Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract

by Philip Joseph Deloria

by Philip Joseph Deloria

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019. 430 pp.; 221 color illus. Paperback: $34.95 (ISBN: 9780295745046)

Claiming an artist for the canon of American modernism, as historian Philip J. Deloria does for Mary Sully (1896–1963), necessitates an attentiveness to terminology that avoids reinscribing the Eurocentrism embedded in the very category itself. For while modernism most simply describes the range of cultural responses to the experience of modernity, the term’s art-historical deployment has infamously excluded many non-Euro-American artists. Those barred often experience modernity differently as subjects of colonial and imperial politics. Recent scholarship cautions against the unquestioned binary approach that results between tradition and modernity, often expressed through the exclusion of the so-called native or tribal from the modern. A commitment to multiple modernisms is alternatively alert to the ways in which artists who embrace tradition (especially those disempowered by colonial regimes) and those who refuse modernist forms are in fact equal and synchronous practitioners of modernism.

Deloria’s book, Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract, turns on the idea that Sully—a Dakota Sioux artist unknown to art history until now, and the author’s great-aunt—is in fact “native to modernism” (21). She was not only a Native person exploring early twentieth-century American modernism, but also native to its very conditions of possibility. Deloria insists that modernity was not a bright marker of progress for Indigenous people, but instead, an enforced colonial state of being. There was no choice but to be native—in a doubled sense—to modernity, for autochthony granted presence but not belonging. The modern was necessarily conceived in opposition to the so-called premodern native foil. But, more than a precondition for or antithesis to modernity, the disavowed native was simultaneously embraced through an enduring primitivist nostalgia for native life. It was this demand that enabled the first Native American modernists, among them the Kiowa Six and Awa Tsireh, to gain traction in the art market.1 These artists found success within the limitations of white patrons’ expectations of what Indian art should look like through formal education and patronage networks under those such as Elizabeth Willis DeHuff’s private tutorship in Santa Fe and the advocacy of Oscar Jacobson in Oklahoma. Free from the constraints imposed by the settler-colonial marketplace (but also from the attendant advantages), Mary Sully’s long-unseen work offers an opportunity to consider an alternative progression of Native American modernism—one Deloria argues is antiprimitivist in its formal preoccupation with Indian futures.

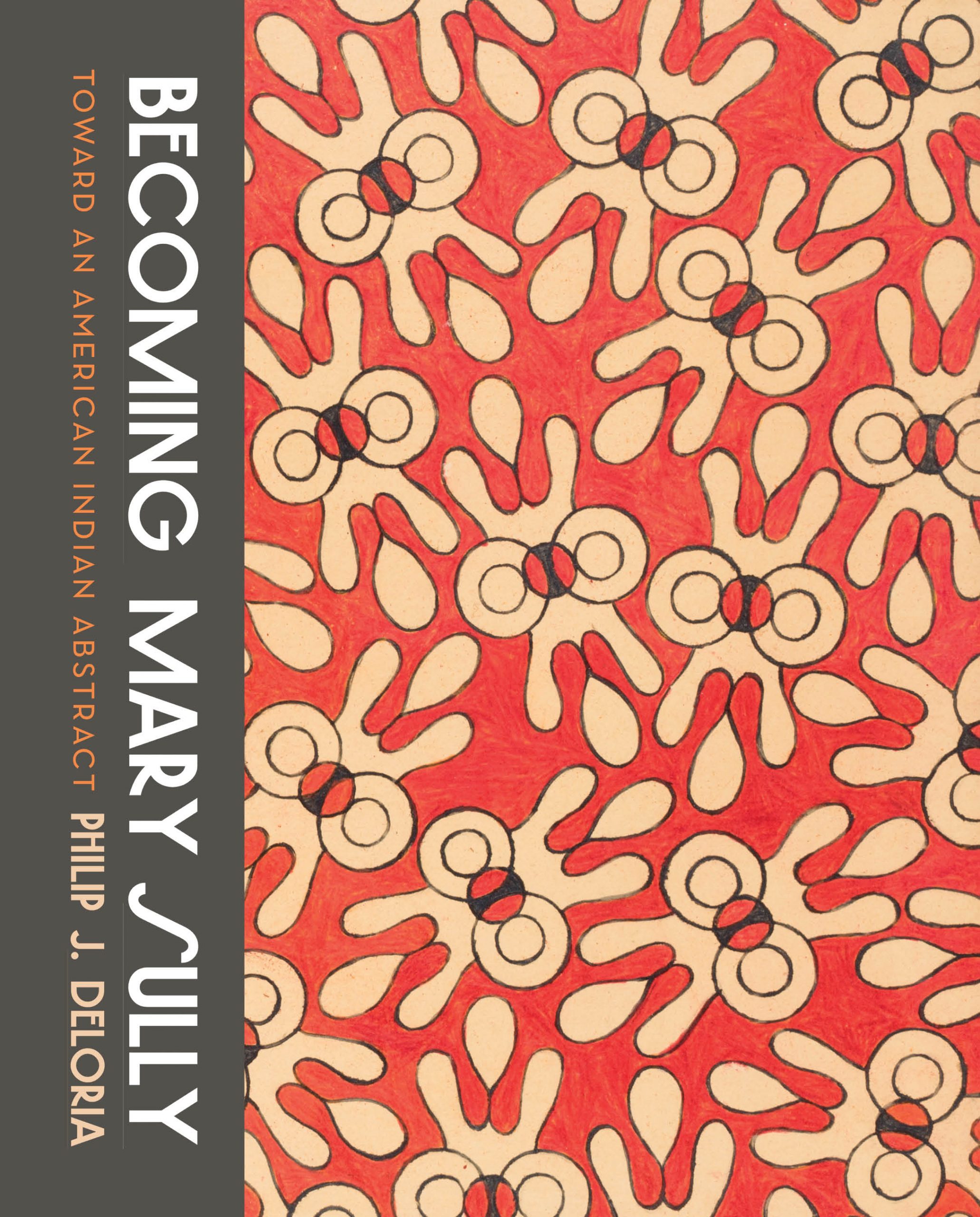

Beginning in the late 1920s, with her largest output in the 1930s, Sully completed 134 sets of what she called personality prints. Drawn in colored pencil or graphite on paper of idiosyncratic sizes, these triptychs take as their subject contemporary celebrity figures, ranging from baseball star Babe Ruth and literary icon Gertrude Stein to the South Dakota Episcopal church leader, Bishop Hare.2 Sully’s preoccupation with celebrity was in step with that of her more conventionally successful peers—among them Marius de Zayas, Francis Picabia, and Charles Demuth—who engaged with an American modernity that encompassed celebrity, machinery, advertising, and popular culture.

Sully’s work was largely unknown outside the Deloria family. While intended for widespread consumption in the art market, Sully’s drawings were exhibited only sporadically in small venues such as vocational and Indian schools in South Dakota and Minnesota. Taped together with the name of the inspiring personality affixed to the bottom of the three drawings, Sully’s work was displayed as a collection in these venues where her sister and companion, anthropologist Ella Deloria, would contribute lectures on the content of the images and their relationship to Sioux life. Deloria was a lifelong advocate and financial lifeline for her sister, seeking patronage for Sully under New Deal initiatives and from artists whom she contacted under the guise of seeking advice on her sister’s behalf. Sully also indirectly sought patronage from at least one personality print subject when she wrote to actress ZaSu Pitts asking permission to use her name under an image. While these attempts to enter the patronized art world proved unsuccessful, Sully’s project, begun first in South Dakota, continued in Kansas and New York City as she traveled with her sister, who later inherited a box containing the personality prints upon Sully’s death in 1963. The drawings have since passed through the family with little attention until recently. In 2019, three of Sully’s triptychs were professionally mounted and exhibited in the landmark exhibition Hearts of Our People: Native American Women Artists at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Despite her own anonymity, Sully’s preferred celebrity subject matter, and her artistic alias (she was born Susan Deloria) positioned her within the artistic lineage of her family. Sully’s maternal grandfather, Alfred Sully, was an amateur soldier-artist whose father, Thomas Sully, was an accomplished portraitist who immortalized the likeness of Andrew Jackson later used for the twenty-dollar bill. Deloria nonetheless begins his text with an outlier from Sully’s oeuvre that shares similar physical dimensions to the personality prints but takes a collective instead of an individual subject. A triptych titled by Sully, The Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present (after 1938; author’s collection) offers a center around which Deloria’s analysis of Sully’s artistic career, innovations, personality, and cultural milieu orbit. As a means of understanding this object, Deloria presents three paired and themed sets of chapters that progress through interwoven biographies of Sully’s person and family (Becoming); her creative formation (Reading); and the cultural, psychological and political moment in which she worked (Realizing). Personality prints are interspersed throughout the chapters, illustrating Sully’s biography, which in turn illuminates the prints’ formal or representational content.

In chapter one, for instance, quilled moccasins depicted in the bottom panel of personality prints inspired by Indiana writer George Ade and Bobby Jones suggest Sully’s creative formation as heir to traditional Dakota women’s work. But they also recall a colonial story of willful miscommunication at the heart of Sully’s complex family history. In 1857, Colonel Alfred Sully sent a small picture of Sioux Indian Maidens home to his family in Philadelphia from his posting at the Fort Pierre military station in South Dakota. With his painting he included a pair of moccasins gifted to him by one of the women pictured—perhaps Pehánlútawin, who would go on to deliver their baby (Susan Deloria’s mother) alone. Sully’s letter to his family notes that he believed that the moccasins were given “with the idea of getting [him] to give them something in return,” while in fact they were more likely offered in the Dakota tradition of kinship and as a sign of a commitment he forsook (30). Chapter two similarly begins with a personality print dedicated to Dorothea Brande, the writer of the self-help book Wake Up and Live (1936), who (despite her proclivity for American fascism) embodies what Deloria identifies as Sully’s fascination for subjects who had undergone transformation.3 After all, Susan Deloria would undergo her own transformation into Mary Sully and would continue to attempt (if unsuccessfully) a transfiguration from pathologically shy child to successful artist.

While biography is a fascinating and crucial element in Sully’s oeuvre, the formal interpretation and contextualization of her triptychs in chapters three and four form the methodological core of Deloria’s text. Each triptych follows a series of formal patterns, from the size of the paper to their order: the top panel is shorter but wider than the one below, and the last panel is the smallest of the three. Top panels consist of semiotically rich abstractions engaged with modernist aesthetics such as Surrealism, Cubism, and spatial-temporal experimentations. The top panel for Helen (Kane) and Betty (Boop) (n.d., Author’s collection), for example, gestures to the bubbly, baby-voiced Betty Boop character that Kane inspired and her many bubble bath sequences through a series of brightly colored half and full circles. Sully’s middle panels distill these colors and shapes into geometric abstractions that reveal her skills as a designer and place her in conversation with the Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau, commercial wallpaper, and textile patterns. The bottom panels are where Deloria locates Sully’s transition in the direction of American Indian abstraction. While only some bear explicit reference to Indigenous imagery—whether moccasins or ethnographic illustrations drawn for her sister—almost all share a connection to a Plains Indian tradition of women’s geometric abstraction. Among the Dakota and other Indigenous communities on the Plains, representational drawing was traditionally reserved for men while women symbolized their knowledge through geometry. Porcupine quills—dyed, flattened, and stitched onto hide with sinew thread—were among the earliest media used for such creations. Sully’s third panels frequently reference such quillwork, as well as the geometric paintings that adorned storage boxes called parfleches.

Form undergoes a transformation across the three panels of each personality print as perspective shifts and instability abounds. An important element in Sully’s life, transformation is also key to Dakota epistemology, in which “the idea that the essential quality of a thing can take on multiple forms” is central (136). While the transformations celebrated by the aforementioned Dorothea Brande were unidirectional, Dakota conceptions of transfiguration are varied and multidirectional. Deloria does not take for granted his own assumption of directionality in calling the panels first, second, and third in a proposed orientation from top to bottom. It is, of course, possible that the Indian panels are meant to be read first. Such a reading enacts a familiar narrative of assimilative social evolution, as the patterns move progressively away from Indigenous traditions toward modern white America. Deloria’s interpretive framework compellingly resists such a reading, arguing that the personality prints ask viewers to perceive the bold shapes and strong lines of the top panels before following the distillation of form on a continuum “from representation to symbolization to abstraction” (143). The perceptual cues of the drawings insist on a sequence that locates the Indian at the future-oriented end of the series rather than the beginning. In other words, Mary Sully’s oeuvre approaches an antiprimitivist American Indian abstraction that encompasses but extends beyond American modernism. Take, for example, Sully’s transformation of the grid—a leitmotif for modernist explorations of form—into a series of diamonds, a shape central to Dakota women’s arts. Sully collapses arbitrary divisions (and indeed temporal ordering) held by her contemporaries between the Native and the modern.

The role Sully ascribed to women and their work in her commitment to Indigenous futurisms may have also inspired her sister, Ella Deloria, who collaborated with psychologist Otto Klineberg on an intelligence-testing project based on the ability to remember and reproduce the abstract geometries of Dakota beadwork patterns. Chapter five considers such connections between Sully and early twentieth-century psychological and anthropological thinking. It also examines whether Sully’s preoccupation with color, shape, and musical forms may indicate her own synesthetic experience of the world.

Chapter six returns to Sully’s Three Stages of Indian History (after 1938, author’s collection) Deloria concludes that the work functions as a representation of the politics of social evolution and assimilation that Sully’s oeuvre formally rejects. The top panel represents the intergenerational trauma that haunts the modern present, including an ominous set of barbed-wire fences. The final panel shifts the geometry of the barbed wire into brightly colored diamond shapes that foretell an unbound Indian future.

Careful to avoid the reification and universalization of modernity as a Western temporality, Deloria’s explorations of Sully’s artistic modernism reveal a form constituted with and by Native American aesthetics. Through its dynamic engagement with representation, symbolism, and abstraction, Sully’s oeuvre embodies an “antiprimitivist Indian modernism” that insists on complexity over simplicity and a deliberate futurity over stasis (234). Still, Mary Sully is what Deloria calls an impossible subject for her ill fit within any creative school. Hers is a narrative of American Indian art different from the canonized story centered in places such as the Southwest and Oklahoma where formal arts education, tourism markets, and patronage coalesced and led to success for a number of Native American artists in the early to mid-twentieth century. That Sully’s work remained unseen for so long compels a reevaluation of this narrative and also suggests the potential to perceive a “visible cohort” of other American Indian women artists working within the same contexts of “Indigenous cultural continuity and futurity” (279). Moreover, unrestrained by settler demands on Indian art, Sully’s oeuvre invites a reconsideration of the boundaries of American and American Indian art.

A historian by trade, Philip Deloria’s impressive first venture into art history continues his preoccupation with how Indigenous presence throughout American history undermines codified myths of primitivism and disappearance. Deloria adeptly situates Sully within her historical context; however, biographical particulars occasionally detract from the opportunity to place his rich formal analyses of her oeuvre into deeper dialogue with her more successful Indigenous contemporaries. Given his preoccupation with the futurity of Sully’s work, Deloria’s text would benefit from a more thorough interaction with how her contemporaries failed to represent antiprimitivist Indigenous futures. Nevertheless, like the figures discussed in his Indians in Unexpected Places (2004), Mary Sully’s presence as a pioneering modernist is unexpected—but only because ongoing settler-colonialism and unexamined assumptions of American art history allow her to be so.4 Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract is a text of unparalleled importance for its introduction of a remarkably innovative artist and also for its critical engagement with and rethinking of twentieth-century American art from the perspective of one of the excluded.

Cite this article: Manon Gaudet, review of Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract, by Philip Joseph Deloria, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10762.

PDF: Gaudet, review of Becoming Mary Sully

Notes

- Deloria’s book is the first on Mary Sully, whose existing drawings are in a private family collection. Nevertheless, Deloria is in dialogue with art historians like W. Jackson Rushing, Bill Anthes, J. J. Brody, and Lydia Wyckoff who have contributed pioneering and field-defining texts on Native American modernism. While the artists featured in these histories may have been excluded from conventional narratives of American art, their work found their way into collections through systems of patronage and formal education in a way that Mary Sully’s did not. ↵

- Although they are idiosyncratic in format, the paper sizes are consistent across Sully’s personality prints. Top panel: 18 x 12 7/8 in.; middle panel: 19 x 12 in.; bottom panel: 12 x 9 1/2 in. ↵

- Dorothea Brande, Wake Up and Live (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1936). ↵

- Philip J. Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2004). ↵

About the Author(s): Manon Gaudet is a PhD student in the History of Art at Yale University