Horace Pippin, American Modern

by Anne Monahan

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020. 264 pp.; 96 color + 25 b/w illus. Hardcover: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780300243307)

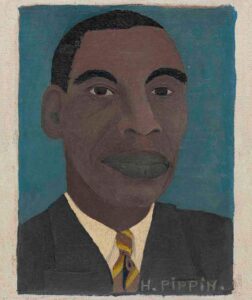

On June 2, 1946, Abstract Expressionist Ad Reinhardt’s art comic How to Look At Modern Art in America appeared in the pages of New York’s PM magazine with a caption that began, “Here’s a guide to the galleries—the art world in a nutshell.” The cartoon depicted the modern art world as a sprawling, leafy tree. The leaves contain names of artists grouped on branches weighed down by various styles and influences. Self-taught painter Horace Pippin (1888–1946), perhaps the most well-known African American artist of the period, is represented not as a leaf but as a bird flying above the tree in the upper right. Within the contemporary art world of the 1930s and 1940s, curators, collectors, and critics celebrated so-called “modern primitives” like Pippin. His position within the image is significant. Pictured as the lone bird in flight, Pippin is an artist on the modern art scene but outside it, at a distance. Reinhardt’s illustration is the final page in Anne Monahan’s new book Horace Pippin, American Modern. In her interpretation of the cartoon, Monahan writes, “Pippin’s avian avatar is free to alight anywhere . . . a model that frames his distance as agency, not exile” (206). Recouping Pippin’s agency and unpacking his relationship to the art world of the 1930s and 1940s guides Monahan’s scholarly endeavor. Horace Pippin offers a welcome and necessary counter to the well-worn “discovery narrative” scholars so often use when discussing the artist. Notably, this well-researched study challenges the continued classification of Pippin as a naïve outsider artist, expands our understanding of modern art in the United States, and unequivocally demonstrates that Pippin’s work can withstand “the range of standard interpretive methodologies” reserved for those “mainstream” artists who populate Reinhardt’s tree (2).

During World War I, Pippin served in the famed all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment, also known as the Harlem Hellfighters. While deployed in France, he sustained a severe injury to his right arm, leaving him permanently disabled (9). Following his rehabilitation and discharge, Pippin’s path to a painting career began with a pastime decorating cigar boxes. In the 1920s, he started burning designs into wood panels. Frequently, this shift in artistic method is regarded as therapy for his wounded arm. Pippin was in his forties when he began painting on canvas in the 1930s. Over the next fifteen years, he completed at least 140 paintings on themes that ranged from war scenes to domestic interiors, cotton plantations, biblical stories, history paintings, portraits, and flowers. In 1937, his first formal exhibition took place in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was born and had returned to after his military service. This local exhibition led to national attention, with renowned artist N. C. Wyeth and art critic Charles Brinton championing Pippin. The following year, the artist made a splash in the New York art scene when curators selected his work for the Museum of Modern Art’s Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America. Pippin’s inclusion in MoMA’s exhibition changed his circumstances—he went from exhibiting in storefronts to museums and galleries, and he began selling his work to major national and international collectors.

The short duration and meteoric rise of Pippin’s artistic career lends itself admirably to Monahan’s “microhistorical analysis” of the artist’s body of work. In Horace Pippin, Monahan seeks to upend notions of “the audiodidacts’ putative transparency” and to offer an interpretive model that counters the typical biographical lens through which scholars have ignored or minimized the artist’s agency (2). Leveraging intelligent and well-supported close readings of Pippin’s paintings, Monahan reorients interpretation from his life details to his actual artistic production. Her larger objective is “to destabilize an art-historical caste system that has often consigned autodidacts, especially those of color, to treatments that do not fully reckon with the substance of their work” (2).

Through four lengthy chapters organized around the themes of autobiography, labor (specifically Black agricultural labor), process, and gift exchange, Monahan presents a series of compelling arguments that highlight the savvy with which Pippin approached his artistic practice and the agency he exerted throughout his career. She points out how scholars and critics have thus far overlooked his agency and calls out how “‘racecraft’ . . . the process whereby racist ideas become codified as supposedly neutral facts via repetition and publication,” has shaped the critical reception of Pippin and his oeuvre (18). Monahan is self-aware that her monograph, like those that preceded her and those that will come after, “is a time capsule of conceptions of and about race and class” (19).

Monahan’s project is timely, especially her reframing and repositioning of Pippin within the canon of American art. The emergence of new archival material and records related to Pippin uncovered by Monahan and others, along with recent scholarship in the field of self-taught artists, “opens up opportunities to reconsider modernism’s symbiotic relationship to its supposed others” (5). The first chapter, “Autobiography,” parses how Pippin constructed his biography in autobiographical writings from the 1920s onwards. Monahan does not take Pippin’s writings as fact. Instead, comparing Pippin’s statements to each other and to the historical record, she illuminates how Pippin elided history when he saw fit. Monahan suggests “that Pippin understood history, including his own, as malleable” (30). Recognizing Pippin’s autobiographical revisions is important because scholars have relied heavily on these same writings to establish an account of his life, which in turn has colored the interpretation of his paintings. For instance, when excerpts of Pippin’s writing were included in MoMA’s 1938 Masters of Popular Painting, “his unpolished writing style [marked] his distance from the institutional art world and [conditioned] a reception that has emphasized his life story, usually related in his own words, as the primary point of access for his art” (32). The chapter’s second half includes Monahan’s analysis of Pippin’s war and genre paintings alongside his self-constructed history. These close readings bolster the chapter’s claims about “the pitfalls of biography” by exposing the contradictions and the friction that exists between the truth value accorded to artists’ words when their art and/or historical record tells a different story (5). Monahan leans into Pippin’s inconsistencies and posits the “slippage between autobiography and biography” as critical to understanding his agency and ongoing self-fashioning (23).

“Labor,” the second chapter, explores Pippin’s complicated depictions of Black agricultural labor in his cotton-plantation paintings from the 1930s and 1940s. These paintings of rural Black workers resulted in his “discovery” by the art world and the subsequent “increasing demand for his own artistic labor” (71). Largely well-received, these plantation images were frequently misinterpreted as nostalgic when, in fact, Pippin’s investment in the theme moved from documentary to critical to elegiac. Monahan, through the use of close readings, criticism, and related visual culture, argues that Pippin navigated “uneasily between resistance and accommodation in his recursive attention to black labor” (73). She pairs her discussion of Pippin’s labor paintings with an examination of how he negotiated rising demands for his own labor—applying for grants, signing with Edith Halpert’s modernist Downtown Gallery, and accepting commissions in the 1940s—as he pursued a mainstream audience of collectors, critics, and curators.

In the third chapter, “Process,” Monahan investigates Pippin’s working methods and sources and illuminates how flexibility, influence, and entrepreneurship inflected the artist’s creative practice. Here Monahan stages an essential intervention into Pippin’s widely heralded categorization as a memory painter and “primitive” without outside influence or knowledge of Western artistic traditions. Pippin fueled this classification, telling people “pictures just come to my mind” (6) and being “cagey about his influences” (138). Yet, as Monahan proves in her chapter “Autobiography,” Pippin shaped his history to suit his career goals. Challenging the idea that self-taught so-called primitive artists were without influence, the chapter offers a wealth of new research and compelling visual imagery that shows how Pippin regularly drew “from published images and texts” as well as his cognizance of art-historical peers and precursors (138). Throughout, Monahan warns against the tendency to privilege text over image within Pippin studies, “a predisposition that can garble his critique” (137).

“Gifts,” the final chapter, explores how Pippin nurtured his expanding patronage networks through “symbolic (noneconomic) exchange” (6), which advanced his career as the recipients of his gifts paid him back through exhibition opportunities, sales, and more (196). Informed by Pierre Bourdieu’s gift theory, Monahan focuses her attention on tracing Pippin’s gifting within two cohorts: first, the Black community in West Chester prior to his embrace by the art world and, second, socially prominent white women in the Main Line suburbs of Philadelphia, among them Jane Hamilton and the Winsor sisters, whom he befriended after his rise to acclaim (158). Pippin’s gifts “gave him entrée into social and domestic spaces,” which would have been otherwise off-limits to a Black man (197). In line with the rest of Horace Pippin, “Gifts” suggests ways in which Monahan’s scholarly approach could be applied as well to Pippin’s contemporaries in order to “shift our sense of their creative projects” (197). Monahan uses her short conclusion to situate Pippin staunchly within the 1940s avant-garde by discussing his involvement with art collector Albert Lewin’s competition and exhibition for The Private Affairs of Bel Ami. She reminds her reader that recognizing Pippin’s agency is critical to unraveling the racecraft that has marred his reception.

Offering an exciting scholarly model for “understanding how artists who begin their careers at considerable remove from the art world can close that distance,” Horace Pippin, American Modern makes a substantial and crucial contribution to single-artist studies on African American and self-taught artists (5). As such, the book offers an exciting methodological model that will be of great use to graduate students and specialists in the fields of African American, American, and self-taught/folk art, and it offers a vital contribution to the discipline as a whole as scholars continue to reckon with race in art history.

Monahan is so familiar with Pippin’s oeuvre, associated criticism, and later scholarship that she sometimes relies on art-historical shorthand that requires extensive background knowledge from the reader. Accordingly, the heady chapters make her text less approachable for undergraduates. Students and advanced scholars alike will, however, appreciate that the volume is lavishly illustrated and that the appendix includes a thorough exhibition history, a complete list of extant artworks, and a selection of the artist’s statements, which will spur future study. Monahan sets a new standard for Pippin scholarship by expanding significantly beyond the corpus of extant literature. She offers correctives where needed but also raises questions for other scholars to consider further.

Cite this article: Rebecca VanDiver, review of Horace Pippin, American Modern, by Anne Monahan, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 2 (Fall 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.12872.

PDF: VanDiver, review of Horace Pippin, American Modern

About the Author(s): Rebecca VanDiver is Assistant Professor of African American Art at Vanderbilt University