Ecstatic Time

PDF: Witt, Ecstatic Time

Over the course of the past decade, the New York–based photographer Irina Rozovsky visited Brooklyn’s Prospect Park with a repetitive and compulsive task: to photograph the park and its visitors at all times of the day and year. The idea for the project first came to the artist by chance in 2011, when she noticed solitary individuals and groups of people assembled in secluded sections of the park. To Rozovsky, Prospect Park seemed to distill all of New York into a constellation of scenes and figures—teenage couples, South Asian fisherwomen, Hasidic families, hip hop dancers, practitioners of Tai Chi, a black cat. Each scene was like its own world. Worlds upon worlds upon worlds. Rozovsky pictured these worlds as she encountered them: she photographed people communing with nature, drinking with friends, sleeping under the shade of a branch, lying in fresh snow, practicing the violin, or losing themselves in a conversation or embrace (fig. 1). A whole decade of the artist’s work is now condensed in a book of photographs titled In Plain Air (2021), published by MACK Books.1

While working on her project, Rozovsky began to grasp the park as a living organism—a site that seemed to possess its own life, vitality, and power. After each visit, she would reflect on how the park held the capacity to channel moments of levity and elation but also absorb the sadness and melancholia of its visitors. Whether these feelings were pictured as instances of serene calm or intoxicated joy, cold indifference or busy activity, Rozovsky sought to take account of their depth and measure.

To her, the experience of photographing the park and its visitors, week after week, month after month, felt bottomless and all-encompassing. Her visits to the park were so regular that they began to take on a ritualized feeling. On some days, it appeared as though the park could swallow her whole; at other moments, coldly repel her. In a recent talk for Aperture magazine, Rozovsky described the feeling conveyed in her images as a “lazy moment,” but looking closely at her photographs, what we find is perhaps something different, something more ecstatic and effervescent, a moment when the everyday appears before her camera transfigured and re-enchanted (fig. 2).2

When flipping through Rozovsky’s photobook, the viewer gets an overriding sense of disorientation. Just as there are no captions distinguishing one photograph from the next, there are no definitive markers that locate us in familiar sections of the park, no logical flow between seasons. The pages evoke a sense of loss and confusion, both spatial and temporal. The meandering opening sequence makes this sense of disorientation apparent: it begins with an indistinct photograph of the lake in summer, followed by a photograph of a woman laying down in fresh snow, and then a photograph of a man raking the edge of the lakeshore. Before we are shown the title page of the book, Rozovsky completes this short sequence with a photographic close-up of rock found in the park crowned by a snaking garland of flowers. This last photograph is like a punch to the gut, a blockage to meaning and experience.

Published in spring 2021, at the height of the global COVID-19 pandemic, In Plain Air quickly sold out after its first printing. When viewed through the lens of lockdown and social distancing, Rozovsky’s images are immediately appealing. Perhaps what made her photographs so poignant, so alluring, is that her vision amplified how precarious the conditions of being together and being in common were—a vision whose power and strength became glaring in the context of so much isolation, loneliness, banality, tragedy, and death. “Usually we feel grateful to have a home but in recent months I feel grateful to have the outside,” Rozovsky stated to AnOther Magazine in the context of the pandemic and In Plain Air.3

Drifting through Prospect Park with camera in hand became an opportunity to wither time away4—to stare into another’s face, to lose herself in a landscape or scene, or simply to surrender to the beauty of the world. These are moments that appear at once ecstatic (outside of time, outside of oneself) and also tightly circuited to the accelerated pace of contemporary life: its sorrow, anguish, and indifference. Drawing our attention to these images of a life outside, Rozovsky’s work asks us to reconsider a set of pressing questions about the transfigurative powers of contemporary photography: What does it mean to make a world? Do her images show us more than the enchantment of the familiar, or are they merely specters of a time now lost?

§

A year before Rozovsky started photographing Prospect Park in earnest, the British photographer and educator Paul Graham gave a presentation during the first Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Photography Forum (February 2010) that expressed dismay with the lack of attention paid by museums, galleries, and the art press to a mode of photographic work—like Rozovsky’s images—that dealt with the social world. Graham’s presentation took issue with a review he had encountered in a contemporary art magazine (which he did not name) that celebrated the work of Jeff Wall for constructing his pictures as “compelling open-ended vignettes, instead of just snapping his surroundings.”5

Graham was annoyed with this last phrase. What he took issue with was not Wall’s work, exactly, but rather how the review relegated the whole practice of photography to a mindless, mechanical operation (“just snapping his surroundings”). This throwaway phrase, Graham claimed, did a disservice to most photographic work that was situated in the social world. Regardless of whether this world was encountered on the street, in a park, or within an interior, what photographers did in these spaces seemed to evade analysis.

Graham inferred, however, that if one was to survey the work of photographers who were based in the social world—from Walker Evans to Diane Arbus to Irina Rozovsky—most viewers and critics would accept that there was a formal complexity to the work that demanded a reading on its own terms. For Graham, what made the work of Wall so appealing was that his audience could easily grasp and understand the artist’s creative process—it was plain to see what Wall had done to the images, and his process could be clearly articulated. In contrast, for photographers who work in the social world—a world that is not manipulated or fabricated—this process is harder to grasp or talk about.6 Again, Graham was not opposed to Wall’s work itself, which he admired, as he stated clearly in his talk. Instead, his contention was with what he saw as the paucity and inadequacy of contemporary art criticism and the art press, which lacked the vocabulary or desire to come to terms with what most photographers do.

When we look at the work of Rozovsky, we realize that the photographer has done something to the image, but what this something is has escaped our awareness (fig. 3). In his own formulation, Graham saw this type of work as a form of world-making—work that transforms the randomness and meaninglessness of the world into a series of photographs and then arranges those photographs into a meaningful world.

Graham titled his essay “The Unreasonable Apple.” His title is taken from a popular parable of an isolated community that grew up only eating potatoes and, when presented with an apple, thought it unreasonable and useless because it did not taste like a potato.7 This unreasonableness, Graham writes, is analogous to the awkward position of still photography in the museum system, a discursive system that is unable to account for the uncertain status of unmanipulated imagery—imagery that confronts the world as it is.

While not arguing for a simplistic opposition (still photography versus the art world), Graham’s talk reads as an impassioned plea for a new criticism that surfs above the wave of most art writing to address other pockets of creative life. Photographers of this type, Graham writes (not naming them explicitly), grapple with the medium’s capacity to picture specific moments in time, so that when they reach us in the present, we are able to grasp, there and then, what the photographers had once perceived. Graham speculates that it is through this weaving of the past and present—the past of creation and the present of the work’s reception—that we might glimpse the contours of creative still photography, claiming it is “nothing less than the measuring and folding of the cloth of time.”8

Perhaps what makes the photographic image so bewildering, so strange, is this complex weaving of the past and the present. For Fredric Jameson, this is what distinguishes the photograph as “an anomaly in the world of objects,” which he defines as the simultaneous existence of the photographic image as suspended between the past and the present: the past of the photograph’s production (what Roland Barthes famously calls the “that-has-been”) and the eternal present of the photograph’s reception.9 According to Jameson, this ontological paradox is at the core of most critical accounts of the medium. From Benjamin to Barthes, Sontag to Graham, each writer has insisted that this peculiar property of photography is something that cannot be explained outright, only described.

§

Unlike most images shot in the social world, Rozovsky’s photographs for In Plain Air were not composed as snapshots. Her photographs of Prospect Park mark intervals of time, not instants. Similar to painting en plein air, the explicit source of the title In Plain Air, Rozovsky’s photographs spurn the aesthetic of the snapshot and assume a slower, studied, and more methodical form and composition. There is a sense in some of Rozovsky’s images that her figures are assembling themselves on a stage for some inexplicable performance, as though they are positioning themselves before her camera just seconds before the curtain will be raised, their bodies held in abeyance, as though suspended in some interminable present. We catch sight of this suspended moment in a photograph of a man cleaning the shore of the lake in a secluded section of the park (fig. 4). From his gait and stature, it appears as though he is readying the park for a personal ceremony, as if this small slice of park is his own living room.

In a similar fashion, the man and woman who are pictured on the shore of the lake holding their hands out to the sun appear frozen almost like statuary, as though someone outside of the picture grabbed a remote, pressed pause, and stilled their movement. Amid this theatrical play, Rozovsky’s camera also pictures her sitters breaking through this performative haze, confronting us directly in their immediacy, without artifice. They look out toward the photographer as if they have no concern in the world, no consideration of thought, no notice of the passing of time. Her figures stand before her camera as if they were standing outside of time.

Similar to the Civil War photographs of Alexander Gardner that Rozovosky admires, her photographs reach toward stillness. Consider the photograph of a reclining figure resting against a stump of a tree (fig. 5). Rozovky’s figure strikes a similar pose to the iconic picture of Lewis Payne, one of the Lincoln conspirators, which Barthes prized in Camera Lucida as an example of the punctum.10 For Barthes, what we see in Gardner’s image is a death foretold: “The punctum is: he is going to die.” Barthes writes, “I read at the same time: This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. By giving me the absolute past of the pose (aorist), the photograph tells me death in the future.”11

Death does not haunt Rozovosky’s images, however, as they do Gardner’s. In the warm light of the evening air, her figures assert their presence before her camera—calmly, joyously, radiantly—as if their stance and posture were an immediate response to the world: its cruelty, anguish, and indifference.

§

Part of the power of Rozovsky’s images is their understanding of everyday life as a sanctified space, a space where presences are felt, here and now, directly and immediately. Her figures know that this moment is eternal and enduring despite its transient nature. Rozovsky’s pictures are akin to what the sociologist Émile Durkheim calls a form of “collective effervescence,” the joy and elation experienced in states of temporal synchronicity.12 Taking a closer look at the images from In Plain Air, we catch sight of this elation in the glow emanating over the lake, the smile on a young boy’s face, the ground upon which Rozovsky’s couples lie in an embrace (fig. 6).

Perhaps what Rozovsky’s camera attempts to reveal in these images is how the everyday is always already marked by elation and effervescence—or, at the very least, by their potential. Although the moment may never arrive, and its presence remains a mystery, every image contains this potential as a suspended moment. Rozovsky pries open this moment as if it were a door.

Surveying Rozovsky’s photographs for In Plain Air, this suspended moment insinuates itself, paradoxically, in her images shot at sunrise and sunset. Attuned to these transitional scenes and states, Rozovsky’s camera seeks to reveal what emerges in those in-between moments of first and last light. Her photographs not only chronicle the park’s transformation—where the day drifts into night or night slips into day—but also intuits this moment as a transfigured state.

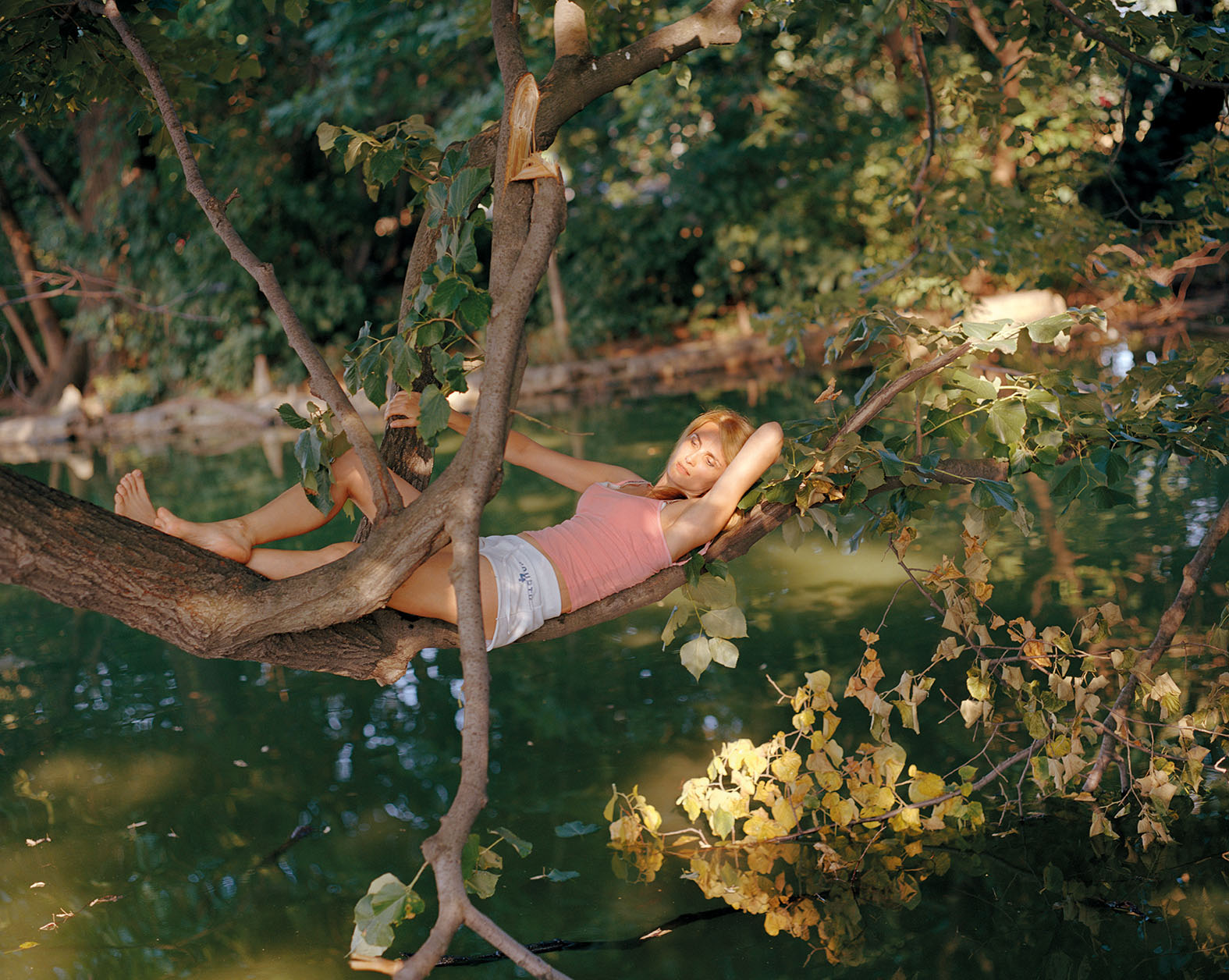

Consider the lounging figure appearing halfway through the photobook. With her eyes lost in thought, Rozovsky’s figure does not shut herself off from the world, but she appears to lose herself to it, and while lost, she seeks a way to be taken outside of herself, gliding somewhere else beyond herself (fig. 7). This figure evokes a decidedly different time: a time free from labor, a time of rest, and a time of dreams.

In the history of photography, recumbent and sleeping figures are often overcoded as ciphers of extreme poverty or destitution, pictured as unresponsive and docile sitters who lie still for the photographer. Yet, what is often neglected in this conversation is the obscure content represented by the sleeping figure’s dream, which conjures a world away from exhaustion, beyond the unceasing tempo of capitalist productivity, order, or control. Rozovsky’s moment is a moment of reverie, a moment when the image no longer represents the limits of the world but points to an experience beyond it, an experience that seeks to alter the everyday flow of time.

§

A decade after Graham presented his paper “The Unreasonable Apple,” the photographer was invited to curate an exhibition at the International Center for Photography in New York City that pushed the argument of his essay to its logical conclusion. Graham’s exhibition, But Still, It Turns (February 4, 2021–August 15, 2021), presented the work of eight photographers he admired who worked in a direct photographic mode—a mode that took the “world-as-it-is,” as he called it. Graham planned the exhibition before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the dates of the exhibition and the release of his essay for the show landed in the middle of the pandemic.

The exhibition’s title, But Still, It Turns, derived from what the astronomer Galileo Galilei apparently uttered under his breath as he exited his inquisition, after being forced to renounce his observations that the earth rotated around the sun (and not the other way around). Although Graham does not explicitly name his current political moment, he writes how the critical power of the title seems pertinent to our shared moment, characterized by the prevalence of anti-truth politics, political polarization, rising right-wing populism, and authoritarianism.13 In a time of pandemic and quarantine, however, Graham was struck by how the critical valence of the title had also changed, serving as a positive reminder and hopeful promise that life will go on.

To historicize his argument, Graham notes that the conditions of photographic production and circulation have shifted dramatically since the rise of the medium in the twentieth century. Unlike the previous century, when photography found its home in illustrated magazines and periodicals, during this past decade, many magazines and periodicals have shut down or limited their circulation, and the internet has grabbed images for free. Lost in this altered environment, Graham claims, is an important platform and a vital source of income for photographers, as well as the constraints of an editorial framework, the subsumption of an image to a narrative arc or illustrative function. Graham defines our time as post-documentary and reads this loss of illustrative function, editorial prompt, and narrative arc as a form of emancipation.

On the surface, Graham’s characterization of the moment as post-documentary might seem correct, but the situation appears more complicated when we consider the fact that some of the photographers featured in Graham’s exhibition have self-identified as working within the documentary genre, often in wildly different modes. From Gregory Halpern’s mythopoetic travelogue of the California desert in ZZYZX (2008–16) to RaMell Ross’s documentation of the American South in the series South County, AL (a Hale County) (2012–20), both artists have identified with the documentary genre as a means to renew a tradition but also to suture their work to a revived fight over photographic truth—what Ross calls “a truthful way of looking” (fig. 8). For Ross, a truthful way of looking is found in the contingency and indeterminacy of the world. “You use the documentary genre because it’s a space where people are predisposed to truth, which is a great, great entryway into an idea,” Ross remarks on his critically acclaimed, Academy Award–nominated film Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018). He states, “The premise of truth puts viewers in the frame of mind to receive larger truths.”14

What are these larger truths? Truth is a complicated business; it does not always hinge on right or wrong, fiction or nonfiction. Photographic truth, moreover, is just as hard to pin down. Perhaps any glimpse of truth is only uncovered in the provisional nature of the moment, as figured in Ross’s photographs of a child using metal fencing as a hammock, three teenagers sitting on a swing set lost in the moment, or a man and two children playing basketball on a grassy field (fig. 9). Together, the sum of experience contributes to what Ross calls, in his 2019 manifesto “Renew the Encounter,” published in Film Quarterly, the “epic banal.”15

Similar to the situation of Rozovsky’s photographs of Prospect Park, if there is a truth to these images, it is a truth approached obliquely, pictured through indecisive moments, personal and poetic encounters, experiences that appear, from a distance, elated and effervescent but also, ultimately, unknowable: “Personal time to personal truth,” to cite Ross again.16 This is one way to grasp Ross’s “epic banal,” a mode of perception that provides a means to picture the everyday condition of Blackness in America in an alternative light.17 Perhaps the clearest example of this condition is Ross’s photograph of a child bending a chain-link fence to stare at the sky. To be outside, to purposefully bend down a chain-link fence in order to gaze up in the air, produces its own truth. A truthful way of looking is precisely this: an experience where we are taken outside of ourselves, outside of the everyday flow of time. An ecstatic truth, an ecstatic time.

§

Whether the present moment can be classified as post-documentary or not, the liberation from the strictures of an editorial prompt or script have allowed photographers like Ross and Rozovsky to work with what can be described as the messy tangle of dispersed places and lives, in what Graham names “earthly facts and chance collisions, history and its shadow, to form or echo some kind of interconnectedness.”18

To return to a line from “The Unreasonable Apple,” the photographer who aims her camera to the world-as-it-is attempts to transform the world’s apparent meaninglessness and randomness into a series of photographs, which can then be formed into a meaningful world. As a mode of world-making—as a means to share the world—the medium illuminates the indeterminate and fragile connections that link us to one another, as well as our experience of time and the present moment (fig. 10). This emphasis on indeterminacy is befitting still photography’s fundamental aesthetic quality: the experience of contingency, a quality that we can interpret as perhaps obscured and forgotten in the current historical moment.

For Graham, any advanced photographic work that treats the world-as-it-is has no choice but to do away with the narrative demands of photographic illustration and closed sequencing and instead to strive to live with indeterminacy, to linger in the provisional and contingent encounters of the world, and to transform these encounters into a constellation of meaning and memory:

Through photographs, the prism of time is illuminated and breaks to clarity. We see the components and how they fit together. They take us on unexpected paths, they bring us to other lives we could know if life turned another way; they foster empathy for our fellow citizens, for lives not our own. They allow us to recognize that life is not a story that flows to a neat finale, it warps and branches, spirals and twists, appearing and disappearing from our awareness.19

§

What do we make of this experience of time that Graham describes, an experience that warps and branches, spirals and twists, appears and disappears from our awareness? Perhaps one way to understand it is to read both Ross’s and Rozovsky’s images as the filmmaker and writer Hollis Frampton might. Both photographers’ images of rest and reverie articulate a distinction between what Frampton in an 1974 essay calls “historic time” and “ecstatic time.” For Frampton, historic time is the time of clocks and regimented routine. In contrast, ecstatic time is not captured by the time of regiment and control; it is a time experienced during sleep and reverie, intense emotions, and erotic rapture. “Historic time is the time of mechanistic ritual, of routine, automatic as metabolism,” Frampton writes. It is the time of “implied causality,” a time composed of “sequential, artificial, isometric modules which are related to one another in language, by the connective phrase: ‘and then.’”20

Under ecstatic conditions—sleep, reverie, dream, erotic or aesthetic activity—the mind experiences the world differently (fig. 11.). “For an ecstatic moment, time is not,” Frampton writes. His examples involve extreme conditions: terror, rage, erotic rapture, suicidal despair, sleep, or the influence of certain drugs. In each of these states, consciousness appears to have entered into a distinct domain.21 It is a time when distinct units of measurement—seconds, minutes, and hours—appear to have been altered, extended, or stopped entirely.

In a 2004 interview published in the Paris Review, the poet Anne Carson describes this temporal condition in similar terms. The experience of the ecstatic is “the principle of being up against something so other that it bounces you out of yourself to a place where, nonetheless, you are still in yourself; there’s a connection to yourself as another.”22 For Carson, the experience of the ecstatic is envisioned as a radical discontinuity found in the depths of the subject’s own being; it is a moment through which a different mode of experience, perhaps even a different world, is viscerally present. Under ecstatic conditions, you experience something that is not you. And yet, what makes the experience of the ecstatic dialectically related to historic time is that the ecstatic is its own form of historical consciousness—a consciousness that falls under the spell of temporal enchantment, a time that is complex and convoluted, inexplicable and irreducible, elated and effervescent.

Coming back to Rozovsky’s photographs, we can think of this experience as a form of perception that is just past the threshold of understanding but is also, in its own way, its own truth: a mode of semi-consciousness that is located outside of the confines of historic time yet remains grounded in history through its disruption and subversion of the logic of the world.

§

When viewed through the lens of lockdown and social distancing, Rozovsky’s vision of Prospect Park is immediately appealing. Her work not only provides a glimpse into the recent past, but her project also instills an anticipatory promise—a promise of something to come—a moment in the middle of an ongoing pandemic where New Yorkers will (and have) rediscovered the joys of being-together, being-in-common, being-in-nature, and experiencing beauty in the aftermath of so much suffering.

To read Rozovsky’s photographs in the absence of this context threatens to flatten and distort their message into what Joan Didion calls, in a 1991 essay on New York, a “sentimentalization of experience,” a fundamental trope of New York City narratives, which tends to reduce the messy specificity of a life into an easily recognizable narrative:

Lady Liberty, huddled masses, ticker-tape parades, heroes, gutters, bright lights, broken hearts, eight million stories in the naked city; eight million stories and all the same story, each devised to obscure not only the city’s actual tensions of race and class but also, more significantly, the civic and commercial arrangements that rendered those tensions irreconcilable.23

In the context of 2020 New York, the life-giving quality of Prospect Park is dialectically related to how much life was put in question over the last two years, not only with respect to the pandemic but also in relation to the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the documented lynching of Ahmaud Arbery in the streets of Glynn County, Georgia.24

As Hannah Black writes in her Year in Review column for Artforum, appropriately titled “Go Outside,” the rediscovery of the “outside” is directly related to the calls for justice against police violence, restrictive curfews, and social and economic inequities exacerbated by the pandemic. “When the young people say, New York will breathe, or, Abolition now, they mean it,” Black writes, “They go outside, and, for a few hours, they make an image of the present condition of freedom.”25

For Black, Prospect Park serves as a meeting ground for young lovers, rioters, and prison and police abolitionists to cultivate a community of social and political solidarity:

After the riots, before the winter, the city was like a creature in between exoskeletons. It turned out everything could happen outside. In summer, the parks were dense with people and competing musics. Grill smoke and weed smoke and Pop Smoke outlined the spectral presence of the New York commune that lived a second ghost life after its erasure by politics. I walked dark streets with people I had met on apps and navigated suddenly ornate boundaries of touch. On Jacob Riis Beach, we swam at night and interrupted someone else’s sex. Groups of young abolitionists still high on outdoor life congregated fleetingly in different parts of the city to eat and talk. It was romantic to see how everyone had grown into one another. In Prospect Park, we lay in the bowl of the earth and watched the sky tear itself into sunset. “I’ve been out every day,” a friend told me in October, “since the first day of the riots.” With winter coming, we rediscovered fire, as if rewinding back to the first language-animals who lived when history had yet to happen. I remember in the image of riot the hyperadaptability of being.26

By the strength of the experiences that Black describes, these sensations—these cracks, fissures, and holes in time—Prospect Park is pervaded and infused with another time, a vaster and stranger temporality that might not be immediately visible or graspable all at once.

When the streets and parks of New York were flooded with protests over police brutality, Rozovsky was no longer living in New York, having moved to Athens, Georgia, two years before. An artist who was there to picture these events was the painter Nicole Eisenman, who figured this collective demand for justice, retrospectively, in the painting The Abolitionists in the Park (2020–21; fig. 12). It is striking how Eisenman’s painting resembles Rozovsky’s photographs. Eisenman’s figures are shown in everyday states—sleeping, smoking, lounging, and eating together—but the painting also alludes to an experience beyond the everyday. Similar to Rozovsky’s images of collective reverie (fig. 13), Eisenman’s painting is attuned to the nourishing effervescence of the moment, of being-together. This effervescence is dramatized not only by the glow of the moon at the top-right corner of the picture but also by the many characters who populate its surface as an extension of this glow, emissaries of the moon’s transfigurative radiance.

The two central figures of Eisenman’s painting are, in fact, two of Eisenman’s friends, Hannah Black and Tobi Haslett. And yet, to read Eisenman’s painting as a work of photographic reportage misses the point. Eisenman’s painting is not a record of the past, like a photograph. But similar to the temporal signature of Rozovsky’s images, Eisenman’s painting is anticipatory, prophetic, to cite the work of John Berger on the time of painting.27 The look with which Black greets the viewer is a look not only addressed to the present but also to the future. Its message is the demand for police and prison abolition, the promise of emancipation. Obstinate and searching, Black’s assured presence speaks without speaking the following words: We are here. We will not move. We demand abolition. We demand justice.

What is lost and what is redeemed in Eisenman’s painting, in Black’s account, or even in Rozovsky’s photographs is ultimately up for grabs, but perhaps this desire to “go outside” is a way to be outside of time, possibly even to be outside of history, and ultimately to experience life as if you were free, as though the world could be made otherwise.

Cite this article: Andrew Witt, “Ecstatic Time,” in “About Time: Temporality in American Art and Visual Culture,” In the Round, ed. Hélène Valance and Tatsiana Zhurauliova, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15126.

Notes

Versions of this paper have been presented at a number of institutions, and I would like to thank the organizers and audiences at each for their comments and feedback. For their insightful advice and encouragement, I would like to thank especially Nathan Crompton, Nicole Eisenman, Annika Fisher, Katherine Jentleson, Amy Kazymerchyk, RaMell Ross, Jessica Skwire Routhier, Irina Rozovsky, Hélène Valance, Keri Watson, and Tatsiana Zhurauliova.

- Irina Rozovsky, In Plain Air (London: MACK, 2021). ↵

- “Aperture Conversations: Artist Talk with Irina Rozovsky,” Aperture, April 9, 2021, video, 53:01, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qoL47ANlxuI. ↵

- Dominique Sisley, “A Dreamy Day Out: A Cinematic Portrait of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park,” AnOther Magazine, March 10, 2021, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/13148/brooklyn-prospect-park-in-plain-air-irina-rozovsky-photographer-mack-book. ↵

- My use of this distinct idiom is inspired by Jill Mulleady’s public installation We Wither Time into a Coil of Fright (2020). See “Jill Mulleady,We Wither Time into a Coil of Fright,” Whitney Museum of American Art, accessed October 20, 2022, https://whitney.org/exhibitions/jill-mulleady. ↵

- See Paul Graham, “The Unreasonable Apple,” presentation at the first MoMA Photography Forum, February 2010, Paul Graham Archive, http://www.paulgrahamarchive.com/writings_by.html. ↵

- This argument could be extended to other photographic work as well, such as the self-portraits of Cindy Sherman or the sculptural creations of Thomas Demand. “In each case,” Graham insists, “the handiwork of the artist is readily apparent: something was synthesized, staged, constructed or performed” (“The Unreasonable Apple”). ↵

- Graham, “The Unreasonable Apple.” ↵

- Graham, “The Unreasonable Apple.” ↵

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang 1980), 76; Fredric Jameson, The Benjamin Files, (London: Verso, 2020), 179. ↵

- Alexander Gardner, photograph of Lewis Thornton Powell, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, NPG.80.172, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.80.172. ↵

- Barthes, Camera Lucida, 96. ↵

- Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. Karen E. Fields (New York: Free Press 1995). ↵

- Sasha Wolf, host, “Paul Graham – Episode 25,” PhotoWork with Sasha Wolf (podcast) June 17, 2021, accessed October 17, 2021, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/paul-graham-episode-25/id1523742299?i=1000525888357. ↵

- RaMell Ross, quoted in Rebecca Bengal, “And the Clock Waits So Patiently,” in But Still, It Turns: Recent Photography from the World (London: MACK, 2021), 94. ↵

- RaMell Ross, “Renew the Encounter,” Film Quarterly 73, no. 3 (March 1, 2019): 19. ↵

- RaMell Ross, “Some Other Lives of Time,” Museum of the Moving Image, March 10, 2022, 27, https://www.ramellross.com/Some-Other-Lives-of-Time. ↵

- Ross, “Some Other Lives of Time,” 27. ↵

- Paul Graham, “Belonging Particles,” in But Still, It Turns, 15. ↵

- Graham, “Belonging Particles,” 15. ↵

- Hollis Frampton, “Incisions on History / Segments of Eternity,” On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), 40. ↵

- To put it more succinctly, in the words of Theodor Adorno, “Aesthetic time is to a degree indifferent to empirical time, which it neutralizes”; Aesthetic Theory, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 107. ↵

- Anne Carson, “Anne Carson, The Art of Poetry No. 88,” interview by Will Aitken, Paris Review, no. 171 (Fall 2004), https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/5420/the-art-of-poetry-no-88-anne-carson. ↵

- Joan Didion, “New York: Sentimental Journeys,” New York Review of Books, January 17, 1991, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1991/01/17/new-york-sentimental-journeys. ↵

- See also “Ahmaud Arbery was murdered or, more accurately, lynched,” USA Today, November 24, 2021, updated December 8, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/todaysdebate/2021/11/24/ahmaud-arbery-modern-day-lynching/8723517002. ↵

- Hannah Black, “Go Outside: Hannah Black’s Year in Review,” Artforum 59, no. 3 (December 2020), https://www.artforum.com/print/202009/hannah-black-s-year-in-review-84376. ↵

- Black, “Go Outside.” ↵

- “Paintings are prophecies received from the past, prophecies about what the spectator is seeing in front of the painting at that moment. Some prophecies are quickly exhausted—the painting loses its address; others continue.” Emphasis added. John Berger, “Painting and Time,” in The Sense of Sight: Writings by John Berger, ed. Lloyd Spencer (New York: Vintage, 1985), 206–7. ↵

About the Author(s): Andrew Witt is an Affiliate Fellow at The ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry.