Archival Assembly: The Black Artists of Oklahoma Project and Art-Historical Infrastructure

PDF: VonGries and Bailey, Archival Assembly

Begun in 2020, the Black Artists of Oklahoma Project is a multiplatform collaborative effort based in the School of Visual Arts at the University of Oklahoma (OU) that celebrates the history of African American and other African diaspora art in Oklahoma through research, exhibitions, publications, and related programming.1 Unable to find a comprehensive resource on the work of Black artists from Oklahoma, we set about redressing that lack by gathering records of the past while also providing currently working artists with opportunities that we are documenting thoroughly. The project is still new, in the process of growing and evolving. We do not yet know what its full scope will be or what shape it will take, but so far, this very sense of openness has been itself a boon, helpful to the project’s purpose. Our intent is to produce an up-to-date, relevant resource that creates access to analog and digital sources and can continue to be modified into the future as we work together with its user communities to build better histories of Black art in Oklahoma.

We developed the Black Artists of Oklahoma Project to provide what we have taken to calling art-historical infrastructure. By this, we refer to systems that sustain things that communities of future scholars and teachers need. In this case, those things include a directory, images of artworks and exhibitions, pamphlets and other publications, interviews, oral histories, K–12 teaching materials, and so on. Scholars working in other art-historical fields have had access to this kind of infrastructure for a long time, and its use is so ingrained in the discipline’s practice that it is often taken for granted. Unaware of such a resource for Black art in Oklahoma, we began building infrastructure in the form of an archive. We draw strength from knowing that other people are also building multifaceted archives concerned with the history of Black art, perhaps most notably the Getty’s African American Art History Initiative.2 There is also a robust emergent field of Black digital humanities creating access to scholarship about the past and present.3

That said, we also recognize, following Michel Foucault, that an archive establishes “the law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events,” which is always a politically fraught consideration.4 We grapple with the ambivalence of what Jacques Derrida calls “the violence of the archive,” which ensures that “every archive . . . is at once institutive and conservative. Revolutionary and traditional.”5 There is ambivalence in every aspect related to archives and archiving. As Saidiya V. Hartman contends, “The effort to reconstruct the history of the dominated is often discontinuous with the prevailing accounts or official history, and it entails a struggle within and against the constraints and silences imposed by the nature of the archive.”6 We know that traces of Blackness often go missing from archives, if they arrive there at all, and sometimes arise in them only obliquely, through willful or careless misrepresentation. Sometimes, having surfaced, they get deliberately erased from the record. This results from the exercise of what Michel-Rolph Trouillot calls an “archival power . . . to define what is and is not a serious object of research and, therefore, of mention.”7 Furthermore, “the archive will never be sufficient,” so we affirm, with Maandeeq Mohamed, that “archival silences, gaps and ethnographic refusals” are themselves “a possible point of departure for thinking through blackness in the archive.”8

Identifying a few of Black Oklahoma history’s distinguishing features demonstrates why it warrants an art history of its own. Black people arrived in Oklahoma well before statehood in 1907, first in the 1830s along the Trail of Tears, with the Five Tribes that still reside in eastern Oklahoma. Some were enslaved people. White civilian settlers did not arrive in large numbers until much later, which makes Oklahoma one of the few states to have had a significant Black population before having a notable white population. Coincident with the foundation of All-Black towns such as Boley, Grayson, and Langston following the Land Rush of 1889, aspirations existed for Oklahoma Territory to become an All-Black state. Similar hopes arose for Indian Territory to become an all-Native American state called Sequoyah, though they were thwarted when President Theodore Roosevelt announced his preference that the two territories be combined into a single state.

Though Black history in Oklahoma often parallels African American history more generally, the state remains unique in other ways that are important both for their own sake and for how they inform broader histories of migration and mobility, of settler colonialism and Afro-Indigeneity, of imagination and possibility, of organization and resistance, and, of course, of art and artfulness. Black histories are often suppressed by structures of settler colonialism, and building the infrastructure necessary to historicize these histories is a way to resist this suppression.9 For instance, it took one hundred years for the United States to begin properly acknowledging the supremely appalling 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and it was partly through the photography of the Reverend Jacob H. Hooker, an artist we include in the project’s directory, that this recognition came about.10 Artists such as Hooker and the histories that they documented are crucial to understanding the regional histories of African American and other African diaspora art, but the historiography of Black American art usually focuses on major Black population centers, such as the South and the urban destinations of the First and Second Great Migrations (especially New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles).11 Oklahoma, a region with a unique identity, has not received its scholarly due.

For its part, the University of Oklahoma, the state’s flagship research university, has not done enough to support Black art or to account for its history. The university adhered to the state’s segregationist policies—the new state’s first law in 1907 was a Jim Crow law segregating rail coaches and cars—until that arrangement began to falter when Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, a Black woman denied admission to the university to study law, filed a lawsuit in 1946 that resulted in the 1948 Supreme Court decision Sipuel v. Board of Regents of Univ. of Okla., in which the court ruled that states could not discriminate based on race in legal education. Then, in 1950, the Supreme Court ruled in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education that the university had unlawfully segregated African American graduate student George McLaurin in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, thereby integrating graduate education. Both cases formed important precedents for Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. Despite this, the city of Norman remained a sundown town from its founding in 1889 until 1967, when George Henderson joined the OU faculty and, together with his wife, Barbara, became the first Black people to buy a house in the city.12

Although Native Americans have and continue to face structural racism and discrimination on campus, the university became an important site for the education of Native American artists (and the emergence of the Red Power movement). The Kiowa Six from Anadarko, Oklahoma—Spencer Asah, James Auchiah, Jack Hokeah, Stephen Mopope, Lois Smoky, and Monroe Tsatoke—studied with Edith Mahier in the 1920s following an invitation from the School of Art’s founding director, Oscar Jacobson.13 They were the first Native Americans anywhere to enroll at a university to study art. Mahier, born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, later illustrated the white author James Pipes’s book Ziba, a collection of stories about working-class African Americans in her home state, narrated in an approximation of vernacular speech.14 In the late 1940s and early 1950s, three Native American graduate students in art—Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe, Southern Cheyenne artist Walter Richard “Dick” West Sr., and Chickasaw/Choctaw artist Chief Terry Saul—received what we believe to be the first Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degrees ever awarded to Native visual artists.15 Nothing comparable took place for African American artists at OU during these years, because the campus was segregated. For instance, Eugene Jesse Brown founded the Department of Art at Langston University, the state’s only historically Black college or university (HBCU), in 1924 before he was thirty years old, yet he could not pursue an MFA degree at OU until the campus desegregated. He eventually received that degree in 1955, near the end of his career when he was around age sixty (fig. 1).

It was likely the 1925–26 academic year that Jacobson and his wife, Sophie Brousse, who wrote about Amazigh (Berber) art under the pen name Jeanne d’Ucel, spent traveling in Africa—specifically North Africa—that encouraged Jacobson’s interest in supporting Oklahoman artists working outside of Euro-American traditions.16 To the best of our knowledge, Ghanaian-born artist George Afedzi Hughes, currently teaching at the University of Buffalo, became the university’s first (and still only) dedicated visual arts faculty member of African descent in the first decade of this century, though the African American art critic Michele Wallace taught literature and composition in OU’s Department of English during the 1980s, amid what she identified as “manifestations of racism and residual segregation.”17

Confronting the ongoing persistence of these phenomena is not the sole province of the arts or the humanities, but art-historical work can and should contribute the effort. To that end, we have compiled a directory of artists from which histories and exhibitions can emerge. This is work that has been done bit by bit, person by person, gradually taking on a state of more general cohesion. Early on, we recognized that the information we sought was not readily available to the public, a situation that increased the urgency of the project, because it contributes to the idea that such a legacy does not exist.

Rather than start with a specific chain of events or dates to form the armature of a timeline and add artists to “fill in” that existing structure as we went along, we took the reverse course. Adopting a contextual framing of the broader history of Black Oklahomans, we began accruing the names of Black artists and their corresponding background information, adding more than 160 profiles to our database, which for now lives as data on a hard drive awaiting further shaping. The number of artists will continue to increase as we keep researching, but once this original existing data pool came together, it became relatively simple to organize a rough chronology by identifying overlaps in artists’ dates, artistic media, and schooling. By developing this timeline, we have been able to begin telling a more complete narrative of Oklahoma’s Black art history.

Because we lacked sufficient infrastructure for historicizing Black art in Oklahoma, identifying artists for the database has involved a lot of unconventional and creative research: compiling information from disparate places and blending sources that are print and digital, scholarly and anecdotal, official and otherwise. Institutional sources are helpful but also limited. One of the best institutional sources for Black arts in the state is the Oklahoma Historical Society’s webpage, “Arts and Crafts, African American,” from their Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.18 This entry of five paragraphs focuses on historical craft practices. The artists discussed are quilters, potters, and basket makers. The entry lists the full names of local artists, often their only online record, but provides no more detail than their preferred medium and town of residence.

Newspaper archives and online articles from the past century help to provide a more comprehensive record. For artists active through the beginning and middle of the twentieth century, a helpful resource is the Oklahoma Historical Society’s database of historical African American newspapers, especially after it has been filtered with keyword searches for terms like “art” and “artist.”19 For contemporary Black Oklahoman artists, we completed the same keyword searches on local newspapers’ websites—Tulsa World, The Oklahoman, The Norman Transcript—and other regional papers that often cover art exhibitions of note for their culture sections. These exhibition reviews and local interest stories on artists of the area are the most fruitful avenues for compiling lists of artists. Identifying artists and searching for them through newspaper records uncovered stories about group exhibitions, which include lists of other participating artists. University and college newspapers are likewise vital resources for identifying artists active in the past century; newspapers and student newsletters for institutions such as the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University, and Langston University sometimes list studio art majors as well as exhibitions on campus.

From these sources, a clear(er) timeline of the early history of Black art in the state began to emerge. The work of early artists such as Stephany, Serena, and Lucinda Davis, who were enslaved by the Creek man Tuskayahiniha, or “Head Man Warrior,” near Honey Springs, demonstrates that Black Oklahoman artistic production began with enslaved Black artists brought by force to the territory.20 Artmaking continued, unsurprisingly, with numerous freedmen and freedwoman, such as the weaver Chaney Richardson, born into slavery on the Charley Rogers Plantation, and again by later Black homesteaders, including Mary Scott Bass and Mary Black, two prolific quilters.21 Joining freedmen, freedwomen, and other Black settlers in Indian Territory, Black migrants introduced artistic techniques, often drawn from their familial histories, to the area. So far, our research suggests that this pattern of migration from disparate places, resulting in a radically heterogenous cultural formation, is one of the defining features of Black art with ties to Oklahoma.

Black settlers enticed by the land and opportunity that Oklahoma seemingly offered began establishing All-Black towns. The Black filmmaker Solomon Sir Jones documented them along with his travels throughout Europe and the Mediterranean in a series of films made in the 1920s.22 Though many of these All-Black towns no longer exist, one of them, Langston, is home to a highly significant place for the education of Black artists: the HBCU Langston University. Langston opened in 1897 and has been and continues to be an incredible force motivating the production of Black art in Oklahoma.23 Crucial to the establishment and growth of the university’s art department are the aforementioned Eugene Jesse Brown, Irabell Juanita Cotton, Wallace Owens, and John Arterberry. With them, a Black fine arts tradition in painting, sculpture, and drawing began to develop more fully in the state.

Beyond Langston University, many Black Oklahoman artists completed various levels of their studies across numerous Oklahoman educational institutions. Its history notwithstanding, OU has been an important locus of artistic development for Black artists within the state. Many have earned BFA and MFA degrees, as well as non-arts-related degrees, from the university in the last thirty years, including Robert Terrance “Skip” Hill, Eyakem Gulilat, and Jasmine Jones. The same is true at other institutions of higher learning, including Oklahoma State University, the University of Tulsa, Rose State University, University of Central Oklahoma, and Oklahoma City University. Additionally, several artistic collectives or fellowships in Oklahoma support Black artists. These include the Black Moon collective in Tulsa, Inclusion in Art and BLAC Inc. in Oklahoma City, the Greenwood Art Project of Tulsa, and the Tulsa Artist Fellowship.

For identifying currently practicing artists, especially younger artists, social media platforms and other online sources have been excellent resources. While not all currently practicing artists have artist websites, many have Instagram profiles to showcase their work. Through these sources, we made initial contact with three of the first four artists in our Black Artists of Oklahoma Project exhibition series, which is one of the vehicles that we have created for sharing the results of our research. Because of the abundance of material on social media, platforms such as Facebook and Instagram have functioned as dispersed digital archives of sorts, allowing us to discover past activities of artists while providing us a method of direct, instantaneous contact. That said, an older method, oral history, has proved especially helpful, as it allows us to ask living artists about previous generations and to form crucial links between past and present. Browsing social media profiles and conducting oral histories contribute to the construction of a more comprehensive and robust regional history. Still, much work remains to be done.

Throughout the process of identifying Black Oklahoman artists, we have been acutely aware that countless artists over the past several centuries have been self-taught and lack any formal documentation. Many of these artists created utilitarian or aesthetic works for themselves, for their families, or for sale. We have unfortunately realized that many of these “unknown” artists cannot be properly recognized in our database, but their artwork and lasting influences will continue to be represented as “absent presences” until we learn their names.

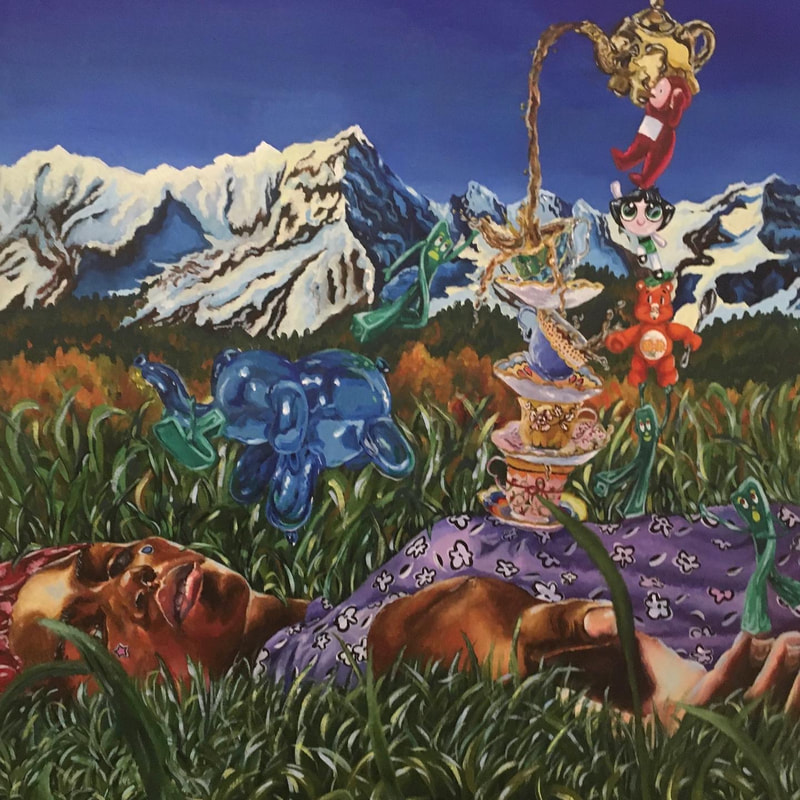

Because assembling our archive has made it abundantly clear that there is a plethora of young Black artistic talent across Oklahoma, we decided to contribute to the archive through hosting and documenting exhibitions. With support from the OU School of Visual Arts, we coordinated four Black Artists of Oklahoma Project exhibitions in the school’s Spotlight Gallery during the 2022–23 academic year. The first exhibiting artist, Karina Cunningham (b. 2000), is originally from Colorado Springs, Colorado, and then attended Edmond High School in Oklahoma and the University of Tulsa. Her show, Karina Cunningham’s Playhouse, addressed complex psychological and social issues related to childhood and coming of age through figurative acrylic paintings that incorporate depictions of children’s toys from the late 1990s and early 2000s and landscapes reminiscent of Colorado (fig. 2). The only photographer in the series, C’yera Coleman (b. 1999) from Paris, Texas, attended OU, where she studied psychology. Interest in capturing the outward image of the inner self suffused the photographs in her show C’yera Coleman’s Psyche of a Muse. Her work utilizes saturated hues, deliberate cropping, and dynamic models to create “psychological portraits” of her sitters.24

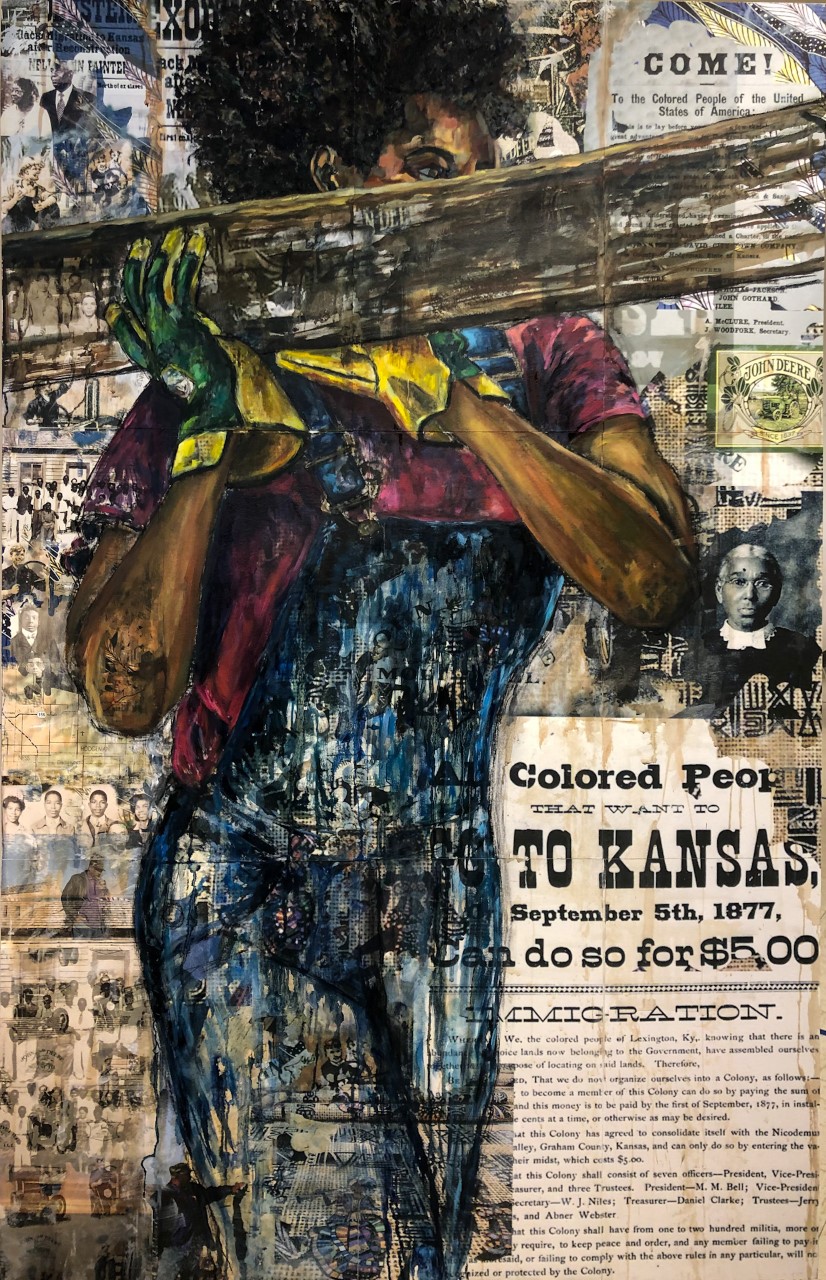

The third artist in the series, Shyanne Dickey (b. 1996), attended Oklahoma State University, where she studied studio art. Born in Tucson, Arizona, she grew up in various towns across the West. Shyanne Dickey’s Unveiling a Hidden History examined her family’s history as Exodusters, a large group of formerly enslaved individuals in the late nineteenth century who, as Dickey describes, “migrated out of the South to Kansas in hopes for farmland and, honestly, a better life” (fig. 3).25 The final artist in the series, Christian Dixon (b. 1997), moved to Oklahoma from Missouri in 2016 after joining the Air Force. In his exhibition Christian Dixon’s Inner Reality, Dixon’s surreal oil paintings strived to “connect with others on an unconscious level, and give a sense of validation to those who have an appreciation of nature, and to those who seek answers to some of the deeper questions in life” (fig. 4).26

Of the four artists, Dickey grapples most directly with our project’s interest in Black archival presence, so her work merits detailed scrutiny in that regard. Much of Dickey’s painted and collaged portraiture centers her female relatives, including her mother, sisters, and five-times great-grandmother, Eliza Bradshaw, who “was able to farm and to own land in a place where she wasn’t expected to be successful, and where she also faced a lot of heartache and tribulations but was able to maintain her strength and stability through her family and through her faith.”27 With her portraiture, much of which draws from and includes archival photographs, Dickey emphasizes to audiences that the popular image of the Western farmer as a white male is not always accurate. She states that she wants her work to convey that the farmer “can be Black . . . a woman, and educated. And I think this idea of success can come from anywhere. You know?”28

Over the course of several years, Dickey has experimented with different forms of image transfer for her collages and utilized a variety of papers, gels, and inks.29 This mixture of media is appropriate given the layered histories she addresses. Her painting The Load (2020), for example, spotlights a Black female farmer whose form is comprised of varied archival materials. The bottom right corner contains a reproduction of the poster “All Colored People that want to go to Kansas . . . ,” created in 1877 by the Nicodemus Town Company to entice Black settlers to the still-extant town of Nicodemus, Kansas, the first All-Black settlement west of the Mississippi.30 Dickey’s ancestors settled in and helped construct Jetmore, Kansas. Her use of posters in The Load emphasizes the seeming “freedom” that moving from the South offered Black citizens. Dickey’s incorporation of portions of the cover of Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction by Nell Irvin Painter in the upper-left corner of the painting further showcases her knowledge of Exoduster history and scholarship, of which her own artwork is now a part.31

In addition to the numerous archival and familial photographs comprising The Load’s background, Dickey has incorporated advertisements and “call-outs” to iconic farming equipment brands, including John Deere, which show up in old ads in the painting’s background and in the color of the female figure’s gloves. To source the archival photographs used in The Load, such as the portrait of Bradshaw at the woman’s elbow, Dickey had to “dig through” family photo albums, utilize the Library of Congress’s databases, and do a lot of “just Googling the Exodusters.”32

Dickey’s title, The Load, connects both physically and metaphorically to the burden that the painting’s central figure is carrying. While clearly a wooden object, perhaps a fence post, the woman’s load also refers to the familial legacy of farming under tough conditions, which Dickey has identified in both her own artwork and her mother’s career as a farmer. She notes that she sees her mother as “carrying out that . . . legacy, and that hasn’t died . . . we’re still carrying out what my five-times grandmother suffered through.”33 When asked why she has focused so extensively on her family’s history as Exodusters, Dickey emphasizes that she did not see much representation of Black farmers, specifically Black female farmers, in museums or schools growing up but that such history should not “be just thrown off” because it is perceived as “not that important.” Rather, she asserts that “it’s not fair for someone to hold that standard of what’s important in history and what’s not important to history in history,” including her own familial legacy on the Plains.34 Such challenging of “established” histories and oppression of Black experiences through archival explorations is exactly what we aim to achieve with the Black Artists of Oklahoma Project.

Our work on this project has followed cues from artists to ensure that the communities who will hopefully benefit from what we are doing have a deciding role in shaping what we produce. Rather than imposing a preconceived art-historical notion onto the material we assemble into an archive, we want the infrastructure we make to respond in an ongoing way to people’s needs, to thrive because it is used. This means proceeding with a vision that originates in and responds to community input. That input began by working with currently practicing artists, something that will continue to be augmented by other forms of engagement moving forward. We are working patiently and carefully, and it is too soon to say what forms the project will take in the future. We are currently entering a planning period to identify next steps, though current activities—archiving, exhibiting, and publishing—will continue. We want the project to stay lively, as archives have a tendency to gather dust once their initial purposes have been served, lying fallow until they become of interest to a historian for other reasons. By neither centering nor disregarding the historian’s point of view, we hope that our project has utility in communities beyond academia or the art world, that it joins people together to share in the work of art and history. For now, we are focused on deepening our existing community relations and building new ones as we identify the way forward for the project. Regardless of what shape it ultimately takes, we proceed knowing that when people are equipped with a greater understanding of the past and of culture, they can act more thoughtfully in the present. Our own first steps of developing the Black Artists of Oklahoma Project have already taught us much about past and present alike. We look forward to learning—and changing—more.

Cite this article: Olivia von Gries and Robert Bailey, “Archival Assembly: The Black Artists of Oklahoma Project and Art-Historical Infrastructure,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.17282.

Notes

Thanks are due to curator Hadley Jerman at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art and Scout Hutchinson, a curatorial intern there, for early work on the project, as well as the Robert S. and Grayce B. Kerr Foundation for supporting subsequent work done at the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of the Art of the American West. Additional thanks are due to Kalenda Eaton, Pete Froslie, Emily Burns, Barry Roseman, Marie Casimir, and Pablo Barrera for their contributions and assistance.

- While the title of our project is a placeholder and may change in time, we gave thought to our language choices, preferring “Black Artists of Oklahoma Project” because it identifies a process-based initiative that makes space for diverse people of African descent, including those who were not born in the state or even in the country, working in any visual medium. ↵

- See Getty, “African American Art History Initiative,” 2018–present, accessed May 15, 2023, https://www.getty.edu/projects/african-american-art-history-initiative. ↵

- Other Black digital humanities projects with some similarities to ours include Zirwat Chowdhury, “Blackness, Immobility & Visibility in Europe (1600–1800)—A Collaborative Timeline,” Journal18 (September 2020), https://www.journal18.org/5175; University of Delaware, “Colored Conventions Project,” 2012–2020, accessed May 15, 2023, https://coloredconventions.org; Tiffany Momon and Torren Gatson, co-directors, “Black Craftspeople Digital Archive,” 2019–present, accessed May 15, 2023, https://blackcraftspeople.org. On Black digital humanities, see Roopika Risam and Kelly Baker Josephs, eds., The Digital Black Atlantic (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021). There are also relevant chapters in Dorothy Kim and Jesse Stommel, eds., Disrupting the Digital Humanities (n.p.: punctum books, 2018); Dorothy Kim and Adeline Koh, eds., Alternative Historiographies of the Digital Humanities (n.p., punctum books, 2021). Other helpful resources include the African American Digital and Experimental Humanities at the University of Maryland, accessed May 15, 2023, https://aadhum.umd.edu; and the Digital Ethnic Futures Consortium, 2021–present, accessed May 15, 2023, http://digitalethnicfutures.org. ↵

- Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language (New York: Pantheon, 1972), 129. ↵

- Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 7. Emphases original. ↵

- Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 2022), 13. ↵

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon, 1995), 99. ↵

- Maandeeq Mohamed, “Somehow I Found You: On Black Archival Practices,” C Magazine 137 (Spring 2018): 10. On archival silence, see David Thomas, Simon Fowler, and Valerie Johnson, The Silence of the Archive (Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman, 2017); Michael Moss and David Thomas, eds., Archival Silence: Missing, Lost, and Uncreated Archives (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021). ↵

- For a gateway into Black history in Oklahoma, see Oklahoma State University Libraries, “African Americans and Oklahoma History,” accessed May 15, 2023, https://info.library.okstate.edu/african-american-studies/oklahoma. Another helpful online resource is the Oklahoma Historical Society, “Black History is Oklahoma History,” accessed May 15, 2023, https://www.okhistory.org/blackhistory. See also Cheryl A. Coleman, Before the Land Run: The Historic All-Black Towns of Oklahoma (self-published, 2019); Hannibal B. Johnson, Acres of Aspiration: The All-Black Towns in Oklahoma (Fort Worth, TX: Eakin, 2007); Hannibal B. Johnson, Black Wall Street 100: An American City Grapples with Its Historical Racial Trauma (Fort Worth, TX: Eakin, 2020); Rochelle Stephney-Roberson, Impact: Blacks in Oklahoma History, 2nd ed. (Oklahoma City, OK: Things With Impact, 2021). See also Davis D. Joyce, ed., “An Oklahoma I Had Never Seen Before”: Alternative Views of Oklahoma History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994); Sarah Eppler Janda and Patricia Loughlin, eds., This Land is Herland: Gendered Activism in Oklahoma from the 1870s to the 2010s (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021). Also illuminating is the National Public radio podcast, Focus: Black Oklahoma, December 21, 2020–present, accessed May 15, 2023, https://www.npr.org/podcasts/953571690/focus-black-oklahoma. ↵

- See Karlos K. Hill, The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: A Photographic History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021). ↵

- See, for example, exhibition catalogues such as Valerie Cassel Oliver, ed., The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2021); Linda Goode Bryant, Thomas J. Lax, and Lilia Rocio Taboada, eds., Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2022); as well as scholarly monographs, including Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Rebecca Zorach, Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago, 1965–1975 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019). ↵

- On Norman as a sundown town, see Michael S. Givel, “Evolution of a Sundown Town and Racial Caste System: Norman, Oklahoma from 1889 to 1967,” Ethnicities 21, no. 4 (August 2021): 664–83. For his account of living and working in Norman, see George Henderson, Race and the University: A Memoir (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010). ↵

- See A World Unconquered: The Art of Oscar Brousse Jacobson (Norman: Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, 2015); Gunlög Fur, Painting Culture, Painting Nature: Stephen Mopope, Oscar Jacobson, and the Development of Indian Art in Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019); Kiowa Agency: Stories of the Six (Norman: Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, 2020). ↵

- James Pipes, Ziba (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1944). ↵

- Alicia Harris, ed., Ascendant: Expressions of Self-Determination (Norman: School of Visual Arts and Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, 2022). ↵

- Jeanne d’Ucel, Berber Art: An Introduction (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1932). ↵

- Michele Wallace, Invisibility Blues: From Pop to Theory, new ed. (London: Verso, 2008), 168. See also Michele Wallace, Dark Designs and Visual Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004). ↵

- Jamie Johnson, “Arts and Crafts, African American,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed November 15, 2022, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=AR018. ↵

- “African American Newspapers,” The Gateway to Oklahoma History, Okahoma Historical Society, accessed May 15, 2023, https://gateway.okhistory.org/explore/collections/AFRAN. ↵

- “Tuskayahiniha Farm,” Sankofa’s Slavery Data Collection, accessed July 2021, https://sites.rootsweb.com/~afamerpl/plantations_usa/OK/tuskayahiniha.html. ↵

- Johnson, “Arts and Crafts.” ↵

- “Solomon Sir Jones Films, 1924–1928,” Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, accessed May 15, 2023, https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/solomon-sir-jones-films-1924-1928. ↵

- Langston University, “History of Langston University,” accessed December 14, 2022, https://www.langston.edu/about-us/resources/history-langston-university. On art at HBCUs, see Richard J. Powell and Jock Reynolds, eds., To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (Andover, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and MIT Press, 1999). Unfortunately, Langston was not among the HBCUs participating in this exhibition. ↵

- C’yera Coleman, interview with Olivia von Gries, October 10, 2022. ↵

- Shyanne Dickey, interview with Olivia von Gries, October 14, 2022. ↵

- Christian Dixon, artist statement provided to Olivia von Gries, October 2022. ↵

- Dickey interview. ↵

- Dickey interview. ↵

- Dickey interview. ↵

- Kansas Historical Society, “All colored people that want to go to Kansas,” accessed December 15, 2022, https://www.kshs.org/km/items/view/702; National Park Service, “Kansas: Nicodemus National Historic Site,” accessed December 15, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/articles/nicodemus.htm. On Nicodemus, see Justin Hosbey, “‘I Looked with All the Eyes I Had’: Black Women’s Vision and the Stakes of Heritage in Nicodemus, Kansas,” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 45, nos. 3-4 (2016): 303–47. ↵

- Nell Irvin Painter, Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction (New York: W. W. Norton, 1992). ↵

- Dickey interview. ↵

- Dickey interview. ↵

- Dickey interview. ↵

About the Author(s): Olivia von Gries is a PhD candidate in Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma. Robert Bailey is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Oklahoma.