Edward Hopper and the American Hotel

Curated by: Leo G. Mazow, Louise B. and J. Harwood Cochrane Curator of American Art at Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, with assistance from Sarah G. Powers

Exhibition Schedule: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, October 26, 2019–February 23, 2020; Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, June 6–September 13, 2020

Exhibition Catalogue: Leo G. Mazow with Sarah G. Powers, Edward Hopper and the American Hotel, exh. cat. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in association with Yale University Press, 2019. 216 pp.; 267 color illus., including two removable maps. Softcover: $40.00 (ISBN: 9780300246889)

Edward Hopper and the American Hotel is a monographic show that promises, in its titular scope, to be broader than its singular champion. The exhibition, organized by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in partnership with the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, explores the ties between Hopper’s work and the industry and built environment of hospitality. As the exhibition makes plain, Hopper, who was a frequent traveler, was deeply familiar with hotels, tourist homes, motels, and other hospitality services, such as luggage assistance and restaurants. Hotels and their dualistic trappings of mobility and rest, and of isolation and community, figure prominently in his work. Hopper’s paintings and works on paper generally depict either specific places he saw or imaginary syntheses of such scenes. By leveraging both this hyper-specificity of place and predictable sameness, Hopper’s oeuvre can be likened to the experience of hotels themselves. This is the unique strength of using Hopper’s work to examine the history of the American hospitality industry during the early to mid-twentieth century. Of course, Hopper was not the only artist to explore this longstanding tradition within American culture. The exhibition includes works by other artists, such as Richard Caton Woodville, John Sloan, and George Segal, to describe a broader history of the hotel and its visual manifestations.

After passing under a highway-scale sign for the show (fig. 1), visitors are greeted at the entrance with a paper “travel guide” that routes them through the exhibition’s thirteen thematic vignettes. The thin, vertical format of the paper guide recalls the American Automobile Association’s TripTik Travel Planners, serving as a playful reminder of travel in an era before the immediacy of Google Maps. The exhibition’s journey charts Hopper’s engagement with hospitality sites across his five-decade-long career, spanning commercial illustrations for hotel trade publications from 1920 to 1925, large-scale oil paintings of isolated figures—predominantly women—in hotel and motel settings from the 1920s to the 1950s, and landscapes on canvas and paper that document his own trips to coastal New England in the 1910s to the 1930s and to Mexico in the 1940s. Travel, and specifically hotels, increasingly defined a shared cultural experience for Americans during this period, due to an expanded middle class able to participate in tourism, an increase in automobile ownership, and networks of railroads and highways.

Using Hopper’s own movements as an organizing device, the exhibition’s themes coalesce in a loosely chronological way around diverse settings and modes of encounter—both inside and outside the hotel itself. For instance, the “travel guide” directs the viewer through cheekily titled sections, including: “Checking In,” featuring Hopper’s Hotel Lobby (1943; Indianapolis Museum of Art); “Getting Settled,” anchored by Hotel Room (1931; Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional); “Enter the Motel,” focusing chiefly on Western Motel (1957; Yale University Art Gallery) and the rise of motels; “A Change of Scenery,” centered on Hopper’s life on Cape Cod with his wife, Josephine (Jo) Nivison; “Postcards from the Road,” highlighting their 1940s–1950s road trips through the United States and Mexico; “Inside Looking Out,” probing Hopper’s use of the window as a pictorial device; and “Checking Out,” addressing the passage of time and the demise of railroad travel. These are just a handful of the show’s groupings. Woven into this narrative, via text panels and objects of material culture such as postcards, are insights into the history of hotel design and labor, the history of tenancy and urban lifestyles, and reflections on sociality and comfort.

The exhibition combines rich archival materials with novel approaches to installation. For example, the gallery with Hotel Lobby displays Hopper’s preliminary sketches alongside the painting to explore the artist’s working methods. By comparing the sketches to the final painting, visitors can track how Hopper modified figures and compositions and speculate on the effects of these modifications. The wall text beside Hotel Lobby reproduces a 1924 diagram from the trade journal Hotel Management that illustrates “methods of placing furniture on rugs,” pointing to the importance of interior decoration in this period. The perspicacious visitor’s attention might then be drawn to the design of this particular gallery, in which a strip of grass-green carpet, three gray upholstered chairs, and a classicizing dark wooden archway mime the interior design of the very lobby in Hopper’s painting (fig. 2).

These curatorial strategies call attention to the physical space of the gallery, forming a connection between the world of Hopper’s paintings and that of the built environment. The paradigmatic instantiation of this connection is the exhibition’s much buzzed-about gallery-turned-guest room: a physical re-creation of the motel room depicted in Western Motel, available for overnight bookings at $150–500. The painting’s setting recalls several places where the Hoppers stayed in El Paso, Texas, in 1952, including the Weseman Motor Court and the Western Motel. On display are period images from these motels, a reproduction of an advertisement for the Simmons Company furniture that would have decorated these rooms, and a charcoal study for an earlier version of the painting—all helping visitors mentally reassemble the Hoppers’ lived experience of the Western midcentury motel. The installation might have the effect of forcing visitors to consider physically inhabiting a Hopper motel painting, and, whether intentionally or not, raising questions of identity and belonging.

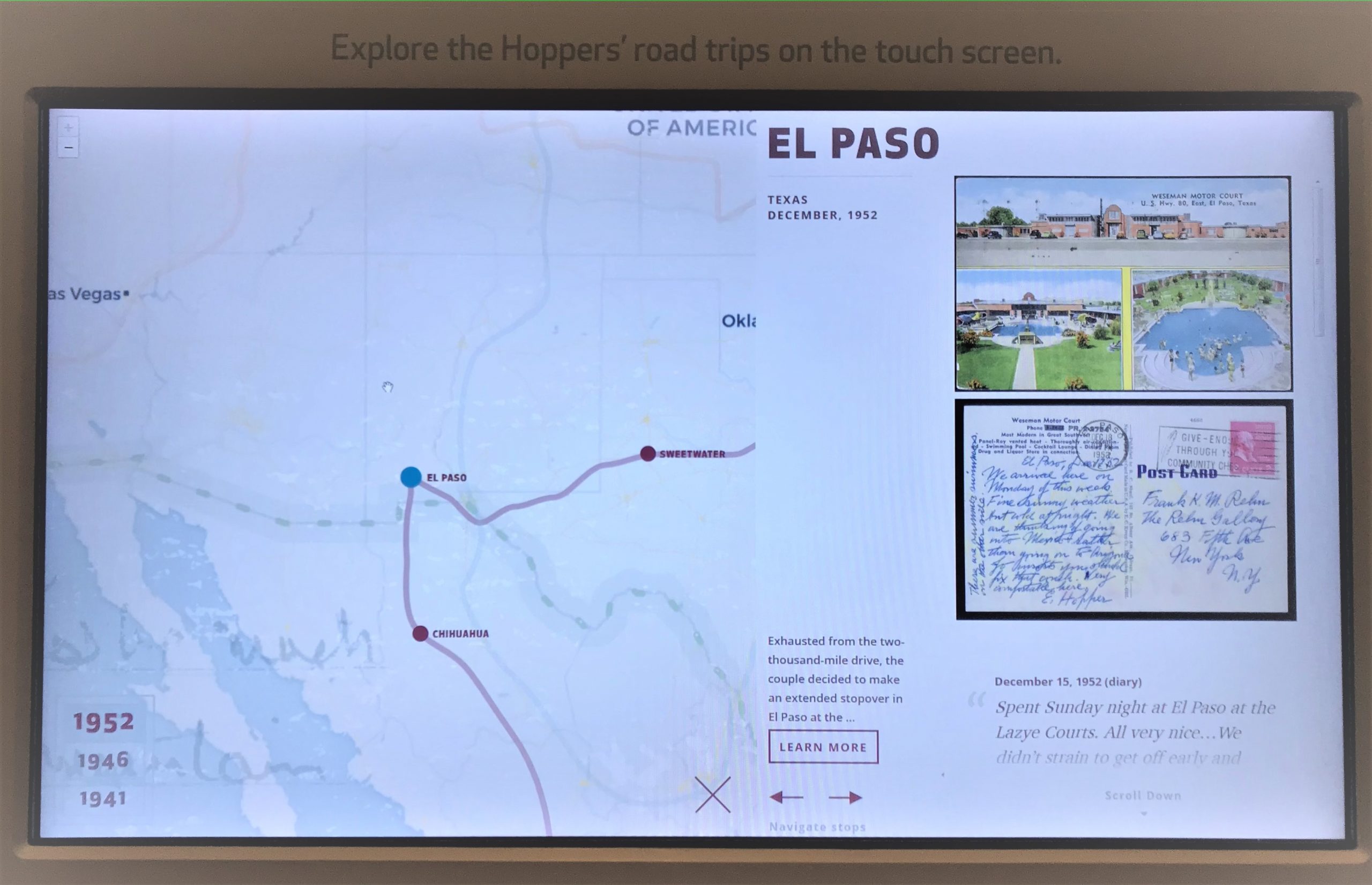

Additional galleries bring together paintings, works on paper, and ephemera from the Hoppers’ travels in Maine, Massachusetts, and South Carolina, as well as their extensive road trips from the eastern seaboard to California and as far south as Oaxaca, Mexico. The exhibition maps three of these road trips in 1941, 1946, and 1952, drawing upon Jo’s diaries, which provide a firsthand account of the motels, sites, and people that she and Edward visited during their travels. Her diaries, several of which are also on view, were recently made available to the public by the Provincetown Art Association and Museum—a clarion call for new analyses of her life and work. Jo was an artist in her own right, although she devoted much of her life’s work to supporting her husband’s career, including helping him hunt for subject matter on the road. An interactive touchscreen, titled “The Hopper Road Trip Experience,” allows visitors to explore Jo’s descriptions and reproductions of related works by Edward (fig. 3). A collection of postcards from the places where the couple stopped is also on view on the opposite wall, offering a sense of motel material culture. The corresponding catalogue includes two inserts by Sarah G. Powers that map the Hoppers’ 1941 “Grand Tour of the West” (to use Jo’s phrase) and their 1952–53 trip to Oaxaca, with an extended stay in El Paso. One hopes this wealth of information might be made permanently accessible online.

Edward Hopper’s vivid watercolors from his time with Jo in Mexico reveal a lesser-known side of his artistic production, further elaborated in Powers’s catalogue essay. Works such as Saltillo Mansion (1943; The Metropolitan Museum of Art) and Monterrey Cathedral, Mexico (1943; Philadelphia Museum of Art) portray Edward’s view from the hotels and guesthouses where they stayed; Jo termed the bird’s-eye perspectives that he deployed in these works “the tower effect.” These perched vantage points allowed him to explore the landscape without interacting with the local community and culture, and as Powers notes, Edward’s initial dislike of Mexico might have motivated, in part, his desire to stay tethered to their hotel (125–28, 131). These ensconced viewpoints are a counterpoint to the unfettered mobility that Hopper seemed to experience in the United States, and they demonstrate an underexplored side of this “quintessential” American artist—Hopper as a foreigner—that should inspire productive future discussion.

Throughout the exhibition, works by other American artists that engage with the hospitality industry punctuate those by Hopper. These comparisons broaden the exhibition’s scope and place issues of identity in the foreground. An introductory room nods to the nineteenth-century development of the hotel in the United States, with works such as Robert Salmon’s Dismal Swamp Canal (1830; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), Richard Caton Woodville’s War News from Mexico (1848; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), and George Henry Durrie’s The Country Inn (c. 1851; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), gesturing toward the wide-ranging typology of early hotels. Paintings of genteel settings by Henry Twachtman and John Singer Sargent are signposts for the rise of leisure culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Lafayette (1928; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), an etching by John Sloan (a good friend of the Hoppers), is displayed alongside Hopper’s etching Night Shadows (1921; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), both prints capturing the visual presence of short-term accommodations in the urban environment. All of these works underscore the multifunctionality of the hotel as a space for the circulation of news, a bucolic escape, or simply a night out.

As the exhibition progresses through its thirteen rooms, the quantity of works by other artists increases, spinning out from Hopper’s sphere into an array of examples from other artistic movements. These examples show how specific architectural forms and themes of fragmentation and connectedness in modern life—particularly in urban settings—were given visual expression through diverse representational strategies. A section on windows, for instance, features works by modernist mainstays such as Alfred Stieglitz and Charles Demuth that both manipulate views in and of hotels. Stieglitz’s From My Window at the Shelton, West (1931; Philadelphia Museum of Art) captures New York City’s midtown skyscrapers and crops out the streets below, showing the new possibilities of physical distance in the city. Demuth’s Rue de singe qui pêche (1921; Terra Foundation for American Art) is a composite scene, including fractured hotel and café signage, that imagines the experience of a Parisian street. Paintings by Stuart Davis and Edward Ruscha augment a gallery on signage, which considers how artists play with the visual language of hotels’ commercial identity.

In some cases, these comparisons might serve as provocations, prompting visitors to consider how issues of race and gender are inseparable from access to and experiences of hotels and the broader built environment. Following the gallery on the Hoppers’ extensive road trips, for example, visitors encounter Derrick Adams’s sculpture Beacon 3 (2018). With its glowing doors and pitched roofs that connote welcome, this work responds to The Negro Motorist Green Book (1936–1967), a publication that listed hotels and sites considered safe for African Americans as they traveled in an era of racial segregation. After exploring the relative freedom of the Hoppers’ itineraries, the invocation of the Green Book calls attention to the whiteness of Hopper’s subjects and spaces, as well as to the artist’s own identity as a white man. Curious visitors can turn to Carmenita Higginbotham’s nuanced catalogue essay, which elaborates on the operation of whiteness in Hopper’s paintings, for more insights. Aspects of her analysis would be a welcome addition to the gallery walls.

Other comparisons set the stage for deeper dialogue on issues of gender, sex, and voyeurism within Hopper’s work. Although these are well-worn topics in existing scholarship on Hopper, they take on a unique valence in the context of the hotel. Art historian Vivien Green Fryd has interpreted Hopper’s works alongside the changing concept of marriage from the 1920s to the 1950s. She notes that the hotel was seen by some in this period as a site of unrestrained sexual encounters and therefore a threat to family stability.1 This interpretation is not explored in the exhibition; however, the inclusion of Hopper’s portrayals of nude women in hotel bedrooms, such as the etching Evening Wind (1921; Williams College Museum of Art), and the painting Eleven A. M. (1926; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution), may make these themes inescapable for some. The exhibition uses a comparison between George Segal’s large-scale sculpture Blue Girl on Black Bed (1976; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) and Hopper’s oil Excursion into Philosophy (1959; Private collection) to discuss more overtly moments of disconnection or romantic estrangement in the hotel room setting. In both of these works, male and female figures are isolated from one another despite their physical proximity in the charged setting of a small bed. The coupling of these two works points to the emotional scenarios that a hotel room might harbor. For additional readings on the subjectivity of Hopper’s figures, Erika Doss’s discussion of the New Woman type of the 1920s and 1930s is of use, as is David Brody’s elaboration on the invisibility of the hotel labor that allowed for these private or reflective settings. Both are in the exhibition catalogue.

Edward Hopper and the American Hotel is an entertaining and enticing exhibition, similar to the potential experience of hotels themselves (indeed, as noted above, it became an accommodation for select overnight guests). But the experience of a hotel is not monolithic—a variety of different encounters with it exist. The diverse works featured alongside Hopper’s serve as a reminder of that fact. This exhibition joins a push in art history to rethink the monographic study by shifting the conceptual framework beyond a singular person’s artistic production, creating an opportunity for new debates to permeate existing narratives. At the same time, it builds on existing themes in Hopper scholarship, including alienation, fragmentation, and depictions of the vernacular built environment in the United States. Through the lens of the hospitality industry, this exhibition expands these lines of inquiry to forge meaningful connections between works of art and the spaces, places, and people they depict, raising powerful questions for academic and general audiences alike. On a more somber note, perhaps in its next iteration, at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, this show will resonate with audiences in new ways as the COVID-19 pandemic forces our society to reconsider how we conceive of isolation and togetherness.

Cite this article: Lee Ann Custer, review of Edward Hopper and the American Hotel, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10048.

PDF: Custer, review of Edward Hopper and the American Hotel

Notes

- Vivien Green Fryd, Art and the Crisis of Marriage (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2003), 1–8, 75–78. See also Carter E. Foster, “The Bedroom,” in Hopper Drawing, ed. Carter E. Foster (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with Yale University Press, 2013), 204–17. ↵

About the Author(s): Lee Ann Custer is a doctoral candidate in the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania