Asian American Art, Pasts and Futures

Guest Editors

Contributors*

Serena Qiu, “In the Presence of Archival Fugitives: Chinese Women, Souvenir Images, and the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair”

Yinshi Lerman-Tan, “Sadakichi Hartmann’s American Art: Citizenship, Asian America, and Critical Resistance”

Karen Fang, “Commercial Design and Midcentury Asian American Art: The Greeting Cards of Tyrus Wong”

Catherine Damman, “Art, Technology, Crisis: The Work of Carl Cheng”

Sadia Shirazi, “Returning to Dialectics of Isolation: The Non-Aligned Movement, Imperial Feminism, and a Third Way”

Eunyoung Park, “Beyond Conflict, Toward Collaboration: The Korean American Arts Community in New York, 1980s–1990s”

Jenni Sorkin, “Time Goes By, So Slowly: Tina Takemoto’s Queer Futurity”

Ellen Tani, “Un-Disciplining the Archive: Jerome Reyes and Maia Cruz Palileo”

Hsuan Hsu, “Beatrice Glow and the Botanical Intimacies of Empire”

Conclusion

Aleesa Alexander, “Asian American Art and the Obligation of Museums”

Introduction

by Marci Kwon

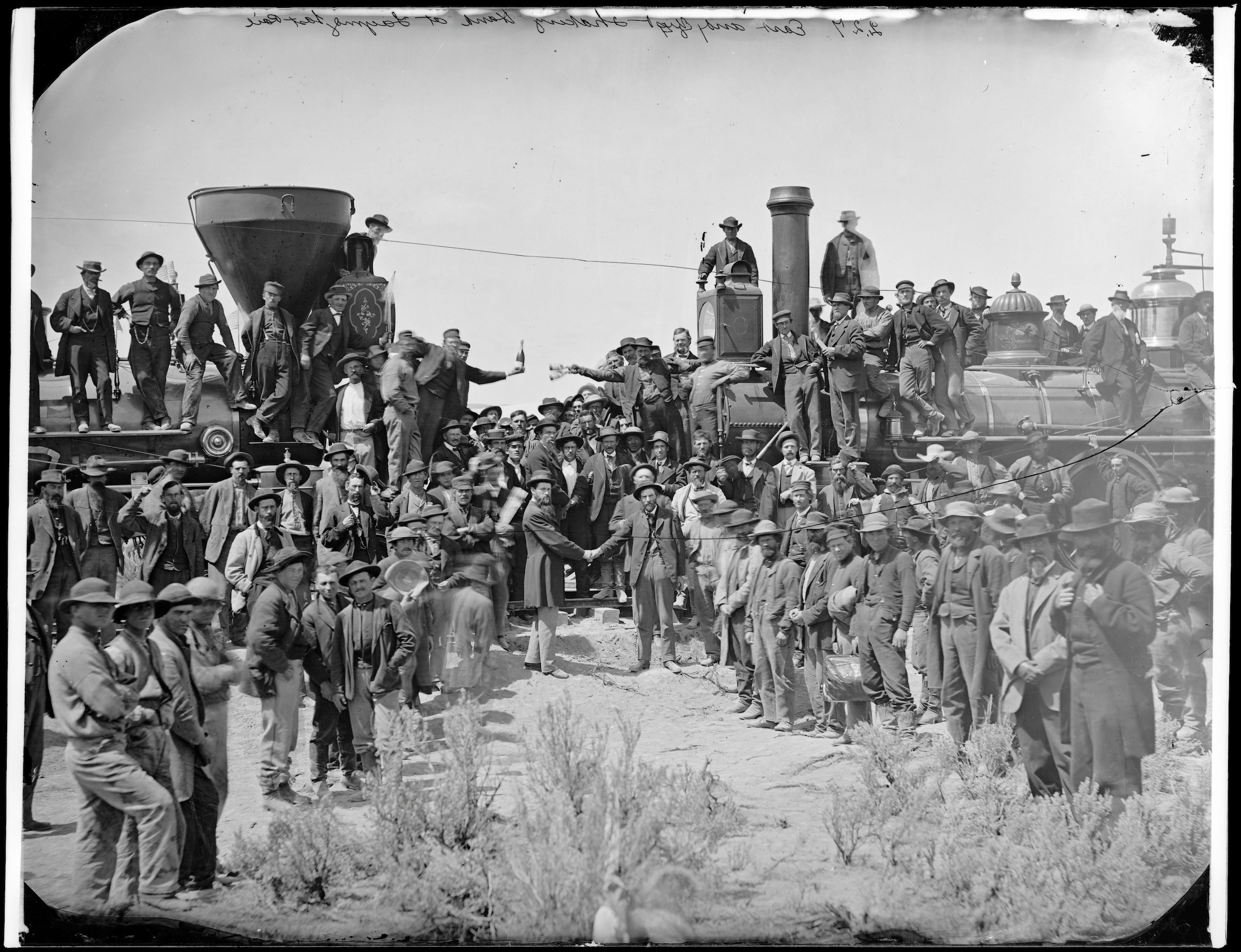

Scholars of Asian American studies and American art know this image. Andrew Russell’s Meeting of the Rails, Promontory, Utah (fig. 1) commemorates the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869. The photograph is as dense with white male bodies as any American history painting, and this is surely the point. Two men hang off the hulking locomotives, reaching across the leached sky in a vain attempt to crown the moment with a toast. The gap between bottle and flute is bridged by the handshake of the men in the foreground. Their clasp clinches the illusion of east meeting west,1 as Russell would later retitle the photograph.2 This press of flesh is transformed into the vanishing point by the orthogonal lines formed by the workers, diagonals that carve the conventions of spatial representation from ground and sky, an “optical armature,” as Jennifer Roberts described it, naturalizing their possession of this space, this land.3

Within Asian American studies, Russell’s photograph has been taken as an allegory of invisibility. The picture has been discussed for its dearth of Chinese railroad workers, who made up 90 percent of the labor force of the Central Pacific Railroad.4 Approximately twenty thousand Chinese workers laid hundreds of miles of track, blasted through the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and in 1867, struck for improved working conditions and equal pay with their white counterparts.5 The fruits of their labor are consolidated in the famed last spike (fig. 2), also known as the golden spike, which ceremonially united the two tracks built by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads into a single unbroken line. Union Pacific vice president Sam Durant and Central Pacific Railroad president Leland Stanford were charged with tapping the golden nail into place with a silver maul. At the decisive moment, however, their blow missed.6 Despite this failure, spike and maul were quickly whisked away and replaced with an ordinary wood rail, secured into place with ordinary iron nails. “The Chinese really laid the last tie and drove the last spike,” wrote a journalist who witnessed the scene.7

Today the golden spike and silver maul reside at the institution built by Leland Stanford’s fortune, a fortune that was itself largely created from Chinese labor.8 Like a relic of the true cross, the golden spike was both witness and active participant in this formative moment of American empire—a moment that is often taken as a triumphant example of American ingenuity, rather than a driver of settler colonialism and genocide. In the words of historian Manu Karuka, the golden spike “symbolically finalized the industrial infrastructure of a continental empire where none had existed before.”9 Created from $350 worth of gold by the William T. Garrett Foundry of San Francisco, it is engraved with the dates of the groundbreaking and completion of the railroad, along with the names of railroad officers and directors.10 Like many objects of commemoration, it remembers certain things by forgetting others. It alchemizes violence into gold, labor into capital, and history into object, consolidating the unquantifiable into a single treasure that can be weighed, valued, and collected.

Yet, the golden spike also remembers in ways that contradict the intention of its makers. Its gleaming surface symbolizes monetary value, yes, but it also reflects the environment and the faces of the people who encounter it. Like Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial, to stand before the spike is to see the names of others scarring your face. To look is to be implicated. And behind these scars of proper names are those who are not named: the thousands of Chinese workers who built the railroad, and the millions of Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian people killed in the Vietnam War. They are at once present and absent behind the names gouged into gold and granite. They are ghosts.

Russell’s photograph also holds a ghost. Although there are several spectral blurs among the crowd, only the figure at center left shows his back. Based on the pose and clothing, historian Gordon Chang has recently suggested that the figure might be that which many Asian Americans have longed for: a Chinese worker.11 It is impossible, however, to know for certain.

Hovering between invisibility and presence, identity and obscurity, this figure embodies the complexities of placing Asian American artists within art history. Like them, he is both in plain sight and impossible to see. To call him Asian American, or to claim his significance for Asian American history, at once sharpens the blur of his body, making him more visible, and saddles him with a label that would have puzzled him. In his ghostly unknowability, he embodies what has been described as the “fundamental paradox” of minoritarian discourse: “that ‘identity’ is the very ground upon which both progress and discrimination are made.”12

How can we honor the unknowable figure in Russell’s photograph? What does it mean to claim him as Chinese, and name him as Asian American? How do we write about him without consigning him to the extreme poles of oblivion or perfect visibility? What can he teach us, and how does our desire for what he can teach us constrain him? Are his shoulders not stooped enough already? What did he do before this picture was taken, and what did he do after? What would it mean to queer him? How can we see the women who are nowhere in this picture, and honor their specific burdens and joys? Who loved him, and whom did he love? What did he dream about?

⸹

This In the Round was first conceived before the COVID-19 pandemic, during the final year of the Trump Administration. Its call for papers went out during quarantine, amid a rise in xenophobic rhetoric and anti-Asian hate, and in the wake of the murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd (the latter abetted by Hmong American police officer Tou Thao) and the subsequent uprising against police brutality and anti-Blackness. Our deadline for first drafts was weeks after white supremacists stormed the United States Capitol Building. And soon after we returned these drafts to our authors, Xiaojie Tan, Daoyou Feng, Soon Chung Park, Hyun Jung Kim, Suncha Kim, and Yong Ae Yue were murdered in Atlanta by a gunman motivated by racist, misogynist hate. It is a bitter thing to know that these events will lead some to call the topic of Asian American art relevant or important, as if this epidemic of violence was at all a new phenomenon; as if a racialized subject is only worthy of regard in relation to white supremacy.

My coeditor and I are employed by Stanford University, an institution built by the wealth of the transcontinental railroad. It is also built on unceded Muwekma Ohlone land, in part by Chinese laborers who, as recent archeological work has uncovered, planted the palm trees that line Palm Drive, the main artery of campus.13 Every day that I walk across these grounds, I am reminded that Asian American history is not simply the history of Asian Americans, but the history of race, capitalism, labor, settler colonialism, imperialism, legal exclusion, incarceration, gendered violence, and war—and their entanglement—in American history. These are abstract words and concepts whose precise meanings do not remain stable but are contingent upon their specific historical moment. They also name structures that exert undeniable power, in both past and present; in both elsewhere and here; where I work and live; in what I read, see, and study; in the body I inhabit; and in the bodies of all racialized subjects.

The nine essays that comprise this In the Round section address a range of topics, including the display of Chinese American women at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition; Hallmark greeting card design; modernity’s racialization of labor; and the entwinement of scent and colonialism. Together, they show Asian American art as polyvocal rather than monolithic, encompassing a range of ethnicities and experiences, and intersecting with gender, sexuality, and class. What unites the essays is an attentiveness to the myriad ways Asian Americans have engaged with a range of overlapping power structures that seek to control and determine their existence. In this, many of the authors find lessons in Asian American studies, whose detailed investigations of these structures and longstanding emphasis on transnational perspectives offer important lessons for historians of American art. As Lisa Lowe has shown, to believe in the liberal humanist ideals at the heart of Western modernity, the US nation-state included, requires a willful forgetting of the unfreedom at their core: the entwined histories of settler colonialism, chattel slavery, and indentureship. Race is a “trace of liberal forgetting.”14 Race is all that which the myth of America attempts to repress. Race is my reflection in the spike’s golden gleam, and the names that float across my skin.15

Asian American art helps us see these things. It is more than a superficial addition to the history of American art, a single week on a syllabus or a single painting on a wall, a bauble to make old narratives appear more diverse. Rather, Asian American art allows one to catch sight of their own reflection in the golden spike, and to wonder how this mirage was created, whom it has obliterated, and how it may be destroyed. The study of Asian American art is crucial to critically examining what is meant, and who is being addressed, by terms such as American art, American, art, and art history.

At the same time, as Anne Anlin Cheng pointed out more than twenty years ago, in the United States a person of color is seen as worthy of attention only when they have suffered visible harm.16 Studying the work of Asian American artists is perhaps one way to sidestep this obsession with injury. To think and feel with Asian American artists requires one to fiercely guard the knowledge that they and their work are more than illustrations of pernicious structures, or even tools to dismantle them.17 Although they may be both, they provide other things as well. They offer a perspective on that which often remains submerged within more abstract scholarly accounts: the multiple and complex ways Asian Americans have lived, worked, created, and imagined in relation to a world that seeks ever more devious ways to homogenize and dehumanize them. Their work offers the glimmer of not just what we have been fighting, but what we are fighting for.

Asian American Art: A Brief Historiography

Artists and makers of Asian descent have been working in the United States since their arrival on its shores.18 They ran photography studios; created and participated in arts organizations; showed in major exhibitions such as Whitney annuals; and illustrated the covers of popular magazines such as Time and Life. Research for the survey text Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970 has identified more than one thousand artists of Asian descent working in California alone during its chronological span.19 The number is staggering, indicating the deep significance of art and art making for Asian Americans but also the volume of work that remains to be studied, and likely has been lost.

As Gordon Chang has noted, early critics and art historians “never could quite understand how to label or characterize their work: Were the artists Americans, Asians, or some other sort of animal? Was their artwork American, Japanese, Chinese, or something else? Oriental? Eastern?”20 Chang suggests the congruence between aesthetic classification and the racialization of Asian Americans in the early twentieth century. The interest in designating a work as east or west, Chinese or American, betrays an obsession with national origins that parallels the exclusionary logic of contemporaneous immigration policies, and moreover assumes that these categories can be easily separated. To this point, artistic techniques originating in Asia were frequently designated as ancient by US critics, echoing the Orientalist association of Asia as belated in relation to a modern West.21

These issues of classification irrevocably shifted with the social foment of the 1960s. In 1968, University of California Berkeley graduate students Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka coined the term “Asian American” to replace the racist and colonialist designation “oriental” and unite the various Asian ethnic groups participating in the radical Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) into a single political entity.22 Established at San Francisco State College (later University), the TWLF was a radical student movement that critiqued the school’s complicity with US militarism and sought the establishment of an anticolonial “Third World” curriculum.23 The movement’s name spoke to its broad coalition (which included Black, Latinx, and Asian American students) as well as its radical politics: the 1955 African-Asian Bandung Conference popularized the use of Third World to describe the bloc of Non-Aligned countries, many of them former colonies.24 After a year of escalating protests, the student strike at San Francisco State ended with the establishment of the College of Ethnic Studies in 1969, the first school of its kind, and the beginning of ethnic studies, Asian American studies included.

In the decades since the Asian American movement, a small but active cohort of scholars has worked tirelessly to trace new lines of inquiry in the study of Asian American art. As a college student in New York, Margo Machida witnessed the anti-war, Civil Rights, and Third World Liberation movements, while simultaneously becoming aware “that parallel art worlds, support networks, and budding institutions existed alongside the largely white dominated art ‘mainstream.’”25 Her early criticism and curatorial work included projects for important community arts organizations, including the Basement Workshop and Asian American Arts Centre, and for nearly four decades, her work has set the standard for the study of contemporary Asian American artists.26 Machida’s 2009 book Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Arts and the Social Imaginary offers a trenchant overview of the debates about Asian American art and identity from the 1960s through the global turn of the 2000s.27 The book elucidates the work of ten artists of various ethnic backgrounds in relation to issues of racialization, trauma, migration, and transnational circulation, an analysis Machida based on extensive interviews. Her work models collaboration instead of top-down authority, suggesting the way ethical challenges engender (rather than inhibit, as is often argued) new methods and lines of inquiry.

Mark Dean Johnson likewise witnessed the Civil Rights Movement while a college student. As a young faculty member at Humboldt State University in the 1980s, Johnson worked closely with Native artists and communities, an experience he describes as key to “my conception of my own responsibility as an academic.”28 After joining the faculty of the San Francisco Art Institute, and later San Francisco State, Johnson began an exhaustive investigation into the work of historical Asian American artists. Aside from his extensive curatorial career, discussed by Alexander in the concluding essay for this section, Johnson coedited the aforementioned Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970 with Gordon Chang and Paul Karlstrom, the culmination of a years-long research project conducted in part at Stanford University.

Karin Higa was working on a dissertation on the subject of Japanese American photographers in Los Angeles at the time of her death in 2013. As a curator at the Japanese American National Museum, Higa assembled shows of art made in internment camps (1992), on furniture maker George Nakashima (2004), and on contemporary artists Bruce and Norman Yonemoto (1999), among others. The daughter of Kazuo Higa, art historian and director of Los Angeles City College’s Da Vinci Art Gallery, Higa grew up around artists. Her essay on photographer Robert A. Nakamura, who was interned with Higa’s father and took iconic photographs of Black artists such as Betye Saar, discusses the solidarity among Black and Asian American artists in 1960s and 1970s Los Angeles, who both knew “all too well the consequences of looking like the enemy.”29

These scholars offer crucial lessons for the future study of Asian American art. Their formation in 1960s social movements gave them a clear sense of the political stakes of their work and also attuned them to the importance of cross-ethnic coalitions and perspectives. Their subjects have required them to traverse boundaries not typically crossed by art historians: between academic and curatorial; scholarship and activism; art and community; historical and contemporary. Their work suggests the flexibility, collaboration, and above all, trust required to produce scholarship on artists whose work and histories are often located in private residences rather than institutions, in memories rather than archives, and whose affective charge, especially to the communities to which they belong, greatly exceed their monetary value.

In addition to Machida, Johnson, and Higa, Anthony W. Lee and ShiPu Wang have made significant contributions to the understanding of artists of Asian descent in the United States. Lee’s book on San Francisco Chinatown (2001), his edited volume on the writings of Yun Gee (2003), and his remarkable study A Shoemaker’s Story (2008) demonstrate the inseparability of domestic and international histories in the lives of Chinese immigrants.30 Over the course of two meticulously researched books and a major exhibition, ShiPu Wang has similarly shown how a diasporic perspective allowed artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Miki Hayakawa, and Chiura Obata to critically engage the idea of Americanness in light of war, nationhood, and race.31 Finally, important scholarly interventions have come from specialists of global contemporary art, including Midori Yoshimoto and Joan Kee.32 Their work shows the limitations of subfields such as Asian, American, and modern and contemporary art and reimagines Asian American art as connoting connection and movement rather than temporal or geographic borders.

“Asian American” Art and its Discontents

In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act (Hart–Celler Act) abolished the national origin quotas and exclusionary policies that had defined United States immigration policy from the mid-nineteenth century, leading to an influx of immigrants from countries such as Korea, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.33 American warmongering in Southeast Asia also created waves of refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. In the face of these demographic shifts, the compiling of Asian ethnic groups under a single term began to appear less as a strategy of solidarity and more as a flattening of difference. Since the 1990s, scholars of Asian American studies have productively challenged and critiqued the idea of a single Asian America and its assumptions of cultural nationalism. Moreover, feminist and queer critiques by scholars including Elaine Kim and David Eng have laid bare the heteropatriarchal, masculinist assumptions embedded in early conceptions of the term Asian American.34

The most influential scholarly intervention of this period arguably came from Lisa Lowe, who showed how the figure of the white American citizen has been historically defined against the Asian immigrant, who is at once assimilated and perpetually alien to the nation-state.35 In contrast to the cultural nationalist assumption of a singular Asian America, Lowe focuses instead on the “heterogeneity, hybridity, and multiplicity” of the term. In Lowe’s 1996 book, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics, a trenchant chapter on the contemporaneous phenomenon of multiculturalism is included, in which she writes:

[Multiculturalism] levels the important differences and contradictions within and among racial and ethnic minority groups according to the discourse of pluralism, which asserts that American culture is a democratic terrain to which every variety of constituency has equal access and in which all are represented, while simultaneously masking the existence of exclusions by recuperating dissent, conflict and otherness through the promise of inclusion.36

Lowe’s discussion helpfully situates recent calls for diversity and representation within a longer history of multiculturalism, anticipating critiques of these strategies as superficial concessions designed to prevent structural change.37 The wisdom of this critique is apparent in a recent, deeply disturbing use of the term Asian American art.38

On November 20, 2020, First Lady Melania Trump presided over the unveiling of Isamu Noguchi’s sculpture, Floor Frame (fig. 3), in the Rose Garden. On her official Twitter account, Trump wrote that the work “represents the important contributions of Asian American artists.”39 This point was echoed in an article for ArtNews written by Stewart D. McLaurin, president of the White House Historical Association. “As the first work of art by an Asian American artist in the White House Collection,” he wrote, “it is a milestone for the Asian American community.”40 Like most public relations stunts undertaken by the Trump Administration, the announcement’s shameless hypocrisy seemed so over the top that it felt like a troll. The First Lady’s self-congratulatory mention of the “important contributions of Asian American artists” stood in direct contrast to the administration’s xenophobic anti-Asian rhetoric around the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, as art historian Amy Lyford pointed out, Noguchi was voluntarily interned during World War II, an experience that made him aware of the hypocrisy of being claimed as American.41 The event’s flagrancy at least has the benefit of making absolutely clear the way superficial tokens of recognition abet extant structures of power through the management of dissent. The lesson for the study of Asian American art is likewise clear: mere visibility or inclusion within dominant structures, such as extant narratives of America or American art history, often serves to uphold those structures.

This point has also been discussed by scholar Susette Min, who, as a curator in the 1990s, saw the representational burden placed upon artists by the term Asian American. Like Darby English, she argues that such labels freeze artists within a “ready-made set of interpretations already embedded in a viewer’s purview or imagination,” and is moreover particularly ill-suited to account for the practices of artists whose work “remains both open and multiple, and therefore elusively uncategorizable.”42 To this point, she helpfully reframes Asian American art as a discourse rather than a discrete identity category.43 Throughout this issue, our own use of Asian American art accords with Min’s important revision, as well as Lowe’s earlier emphasis on heterogeneity and multiplicity. Yet, in her emphasis on aesthetic indeterminacy as a defense against categorization, Min may have been too optimistic.

In fact, Noguchi’s Floor Frame reconfigures categorization itself. The work consists of two distinct bronze sections: beams conjoined at a right angle, and a smaller piece that sits flush to the floor. The gap between them creates the illusion of a single form that dips below the ground before remerging. As Noguchi wrote, “Thinking of the floor, I made Floor Frame. I made other pieces in relation to floor space at the time, but this seemed to best define the essentiality of the floor, not as sculpture alone but as part of the concept of floor.”44 The statement situates Floor Frame as part of the artist’s longstanding investigation of the co-constitutive nature of sculpture and the world around it. For Noguchi, the “essentiality” of the floor can only be apprehended in relation to the forms around it. In this work, the floor at once supports the sculpture and is a plane that can be breached by its bronze beams. It is unclear if the frame of Floor Frame is broken or incomplete, for the two pieces do not cohere into a closed structure. Thus the frame of Floor Frame does not enclose, but moves through the floor. “To frame” is not simply to confine within a single definition but to show how all things are defined in relation to each other. Floor is “space” rather than a solid.

Yet Floor Frame’s complex investigation of categorization does not prevent it from being racialized. Trump’s full tweet about Floor Frame reads: “The art piece is humble in scale, complements the authority of the Oval Office, & represents the important contributions of Asian American artists.” The word “humble” rehearses the racist trope of Asian American men as less vigorous or assertive than white men, a meaning made explicit in the next clause: “complements” may have well been “submits to.”45 The sculpture’s abstract character is no defense against this racist description. It is also conceivable that Floor Frame’s lack of overt representational content offered a blank into which Trump could project her racist fantasies of the work’s meaning, rather than a bulwark against such fantasies. Perhaps aesthetic indeterminacy and the refusal of categorization as an alternative to racialization is no alternative at all.

Tolerating the Paradox

The example of Noguchi at the White House presents a paradox. To be clear, in describing the way the sculpture—and Noguchi—have been racialized and mobilized by right-wing forces, I am not saying that they are defined solely by their misuse. Floor Frame exceeds both its racist framing and the more politically palatable, but no less reductive, reading of it as a mere illustration of the artist’s identity. At the same time, Noguchi’s life, his art, and his work’s reception in the present is conditioned by the structures that have historically sought to circumscribe his existence: racism, xenophobia, and nationalism.46 Just as Floor Frame is at once enclosure and opening, Asian American artists are ineluctably confined by and exceed the structures in which they exist.

Art offers a place to linger with this paradox. As scholar Timothy Yu has observed, the past thirty years of Asian American studies have been shaped by a text authored by an artist: Dictée (1982) by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha.47 Born in South Korea in 1951, Cha studied art and comparative literature at University of California, Berkeley, and film theory in France with scholars such as Christian Metz, Raymond Bellour, and Thierry Kuntzel. Working across performance, video, and poetry, her art explores issues of language, translation, and loss, which are also key concerns in Dictée. Published posthumously after her rape and murder in 1982, the experimental text intersperses images and snippets of biography, Greek and Korean mythology, and history written in English, Korean, and French.48 With its fractured, recursive form, the text evokes experiences of memory, trauma, and geographical displacement. As Yu implies, Dictée’s purchase for Asian American studies arguably lies in its paradoxical ability to deconstruct and assert the importance of structures such as race, identity, and history: “Art becomes the crucial context within which issues of theory and identity can be played out, where acts can be both referential and performative, both abstract and concrete.”49

If art is both abstract and concrete, referential and performative, so too is race.50 Art’s ability to embody this paradox makes it a potent site of investigation for a racialized subject. The ethical challenge of writing about Asian American artists is to respect, rather than to solve, the paradox of their existence. We must neither deny the effects of structural violence on their lives and work nor reduce their practices to these structures.51 We must respect the depth and boundlessness of their imaginations, the conceptual and emotional richness of their aesthetic propositions, while also recognizing the way such experiments often, but not always, arise from specific experiences of violence, confinement, dehumanization, and grief. To see their art, we must hold all of these things together. We must also ask ourselves what we desire from these artists—representation, resistance, heroism, education, certainty, and absolution come to mind—and how these desires further constrain them. Finally, we must wonder, as many of these artists have wondered, and continue to wonder, how to do more than reflect the world—but to change it. It is time to turn our attention to the ground on which Floor Frame sits. How deep do its bronze roots penetrate, and how might we imagine them cracking the foundation on which they rest?

Essay Summaries

The essays in Asian American Art: Pasts and Futures span the late nineteenth century to the present and include considerations of fine art, material culture, art criticism, and curatorial practice. Authors address the specific histories and experiences of artists of Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, and Indian descent. This selection is not comprehensive, and indeed we reject the idea that comprehensiveness is possible when it comes to Asian American art. Comprehensiveness implies that perfect representation is achievable, when in fact, like anything, Asian American art only becomes more unruly, expansive, and complex the more deeply one engages it. At the same time, we acknowledge that this section has limitations in scope. Although several authors take a transnational perspective, the case studies are, for the most part, United States–based. Moreover, most of the authors focus on artists from the east or west coasts. We hope that these gaps will offer a provocation and invitation to scholars by suggesting how much work remains to be done.

Z. Serena Qiu’s essay is propelled by an affectively intense moment in the archive, in which she encounters an image of a nameless Chinese American woman produced as souvenir for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Qiu uses the picture as a starting point for an investigation of what she describes as the “destructive visual curiosity” about Chinese women’s bodies in the United States, and the role of photography in the proliferation, management, description, and over-description of their images. Qiu ultimately uses the essay to explore her own desires and obligations as an art historian tasked with ascertaining certainty, concluding that her role is not to fix these women, but to “abet their ongoing escape.”

Yinshi Lerman-Tan considers the writing of Sadakichi Hartmann, who in 1901 authored the two-volume survey A History of American Art. Her critical reappraisal of Hartmann’s writing shows how his own uncertain naturalization status inflected his understanding of American in this early survey of American art. Lerman-Tan also explores the vexed question of Orientalism in his work and life, noting his recognition of its operations in the work of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, as well as his deliberate performance of Orientalist tropes, suggesting the compromises required to survive as a person of Japanese descent in the United States during the early twentieth century.

Tyrus Wong is best known as the lead animator of Bambi, but as Karen Fang shows, perhaps his richest contribution to American visual culture was his partnership with Hallmark. For nearly twenty-five years, Wong designed dozens of bestselling greeting cards for the company. Her diligent archival reconstruction reveals the extent of the popularity of the cards but also locates their broad appeal in what Christian Klein has dubbed “Cold War Orientalism.” Fang’s essay suggests the importance of commercial art—creative work that paid—to Asian American artists who might have few other options for a sustainable vocation.

The question of work is also at stake in Catherine Damman’s essay, which considers the late 1960s sculpture of Los Angeles artist Carl Cheng. His objects assume the guise of outmoded, inefficient, and ultimately useless technological gadgets, which she deftly links to contemporaneous unease about the utopian promises of technology and the racialization of Asians as “having a putatively unusual capacity for economic modernity.” In their refusal to work, Cheng’s “broken systems” thematize the empty promises of capitalist efficiency while highlighting the blindness of conventional narratives of postwar art to the intersections of labor and race.

Sadia Shirazi’s essay considers the Dialectics of Isolation, a 1980 exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery curated by artists Ana Mendieta, Kazuko Miyamoto, and Zarina. She traces the exhibition’s genesis to a special issue of the feminist magazine Heresies, which used the term “Third World Women” to signal an international coalition of women-identifying artists in direct opposition to what they described as the “white, middle-class” emphasis of United States feminism. In contrast to retrospective attempts to circumscribe the exhibition into liberal narratives of multiculturalism, Shirazi shows how Dialectics of Isolation was originally informed by decolonial perspectives.

Eunyoung Park likewise takes a transnational perspective in her essay surveying the collaborative efforts of Korean American artists in New York in the 1980s and 1990s. These artists organized exhibitions and cultural events, and they formed the SEORO Korean Cultural Network to support their efforts. Park’s attentiveness to the political and artistic contexts of both Korea and the United States allows her to tease out a nuanced picture of the questions, activities, and concerns of Korean artists who arrived in the United States during this period. She shows how contact with established Asian American cultural groups led these artists to reflect on their own position in the United States and also offered a model for collaborative artistic work and advocacy.

Three final essays examine the practices of contemporary Asian American artists grappling with history. Jenni Sorkin considers Tina Takemoto’s engagement with the archive of Jiro Onuma, a gay Japanese American man who was incarcerated at Topaz War Relocation Center. In Takemoto’s film Looking for Jiro, they imagine Onuma’s work at Topaz’s mess hall as a musical revue reminiscent of both Broadway and queer club culture, the site of Takemoto’s own drag king performances. Sorkin calls the performance “a joyful embrace of high camp as a strategy to mitigate the oppressions of camp life,” a fantastical embodiment of history that crosses normative gender and temporal structures. Takemoto’s transhistoricism locates queer desire in the closets of history not to deny the privations of incarceration but to show all that exceeds its grasp.

Ellen Tani’s essay explores the work of Filipino American artists Jerome Reyes and Maia Cruz Palileo. Both use photography and the archive, traditionally tools of racial formation and colonial management, to engage key moments in history: US warmongering and colonialism in the Philippines at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Third World Liberation Front, and the eviction of tenants from First International Hotel, or I-Hotel, a low-income, single-occupancy residential hotel in San Francisco’s Manilatown. Working across video, installation, and painting, Tani argues that these artists engage historical archives not simply to remember or preserve history but to redirect the tools of its construction.

Finally, Hsuan Hsu’s essay examines the colonial intimacies conjured by the olfactory practices of Beatrice Glow. Glow’s engagement with global luxury products such as silk, tobacco, and spices foregrounds the material exchanges engendered by entwined processes of settler colonialism, chattel slavery, and racial capitalism. Her work is therefore congruent with Lisa Lowe’s recent scholarship, as well as the transpacific and archipelagic turns in Asian American studies. Glow’s canny engagement with scent reveals the extractive colonial desire that undergirds the history of perfume, while also acknowledging the shared but uneven histories of dispossession and colonialism among Asian and Indigenous people across the Pacific.

August 10, 2022: Note 51 was updated to include a reference to David L. Eng and Shinhee Han, Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation: On the Social and Psychic Lives of Asian Americans (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019).

Cite this article: Marci Kwon, introduction to “Asian American Art, Pasts and Futures,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11446.

PDF: Kwon, introduction to Asian American Art, Past and Futures

Notes

The author is grateful to Mark Dean Johnson and Margo Machida for their feedback on this Introduction.

- Throughout this In The Round, the editors have chosen not to capitalize “east” and “west.” We made this decision to connote that “east” or “west” are relative and flexible terms, rather than fixed geographical locations. ↵

- Glenn Willumson, Iron Muse: Photographing the Transcontinental Railroad (Oakland: University of California Press, 2013). ↵

- Jennifer L. Roberts, Mirror-Travels: Robert Smithson and History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 114. ↵

- Kandice Chuh, Imagine Otherwise: On Asian Americanist Critique (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 126. ↵

- Gordon H. Chang, “A Note for History,” Amerasia Journal 45, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 4. Together with Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Chang codirected the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University. Primary documentation and other resources from this project are available at http://web.stanford.edu/group/chineserailroad/cgi-bin/website. ↵

- Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), xii. ↵

- Quoted in Gordon H. Chang, “The Chinese and the Stanfords: Nineteenth-Century America’s Fraught Relationship with the China Men,” Amerasia Journal 45, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 86–102, https://doi.org/10.1080/00447471.2019.1611344. ↵

- Chang, “The Chinese and the Stanfords,” 86–102. ↵

- Karuka, Empire’s Tracks, xiv. ↵

- “Four Special Spikes,” National Park Service website, last updated April 30, 2020 https://www.nps.gov/gosp/learn/historyculture/four-special-spikes.htm. ↵

- Gordon H. Chang, Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019), 207. ↵

- Anne Anlin Cheng, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief, Race and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 24. ↵

- Stanford University, “Uncovering the Lives of Chinese Workers Who Built Stanford,” Stanford News, April 11, 2019, https://news.stanford.edu/2019/04/11/uncovering-lives-chinese-workers-built-stanford. ↵

- Emphasis original. Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 39. ↵

- It is, in other words, a “melancholic retention,” to quote Anne Anlin Cheng, who explores the psychoanalytic dimensions of the forgetting described by Lowe. See Cheng, The Melancholy of Race, 9–10. ↵

- Cheng, The Melancholy of Race, 4–5. ↵

- As Viet Thanh Nguyen observed of Asian American literature: “The way critics have tended to read this literature, as cultural works that demonstrate resistance or accommodation to racist, sexist, and capitalist exploitation of Asian immigrants and Asian Americans, may be as much a reflection of the critics’ professional histories, political priorities, and institutional locations as what may be found in historically framed close readings of the works themselves.” Viet Thanh Nguyen, Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 3–4. ↵

- Elaine Kim, “Interstitial Subjects: Asian American Visual Art As a Site for New Cultural Conversations,” in Fresh Talk, Daring Gazes : Conversations on Asian American Art, ed. Elaine H. Kim, Margo Machida, and Sharon Mizota (Oakland: University of California Press, 2003). ↵

- Gordon Chang, “Foreword: Emerging from the Shadows, The Visual Arts and Asian American History,” in Asian American Art: A History, 1850–1970, ed. Gordon H. Chang, Mark Johnson, and Paul Karlstrom (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), xii. ↵

- Chang, “Foreword,” x. ↵

- Kim, “Interstitial Subjects,” 4. ↵

- Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America: A History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015). ↵

- Although the Third World Liberation Front at SFSC is often described as a strike for ethnic studies, historian Gary Y. Okihiro has argued that the TWLF actually proposed a “Third World curriculum” that stressed self-determination and global anticolonial, antiracist approaches. “Ethnic studies,” which SFSC offered instead, was based on the work of sociologists at the University of Chicago, whose work “conceived of ethnicities or cultures as the way to preserve white supremacy by assimilating problem minorities into the dominant group.” Gary Y. Okihiro, Third World Studies: Theorizing Liberation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 6. ↵

- Karen L. Ishizuka, Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties (London: Verso, 2016). ↵

- Margo Machida, Storytellers of Art History, Yasmeen Siddiqui and Alpesh Patel, eds. (Bristol, UK: Intellect Press, forthcoming 2022). I am grateful to Margo Machida for sharing an advance draft of this essay with me. ↵

- In addition to her curatorial work, discussed in Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander’s conclusion to this section, Machida’s book Fresh Talk, Daring Gazes with Elaine Kim (see note 17) offered critical readings of Asian American artists by a selection of writers of color. Machida won the 2021 College Art Association Award for Excellence in Diversity. ↵

- Margo Machida, Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Artists and the Social Imaginary (Durham N.C.: Duke University Press, 2009). ↵

- Johnson to the author, January 4, 2021. ↵

- Karin Higa, “Black Art in LA: Photographs by Robert A Nakamura,” Now Dig This, ed. Kellie Jones, accessed May 1, 2021, https://hammer.ucla.edu/now-dig-this/essays/black-art-in-la. ↵

- Anthony W. Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001); Anthony W. Lee, ed., Yun Gee: Poetry, Writings, Art, Memories, Jacob Lawrence Series on American Artists (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2003); Anthony W. Lee, A Shoemaker’s Story: Being Chiefly about French Canadian Immigrants, Enterprising Photographers, Rascal Yankees, and Chinese Cobblers in a Nineteenth-Century Factory Town (Princeton, PA: Princeton University Press, 2008). ↵

- ShiPu Wang, Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011); ShiPu Wang, The Other American Moderns: Matsura, Ishigaki, Noda, Hayakawa (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017); ShiPu Wang et al., Chiura Obata: An American Modern (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018). ↵

- Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005; Chelsea Foxwell, “Crossings and Dislocations: Toshio Aoki (1854–1912), A Japanese Artist in California,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/foxwell-toshio-aoki-a-japanese-artist-in-california; and Joan Kee, “Corroborators in Arms: The Early Works of Melvin Edwards and Ron Miyashiro,” Oxford Art Journal 43, no. 1 (March 1, 2020): 49–74, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcz026. ↵

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004). ↵

- Hyun Yi Kang, Norma Alarcón, and Elaine H. Kim, eds., Writing Self, Writing Nation: A Collection of Essays on Dictée by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (Berkeley, CA: Third Woman Press, 1994); David L. Eng, Racial Castration: Managing Masculinity in Asian America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001). ↵

- Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996). ↵

- Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 86. ↵

- Scholar Mia Kang is presently working on a study of multiculturalism and the institutionalization of difference in museums and art exhibitions. ↵

- Sara Ahmed, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Roderick A. Ferguson, The Reorder of Things: The University and Its Pedagogies of Minority Difference (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012); and C. Riley Snorton and Hentyle Yapp, eds., Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020). ↵

- Melania Trump (@Flotus), “We unveiled Isamu Noguchi’s Floor Frame sculpture in the Rose Garden @WhiteHouse yesterday. The art piece is humble in scale, complements the authority of the Oval Office, & represents the important contributions of Asian American Artists.” Twitter, 2:35 p.m. EST, November 21, 2020, https://twitter.com/FLOTUS45/status/1330278669739290628. ↵

- “Melania Trump Just Had This ‘Humble’ Isamu Noguchi Sculpture Installed at the White House Rose Garden,” Artnet News, November 23, 2020, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/noguchi-sculpture-white-house-1925733. ↵

- Amy Lyford, “The Vicious Cynicism of Installing Noguchi at the White House,” Hyperallergic, December 24, 2020, https://hyperallergic.com/610031/the-vicious-cynicism-of-installing-noguchi-at-the-white-house. ↵

- Susette Min, “Refusing the Call for Recognition,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10960; and Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007). ↵

- Susette S. Min, Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art (New York: New York University Press, 2018). In making this argument, Min is following the work of Kandice Chuh, who calls for Asian American studies to become a “subjectless” discourse. Kandice Chuh, Imagine Otherwise: On Asian Americanist Critique (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 9. ↵

- “Floor Frame (1962),” website of the The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, “Artworks,” last modified May 30, 2020, https://www.noguchi.org/artworks/collection/view/floor-frame-2. ↵

- Eng, Racial Castration, 1–4. ↵

- Amy Lyford, Isamu Noguchi’s Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930–1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013). ↵

- Timothy Yu, “Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and the Impact of Theory,” in The Cambridge History of Asian American Literature, ed. Rajini Srikanth and Min Song (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015). ↵

- Cathy Park Hong has critiqued academia’s reluctance to address Cha’s rape and murder, a point that is arguably symptomatic of the predominant deconstructive impulse in Asian American studies, as well as a longstanding reluctance to address race in art history. I am grateful to John Cha, Theresa’s brother, for his wisdom and friendship. Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning (New York: Penguin Random House, 2020), 155–56. ↵

- Yu, “Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and the Impact of Theory,” 318. ↵

- As Michael Omi and Howard Winant write in their influential theory of racial formation, “Race is not something rooted in nature, something that reflects clear and discrete variations in human identity. But race is also not an illusion. While it may not be “real” in a biological sense, race is indeed real as a social category with definite social consequences.” Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), 110. ↵

- This argument is indebted to the work of Dorothy Wang, who makes a similar argument about American poetry, and David L. Eng and Shinhee Han’s engagement with the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. Wang rejects what she describes as the “either-or binary of the social versus the literary,” pointing out how these categories are indicative of the way that racialized poets are often discussed solely as “occupying the realm of the bodily, the material, the social,” while “form . . . is assumed to be the provenance of a literary acumen and culture that is unmarked but assumed to be white.” Dorothy J. Wang, Thinking Its Presence: Form, Race, and Subjectivity in Contemporary Asian American Poetry (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), 22; David L. Eng and Shinhee Han, Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation: On the Social and Psychic Lives of Asian Americans (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019). ↵

About the Author(s): Marci Kwon is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Art History, Stanford University. Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander is Assistant Curator of American Art at the Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. They are Co-Directors of the Cantor's Asian American Art Initiative.