Dashing for America: Frederic Remington, National Myths, and Art Historical Narratives

A Dash for the Timber, one of Frederic Remington’s (1861–1909) largest and most characteristic works, was acquired by the collector, Amon Carter, in 1945, and hangs today in the museum bearing his name in Fort Worth, Texas (fig. 1).1 At four feet by seven feet it has an unusual immediacy and dramatic presence. Museum visitors often come in pairs and enjoy giving each other little gifts of observation and insight. A well-dressed woman was overheard recently to observe to her companion as they paused to take it in: “Look at the horses. Great horses. That’s the sign of a great artist. One of them has been shot. I love this one.” Despite the non-sequiturs and ambiguous modifiers, this was an astute as well as enthusiastic comment about a work whose object biography illuminates central concerns and disputes in American culture from the 1880s to the present.

A Dash for the Timber (painted in 1889) was successively commissioned by a wealthy capitalist, publically admired, sold to a consortium of businessmen, given to a university, deaccessioned, acquired by a prominent collector and given pride of place in his public museum. The vicissitudes of its ownership and the artist’s reputation offer a narrative about powerful (and contradictory) forces within American culture. Its original celebrity was a function of both its modernism (the scientific analysis of motion at its core) and its anti-modernism (the endorsement of an archaic model of masculinity). Its disparate reception over time sheds light on not only the work, but more important, on Remington’s audiences, on the discipline of art history, and on American culture writ large.

Helter-Skelter

Eight mounted cowboys and a packhorse gallop frantically toward the picture plane. Three riders shoot over their shoulders at a large band of pursuing mounted Indians. The title, A Dash for the Timber, suggests the possibility of escape within the thickets of a forest behind the viewer’s position, represented within the painting by a small stand of trees on the extreme left. A cloudless blue sky above and purple-blue shadows below heighten the vividness of hard orange-peach ground that dusts up white behind the cavalcade and marks the divots where bullets hit the ground. This painting is noisy with implied sound: the clatter of thirty-six shod hooves on hard pebbled earth, the “pock-pock” of rifle reports, the rhythmic metallic “clank” of kitchen gear slapping down on the back of the pack horse, the creak of leather under strain, heavy breathing of animals and men, and the distant whoop of Indians in hard pursuit. We can taste the dust, feel the sun’s heat, and respond with an adrenaline rush to this frantic cavalry charge that is a retreat.

The sense of anxiety, even terror, incited by this scene is located in the wide-eyed, pell-mell careen of the horses and our own sense of vulnerability to the chaos flying at us—no mere observers, “we” are cast as potential tramplees in this emerging narrative.2 In contrast to the horses with their nostrils flared to suck in air, eyes wide with alarm, and muscles straining, the cowboys are calm, deliberate, almost Apollonian in this seemingly desperate pantomime of equine helter-skelter.

The drama is legible to us as we understand (even if we abhor) the will-to-kill and will-to-survive evident in ferocious aggression and desperate flight. Why, we must ask ourselves, does Remington select for what he termed a “big order for a cowboy picture,” the specter of flight, even possible defeat, on the part of the category of men he so clearly admired and celebrated in the majority of his works?3 Certainly it was not to show the Native Americans as vindicated injured parties extracting just revenge for decades of incursions—he has portrayed them at the extreme right as an almost indistinguishable mass, as a generic danger balanced by and opposed to the sheltering trees on the left. These furious pursuers have adopted the rifles, horses, and bridles of the invaders, but offer no other hints of intercultural exchange, negotiation, or even human reason.

The selection of this subject, one in which the Native Americans have inverted power relations, had, rather, both a theoretical and an instructive basis. Remington clearly understood the theory of the Sublime, that is, the proposition that humans find terror pleasurable when presented at a safe aesthetic distance.4 He understood the shock this painting would give viewers, especially at this scale, that that shock would grab our attention, that we would respond somatically with both heightened curiosity and anxiety, and that we would translate that fear into pleasure. As the well-dressed museum visitor put it, “I love this painting.”

Second, the composition is designed to highlight a key quality that Remington and others in his generation attributed to and admired in the cowboys, who are, in every sense, the subject of this picture. The areas of brightest value in this tableau are the white blaze on the face of the second horse from the left, and the left shoulder of the white horse, bringing our eyes quickly to a central drama of fraternal compassion and generosity within the larger narrative of anxious flight and murderous pursuit. As the museum visitor observed, “one of them has been shot.” A buddy of the wounded cowboy, whose own horse has been grazed by a bullet, leans over to support his stricken comrade, while on the other side, his fellow takes the reins to guide this injured man’s horse toward safety. These two do not shoot but, allowing themselves to be vulnerable, attend to their stricken brother.

All of this activity is portrayed with seemingly spontaneous brushwork describing sky, ground, and Native Americans, but Remington uses much more controlled, focused, less visible brushstrokes—made with finer-bristled brushes—in depicting the central group, the horses, equipment, and faces of the cowboys. He wants us to see and appreciate all the nuances of clothing, mount, and character. One appears Hispanic, another wears the flat-brimmed hat suggestive of ex-cavalry, and the two on the left have no facial hair, perhaps indicating extreme youth.

Remington painted this picture in 1889, at the age of twenty-eight. Born in New York State, he had gone West to Montana as a teenager and experimented in his early twenties with cattle ranching, mining, sheep ranching, a hardware business, and a saloon, mostly in Kansas.5 He returned East and embarked on a career as an illustrator specializing in Western subjects and found success by 1886 at age twenty-five when Harper’s Weekly sent him to Arizona to cover the United States cavalry’s pursuit of Geronimo.6 With little more than three semesters of art training at Yale University, and three months at the Art Students League in New York City, he mastered figure drawing, composition, and the anatomy of the horse, so he was clearly a quick study.7 More important, he understood the meaning of the West to Eastern audiences.

What cultural work did this painting do for its original New York audience? Above all, it—and the body of Remington’s work as it developed in the last decade of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century—elaborated on the mythic figure of the cowboy, on his counterpart, the mythic Native American, and on the psychological uses of the West to Eastern audiences.8 This appetite for Western subject matter can be gauged by the eagerness of the editors of New York-based Harper’s Weekly, the largest-circulation journal in the country, to put Remington on contract for a princely annual stipend of $8,000 the year he painted A Dash for the Timber and exhibited it in New York. “The picture at the [1889] Autumn exhibition of the [National] Academy of Design before which stands the largest number of people,” reported the New York Times, “is Frederic Remington’s Dash for the Timber.”9 The approbation of elite audiences (such as that at the National Academy of Design, and William Dean Howells who spoke of Remington as “a wonder”) signal the appeal of Remington’s works to the cognoscenti, while the Harper’s contract testifies to his equally strong popular following in the 1880s.10

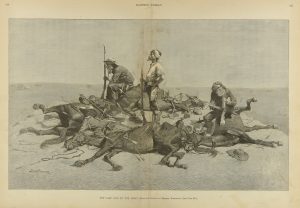

Five further Remington works were selected for exhibition at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in that same banner year, 1889, and one, Last Lull in the Fight was awarded a silver medal, testifying to international enthusiasm on the part of discriminating highbrow European judges for Remington’s work (fig. 2).11 Six years later, over one hundred of his works—mostly drawings—were exhibited and sold at the American Art Association in New York, realizing $5,800 in a single evening.12

Central to Remington’s youthful celebrity was the popular ethos attributed to the cowboy and to his niche habitat, the Open Range. Generally understood to comprise the vast public lands of Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Montana, and Wyoming, the Open Range was not only a spatial phenomena, it was, importantly, temporal, extending from 1866—when the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company in Chicago opened its integrated railroad, livestock yards, and commodities market—to the winter of 1886 to 1887 when extraordinary storms and extreme cold killed the herds and collapsed this profitable economy.13 During its twenty-year history, the Open Range permitted and encouraged Texas cattlemen and their backers, often consortiums of Eastern and foreign investors, to fatten steers on the extensive unfenced grasslands, and drive them to railheads at Abilene, Wichita, Cheyenne, and Dodge City where they were shipped East through Chicago for slaughter and consumption in the nation’s prosperous beef-eating urban centers.14 The cowboy was instrumental in this multimillion-dollar-a-year industry in which, as historian William Cronon puts it, “the logic of capital . . . remade . . . nature and bound together far-flung places to produce a profound new integration of biological space and market,” a market controlled by a powerful oligopoly of four Chicago meat packers.15 By 1889, the nation was a complex intertwined web of highly-capitalized railroads, corporations, and communications systems (and none were more tightly-centralized than the beef industry) evidencing powerful links between East and West in terms of art and ideology as well as tenderloin.

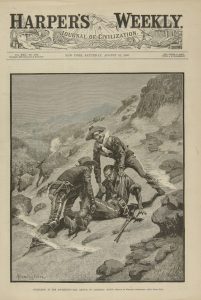

Charged with rounding up, branding, neutering, and moving vast herds over distances as long as five hundred miles, the cowboy in popular culture appropriately stood for independence, self-reliance, initiative, resilience, versatility, perseverance, and mastery of not only cattle, but also the cowboy’s primary asset and ally: the horse.16 He was also, necessarily, skilled with weaponry, and in interpreting widely varied landscapes. But cattle chaperonage is not a solo activity, so to the virtues noted above we can add teamwork and loyalty. Certainly Frederick Jackson Turner had the cowboy (as well as the fur trapper and timber cruiser) in mind when he opined in his well-known lecture at the World’s Columbian Exposition four years after Remington painted A Dash for the Timber, that the frontier had had a profound and positive effect on what he termed “American character.”17 Interestingly, although the Open Range was closed by economic failure, the proliferation of railheads, and fencing (as public lands became private property), the public perception of the cowboy changed little in the years following the invention of barbed wire in 1873, range enclosure, and the development of refrigerated railcars.18 The epic drives during which cattle drivers appeared to have expansive freedom as they operated at such a great distance from their employers were over, and cowboys became hired hands on ranches operated within the hierarchical models of all nineteenth-century businesses, a shift Remington alludes to in the title of a work about fences and gates, The Fall of the Cowboy of 1895 (fig. 3). Nevertheless, the reputation of the cowboy survived this transition intact, especially in the East. In fact, if anything, his virtues were enlarged.

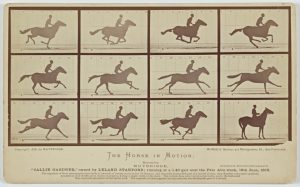

Socially, the cowboy’s identity was entwined in a world of peers in the bunkhouse and horses in the corral. Women (and the domesticity they represented) were irrelevant in the cowboy myth except, rarely, as the occasion for rescue and heroics. And we can see Remington’s consolidation of the key dimensions of this narrative: in his entire oeuvre, there are scarcely a handful of women pictured, but the horse looms large. As his friend, the novelist Owen Wister, put it in “The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher,” in which he likened the “unpolished fellow of the cattle trail” to the medieval knight, “the horse [has] been his foster-brother, his ally, his playfellow, from the tournament at Camelot to the round-up at Abilene.”19 Although Remington preferred to trace the pedigree of the cowboy to the Mexican vaqueros rather than to Wister’s European knight-errant, both views embody the same ingredients of equine romance and open-air adventure.20 In viewing A Dash for the Timber, our museum visitor had remarked to her companion: “Look at the horses. Great horses. That’s the sign of a great artist.” In Remington’s case one reason the horses are “great” is that the dynamism of the chase is described, above all, in the artist’s depiction of the horses’ legs—scarcely a hoof touches the ground in this wild gallop.

The moment in the gait that the horse’s momentum allows it to be airborne is the moment its feet are gathered under its belly, as the California photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) established in his revolutionary stop-action photographs just twelve years before A Dash for the Timber was painted (fig. 5, frame no. 3).22 Remington, in other words, gave audiences not only a more accurate picture of equine motion, but also, by selecting the moment in the stride when the majority of hooves are off the ground, a dramatically dynamic and optically revolutionary one. He wants us to believe that this phalanx is moving toward us at forty to fifty-five miles per hour, a speed that quarter horses can clock for short distances. In this regard, the painting is persuasive. When considering Remington’s debt to Muybridge, however, note that Muybridge did not photograph galloping horses from the precarious vantage point Remington gives us, but instead, safely, scientifically, from the side. Remington’s skill is then in large part, translating Muybridge’s insight into a dramatically foreshortened head-on view literally never before seen.23 This buried camera perspective is the view that in the next generation, in the new medium of films, would become a common visually arresting trope, one that startles and somatically engages observers today as vividly as it did in the 1880s.

As frantic as the horses are, and as desperate as the situation as a whole appears, Remington’s protagonists—as noted above—seem impassive. They ride and shoot with a sense of poise and confidence in their mounts and their weapons. This sense of mastery—of the landscape, of their tools, and of their horses—is central to the myth of the cowboy. And foremost of these is their mastery of horses. In other Remington compositions, such as the bronze Bronco Buster of 1895, the cowboy—despite his lost stirrup and the frantic exertions of the untutored horse—is calm and collected; his body is as well-balanced as the horse’s is not (fig. 6). This icon of “cowboyness” celebrates dominance and the rough ways it is sometimes achieved.24 The horse—whether under protest or tractable—completes the mythic cowboy. The horse is the cowboy’s force magnifier, enabling him to move farther, faster, from a more elevated and advantageous position, for longer periods of time than are possible for humankind. And, as in the Bronco Buster—a key work to which we will return—it enables him to demonstrate mastery. The horse gives the cowboy the capacity to manage steers and, when necessary, chase or outrun quarry or enemies. Without his mount, the cowpuncher is pedestrian.

Next to his horse in importance, the cowboy needed his fellows to achieve his identity and his tasks. A Dash for the Timber is as much about buddyship and mutual dependence as it is about mastery of the horse. The heroics of the situation Remington has imagined focus on the group as a group, with the stakes underlined in the efforts of two to save their wounded comrade, a theme Remington returned to explicitly in his second bronze, The Wounded Bunkie, and one he referenced implicitly in several of other media including The Rescue of Corporal Scott, a wood engraving published on the cover of Harper’s Weekly, August 21, 1886 (figs. 7 and 8).25 These are men, these paintings, prints, and sculptures argue, who depend on each other and have a deep sense of loyalty to each other.

Exhibited in the same foyer at the Amon Carter Museum as A Dash for the Timber, Coming Through the Rye (1902) reenacts in bronze the fraternal airborne gallop of a group of cowboys, but this time the careen is not about flight but about fun and fellowship as the horsemen fire pistols in the air and—in their multiple parallel gestures—express identity and brotherhood (fig. 9).26 The title is borrowed from that of Robert Burns’ 1782 poem about stealing kisses on a country footpath, a rather different sort of social pleasure than that suggested by Remington’s wildly cavorting quartet of cowboys. Perhaps we are to imagine them singing the song version of the poem, or the “rye” of the title references one of the six-foot high wild grasses of the eastern prairie. Most likely, the selection of this title suggests the alienation of these Open Range denizens from the sedentary husbandry of those who raise rye and other rooted-in-the earth grains, that is, farmers who define property as fixed land, buildings, and crops rather than as mobile gear, horses, and cattle. Generally horsemen would never trample crops, but the suggestion in the title that these men do, prompts us to understand them to be either too inebriated to know, or too contemptuous of the farmers whose labor and livelihood are damaged to care. “Cowboy,” then, is a term that embraces not only socially-endorsed virtues (such as resourcefulness and loyalty) but also some “wild,” “untamed,” transgressive behaviors that mark them as undomesticated bachelors.27

More ambiguous than the cowboy is the fin de siècle mythic Native American. Almost invariably figured male, Remington’s Indian is by turns noble savage (wise about nature, stoic about pain, honorable), a member of a poignantly mourned “dying race,” or, as in the case of A Dash for the Timber, savage primitive bent on mayhem and destruction. In this work, the Native American group is figured simply as a demonic force, the cause of the uproar in the foreground, and foil for the cohort of calm, exemplary cowboys selflessly looking after a wounded comrade. The year after he painted A Dash for the Timber, Remington suggested harnessing the energy and skills of Native American men into organized “mounted regiments,” that “under the Cossack organization, [might become] a semi-industrial military class” with the same pay and rations as regular soldiers.28 Such a proposal suggests a dignified functional synthesis in the artist’s imagination, of “noble savage” with controlled “savage savage,” culturally and economically integrated into the dominant culture. This project to militarize the Indian was one of many solutions proposed to remedy, in Remington’s words, “the whole problem of what to do with 250,000 [conquered] people of both sexes and all ages . . . a step toward complete civilization and American citizenship.”29

Ironically, at the same time, forces in mainstream culture moved to employ elements of traditional Native American life to de-civilize urban middle class and elite boys who were felt to be in need of relief from the (feminized) domestic culture of their homes. From the 1880s, summer camps—focused on canoeing, teepees, council fires, archery, and feathered headdresses—were successfully established, especially in the rural areas of the Northeast to counter their “soft effeminate home life” with summer episodes of “robust, manly, self-reliant boyhood.”30 It is notable that these camps tended to be themed and named after Indians,— understood to exhibit more primitive, elemental forms of masculinity appropriate for boys—rather than cowboys. (For adult fin de siècle males the cowpuncher provided the more appropriate and credible model.) The eclectic assemblage of cultural markers of Indianness used in the context of boyhood camps to foster physical and moral hardiness was drawn in part from Indian accoutrements and activities seen at the traveling Wild West shows where Native Americans impersonated themselves in popular tableaux and reenactments.31 Remington’s Indians were seen by their late-nineteenth-century audiences within the context of these many understandings—and misunderstandings—of Indianness. In fact, his five paintings exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in 1889 would have been understood by Parisians within the context of the popular Buffalo Bill Wild West performances taking place daily nearby.32

Urban Cowboys

Remington’s paintings (and Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West reenactments) help us understand the visceral appeal of the cowboy ethos by making concrete and immediate personal and social qualities that are abstract, qualities that (male) audiences in urban centers in the United States and Europe found useful or admirable. Those invisible valued personal qualities with which the myth of the cowboy (and to a certain extent the Indian) endowed its subjects—independence, self-reliance, skill, perseverance, self-sacrificing loyalty—were externalized with physical accoutrements, exotic landscapes, and pantomime enactments representing a seemingly simpler world of noble manual labor and military prowess. They represented anti-modernism in a world increasingly troubled by the physical and psychological dislocations of modern life, especially as these complexities—in all social classes—impacted men.33 In the late nineteenth century, men suffering from a nervous disorder thought to be brought on by urbanism and the pressures of modern life were diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia, the standard treatment for which involved sending the patient away from the city and into hyper-masculine environments.34 Thomas Eakins (1844–1916), for instance, suffering from depression in the wake of his dismissal as director of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1886, was advised to go West, not to rest but to engage in the vigorous activities of cowboys. His sojourn in the summer and fall of 1887 resulted in several paintings of Western subjects, among them Cowboys in the Badlands of 1888 (fig. 10).35 Reinvigorated there, he wrote home to his wife admiringlyof watching the physically skillful men in this environment: “The [former] Indian fighter made a beautiful sight riding on his old Indian war horse. It was as pretty riding as I ever saw. The old horse had a long regular swing up hill & down & over broken places & creeks & the man swung on him so easy & graceful he looked like a part of the horse.”36 Eakins returned home to Philadelphia with three guns, buckskin clothing, and two horses. He soon produced Cowboys in the Badlands in his Philadelphia studio, a painting in the same genre as A Dash for the Timber (although one in a more contemplative mode), namely, a work constructed to describe and explain the West to an audience in the East.37 Others travelled to the closer but no less rugged and masculine environment of the Adirondack Mountains in Upstate New York to hunt game and to fish, and live in lean-tos or elaborated log cabins known as camps. Winslow Homer (1836–1910), who preceded Remington as a Harper’s Weekly artist (in the decades of the 1860s and 1870s), vigorously embraced life in the woods, drawing and painting forest guides, hunters, and timber cruisers for Harper’s large urban audiences, and for the successful businessmen who spent summers in the woods (or wished they did), and who bought his paintings (fig. 11).

What I am suggesting here is that artists such as Remington and Homer gained traction with audiences of all kinds by holding up to armchair readers of Harper’s models of rustic masculinity liberated from the competition of the modern workplace, the cacophony and confusion of the city, and perhaps most important, the trammels of domesticity and the complexities of dealing with women. Homer’s and Remington’s men are exaggeratedly male, exceptional at mastering the wide expanses of unowned and unfenced nature that was their province, where they enjoyed (or appeared to enjoy) extraordinary freedoms and powers. What these artists offered to audiences in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Paris, was a set of recognizable enabling myths with bold surrogates, allowing urbanites adventures by proxy, and in many cases, violence by proxy. Cowboys, timber cruisers, and wilderness guides, they proposed, were not only good to experience firsthand, they were also good to think, both for the middle class subscribers to Harper’s, and the elite purchasers of Homer, Eakins, and Remington paintings.

Remington’s life’s work, then, could be seen as a mission to bring the West east, to help cure modernity’s dislocations with what Michael Kimmel calls “useful fictions.”38 His paintings represent both “once upon a time” and “time present.” In 1889 as noted above, he exhibited A Dash for the Timber at the National Academy of Design and received enthusiastic reviews.39 That same year he secured steady employment with Harper’s (they published more than one hundred of his illustrations in 1890), and bought a substantial property in New Rochelle, joining the first wave of out-migration to the suburbs.40

A Dash for the Timber had been commissioned by Edmund Cogswell Converse, who specified a work that would document a life-and-death struggle on the frontier; it was exhibited as his property in 1890.41 Characteristic of Remington’s known patrons, in 1890, Converse was a forty-year-old capitalist involved in the steel industry in western Pennsylvania; subsequently he became an associate of J. P. Morgan, and a major New York banker and financier.42 His obituary in the New York Times mentions that in 1912, he purchased a portrait by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) “of Count Rumford, from whom he was descended” for $75,000 (fig. 12).43 It is tempting to see these two acquisitions as alternative pedigrees and models for an ambitious and successful businessman. Converse’s enthusiasm for Remington’s painting (and for cowboys) was apparently short-lived. We can surmise that although the painting depicts a “life and death struggle,” as prescribed, its drama of selfless buddyship was insufficient to offset its depiction of retreat and suggestion of defeat for the relentlessly successful Converse. In 1893, A Dash for the Timber was on display at the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall Fair where it was bought by a group of local businessmen and given to Washington University in that city, opening a new chapter in the biography of this painting.44

“Undesirables”

Often celebrated as the “Gateway to the West” because of its role in the transcontinental trek of explorers and migrants westward, St. Louis was an apt home for a work dramatizing the West for Eastern audiences. The art collections of Washington University were already a decade old when this major work was given to the institution. A half-century later, this painting, embodying so much about antimodernism and mythic masculinities in Gilded Age America, faced triumphant modernism and its very different myths about virtue, purity, and manly ideals, as well as hardening distinctions between elite and popular culture. In 1941, a young Swedish-German émigré art historian, Horst W. Janson (1913–1982), joined the faculty of Washington University, bringing a very European-oriented modernist view of the development of art to the institution.

Eventually rising to the top of the profession, Janson would move on to New York University in 1949 and write the discipline’s most influential mid-century textbook.45 But even in his twenties, Janson had confidence and authority. Although he became a citizen in 1943, there is little indication in the record that he had interest in or regard for American art. Moreover, his view of the history of art tended to decouple artistic creativity from culture, focusing instead on formal qualities of individual works and on generational evolutions of artist-to-artist transmission of aesthetic ideas. His overall model for understanding art privileged innovation within tradition and hung its narrative on a teleological armature in which the development of European modernism was the supreme inevitable achievement of Western art. In 1981, looking back on the decisions he made as curator of the Washington University art collection forty years earlier, Janson put the situation this way:

Between 1881 and 1945, there was no screening committee that decided whether a given work of art. . . was suitable for a university art collection. . . .so we fell heir to [a] herd of beer steins. . .[and a] large collection of English nineteenth-century china. . . .There were [also] a lot of paintings. . . .[The] acting director of the [St. Louis] City Art Museum told me that they were planning to kind of weed out the holdings of. . .[that] Museum. . . [to] sell off things that they regarded as not wholly desirable—or maybe below the [appropriate] standard. . . .I seized the opportunity and persuaded the University administration that we ought to join into this action and sell [our]. . .undesirables. . .and thus accumulate a fund from which we might purchase. . .twentieth-century [European] art.46

Here in retrospect, Janson associates A Dash for the Timber—which headed his deaccessioning list—with “a herd” of beer steins, miscellaneous chinaware, and nameless paintings in the category of “undesirables.”

The Washington University sale brought $40,000 of which the Remington painting generated $23,000, and with which Janson bought second-tier works by Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Paul Klee, and other European modernists, commendable, he notes, because of their “redefinition of pictorial space,” that is, because of their formal characteristics, and their technical novelty (fig. 13).47 His explanation for the deaccessioning of A Dash of the Timber—which provided the lion’s share of funds for his modernist shopping spree—is interesting:

I never did think of Mr. Remington as a genuine western artist. (My skepticism was borne out when we moved to New York in 1949, because it so happened that we bought a house in New Rochelle. . . practically next door to the Remington “ranch.” That is where he lived and that is where he painted his western pictures.) He is still very much in fashion among Oklahoma oil millionaires. . .but in terms of the development of twentieth-century art, his significance [was then negligible and] has not increased over the past thirty years.48

Janson bases his disdain for Remington on three points: regional inauthenticity (he lived in New Rochelle, not Fort Worth), a dismissible community of admiration (Oklahoma oil millionaires), and lack of participation in the narrative of the development of twentieth-century European modernism about which Janson was professionally knowledgeable and in which he was professionally invested. Of these, most peculiar is the presumed requirement that an artist’s subject matter “match” his upbringing and residence to be “genuine.” This is a yardstick he does not apply to European artists. Of Orientalist painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), for instance, he reports in his influential textbook with approbation “he was enchanted by a visit to North Africa in 1832, finding there a living counterpart of the violent, chivalric, and picturesque past evoked in Romantic literature. His sketches from this trip supplied him with a large repertory of subjects for the rest of his life—harem interiors, street scenes, lion hunts,” for his Paris patrons, such as Lion Hunt of 1860 (fig. 14).49 But Janson saw Remington as a Western artist, not an artist of Western subjects, and thus believed he should express regionalism in his street address as in his works. Janson most likely believed Remington’s project to be documentary (and certainly we know Remington labored, for instance, to acquire a variety of worn chaps to make sure his cowboys’ clothing in A Dash of the Timber was congruent with contemporary working equipage).50 But as I have argued, Remington was painting and sculpting imaginative tableaux like any other genre painter, with a consciousness of widely-circulated ideas, ideologies, and myths about cowboys and their activities. As in the case of Delacroix’s Arabs, or Paul Gauguin’s (1848–1903) Breton peasants or Tahitians, the object was to capture situations, figures, and costumes that would be legible to urban audiences as culturally different but also as replete with ideological freight useful in distant Paris. But Janson did not see inconsistency in requiring what he called “genuineness” in an American artist that he did not require in a European.

Second, he exposes a regional snobbism in that snarky comment about oil millionaires and his implied subtext that Europeans are knowledgeable about art and values while Western nouveaux riches are necessarily uneducated in their tastes and do not understand art values. Nevertheless, he profited from the willingness of multiple individuals and institutions as they bid up this work to $23,000 and secured his war chest; he had good reason to thank the bidders rather than disparage them.51

Janson was a tastemaker but he was also swimming comfortably on a major art historical tide that continues to carry much before it. His opinions and his actions concerning Remington’s paintings in general, and A Dash for the Timber in particular, point to a pair of polarized views—this, Janson’s, in which the artist is seen as inauthentic and his works, encoding an ideology of heroicism, are superficial and “undesirable”; and the opposite, but related, popular view that takes Remington’s art to be straightforwardly documentary, easily legible, and wholly admirable, or as one characteristically enthusiastic author put it, “Remington’s art and life show an adventurous spirit that is associated with the pioneer tradition of the untamed American West.”52 To the Janson camp, that is, those who assigned and taught his textbook through six editions, between 1962 and 2004, and endorsed his approach through the long half-century dominance of his point of view in the discipline, this bright-eyed admiration is naïve.53 Sophisticated Jansonesque viewers prefer visual subtlety and aesthetic intertextuality to pictorial “action,” and cringe at Remington’s “adventurous” narratives.54 In this collision of divergent highbrow and lowbrow readings, we see incompatible national narratives as well as competing views of Remington and aesthetic value.55

Janson’s evaluation of A Dash for the Timber in particular, and of Remington in general, signaled an important shift in opinion in the mid-twentieth century. While in the fin de siècle period Remington found ready admirers at the most discriminating venues (New York’s National Academy and the Paris Exposition Universelle, for instance) as well as in popular Harper’s, sixty years later distinctions between highbrow (or elite) and lowbrow (or popular) culture that had not been so pronounced in the earlier period had evolved into distinct (and often hostile) camps. This polarization was a matter of both art and gender ideologies. In art, the evolution of the intellectually-engaged vertical plane (a two-dimensional canvas surface treated as a two-dimensional surface) had triumphed over the long-standing authority of the somatically-experienced simulated horizontal perspectival plane that Remington so dynamically projects beyond the picture space in A Dash for the Timber. In terms of model masculinities the cowboy retained considerable ideological power in popular culture (films, country and western music, and, as we shall see, in politics), but he had decisively lost ground with the cultural elite. Perhaps hastened by such moral ambiguities as the Vietnam War, many tended to look at the cavalryman and cowboy—personifications of what were understood to be archetypal American (male) virtues—with an ironic or cynical eye. These two disparate ideological (and political) readings of Remington have persisted into the twenty-first century. Similarly, Janson’s art historical investment in a teleological framework in which value accrues in a work of art (or an artist’s oeuvre) in relation to its position in a narrative of evolving artistic avant gardes persists.

There is also a recent somewhat offbeat interpretation of Remington’s work that re-positions sophistication in the person of the critic whose recondite readings rehabilitate seemingly banal “action” paintings, transforming them into intellectually interesting visual texts described as betraying cultural motivations unintended by the artist and unrecognized by his many audiences. Alex Nemerov, for instance, argues that Remington’s oeuvre can be decoded as a series of (unbeknownst) self-incriminating displaced social and political allegories evidencing attitudes that today we deplore.56 In this reading, the issue of value is displaced from the artist, the protagonist cowboy, and his audience to be registered instead in the adroit moves of the interpreting scholar.

The view that I have been advancing here argues that Remington’s art drew on his years of living in the West to create fictive self-contained artworks that were vivid, original, and both responsive to, and evidence of, larger cultural appetites and needs among Gilded Age Eastern and urban audiences. Beyond the era of their creation, the story of the reception of his works, evidenced, for instance, in the narrative provenance of A Dash for the Timber, sheds light on the evolving character of American culture and reveals important unmended fracture lines in the wildly disparate values attributed to these works and to the populations that disparage or, in the voice of the well-turned out museum visitor, “love” them. In other words, the story is about the viewers and the irreconcilability of their views.

What art history as a humanistic discipline does, on the one hand, is the analysis of individual works or sets of works, and on the other, establish or reestablish the “art historical significance” of an artist or a work by means of persuasive readings.57 The overall project is to create a canon, ever-refined by consensus wisdom, of works and artists that are (more or less permanently) understood to exhibit high aesthetic value and that link to one another in a developmental sequence.58Remington troubles this paradigm. As Janson put it “in terms of the development of twentieth-century art, his significance has not increased over the past thirty years.” Remington has been virtually written out of the art historical canon and yet he continues to have a substantial following and not just among lowbrow audiences and “Oklahoma oil millionaires.”59

Presidential Cowboys

If we ask not what is Remington’s “art historical significance,” but rather what is the cultural significance of the artist’s works, his reputation, and his audiences, a rather different and more pressing narrative emerges. Literally no American artist’s works are as frequently and systematically offered up publically as representing national character and policy; this fact alone should prompt us to look attentively at what Remington is saying and to whom. During the Gerald Ford Administration, a casting of Bronco Buster was given to the White House art collection and placed in the Oval Office (fig. 6).60 This was not the first time the American presidency was associated with this Remington sculpture. Three years before he was elected president, Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders gave him an early casting of the work, which he displayed at his home (now the Sagamore Hill National Historic Site) throughout his life.61 The White House Bronco Buster has been chosen by successive presidents for prominent placement in the Oval Office during the last five decades and has been pointedly photographed in association with incumbents as disparate as George W. Bush and Barack Obama (fig. 15).62

This association between the presidency and this singular Remington work has not been lost on the public—the award-winning television series The West Wing (1999–2006) prominently displayed the Bronco Buster on the desk of fictional president Josiah Bartlet, an authenticating detail beyond any other element of setting, pointedly indicating the nature of the space, the characters, and the decisions made there. What exactly, then, does this artwork say about (as well as to) those who gaze upon it in this context? It appears that the power of this sculpture to capture its central position in United States political dramas—fictional and real—resides in its presumed and projected Americanness, its unequivocal maleness, and its association with the presumed character of “the frontier.” It encapsulates, in iconic shorthand, the story Americans tell themselves about themselves both as individuals and as an aggregate: they are skillful, cool-headed, resilient, self-reliant, tough, and most important, triumphant in the face of powerful, frenzied, and cunning adversaries. These are not the lesser virtues of teamwork and selfless generosity seen in A Dash for the Timber, or the unleashed boisterous good spirits of those riders careening through the rye, but rather, the core cowboy in focused one-on-one combat. The location of the Bronco Buster within the context of the Oval Office through eight presidencies suggests its capacity to speak to and for the incumbent, allowing key communications between the human occupants of that space to be unsaid and displaced onto this mime show of an archetypal power struggle.

As Richard Slotkin, invoking Northrop Frye and Roland Barthes, so persuasively states it, a “set of powerfully evocative and resonant ‘icons’” about the frontier function as familiar frameworks and metaphors that “connect what happens to principles that the culture has accepted as valid representations of the nature of reality, of moral and natural law, and of the vector of society’s historical destiny.” “Myth does not argue its ideology, it exemplifies it. . . .transforming secular history into a body of sacred and sanctifying legends” about “the heroic foray of civilized society into the virgin wilderness, and. . .the conquest and subjugation of wild nature and savage mankind.”63 In embracing such icons as the Bronco Buster, politicians and their constituencies are not wallowing in clichéd nostalgia about a lost era, or doggedly admiring works of no art historical significance as Remington’s critics would have it, but rather they are reading a blueprint for decisive present and future action in the real world.64

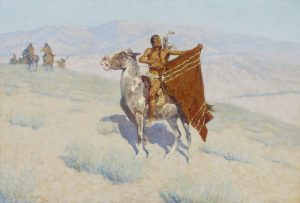

Genre paintings and sculptures are, above all, communication devices, ones that do their communicating in a mime show of costume, landscape setting, and frozen action, a central truth that Remington thematizes in his many paintings about voiceless communication. In Blanket Signal and Long Horn Cattle Sign (Amon Carter Museum of American Art), for instance, Remington underlines powerful acts of communication that do not involve spoken or written language (fig. 16).65 The human body, with gestures and props, makes meaning within the fiction of the painting and between the painting and its audience. Blanket signals, smoke signals, hand gestures, and legible pony tracks speak as eloquently as spoken language within Remington’s works and point us to this principle. Like histories, jokes, and literature, paintings are condensed stories that tell us, in our reading of them, about ourselves, our hopes, fears, and (potentially incompatible coexistant) ideologies. But the artworks carry their tales in pantomime and their meanings are unstable. Art historians tend to privilege the moment of conception, creation, and initial reception of artworks, and position their own work as the achievement of ever more accurate and more perceptive interpretations of that initial creative moment as it links diachronically to other creative acts. The object is positioned as a stable text seen evermore clearly as discoveries of data and new interpretive strategies sharpen knowledge and define it as increasingly more important as an art object within a chronological evolution of art objects. The case of Remington suggests that looking at reception through multiple generations of interpreters can position the work as something else, as a touchstone linked synchronically to successive moments, revealing shifts in culture as the object is valued, disparaged, and revalued by successive audiences, disparate social classes, and different kinds of knowledge brokers.

This is a tale, since the mid-twentieth century, of powerful but widely polarized views of Remington’s work, each eloquent of facets of American culture. The larger narrative of his reputation from 1889 to 2014 is not one of evolving or ever-sharpening understanding of his art historical importance, but rather the development of warring interpretations that each deserve our respect as evidence of disparate vernacular and scholarly views of national culture. The narratives that are the most compelling for the widest audiences demand attention, not suppression. Male Americans in the 1885 to 1910 period in which Remington flourished were not all daring, loyal, courageous, self-reliant, semi-feral hell-raisers, but these were characteristics and models sought by many readers of Harper’s and buyers of paintings. Their pleasure in viewing (and possibly identifying with) his subjects, and the continuing popularity of these images over 125 years, signal not (or not merely) the uncorrectable naivety of most Americans or their blindness to the logic of capitalism and imperialism, but rather the continuing need of Americans to explicate or assert national character and history in shorthand, useful fictions that we would be wise to read and attend to closely as United States culture’s version of Geertzian “deep play.”66

Remington, like Winslow Homer, portrayed male types engaged in lives of skilled but manual labor that businessmen then and presidents today do not seek to literally emulate—except occasionally, briefly, under controlled circumstances, in the summer months. These narratives—rendered as aesthetic wholes, obviously edited out the boredom, hardship, and penury that distanced these outdoor lives from the urban consumers of their images. But this is why we speak of the points of intersection between these disparate populations as “myths,” not because they are untrue, but because they are powerful, widely-shared, generic ideas that evidence desire, usually a desire to live a more heroic and a more exciting life in which the value of skill, labor, and community are visible and vital.

In the last years of his short career Remington radically altered the tone of his works, embracing a more contemplative, static, nocturnal view of his subjects, picturing them in flattened ambiguous foreboding space.67 These images are as eloquent of those dawning years of the twentieth century as his sun-baked action images were of the 1880s and 1890s. The point is not only that Remington had his finger firmly on the shifting aesthetic pulse of his moment but that the issue of reception has a longue durée that is as interesting and complex as the work that sparks it. The issue is not to decide whether Remington is worthy of museum walls and our attention, or parse what Remington is consciously or unconsciously up to, but to investigate how the reputation of his works—paradigmatically A Dash for the Timber and Bronco Buster—tells us about powerful (and contradictory) forces in our culture over time.

When the New York Times reviewer in 1889 described the public debut of A Dash for the Timber as “The picture at the Autumn exhibition of the [National] Academy of Design before which stands the largest number of people”—he was recording an event at which New Yorkers were learning about both the West and about themselves.68 As we brood about what captured their attention and admiration, it is important to step back and focus on the long history of the perception of that land beyond the 100th meridian, especially from the perspective of the Atlantic seaboard.69 It has been a perception colored by the reading of novels, the witnessing of Wild West entertainments, and, above all, the study of visual images of the actors, the stage, and the actions that mirrored their projected hopes about a parallel, admirable, seemingly permanent, mythic Americanness. In the elegant museum visitor’s “I love this painting,” we can catch an echo of the admiring throngs at the National Academy of Design a century earlier. And in the presidents’ daily gaze upon the Bronco Buster, we can see yet another chapter in the reception of Remington and another reason we need to take this artist seriously. A Dash for the Timber and Bronco Buster matter not just because they speak in dramatic terms about resilience and ideal manly character, but because they comment on attributes many Americans wish they could embody as individuals and as a nation. What seems key is the fact that the narrative of the journey an artwork takes through time, in the push-pull between popular and scholarly readings, is one key cultural Rorschach test we should attend to if we want to learn about the power of myths and the mechanisms by which national culture does its work.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank and acknowledge for their collegial support and helpful suggestions concerning earlier drafts of this essay: Paul Groth, Richard Hutson, Kathleen Moran, Louise Mozingo, and Christine Rosen; I am also grateful to research assistants Susan Eberhard, Cameron McKee, Mary Okin, and Kappy Mintie, students in the Berkeley Americanist Group, and the anonymous reviewers for Panorama. Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and at Yale University.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1517

PDF: Dashing for America: Frederic Remington, National Myths, and Art Historical Narratives

Notes

- Patricia Junker, Barbara McCandless, Jane Myers, John Rohrbach, and Rick Stewart, An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 2001), 9–23; Rebecca Lawton, “Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth,” American Art Review, 13, no. 6 (2001): 106; and Amy Durham, “Amon Carter: The Man and His Museum,” Cowboys and Indians, 15, no. 8 (December 2007): 161. ↵

- Although certainly unusual, this dynamic composition was not entirely novel: Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) had exhibited her Scotland For Ever!—Charge of the Greys at Waterloo (40 x 76 ½ in.) in London in 1881, a painting begun in 1877 and now in the Leeds Art Gallery. See Amon Carter Museum of American Art object file. ↵

- Peter H. Hassrick and Melissa J. Webster, Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Watercolors and Drawings, vol. 1 (Cody, WY: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1996), 165. ↵

- Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757; repr., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992). ↵

- Carter Johnson Martin, comp., 150 Years of American Art: Amon Carter Museum Collection (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1996), 21. For an historiography of Remington see Hassrick and Webster, Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 1, 37–62. ↵

- James Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest (Phoenix: Phoenix Art Museum 1992), 9, 16. ↵

- Ibid., 3, 13. ↵

- See Edward G. White, The Eastern Establishment and the Western Experience: The West of Frederic Remington, Theodore Roosevelt, and Owen Wister (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968); Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), 24; and Joni L. Kinsey, “Viewing the West: The Popular Culture of American Western Painting,” in Richard Aquila, ed., Wanted Dead or Alive: The American West in Popular Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 243–68. ↵

- “Paintings at the Academy,” New York Times, November 26, 1889, 5; Michael Edward Shapiro and Peter H. Hassrick, Frederic Remington: The Masterworks (New York: Harry N. Abrams and St. Louis Art Museum, 1988), 20. ↵

- “Remington and Russell: Timeline,” Amon Carter Museum of American Art of American Art, accessed August 27, 2015, http://www.cartermuseum.org/remington-and-russell/timeline?artist=All&narrative=All&page=5. ↵

- Peggy and Harold Samuels, Frederic Remington, A Biography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1982), 123–24, 126; Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 32; and Hassrick and Webster, Frederic Remington: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 1, 11, 12. ↵

- “American Art Association: Notable Pictures, Laces, and Porcelains,” New York Times, November 15, 1895, 5; and “American Art Association Now to Dispose of Chinese Porcelains, Enamels, Jades, and Crystals at Auction,” New York Times, November 21, 1895, 8. ↵

- Terry G. Jordan, “The Origin and Distribution of Open-Range Cattle Ranching,” Social Science Quarterly 53, no. 1 (June 1972): 113–21; and William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991), 208–11. ↵

- Jordan, “Origin and Distribution,” 113; Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 218–25, 232–47. Concerning the antiquity of long-distance cattle drives by antecedent British drovers, see W. G. Hoskins, The Making of the English Landscape (1955; repr., London: Penguin, 1985), 243-44. ↵

- Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 207–59. ↵

- For discussions of model masculinities circa 1900, see R. W. Connell, “The History of Masculinity,” Chapter 8 in Masculinities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 185–203; Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995), esp. 120–215; and Michael S. Kimmel, The History of Men: Essays on the History of American and British Masculinities (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005). ↵

- Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1893 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), 200. ↵

- Jordan, “Origin and Distribution,” 119; and Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 221, 232–37. ↵

- Owen Wister, “The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher,” originally published in Harper’s Monthly, 91 (September 1895), repr. in Robert Murray Davis, ed., Owen Wister’s West: Selected Articles (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987), 39. ↵

- Wister’s “knight” pedigree of the cowboy is the author’s, not Remington’s (who credited Mexican antecedents). See Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 65; and Samuels, Frederic Remington, A Biography, 218–20. Remington spent time in Mexico in 1893, studying and drawing vaqueros and Spanish troopers. The authority Remington gives to the vaqueros origins of his heroes, and his admiring images of these Mexican horsemen, appear to contradict racist comments in his correspondence, and complicate the tale recent scholars tell about uniformly white or Anglo-Saxon model masculinities in the Gilded Age. See Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 46–47, 80–81; E. Anthony Rotundo, American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era (New York: Basic Books, 1993); Blake Allemendinger, “The White Open Spaces,” in Ten Most Wanted: The New Western Literature (New York: Routledge, 1998), 17–31; Dana D. Nelson, National Manhood: Capitalist Citizenship and the Imagined Fraternity of White Men (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998); Alan C. Braddock, “‘To Learn Their Ways That I Might Paint Some’: Cowboys, Indians, and Evolutionary Aesthetics” in Thomas Eakins and the Cultures of Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 153, 159, and 168; Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America: A Cultural History, 3rd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 67–70, 90–112. ↵

- John Ott, “How New York Stole the Luxury Art Market: Blockbuster Auctions and Bourgeois Identity in Gilded Age America,” Winterthur Portfolio 42, nos. 2/3 (summer/autumn 2008): 157–58. The late Jessie Poesch gave an important lecture on the “rocking horse” gallop convention in art many years ago that was evidently not published. ↵

- These photos first appeared in sequence format in “Les Allures du Cheval: représentées par la photographie instantanée,” La Nature 7, no. 289 (December 14, 1878): 23–26, repr. in http://cnum.cnam.fr/CGI/redir.cgi?4KY28.12. On the limits of visual perception and the limits of cognition, see Michael Leja, “Eakins and Icons,” Art Bulletin 83, no. 3 (September 2001): 483–87; and Michael Leja, “Eakin’s Reality Effects,” in Looking Askance: Skepticism and American Art from Eakins to Duchamp (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 59–92. ↵

- Remington used this head-on compositional device again the next year in Dismounted: The Fourth Troopers Moving the Led Horses, 1890, oil on canvas, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA. ↵

- This sculpture was and continues to be immensely popular; more than one hundred casts of Bronco Buster were made and sold during the artist’s life. See Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 66–67; also see Samuels, Frederic Remington, A Biography, 221–29. ↵

- Other versions of this “buddy rescue” genre include Aiding a Comrade, c. 1890, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, Hogg Brothers Collection; Wounded Bunkie, was Remington’s second sculpture, cast in 1896 and offered for $500. See “Remington and Russell: Timeline,” Amon Carter Museum of American Art, accessed July 30, 2014: http://www.cartermuseum.org/remington-and —russell/timeline?artist=All&narrative=1500. ↵

- According to the Amon Carter Museum curatorial files, this subject had appeared as a Remington drawing in The Century Magazine fourteen years earlier, and the artist had specifically designed the sculpture “to lift as many of the horses’ hooves off the ground as possible,” resulting in an exceptionally difficult casting and a $2,000 price tag in 1902 (The Wounded Bunkie was offered for $500 in 1896); the artist commented “So now I have six horses’ feet on the ground and 10 in the air.” See “Russell and Remington Timeline,” http://www.cartermuseum.org/remington-and-russell/timeline?artist=All&narrative=1500; also see Samuels, Frederic Remington, A Biography, 241. Other compositions on this theme include Cowboys Coming to Town for Christmas, 1889, oil on canvas, private collection; see Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 106. ↵

- See Blake Allmendinger, The Cowboy: Representations of Labor in an American Work Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992). ↵

- “Indians and Cossacks,” New York Times, December 25, 1890, 4. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- C. Hanford Henderson, “The Boy’s Summer,” in Porter Sargent, Handbook of Summer Camps (1924), 45; Alcott Farrar Elwell, “The American Private Summer Camp for Boys and Its Place in a Real Education” (Harvard Division of Education, 1916), 47, as cited in Leslie Paris, Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp (NY: New York University Press, 2008), 39, n. 74; Ernest Thompson Seton, “The Boy Scouts in America,” Outlook (July 1910): 633, as quoted in Phillip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 107; and Abigail A. Van Slyck, A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth, 1890–1960 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). See also Kimmel, The History of Men, 43–47, 97, 98. ↵

- Van Slyck, Summer Camps, 173, 180; and Lester George Moses, Wild West Shows and The Images of American Indians, 1883–1933 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996). ↵

- “Buffalo-Bill à Paris,” Le Figaro, May 12, 1889, 4; and Moses, Wild West Shows and The Images of American Indians, 1883–1933, 81–85. ↵

- Kimmel, Manhood in America, 62–77. ↵

- Tom Lutz, “Varieties of Medical Experience: Doctors and Patients, Psyche and Soma in America,” in Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra and Roy Porter, eds., Cultures of Neurasthenia from Beard to the First World War (New York: Rodopi, 2001), 53–57; and David G. Schuster, “Neurasthenia and a Modernizing America,” Journal of the American Medical Association 290, no. 17 (November 5, 2003): 2327–328. See also Tom Lutz, American Nervousness, 1903: An Anecdotal History (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), and E. Anthony Rotundo, “Work and Identity” in American Manhood, 185–93. ↵

- William Innes Homer, Thomas Eakins, His Life and Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1992), 196–205; and Braddock, Thomas Eakins and the Cultures of Modernity, 149–212. On Eakins and masculinity, see Martin A. Berger, “Painting Victorian Manhood,” in Helen Cooper, ed., Thomas Eakins The Rowing Pictures, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 102–23. ↵

- Thomas Eakins to Susan M. Eakins, Sept. 7, 1887, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Charles Bregler Collection, as quoted in Homer, Thomas Eakins, His Life and Art, 200. ↵

- Eakins’s laconic Cowboys in the Badlands found no buyer; see Braddock, Thomas Eakins and the Cultures of Modernity, 189; and Homer, Thomas Eakins, His Life and Art, 200. ↵

- Kimmel, Manhood in America, 105; also see White, The Eastern Establishment and the Western Experience. ↵

- “Paintings at the Academy,” 5. Note that The National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1861–1900, lists seven other Remingtons exhibited at the Academy between 1887 and 1899, but erroneously omits the notable exhibition of A Dash for the Timber in the fall of 1889; its presence is indicated in this New York Times article. See Maria Naylor, comp. and ed., National Academy of Design Exhibition Record 1861–1900 in Two Volumes (New York: Kennedy Galleries, 1973). See also “At the Academy of Design,” New York Herald, November 16, 1889, 4, where an unnamed critic noted that it was a “large and excellent work…the drawing is true and strong, the figures of men and of horses are in fine action, tearing along at full gallop, the sunshine effect is realist and the color is good.” Quoted in Shapiro and Hassrick, Frederic Remington: The Masterworks, overleaf plate 1, and Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 47. ↵

- Shapiro and Hassrick, Frederic Remington: The Masterworks, 20, 73. ↵

- The painting is identified as “A Dash for the Timber, loaned by E. C. Converse, Esq., New York” in an 1890 catalogue; the next item was Remington’s Cheyenne Scouts, also loaned by Converse. See Catalogue of Paintings Exhibited by the Following American Artists—J. Wells Champney, A.N.A., William M. Chase, A.N.A., Charles Melville Dewey, C. Harry Eaton, F. K. M. Rehn, F. D. Millet, N. A., Robert C. Minor, A.N.A., H. R. Poore, A.N.A., Frederick Remington, Carleton Wiggins—at the American Art Galleries on East 23rd Street, New York, beginning April 7 (1890), items 16 and 17. Other Remington works were loaned by Eastern elite men including eclectic collector Samuel B. Duryea, Esq. of Brooklyn, who collected illuminated manuscripts and bequeathed a live buffalo to the Prospect Park menagerie on his death in 1893. See Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 33; and Samuels, Frederic Remington, A Biography, 126–27; see also <http://genforum.genealogy.com/duryea/messages/158.html>. ↵

- “E. C. Converse Dies of Heart Disease,” New York Times, April 5, 1921, 19. Other Remington patrons include Horace G. Young and J. W. Burdick (both Albany, New York, transportation executives). See “Many Notable Works of Art: The Loan Exhibition for the Childs Hospital in the Albany Club,” New York Times, April 16, 1894, 12. ↵

- “E.C. Converse Dies of Heart Disease,” 19. The portrait of Count Rumford, unlike A Dash for the Timber, remained in his possession until his death as it was given to the Harvard Art Museums by bequest from Edmund C. Converse in 1922 (email communication to the author from Harvard University Art Museums staff member Tara Cerretani, July 8, 2011). ↵

- Catalogue of the Art Collection of the Saint Louis Exposition and Music Hall Association, Tenth Annual Exhibition, (St. Louis: 1893), no. 212. ↵

- H. W. Janson, with Dora Jane Janson, History of Art: A Survey of the Major Visual Arts from the Dawn of History to the Present (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1962). ↵

- H. W. Janson, “Centennial Address” (1981) in Sabine Eckmann, H. W. Janson and the Legacy of Modern Art at Washington University in St. Louis, exh. cat. (St. Louis: Washington University Gallery of Art, 2002), 45. ↵

- Ibid., 46. On Janson’s role in disparaging Regionalist painting and other American art, see Elizabeth Sears and Charlotte Schoell-Glass, “An Emigré Art Historian and America: H. W. Janson,” Art Bulletin 95, no. 2 (June 2013): 219–42, esp. 229–31. ↵

- Ibid. For a broader narrative of disparagement, see Brian Dippie, “Western Art Don’t Get No Respect: A Fifty-Year Perspective,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 51, no. 4 (Winter 2001): 68–71. ↵

- H. W. Janson, History of Art (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 482. ↵

- Writing to a friend in Arizona about sending him chaps (chapperras), Remington said “I want old ones—and they should all be different in shape.” See Gaye L.Brown,ed., West Comes East: Frontier Painting and Sculpture from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, exh. cat. (Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, 1979), 43; and Ballinger, Frederic Remington’s Southwest, 33. The celebration of Remington for documenting a passing way of life is a frequent refrain in journalism of his own era; see, for instance, ”Neglected Fields of American Art,” New York Times, December 22, 1901, 30; “Frederic Remington’s Soldiers,” New York Times, January 10, 1903, 31; and “Paintings by Remington: Grim Tragedies of the Plains Told in Strong Colors,” New York Times, March 15, 1904, 19. ↵

- The auction took place at Kende Galleries in New York City; 120 works were sold totaling $40,000 with which Janson bought forty works by European modernists. See Eckmann, H. W. Janson and the Legacy of Modern Art at Washington University in St. Louis, 23. ↵

- 100 of the World’s Most Beautiful Paintings (Smithtown, NY: Book Distributors, 1991), no. 80, n.p. ↵

- For an account of the longevity and popularity of Janson’s text and perspective, see Jeffrey Weidman, “Many are Culled But Few Are Chosen: Janson’s History of Art, Its Reception, Emulators, Legacy, and Current Demise,” Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 38, no. 2 (2007): 85–107. ↵

- Dippie, “Western Art,” 70. ↵

- Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988). ↵

- Alexander Nemerov, Frederic Remington and Turn-of-the-Century America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 5, 19; also see Stephen Tatum, In the Remington Moment (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001). ↵

- See for example, Leja, “Eakins and Icons,” 479. ↵

- Ibid., 490, 491. This developmental imperative continues to be evidenced, for instance, as in such insightful essays as Leja’s “Eakins and Icons,” which fits Eakins onto the canonical family tree of (European) modernism. Leja argues, “His paintings point the way toward modernist work on signs in Cubism, Futurism, collage, and Dada” and presents Eakins as “grandfather” to twenty-first century new media. ↵

- Remington does not appear, for instance, in such standard recent surveys of American art as Angela L. Miller, et al., American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2008). In other surveys, Remington receives terse mention and is described—echoing Janson—as inauthentic. See for example, Frances K. Pohl, Framing America: A Social History of American Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 237–38. Robert Hughes describes the artist as a “fat” person whose works are “facile” and “naïve”; see Hughes, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 203–5. Where Remington’s works are discussed they are usually invoked in invidious distinction in the course of discussions of Homer and Eakins, for instance, as in Randall C. Griffin, Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz, The Search for American Identity in the Gilded Age (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2004), 96–99, 126. ↵

- Letter from the office of the curator, White House, January 2, 1975, which includes a notation that the Remington statuette was placed in the Oval Office during the Gerald Ford administration, although the gift was made in 1973 during the vexed Nixon administration. See: http://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0204/1511864.pdf. The formal presentation occurred July 13, 1976: http://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0036/pdd760713.pdf. ↵

- In 1898, the First Volunteer Infantry (Rough Riders) mustered out and presented Bronco Buster to Col. Theodore Roosevelt. See http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/the-american-west-in-bronze/blog/posts/roosevelt. ↵

- The Bronco Buster in the White House collection was acquired in 1973; it was a gift of Miss Virginia Hatfield and Mrs. Louise Hatfield Stickney in memory of James T. Hatfield. See Doreen Bolger and David Park Curry, “Art for the President’s House: A Historical Perspective,” in William Kloss, et al., Art in the White House: A Nation’s Pride (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 197. This pair of Kentucky sisters donated it “believing its display in the White House would ‘inspire a feeling of strength and determination of the American spirit’”; see “President Greets Hatfield Sisters,” The Kentucky Post, July 14, 1976, as quoted in Kloss, Art in the White House, 21, 23. The White House collection of American art consists of about 450 objects, initially consisting of portraits, after 1961 it included a broader spectrum of paintings and decorative arts objects. For photographs of presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama in the Oval Office that conspicuously include Bronco Buster, see http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_tmWedyO-hjw/S20Nv8vDuUI/AAAAAAAAANo/jvCukc3EPn8/s1600-h/bush-feet-on-desk.jpg; and http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/af/Barack_Obama_thinking,_first_day_in_the_Oval_Office.jpg; http://www.whitehouseresearch.org/ accessed May 30, 2011. ↵

- Richard Slotkin, The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1880–1890 (New York: Atheneum, 1985), 16–19, 531. ↵

- Griffin, Homer, Eakins, and Anschutz, 97–98. ↵

- Other Remington works that thematize unspoken signs and pantomime language include: Signaling the Main Command,1886, engraving of an oil painting, Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY; The Blanket Signal, c. 1896, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, Hogg Brothers Collection; The Buffalo Signal, Bronze, 1902, National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center, Oklahoma City, OK; and Pony Tracks in the Buffalo Trails, 1904, oil on canvas, Amon Carter Museum of American Art. ↵

- Clifford Geertz, “Deep Play: Notes on The Balinese Cockfight,” Daedalus 101, no. 1 (1972): 1–37. ↵

- Nancy K. Anderson, ed., Frederic Remington: The Color of Night (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art and Princeton University Press, 2003), esp. “Dark Disquiet: Remington’s Late Nocturnes,” 52–75; see also Tatum, In the Remington Moment. ↵

- “Paintings at the Academy,” 5; art critic William A. Coffin opined “that Eastern people have formed their conceptions of what the Far-Western life is like, more from what they have seen in Mr. Remington’s pictures than from any other source.” See ”American Illustration Today,” Scribner’s Magazine 11, no. 3 (March 1892), as quoted in Burns and Davis, American Art to 1900, 636. ↵

- Anne F. Hyde, “Cultural Filters: The Significance of Perception in the History of the American West,” The Western Historical Quarterly 24, no. 3 (August 1993): 351–53, 359–61, 366–669. ↵

About the Author(s): Margaretta M. Lovell is the Jay D. McEvoy Jr. Professor of American Art at the University of California, Berkeley.