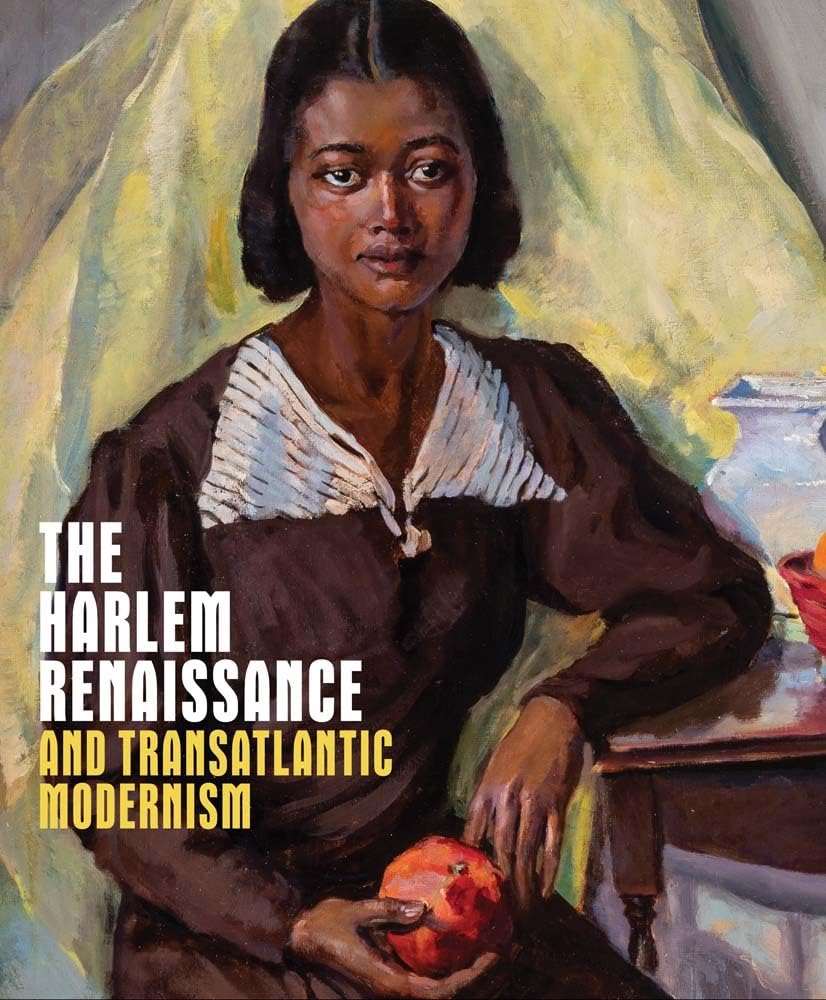

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

PDF: Harakawa, review of The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

Edited by Denise Murrell

Exh. cat. Yale University Press, 2024. 332 pp, 262 color illus. Hardcover: $65.00 (ISBN: 9781588397737)

When the exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in February 2024, it was immediately showered with superlatives: it was “groundbreaking,” a “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity, and a “blockbuster.” This reception reflects both a concerted attempt on the museum’s part to match the enduring popularity of the Harlem Renaissance and a resurgence in art-historical scholarship on the era. Recent publications include multiple books on Alain Locke, the movement’s primary theorist (James C. Stewart’s biography won the Pulitzer Prize in 2019, and Kobena Mercer’s study won the 2024 Frank Jewitt Mather Award from the College Art Association); reassessments of the movement’s global engagements with African art (Joshua I. Cohen’s The Black Art Renaissance: African Sculpture and Modernism Across Continents, 2020); and monographic treatments of individual artists.1 These works enrich a preexisting body of literature across art history, performance studies, literature, and political history that has cemented the preeminence of the Harlem Renaissance in histories of the African Diaspora. What has been missing in recent years, however, is an art-historical reconsideration of the movement in full. This richly illustrated exhibition catalogue—featuring eleven essays by scholars from the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean—sets the stage for such work.

The catalogue’s contents fall into three broad categories: essays that reframe the movement’s canonical figures; essays that expand the movement’s geographic reach; and essays that consider the movement’s reception within museums. A text by exhibition curator Denise Murrell opens the first group. Focusing on how “New Negro” artists reimagined Black subjectivity, Murrell uses debates between Locke and W. E. B. Du Bois to consider how shifting arguments around aesthetics, social uplift, politics, and modernism defined artistic production in the Harlem Renaissance. While Murrell mostly focuses on portraiture, Richard J. Powell, in the another essay, looks to genre scenes, analyzing gambling imagery in the work of Archibald Motley, Aaron Douglas, Palmer Hayden, and Hale Woodruff. Scholarship on the Harlem Renaissance tends to emphasize racial stereotypes, whether artists challenged racist visual tropes or exaggerated them to critical effect.2 Powell rejects this binary, focusing instead on how gambling—a pastime requiring strategies of concealment, bluffing, and tactical revelation—allowed Black people to negotiate various forms of identity. Emily Braun’s essay on the influence of German modernism on Harlem Renaissance aesthetics counters the dominance of Paris in scholarship on the movement’s European reach.3 From Winhold Reiss’s “Harlem types” to the stoic portraits of Motley, Braun draws connections across various discourses of realism, including commercial design, magical realism, and the rhetoric of the New Negro. In her essay on James Van Der Zee, Emilie C. Boone reframes the legacy of the legendary photographer through questions of mobility. Treating the Harlem Renaissance as a “sweeping phenomenon” (75), Boone challenges the photographer’s association with portraiture to claim for Van Der Zee a modernism premised on the mobility of Black photographs and people alike. In his essay, James Smalls shows how the Harlem Renaissance fostered “queer camaraderie” (83), focusing on figures such as Langston Hughes, Richmond Barthé, Bruce Nugent, and Alain Locke. These essays shed new light on some of the Harlem Renaissance’s most canonical figures, but they also attest that any attempts to expand its influence will require interpretive reframing, interdisciplinary methods, and transnational considerations.

While Powell, Braun, and Boone focus on the interaction between transatlantic ideals and artists based in the United States, the second group of essays looks at interactions with the Harlem Renaissance abroad. In her essay on Ronald Moody, Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski traces the life and career of the Jamaican-born British sculptor. Moody’s synthesis of modernist aesthetics with the lessons of African and Mesoamerican art caught the eye of Locke, who included Moody in his 1939 exhibition Contemporary Negro Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art. The appeal of Moody’s work is unsurprising given Locke’s interest in the relationship between the ancestral and the modern. But Moody’s practice also suggests that the ideas that are often ascribed to Locke are traceable to other sources and grounded in diasporic and colonial conditions of existence more generally. In her essay on the Dutch Caribbean, Stephaine Archangel traces commercial and intellectual connections between the islands and Harlem. The trade in Panama hats exposed merchants to the aesthetic values of modernism and the political values of Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanism, which they then adapted to challenge the colonial status quo at home. Christelle Lozére also considers circuits of exchange, focusing on artists working between Paris and the French Antilles in the interwar period. Painters such as Germaine Casse—who sponsored modern art exhibitions in both Guadeloupe and Paris—had to contend with different approaches to representing Black subjectivity as well as an imperialist lens that limited the reception of their work in the metropole.

Together, these essays answer historian Lara Putnam’s call to “provincialize Harlem” and to see the neighborhood as a “frontier” for a “connected Caribbean.”4 Expanding the discourse of migration beyond the Great Migration—a unidirectional and nationally bound narrative—recasts Harlem as indelibly tied to colonialism and the wider diaspora. Thus, these essays do not simply echo critiques of Harlem-centrism that have long dominated scholarship.5 In repositioning histories of the Harlem Renaissance within the diaspora, they also show that the neighborhood’s status as mecca is always dependent on its entanglements elsewhere.

The promise of this approach was what initially excited me about the exhibition, as the “transatlantic” framework suggested that the Metropolitan Museum of Art would craft a narrative commensurate with broader disciplinary emphasis on decolonization and global modernism. When I saw the exhibition, however, I was disappointed by the lack of diasporic representation. With exchange primarily relegated to the United States and Europe, I felt that the “and” in the title linking the “Harlem Renaissance” to “Transatlantic Modernism” conjoined two entities left distinct rather than bridged. The catalogue is then key to the exhibition’s overall success. Delving into forms of connection that the exhibition could not (whether because of space, the availability of loans, or a whole host of other practical concerns), it provides multiple examples of how to redefine the “transatlantic” for the Harlem Renaissance.

Clare Tancons traces these transatlantic connections in her essay on procession, which concludes the catalogue. Looking at various parades in New York—from the 1917 NAACP Silent Parade against lynching to the parades of Garvey’s Harlem-based Universal Negro Improvement Association—Tancons draws unexpected connections across space and time. She pairs, for example, the Harlem Hellfighters from the 1910s with the paintings of Norman Lewis from the 1960s. For Tancons, form is inherently social. A means of congregation, the parade enables new modes of relation, where individual identity is always tied (whether in ways that are constricting or liberating) to the identity of a larger group.

The third set of essays discusses the historicization of the Harlem Renaissance in museums. In her essay, former Met curator Lowery Stokes Sims assesses the museum’s collecting history. Her essay focuses on how the Works Progress Administration (WPA) facilitated the museum’s earliest acquisitions of work by Black artists, a story that challenges the association of the Great Depression with Harlem’s cultural decline. By providing indispensable financial support, the WPA allowed Black artists to make work that could be collected for posterity. Looking beyond the Met, Bridget R. Cooks discusses the three major Harlem Renaissance exhibitions that preceded the show at the Met. Highlighting the broader trend of institutional neglect (the first show took place in 1987 at the Studio Museum in Harlem) and how curatorial approaches have evolved from a focus on a core group of Harlem-based artists to a more expansive approach to geography, race, and medium, Cooks positions the 2024 exhibition as another step in this progression, demonstrating that curatorial approaches to the movement remain very much in flux.

Cooks is also one of the leading historians of the Met’s relationship to Harlem in another context: the 1969 exhibition Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968. Organized by Allon Schoener, then the visual arts director of the New York State Council on the Arts, this show was the museum’s first attempt to build an exhibition around Black history. Harlem on My Mind was immediately controversial because of the lack of curatorial engagement with the Harlem community and the exhibition’s reliance on photographic documentation and exclusion of artworks by Harlem residents. As Cooks writes in her 2011 book Exhibiting Blackness, these choices “reeked of patronizing discriminatory racial politics.”6 Harlem on My Mind is not mentioned in the catalogue. And while it is true that this is well-trodden scholarly ground, the omission is particularly striking given the Met’s institutional history and the exhibition’s final work: Romare Bearden’s monumental collage The Block, which he finished two years after participating in the protests of Harlem on My Mind.7 (The collage, which measures eighteen by four feet, is reproduced in a four-page spread at the end of the catalogue.) Not only does the lack of engagement with Harlem on My Mind feel disingenuous; it is also a missed opportunity to think about the importance of the legacy the Harlem Renaissance left for artists working after the movement, which is the subject of my own research.

Given that the Met emphasized the importance of loans from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in its exhibition promotion, a lack of scholarly engagement with these institutions in the catalogue is also palpable. HBCUs have always been at the forefront of collecting the art of the Harlem Renaissance. And some of the movement’s most accomplished figures taught at these institutions, including Alain Locke, Loïs Mailou Jones, and James Lesesne Wells at Howard University; Hale Woodruff at Atlanta University; and Aaron Douglas at Fiske University. This history reflects yet another limitation of the “Great Migration” frame: it virtually removes the American South (the home of so many HCBUs) from discussions of Black modernity, rendering it a place from which to escape rather than a place to which one might return, whether literally or aesthetically.8 Exploring the afterlives of the Harlem Renaissance in the American South would have been yet another way to expand the movement’s art-historical relevance.

That said, it is unfair to expect one publication or exhibition to assume so much intellectual work. Highlighting these omissions only underscores the richness of the Harlem Renaissance. Hopefully, in the future, art historians can tug at the threads suggested by these various essays, unraveling the histories we think we know about the Harlem Renaissance to continually explore anew why it is one of the most important movements in the history of modern art.

Cite this article: Maya Harakawa, review of The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, edited by Denise Murrell, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 11, no. 1 (Spring 2025), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.19995.

Notes

- Jeffrey C. Stewart, The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke (Oxford University Press, 2018); Kobena Mercer, Alain Locke and the Visual Arts (Yale University Press, 2022); Joshua I. Cohen, The “Black Art” Renaissance: African Sculpture and Modernism Across Continents (University of California Press, 2020); Rebecca VanDiver, Designing a New Tradition: Loïs Mailou Jones and the Aesthetics of Blackness (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020); Renée Ater, Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller (University of California Press, 2011); Emilie C. Boone, A Nimble Arc: James Van der Zee and Photography (Duke University Press, 2023). ↵

- For a discussion of these two positions, see Phoebe Wolfskill, “Caricature and the New Negro in the Work of Archibald Motley Jr. and Palmer Hayden,” Art Bulletin 91, no. 3 (2009): 343–65; see also Richard J. Powell, Going There: Black Visual Satire (Yale University Press, 2020). ↵

- The major work here is Theresa A. Leininger-Miller, New Negro Artists in Paris: African American Painters and Sculptors in the City of Light, 1922–1934 (Rutgers University Press, 2001), but also influential is Brent Hayes Edwards, The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism (Harvard University Press, 2003), which anticipates the “transatlantic” frame of the 2024 exhibition, focusing primarily on the francophone and anglophone African diaspora. ↵

- Lara Putnam, “Provincializing Harlem: The ‘Negro Metropolis’ as Northern Frontier of a Connected Caribbean,” Modernism/ Modernity 20, no. 3 (2013): 469–84. ↵

- See, for example, Davarian L. Baldwin and Minkah Makalani, eds., Escape from New York: The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem (University of Minnesota Press, 2013). ↵

- Bridget R. Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), 53. ↵

- See Caroline V. Wallace, “Exhibiting Authenticity: The Black Emergency Cultural Coalitions Protests of the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1968–71,” Art Journal 47, no. 2 (2015): 5–23. ↵

- Recent attempts to rectify this exclusion include the exhibition and catalogue Southern/ Modern: Rediscovered Southern Art from the First Half of The Twentieth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2023). ↵

About the Author(s): Maya Harakawa is assistant professor in the Department of Art History, University of Toronto.