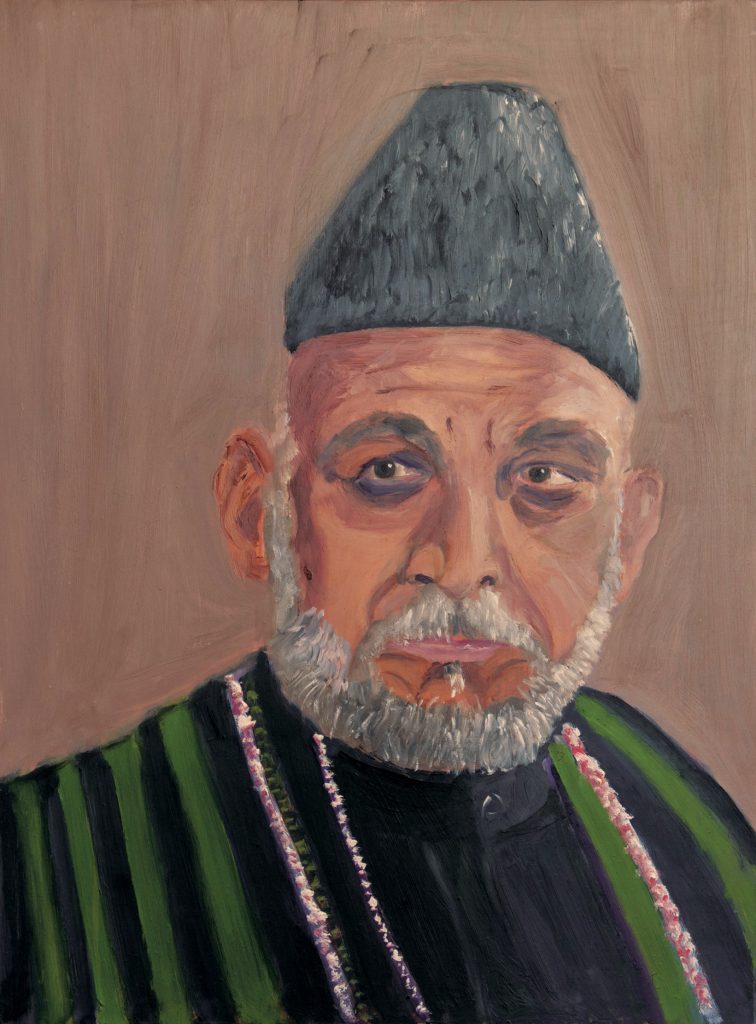

Imagine for a moment the critical response if the 2014 Art of Leadership exhibition of paintings, memorabilia, and photographs of world leaders at the Bush Presidential Center had been displayed, unchanged, as the work of a young contemporary artist (figs. 1, 2). The installation would likely have been seen as a critical investigation of the mediatizing of politics and world leadership, and the awkward photography-based portraits as a commentary on the flatness and vacuousness of the people who govern the world (figs. 3, 4). The significant artifacts on display would be exposed as mere flotsam and jetsam rendered meaningful by their context in the symbolic gift economy of rulers of nations. In fact, it is not even necessary to imagine Bush’s paintings as having been created by someone else to interpret them plausibly in terms of critical issues and approaches often employed by contemporary artists. A hypothetical critic might explain their photographic flatness as Bush’s canny commentary on his own experience:

The world depicted in Bush’s paintings is one in which everything is already an image or a sign. The paintings of world leaders have no visible signatures, but Bush signed many of his early non-public paintings “43,” suggesting that he sees himself as a number, one of a sequence, someone caught in the ramifications of history, a moment in the story of a nation and its role in the world. Anyone seeking to understand the paintings as disclosing the inner identity of the man must reconsider. The man they might reveal remains hidden; he is a place holder, a figure of the digital age.

Of course, the artist’s intentions cannot be completely ignored, and a plausible objection to this interpretation is that Bush’s paintings of world leaders were not intended to be metacritical commentaries. It would nevertheless be a mistake to regard them simply as naive exercises in portrait painting. Intention is always a complex problem for critical interpretation, regardless of the artist’s status, and Bush’s intentions are complicated by his own statements, which sometimes rival those of Andy Warhol in their evasive refusal to take full responsibility for his work. In this, he follows other prominent amateurs. Winston Churchill and Prince Charles also emphasized their lack of professional skills and the time and dedication necessary for significant artistic achievement. More interesting than the modest disclaimers, however, are Bush’s disavowals of conceptual credit for the subjects of his paintings. According to Bush, his painting teachers and professional artist mentors have been largely responsible for what he paints, and they prompted the subjects for both of his portrait series. It was Roger Winter’s idea to paint world leaders, and Sedrick Huckaby suggested he paint unfamous people he knew, which Bush claimed was the origin of his paintings of wounded veterans.13 Giving credit to others for the subjects of his painting projects can be seen as both acknowledgment of his mentors’ assistance and an evasion of personal responsibility. The latter distances him from authorship and any claim to originality. This can be interpreted as another instance of modesty, but it can also be understood as a statement about the nature of his art as a strategically considered product that signifies individual authorship without a foundation in personal engagement. Although he initially signed his paintings with the economical and enigmatic “43,” his public portraits have no visible signatures at all, an intriguing gesture of self-effacement with multiple significations.

In an interview about his portraits of world leaders, Bush acknowledged that his signature was worth much more than his painting.14 Withholding his signature suggests he wants his paintings to be valued on their own terms and also that a signature is unnecessary, given that context makes their authorship obvious and that the paintings will not be put on the market. In addition to market value, the concepts of authorship and anonymity evoke the “death of the author” discourse theorized by Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault in the 1960s and its enormous influence on Conceptual art in subsequent decades. The elevation of audience interpretation over authorial intention associated with this discourse can be seen as offering an important opening for amateur artists whose work will, at least theoretically, be evaluated without reference to the reputation of its creator. Of course, Bush is hardly an unknown author, and his authorship, as well as his authority, raise complex issues that most amateur artists do not face.Like Warhol, George W. Bush is a skillful manipulator of his public persona as an artist. He retrospectively claimed that the two paintings discovered and published online in 2013, which show him in the bathroom, were made to “shock” his painting teacher, Gail Norfleet.15 Surely this is a disingenuous and playful response to the extensive commentary the paintings received after they were made public instead of an accurate account of their genesis. They are unlikely to have shocked Norfleet, who probably gave him a standard assignment for beginners to paint a self-portrait using a prompt such as “how you see yourself.” The results are both humorously self-deprecating and revealing, and the widespread interest the paintings raised was deserved. They are unusual in conception and subject matter: one depicts the painter’s view of his knees and feet rising above the water in the bathtub.16 The other shows Bush from the back in the shower; his face floats detached as a reflection in a small round mirror above the back of his head, placing the viewer in a peculiar voyeuristic relation to the image. Jonathan Alter described the paintings as “embarrassing if psychologically compelling self-portraits,” while Jerry Saltz rhapsodized at length and exhorted the Whitney Museum to buy them.17

The paintings stand out not only in their idiosyncratic conception but in the way they probe the nature of representation and identity; these are self-representations of a man whose identity is a highly manufactured image. Where does such a man really see himself? The bathroom is arguably the only place where the President may have a few minutes of solitude and privacy. It is also where he directly confronts his unmediated corporeal self. In depicting himself in the shower, revealing nothing but his back and his face peering out detached and disembodied in a round frame, Bush created a striking visual commentary on the alienation of being a relentlessly scrutinized public figure. Many comments have been made about the paintings’ depiction of the act of washing, suggesting guilt, purification, and baptism. They also depict physical entrapment. The body is elided and truncated, caught in the grid of the shower tiles, imprisoned by the narrow tub and its black surround. Bush’s dismissal of the paintings as a puerile attempt to shock his teacher rejected serious consideration of them, but they demonstrate Bush’s capacity for sophisticated pictorial intelligence. They also seem to confirm the modern belief that paintings, particularly paintings made by the artistically untrained, are self-expressive and can reveal deep, nonverbal truths about the artist’s experience.18

None of the other early paintings by Bush that have been made public suggest unfamiliar depths behind his established image as just a regular guy. Following Norfleet’s instructions, he initially painted what he liked, and dogs and the Texas countryside seem to have predominated. A reference to this predilection is apparent in the printed backdrop used in 2017 for “The Art of Painting: A Conversation with President Bush’s Art Instructors” at the Bush Presidential Center, which reproduced another self-portrait of Bush seen from behind (fig. 5). In this image, Bush is depicted fully clothed, working at his easel on a painting of a spaniel who stares out of the canvas over Bush’s shoulder at the viewer.19 Here, at enormous scale, is proof that Bush’s painting is merely the dedicated pastime of a man who likes dogs.

Despite their banal subject matter, soon after they were revealed, Bush’s early paintings began to redeem his public image. Prominent critics and writers as well as many members of the general public admitted to liking Bush the painter even though they disliked him as president.20 People remarked that they were not only surprised he had taken up painting after witnessing so many years of macho swagger; they were also impressed by his diligence and dedication to his newfound passion.21 This positive reception created an opportunity that Bush was quick to seize.22 Although Bush likely expected his painting to be a private hobby inside what he called the post-presidential bubble, after it attracted public interest he directed it to promotional ends and had his first public exhibition a year later at his presidential center in Dallas.23

The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy was publicized as providing “an insider’s view into President Bush’s unique relationships with other world leaders.”24 The exhibition not only took advantage of public interest in Bush’s painting to draw people to visit his presidential center and learn about his presidency, it also built on implicit assumptions that painting is an act of self-expression to display the former president’s personal connections with other world leaders.25 The end result was ironic; there was no evidence of intimacy in the paintings. They seem to have been based on standard publicity photographs, and one reporter noted that they were often the first images to appear in Google searches.26 Despite the promises in the publicity copy and Bush’s own statement that the portraits were made possible by his intimate relationships with world leaders, the paintings were images of surfaces. The visible brushstrokes signified emotion, but what New York Times art critic Roberta Smith described as “awkward images enlivened by distortions and slightly ham-handed brushwork” revealed no more hidden depths than the photographs Bush copied.27 Several critics stressed the superficiality of the paintings, and Jason Farago described them in The Guardian as “counterfeit studio banality. Their vacancy, their stubborn refusal to offer anything beyond the most basic signal of a famous person’s identity, is precisely what Bush will have wanted. . . . nothing is at stake here. It is futile to gaze at these paintings and discover anything of importance about Bush’s foreign policy, or even much about Bush’s post-retirement life.”28

Bush’s painting hobby has become an aspect of his identity as a public figure. It joins brush clearing, biking, jogging, golf, a fondness for puns, and the public use of silly nicknames to address prominent individuals as one more way to present the former president (the scion of a wealthy, socially prominent family and son of a president) as approachable, a man with whom ordinary people can find personal connection. Painting added a hitherto unrevealed soupçon of sensitivity to his image; he is now the retired man “finding his inner Rembrandt” and developing his neglected creative potential.

This view is naive. Bush’s paintings are an integral part of a personality inescapably immersed in its own portrayal, the products of a fully mediatized being. To regard them as the results of innocent self-expression is no more (or less) viable than to regard the paintings of any number of critically acclaimed contemporary artists as such. Bush’s paintings are, in fact, an incisive digital-age critique of painting. They are visual signs of depth, of personal knowledge, of meaning. They give the public a sense of intimacy with a famous person without in fact revealing anything at all. Bush is an amateur painter, but he is an expert in public relations, image making, and the media. His limited knowledge of painting technique cannot be assumed equivalent to a lack of pictorial sophistication.

Roberta Smith compared Bush’s portraits of world leaders to the work of Luc Tuymans, who has produced photography-based, amateur-style paintings of former Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice and the first prime minister of the Republic of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba.29 Tuymans’s paintings are usually positioned in terms of critical conceptualism, and the artist is credited with a high degree of intellectual and political involvement. His work is considered a critique of our image-saturated, media-driven culture and its inability to convey the depth and significance of historical figures and events.30 Bush’s portraits of world leaders, while less interesting in terms of composition and painting technique, perform a similar critique, albeit one that was unlikely to have been consciously intended. But artistic intention is notoriously slippery, particularly in relation to sophisticated critical interpretations. Cindy Sherman, to take a prominent example, has admitted to not fully understanding influential theoretical interpretations of her work. In her case, and that of many successful artists, critics discount the artist’s claims of ignorance or denial of specific intentions. What matters is less the artist’s conscious intention than the plausibility and fecundity of the interpretation, and that is surely relevant to understanding Bush’s painting and its strategically designed presentations.

In intention and effect, Bush’s paintings are more similar to Elizabeth Peyton’s celebrity portraits than they are to Tuymans’s paintings of political leaders. Peyton became famous for faux teenage fan art, amateur-style paintings reproducing photographs of pop music icons and her art world friends.31 She has also painted images of numerous famous historical and contemporary figures, including Napoleon; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and her son, John; Princes William and Harry; and the Obamas. Her paintings are commonly described as updates of Andy Warhol’s celebrity portraits, but in contrast to Warhol’s notorious emotional detachment, Peyton claims that her paintings are the product of intense feeling for and involvement with her subjects. This emotional investment is typically stressed by admiring critics, while at the same time Peyton’s portraits are considered to be knowing postmodern critiques of media imagery. These theoretically irreconcilable views situate her as someone caught up in the complexities and contradictions of intense relationships with people who are public figures, people she may not know at all. What does it mean to have feelings for famous people, for people who are images? Affect and image become clichés; there is no profound feeling to portray. Bush’s portraits of world leaders, exhibited as evidence of his “unique relationships,” convey a similar message in the context of politics.

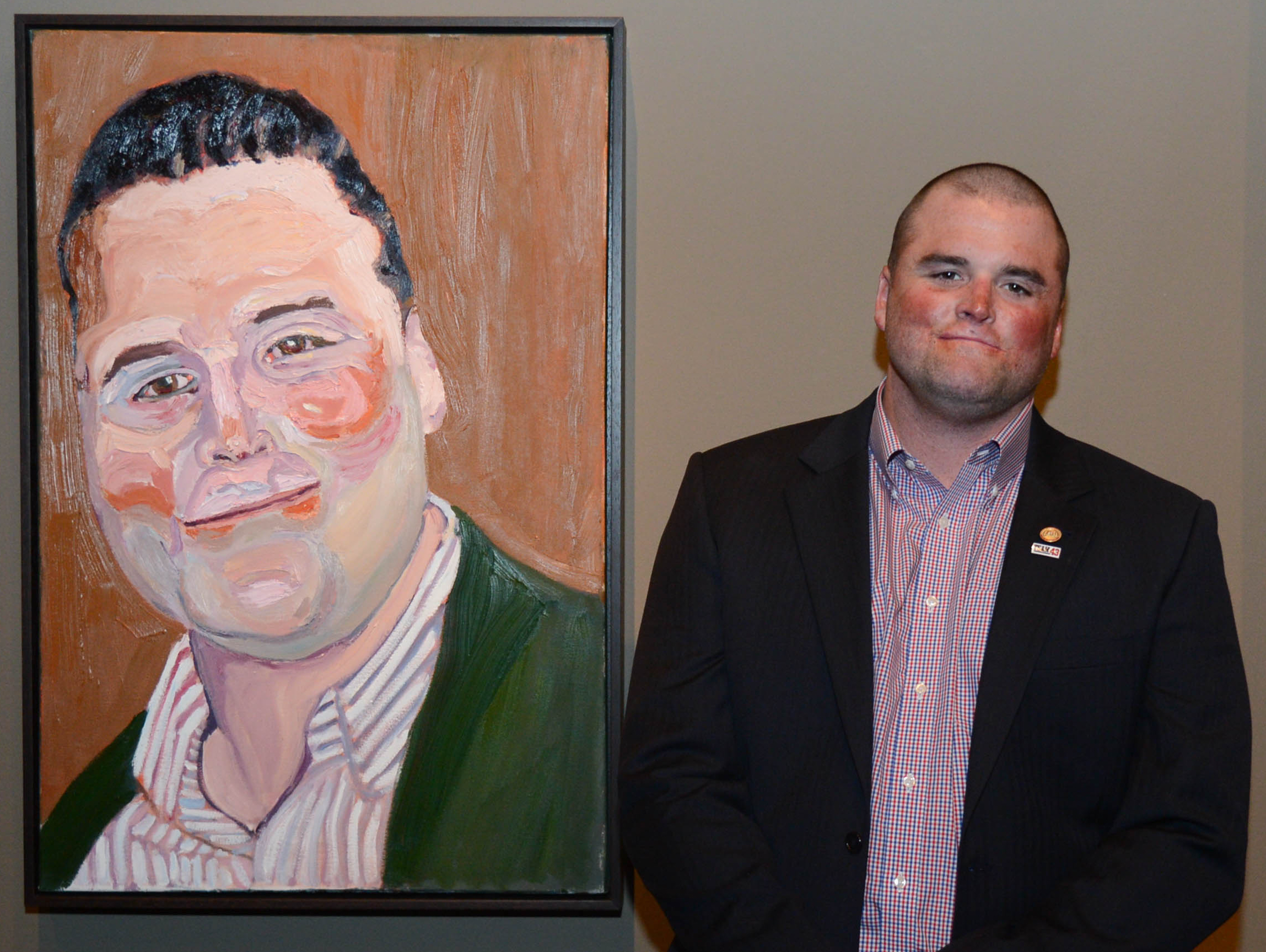

Bush’s portraits of world leaders present the superficiality of world leaders and their relationships, but the interpretive stakes are notably different for the much larger and extensively promoted portraits of disabled veterans, the “wounded warriors” of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars (figs. 6–9).32 These are also portraits of people that Bush claims to know personally, and they too were painted from photographs. Like The Art of Leadership exhibition, Portraits of Courage presents Bush’s painting in the larger context of politics and social action. Bush states in his introduction to the catalogue that he “painted these men and women as a way to honor their service to the country and to show my respect for their sacrifice and courage. . . . each painting was done with a lot of care and respect. This is more than an art book. This is a book about men and women who have been tremendous national assets in the Armed Forces. . . . I intend to salute and support them for the rest of my life.”33 All proceeds from the sale of the catalogue support the Military Service Initiative of the Bush Institute. Visiting the exhibition and buying the catalogue can be construed as support for veterans—and perhaps also implicitly for Bush’s policies, which led to the military interventions that created these wounds. Critical responses to the exhibition have repeatedly noted discomfort with viewing paintings by the man whom many consider ultimately responsible for the wounded individuals they depict.34

As noted above, Bush’s initial idea for the series was prompted by the suggestion of painter Sedrick Huckaby to paint unfamous people he knew. The political motivation of the project is obvious: it demonstrates Bush’s dedication to veterans, his personal involvement with them, and his sense of responsibility for their individual journeys. The final goal of a substantial public exhibition and catalogue to raise money for his charity gave form and purpose to Bush’s regular practice of painting. Beyond their basic conception and motivations, the Portraits of Courage paintings prompt consideration of interesting issues regarding representation and reception. Bush’s catalogue introduction states that he studied the photographs, and as he painted them he “thought about their backgrounds, their time in the military, and the issues they dealt with as a result of combat.”35 That is, of course, what the exhibition and catalogue are designed to do for viewers. Bush displays the results of his close attention to the wounded veterans in an effort to elicit awareness of both his subject and his own attention. Viewers witness the former Commander in Chief’s tribute and are expected to join him. The paintings are therefore both witnesses and performances. They represent time spent and attention given. The uneven quality of the paintings, their various awkwardnesses, can be read not simply as indications of painterly ineptitude, but as the signs of the difficulty of the task, the enormous gulf between the painter and his subjects.

The former President is a man, a symbol, and an image. That layered identity did not cease with the end of his presidency, and his involvement with the veterans of the military conflicts initiated during his years in office indicates his recognition that his image is still important. The paintings turn being into performance. Bush has fashioned a new image of himself as a maker of images. The fact that the paintings he creates are based on photographs, perhaps enhanced by meeting with the subjects, and a written account of the biography of the individual being portrayed is not just a matter of practical limits. It is representative of how little not only Bush but everyone knows of other people, their experiences, their pain, and their triumphs. Bush’s paintings are representations of representations because that is in the end all that is possible. The effort to know, however, is important. We live in representation, but also in attempts to understand and to make connections. This is also the significance of Bush’s paintings. He knows how important his acknowledgment and his attention are to the wounded veterans he supports. That is his role, and the subtitle of the catalogue, A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors, makes that clear.

The painting style Bush employs, the heavy impasto and closely cropped focus on the head, suggest intense scrutiny and expressive response.36 The focus on the head honors the individual, but it is also a means to isolate the individual from the context of their sacrifice and trauma, as well as debates about the justice and purpose of the war. The viewer stares into the painted eyes, and the effect is surely intended to convey the psychological depths of the individual. Bush once notoriously claimed to have looked into Vladimir Putin’s eyes and seen his soul, and when he began painting, he expressed a desire to discover his inner Rembrandt, the great master of the heavily impastoed, soul-revealing portrait. Nevertheless, despite Bush’s apparent belief that it is possible to see a person’s soul in their eyes, and the evocation of individual personalities in the paintings, they reveal nothing of the trauma endured by these wounded veterans. To represent that would require a Francis Bacon, an Edvard Munch, or a Käthe Kollwitz.37 Bush’s photography-based paintings have a much different goal: to “give viewers a sense of the remarkable character of these men and women . . . to show their determination to recover, lack of self-pity, and desire to continue to serve in new ways.”38 Bush uses casual, sometimes smiling, photographs as the basis for his portraits; they serve as images of health and recovery. This is what Bush, as their former Commander in Chief, needs to do: convey images of support, of hope and wholeness. As a man who has spent much of his life as a representation, he knows the power of images and the ways they create reality. Painting is just another way of using that knowledge. His portraits demonstrate that he, too, sees—he is not just an image, but an image that looks back and affirms the identities of each wounded veteran.

Bush’s publicly exhibited paintings cannot be dismissed as simply conforming to outdated conceptions of painting as self-expression so often associated with amateurism. They are in fact a performance and production mobilized for social effect. Social activist art is typically associated with liberal causes and mobilizing opposition to established interests and controls. The Portraits of Courage exhibition is literally and figuratively backed by powerful conservative institutions, but like much social activist art, its purpose is to draw public attention and assist communities in need of support.

Currently, it is difficult to articulate reliable concrete or theoretical distinctions between the artwork of professional and amateur artists. Even what is usually presumed to be the most important difference—that between the intellectual rigors of conceptual artistic practices and the purportedly naive, retrograde productions of many amateurs— can no longer be taken for granted. Bush is a prominent example of someone whose lack of professional training in a pictorial medium cannot be assumed to indicate a lack of sophisticated understanding of images. Even considered in isolation from their presentation in exhibitions, Bush’s paintings are as interesting as those of many prominent contemporary artists.39 If Bush is granted the intellectual credibility commonly attributed to contemporary artists, his paintings may be readily interpreted as meaningful investigations of our contemporary mediatized culture and its overwhelming effects on politics and society. We live in a world of images where we are all to some degree experts. Today’s amateur artist may not be so naive after all.

Cite this article: Kim Grant, “Amateur Status? George W. Bush as Contemporary Artist,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1687.

PDF: Grant, Amateur Status?

Notes

- Winston Churchill, Painting as a Pastime (New York: McGraw Hill, 1950), available online as Project Gutenberg Canada ebook no. 1373, n.p. ↵

- For detailed discussions of amateur painting in the 1950s, see Karal Ann Marling, As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994) and Kim Grant, “‘Paint and Be Happy’”: The Modern Artist and the Amateur Painter—A Question of Distinction,” Journal of American Culture 34, no. 3 (September 2011): 289–303. ↵

- At the beginning of the amateur painting fad of the 1950s, Alison Mason Kingsbury wrote: “The very direction taken by the present practicing artist was established over a century ago with the Romantic Movement, which liberated art from authority and gave the right to paint to the individual. The subsequent innovators were amateurs in the truest sense. They preferred to discover and to paint what they believed, rather than to sell. Their doctrine of free expression permeates all our aesthetic thought as surely as the doctrines of Jean-Jacques Rousseau permeate our social and political thought.” Alison Mason Kingsbury, “Amateur Standing: Symptoms in Ithaca,” ARTnews 48 (Summer 1949): 10. ↵

- During the amateur art fad of the early 1950s, the primary distinction many critics made between the professional modern artist and the amateur hinged on dedication, not on the quality of the art produced. Professional artists were devoted to what Emily Genauer called “the most agonizing soul-searching effort”; amateurs, by contrast, painted for fun. See Emily Genauer, “Amateurs—Those Who Paint as a Pastime,” Art Digest 24 (January 15, 1950): 13. The critical failure to establish identifiable qualitative differences between the self-expression of amateurs and modern artists’ liberation from artistic training and rules is evident in the pages of ARTnews magazine, where critical promotion of the liberated expression of the New York School artists directly clashed with support for the amateur art movement of the early 1950s. In a remarkable 1953 editorial, the magazine begged amateurs not to prostitute themselves by selling their art in fashionable New York City galleries because it took bread out of the mouths of dedicated professionals. See Albert Frankfurter, “Editorial: Amateur Joy or Professional Agony? ARTnews 51 (February 1953): 15. ↵

- For overviews and discussions of many of the most prominent artists working in the broad area of social practice, see Nato Thompson, Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991–2011 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012); Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); Grant Kester, The One and The Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); Tom Finkelpearl, What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013); Bill Kelley Jr. and Grant Kester, eds., Collective Situations: Readings in Contemporary Latin American Art, 1995–2010 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). ↵

- For an extended exaltation of the amateur at the expense of the “ideologically driven world of professionals” see Andy Merrifield, The Amateur: The Pleasures of Doing What You Love (London: Verso, 2017). ↵

- Churchill, Painting as a Pastime, n.p. ↵

- The Art of Leadership exhibition was held at the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University in Dallas in 2014. It was also on display for one day at the conservative Freedom Conference and Festival in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, in 2017. Portraits of Courage was also first exhibited at the Bush Presidential Center. It then traveled to the Museum of the Southwest, Midland, Texas; Wonders of Wildlife, Springfield, Missouri; the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Texas; the Arizona Heritage Center at Papago Parke in Tempe, Arizona; and, the Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Florida. ↵

- George W. Bush, Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors (New York: Crown Publishers, 2017). The catalogue includes forewords by Laura Bush and General Peter Pace and an introductory essay by George W. Bush, as well as full-page reproductions of the portraits accompanied by text about the person portrayed. ↵

- Former President Jimmy Carter is also an amateur painter and has auctioned off paintings to support his charities, as well as turning them into greeting cards. Some of his paintings were published in a book of reflections in 2015. Carter only started to spend significant time on his painting in his eighties. Jimmy Carter, A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015). His painting hobby has not received as much public attention as Bush’s, and he has not exhibited his paintings as a group. They have, however, sold for impressive sums at charity auctions to benefit the Carter Center. One oil painting of crabapple blossoms sold for $750,000 at auction in 2016. ↵

- Of the various locations in which Bush’s work has been exhibited, the Society of the Four Arts in Palm Beach, Florida, is the only dedicated arts venue. A key indicator that Bush is not seeking to establish a public identity as an artist is that he has no gallery or other form of public relations representation for his art, apart from the Bush Presidential Center in Dallas, Texas. ↵

- Also coloring the critical reception of Bush’s painting is his political conservativism, which is at odds with the generally liberal attitudes of the contemporary art world. ↵

- George W. Bush, “Painting as a Passion: An Introduction,” in Portraits of Courage, 13–14. ↵

- At the conclusion of the video interview Bush and his wife Laura gave to accompany The Art of Leadership, Bush says, with self-deprecating modesty, “I fully understand that the signature is worth more than the painting.” ↵

- Numerous magazines and other websites republished Bush’s hacked self-portraits online, including Vanity Fair and Salon.com: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2013/02/nude-self-portrait-george-w-bush-critique, https://www.salon.com/2013/03/26/no_george_w_bushs_paintings_tell_us_nothing_about_iraq. ↵

- Frida Kahlo’s 1938 painting “What the Water Gave Me” shows a similar view of her body, but her painting also includes many small images of scenes rising from the bathtub water. ↵

- Jonathan Alter, “Bush Nostalgia is Overrated, but His Book of Paintings is Not,” New York Times, April 17, 2017; Jerry Saltz, “George W. Bush is a Good Painter,” Vulture, February 8, 2013, http://www.vulture.com/2013/02/jerry-saltz-george-w-bush-is-a-good-painter.html. ↵

- Jerry Saltz wrote, “These are pictures of someone dissembling without knowing it, unprotected and on display, but split between the promptings of his own inner drives and limited by his abilities. They reflect the pleasures of disinterestedness. A floater. Inert. The images of a man who saw the entire world from the inside but who finds the smallest, most private place in a private home to imagine his universe.” See Saltz, “George W. Bush is a Good Painter.” In a similar but less complimentary vein, Hrag Vartanian wrote, “This is a man who is obviously feeling his mortality. . . . There is almost a melancholy in these images. . . . Once the most powerful man in the world, Bush is now alone, exploring his immediate surroundings in these spurts of introspection.” See Hrag Vartanian, “Do Bush’s Paintings Tell Us Anything About the Former President?” Hyperallergic, February 8, 2013, https://hyperallergic.com/64837/do-bushs-paintings-tell-us-anything-about-the-former-president. Another writer described the shower painting as evidencing “soul searching introspection” and wrote that it depicted Bush “as if contemplating past sins that can never be washed away. . . . His disembodied face appears . . . like a haunting apparition. ‘You can’t hide from yourself,’ the face is saying. ‘You can’t hide from God.’” See Dan Amira, “Overanalyzing George W. Bush’s Painting of Himself Taking a Shower,” Daily Intelligencer, New York Magazine, February 8, 2013, http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/02/george-bush-shower-painting-hack-photo.html. ↵

- The dog is probably a portrait of a family pet; Bush’s parents and his wife have owned spaniels. ↵

- Juli Weiner, “How George Bush Evolved from the Uncoolest Person on the Planet to Hipster Icon,” VF Daily, December 13, 2013, http://www.vanityfair.com/online/daily/2013/12/george-w-bush-cade-foster-hipster-paintings. ↵

- Nick Bryant, “George W. Bush Exhibits his Paintings of World Leaders,” BBC News, April 4, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-26890910; Roberta Smith, “The Faces of Power, From the Portraitist in Chief,” New York Times, April 7, 2014, C1; and Edward Goldman, “W. Reveals Himself as ‘a Decent Amateur’ Artist,” Art Talk on KCRW April 8, 2014, https://www.kcrw.com/news-culture/shows/art-talk/w-reveals-himself-as-a-decent-amateur-artist. ↵

- Bush’s public persona is undoubtedly shaped in large part by public relations professionals who play an important role in using his painting to bring public attention to the Bush Center and to burnish Bush’s presidential image and legacy. The involvement of public relations professionals has direct parallels to contemporary art practice in which dealers, assistants, and curators play key roles. Therefore, I am eliding these contributions and, following standard art-critical practice, I am here considering Bush as the sole conceptual agent of his work and its presentation. ↵

- A month after his paintings were first made public by a hacker, he said he had no plans for an exhibition. See Judy Keen, “George W. Bush: Happy to be Out of the Limelight,” USA TODAY, April 21, 2013, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/04/21/bush-happy-to-be-out-of-the-limelight/2099199. ↵

- “George W. Bush Presidential Center Announces 2014 Special Exhibitions,” George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum website, https://www.georgewbushlibrary.smu.edu/en/News-and-Events/~/link.aspx?_id=5557407558EE4E5BB7019D768FB68191&_z=z, accessed April 4, 2019. ↵

- In an NBC Today Show interview with his daughter Jenna Bush Hager about the exhibition, Bush indicated that the paintings were displayed to lure people to come to the center to be educated about his presidency. George W. Bush “George W. Bush on Dad: ‘I Painted a Gentle Soul,’” interview by Jenna Bush Hager, Today, April 4, 2014, https://www.today.com/video/today/54864022. ↵

- Samantha Grossman, “George W. Bush’s Painting of World Leaders Appear to Be Based on Good Ol’ Google Searches,” Time Newsfeed–Arts, April 9, 2014, http://time.com/55491/george-w-bush-paintings-google-images. ↵

- Smith, “The Faces of Power.” ↵

- Jason Farago, “George W Bush’s Portraits of World Leaders: Art that Tells us Nothing at All,” The Guardian, April 4, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/apr/04/george-bush-portraits-world-leaders. ↵

- Smith, “The Faces of Power.” ↵

- Helen Molesworth and Madeleine Grynsztejn, eds. Luc Tuymans (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Wexner Center for the Arts/D.A.P., 2009). ↵

- Laura Hoptman, ed. Live Forever: Elizabeth Peyton (New York: Phaidon, 2008); and Dodi Kazanjian, Elizabeth Peyton: Here She Comes Now (Cologne, Germany: Walter Koenig, 2013). ↵

- The only paintings by Bush that received permission to be reproduced for this article were those that appear in photographs on the Bush Presidential Center Flickr site, which documents events sponsored by the center. Therefore, it was not possible to get permission to reproduce individual works from the Portraits of Courage series outside the context of an event at the Bush Center. ↵

- Bush, “Painting as a Passion,” 15. ↵

- Peter Schjeldal, “George W. Bush’s Painted Atonements,” New Yorker, March 3, 2017; Joshua David Stein, “George W. Bush’s Talent as a Painter Finds an Ironic Muse: The Combat Veteran,” The Guardian, March 6, 2017; Seph Rodney, “George W. Bush’s Paintings Cannot Redeem Him,” Hyperallergic, March 28, 2017; M. Neelika Jayawardane, “George W. Bush Cannot Hide His Crimes Behind Paintings,” Aljazeera, April 13, 2017; and Melissa Warak, “Warriors and Volunteers: A Review of George W. Bush, Portraits of Courage,” Art Journal Open, July 2, 2018 http://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=9949. ↵

- Bush, “Painting as a Passion,” 14. ↵

- Most of the seventy paintings are closely cropped portraits of individuals, but the exhibition also includes one portrait of a veteran with his wife; six half-length figures, two of which include a child; and seven full-length figures, two of which depict two figures playing golf, and one painting of a veteran dancing with Bush. There are also group portrait murals on green painted panels in which the individual portrait heads were painted from separate photographs. ↵

- Joshua Stein sees the paintings as obsessive in their repetition and asks, “What painter but George W. Bush could be party to one of the most complex relationships between artist and subject in recent history?” This is certainly an aspect of the paintings’ interest, but it concerns their context, not what the paintings themselves express or reveal. See Stein, “George W. Bush’s Talent as a Painter Finds an Ironic Muse.” ↵

- Bush, “Painting as a Passion,” 15. ↵

- Michael Fried famously condemned Minimalism as “merely interesting” compared to the significance and exaltation of true aesthetic achievement. The latter is now widely regarded as an outdated, elitist, even mystifying, goal by many in the art world, where social relevance and inclusivity now outrank pure aesthetic concerns. Contemporary art now largely aspires to be “merely interesting” in Fried’s sense, meaning it prompts viewers to engage in thoughtful contemplation of their own relationship to the artwork and the ideas it suggests. See Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum 5, no. 10 (Summer 1967): 12–23. ↵

About the Author(s): Kim Grant is Professor in the Department of Art at the University of Southern Maine