In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969

Curated by: M. Rachael Arauz and Diana Jocelyn Greenwold

Exhibition schedule: Portland Museum of Art, ME, May 24–September 8, 2019; Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI, December 14, 2019–March 8, 2020

Exhibition catalogue: M. Rachael Arauz and Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, eds., In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969, exh. cat. Portland, ME: Portland Museum of Art in association with the University of California Press, 2019. 192 pp.; 196 illus.; Hardcover $55.00 (ISBN: 9780520299696)

Borrowing the words of Francis Merritt, the first director of the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, the title of the Portland Museum of Art exhibition, In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969, defiantly flouts the longstanding misconception that the avant-garde is an exclusively urban phenomenon. Now that art historians have widely challenged the dominance of New York and Paris on the development of a singular modernism, exhibitions such as this one are free to position such rural art communities as pivotal nodes in a richer, denser narrative of multiple modernisms that bridge rural and urban, local and global, craft and fine art. Cocurated by independent curator M. Rachael Arauz and the Portland Museum of Art’s Associate Curator of American Art Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, this research-driven exhibition is the first sustained project to consider the robust contributions of this Maine institution to midcentury American modernism. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue chronicle Haystack’s early history through the Studio Craft Movement of the 1950s and into the sociopolitical upheavals of the 1960s. During these years, Haystack served as a hub for nationally and internationally renowned students and educators to address themes and materials that were of local importance to Maine and of broader significance to 1960s counterculture, such as communal living, freedom of expression, and the fusion of art, life, and the natural environment.

If Merritt’s phrase frames the exhibition textually, the curators’ subtle display of choices frame it visually. In the galleries, emerald walls impart the glow of the forest and seaside. Underfoot, the museum’s finely crafted wood-grained and granite floors reinforce Haystack’s wide-reaching aesthetic impact on Maine’s built environment, as if they were custom-made for the exhibition. A collage of archival photographs at the entrance, along with faded blow-ups strategically scattered throughout the exhibition, transport visitors to the midcentury sites and studios outside Liberty and, later, at Deer Isle, Maine. Besides representing a common time and place, these images also share another feature—hands (fig. 1). They depict hands teaching and lecturing, tying and weaving, shaping and building, or folded and listening. The afterimages of these active fingers remain in one’s mind as they are visually imprinted onto the textured surfaces of the surrounding objects that they originally shaped.

These objects are organized in the galleries along overlapping thematic and chronological lines. Two section labels mark key historical shifts: “The 1950s: Haystack Begins” and “The 1960s: Haystack Flourishes.” Other didactics highlight media such as fiber and studio glass, while still others emphasize the importance of Haystack’s bucolic surroundings, as in “The Forest and the Sea: Artists and the Environment at Haystack” and the “Centennial House and Gallery.” Far from limiting the interpretation of the works, these categories serve as prompts for considering objects across the exhibition. For example, Robert Ebendorf’s rock casts and dried urchins, Emily Mason and Wolf Kahn’s Abstract Expressionist landscape paintings, and Ted Hallman’s trees appear in different areas of the exhibition yet can all be contextualized through the wall text that stresses the influence of Maine’s forests and shores on Haystack’s artists.

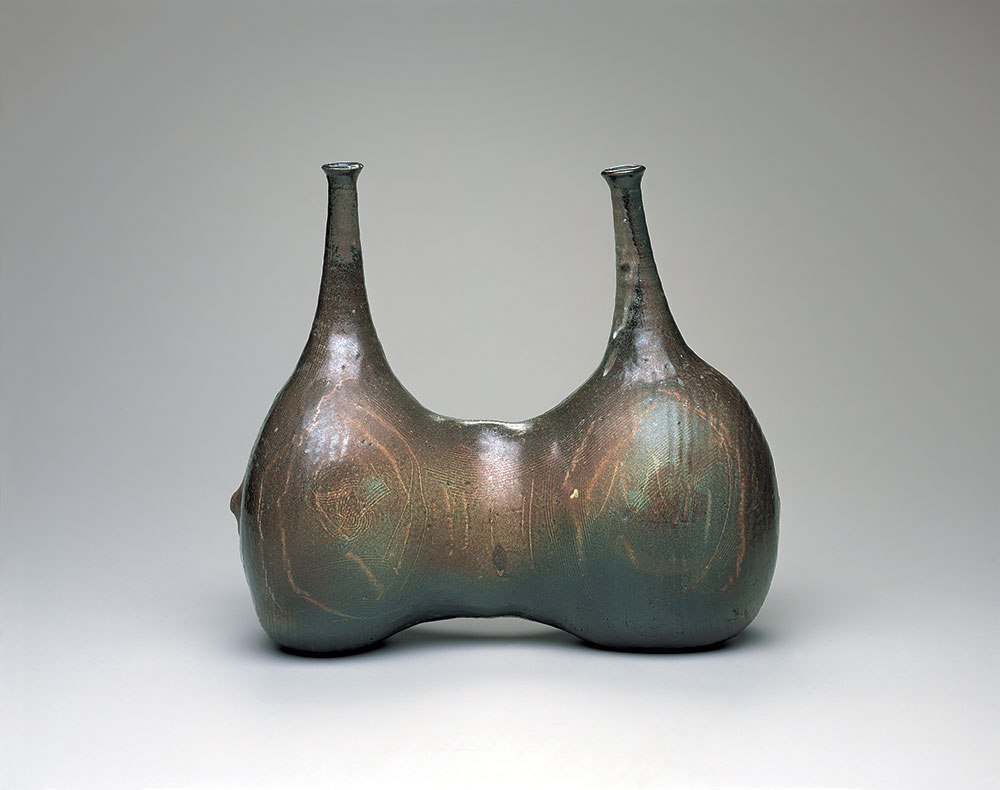

The curators have cultivated thoughtful juxtapositions such as these throughout the galleries to inspire viewers to reimagine possible conversations between the artists and to construct new connections of their own. An example of this can be found on one of the first walls of the show, where the black-and-white graphic quality of Hodaka Yoshida and Antonio Frascini’s prints are echoed in Kay Sekimachi’s weaving, the bulbous onion forms of which chime, in turn, with those of Toshiko Takaezu’s clay double-vessel (figs. 2, 3). The interactions of these diverse forms across media illuminates Merritt’s belief in the interrelationship of all modes and materials.

In this regard, the presentation of the exhibition embraces the same principles as Haystack itself. The curators do not simply present content related to Haystack; they enact its values in their own curatorial process, thereby enhancing the audience’s understanding of the school’s mission. As Greenwold expounds in her catalogue essay, Haystack has always striven to be an inclusive community that challenges hierarchies of medium, age, gender, and expertise. Accordingly, the installation democratically presents works by recently rediscovered figures, such as Haystack founders Mary Beasom Bishop and Elizabeth Crawford, alongside major personas, such as Anni Albers, Robert Arneson, Dale Chihuly, Trude Guermonprez, M. C. Richards, Jack Lenor Larsen, Kay Sekimachi, Toshiko Takaezu, and Stan VanDerBeek. Although each label helpfully states the artist’s role as teacher or pupil—along with the dates they attended Haystack—all are exhibited with equal weight.

Additional historical context can be found on a timeline that encircles a small, enclosed side gallery. Major milestones in Haystack’s history are positioned against key national developments in craft history, evidenced by public relations material, architectural drawings, and other archival ephemera. Quarantining the timeline in this way keeps the visitor focused on the direct encounters with physical objects that are so important in craft. It also resists the common curatorial tendency to overwhelm the viewer with archival research—a particularly widespread pitfall for ambitious shows aiming to reposition a previously underserved topic such as this one.

Instead of overwhelming their audience, Arauz and Greenwold seem to be more interested in educating them—a goal well-suited to an exhibition on a craft school. The pedagogical orientation of the exhibition extends into the scholarly catalogue, whose main essays are broken down following the same chronological periodization as the galleries. First, Steffi Ibis Duarte introduces the founders of Haystack and their sources of inspiration in Flint, Michigan. In so doing, she lays important groundwork for the exhibition to travel to Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, following its Portland presentation. Arauz covers the decade of the 1950s, chronicling the school’s evolving mission and growing national reputation in the Studio Craft Movement. The school’s public ideas and the behind-the-scenes politics of the board form two parallel narratives during this time. Turning to the 1960s, Greenwold covers “a decade marked by tremendous social upheaval and artistic experimentation in abstraction, performance art, and social practice” in which “Haystack gathered diverse and profoundly varied practitioners to learn from one another away from urban centers.”1 She traces the expansion of the curriculum into new media, including found objects, jewelry, performance, and glass, underscoring the role of Haystack in shaping the Studio Glass movement in the United States. From fiber to ceramics, a recurring theme is how the faculty of each medium encouraged a range of approaches, from experimental to traditional and commercial to formal. Finally, a comprehensive gallery of plates captures the textures and materiality of the exhibited objects and shares these never-before-exhibited works with an even wider audience.

As an ambitious reexamination of an experimental, regional art colony, In the Vanguard joins recent efforts such as Slab City Rendezvous at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine (through February 9, 2020); The Craft School Experience: Outcomes and Revelations at the Craft in America Center, Los Angeles (January 21, 2017–March 11, 2017); and Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933–1957, curated by Helen Molesworth for the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (October 10, 2015–January 24, 2016; reviewed in Issue 2.2 of Panorama). The centennial of the Bauhaus, where many early Haystack faculty members worked and studied, has also spurred a spate of exhibitions and publications worldwide. Commentators may overemphasize the similarities of these diverse schools, particularly Black Mountain College, which presents itself as a convenient, high-profile cornerstone by which to comfortably situate less familiar material.2 Arauz contests this tendency early in her essay by announcing that Haystack “was in no way beholden to the influence of earlier models . . . they played no part in his [Francis Merritt, the director’s] conceptualization of the school’s emerging national role.”3 Yet Arauz also observes that “Haystack’s first few years manifested a tangle of disparate connections as geographically and pedagogically diverse as Cranbrook, Penland, Black Mountain College, and Pond Farm as well as the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, the University of Delaware, and the Massachusetts School of Art (now Massachusetts College of Art and Design).”4 The authors of In the Vanguard devote much of their text to reestablishing the complex web of relationships that link Haystack instructors, students, and benefactors to other craft school experiences, revealing the interconnectedness of these institutions. One of the most significant achievements of In the Vanguard is its ability to protect the autonomy of individual artists while recognizing their symbiotic participation in overlapping circles of the Haystack learning community, a broader network of craft institutions and patronage, and ideas about nature, community, and utopia that transcended the art world.

What unites these recent exhibitions, then, is not necessarily similarities between the institutions themselves, but instead a shared contemporary scholarly interest in historicizing, differentiating, and promoting the twentieth-century craft and art school experience. Why do these topics resonate so strongly today? With its interdisciplinary curriculum that incorporated art, history, music, philosophy, writing, theater, and culinary arts, Haystack’s values presage current pedagogical trends toward interdisciplinarity and experimental, community-based instruction. The recent threatened or actual closure of small art and craft schools—notably the Oregon College of Art and Craft in Portland, Oregon—and experimental rural colleges such as Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, and Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont, add urgency to these discussions. Remembering the early years of Haystack simultaneously satisfies nostalgia for idealized, disappearing modes of learning as well as hope for rediscovering pathways to reform higher education into a more sustainable, humane industry.

While indirectly invoking these topical contemporary issues, Arauz and Greenwold largely downplay another hot-button issue in current scholarly conversations —the debate between fine art and craft. Few of their wall texts reference this tired argument, confidently presenting the body of work on its own terms without apology. Such an approach is rare in shows comprised largely of craft objects, especially a summer blockbuster like this one that is presented in a fine arts space as opposed to a dedicated craft gallery or museum. Once again, the curatorial decision not to dwell on the art/craft hierarchy appears to be informed by the values of Haystack itself, which posed the relationship between art and craft media less as a question and more as an essential prerequisite for artistic innovation. In following the school’s example, In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969 encourages a new wave of scholarship that explores other more interesting and pressing questions of community, nature, and the ultimate purpose of an arts education. By presenting a comprehensive overview of the decisive first decades of the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, this exhibition lays the foundation for further study on this underserved topic and models an example for rediscovering the role that other rural organizations across the country may have played in the development of American modernism.

Cite this article: Sarah Parrish, review of In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969, Portland Museum of Art, Maine, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 2 (Fall 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.2220.

Notes

- Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, “Inscriptions in History: Haystack, 1961–69,” in M. Rachael Arauz and Diana Jocelyn Greenwold, eds., In the Vanguard: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1950–1969, exh. cat. (Portland: Portland Museum of Art in association with the University of California Press, 2019), 67. ↵

- See discussion on Critical Craft Forum, “In Maine, A Persistent Vision Amid the Pines,” accessed June 22, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/groups/310882667610/. Response to Murray Whyte, “In Maine, A Persistent Vision Amid the Pines,” Boston Globe, last updated June 23, 2019, https://www.bostonglobe.com/arts/art/2019/06/22/portland-persistent-vision-amid-pines/qkwmNhFSgZWR3UNdkHtxLL/story.html?event=event25&fbclid=IwAR19CNN4SPOXIp_Qb-PrhhwKhe61oJk_QYdaYOXR38svFamlalyldeOL0iQ. ↵

- M. Rachael Arauz, “The Best Ideals of Socially Useful Living: Haystack, 1950–60,” in Arauz and Greenwold, eds., In the Vanguard, 27. ↵

- Arauz, “The Best Ideals of Socially Useful Living,” 27–28. ↵

About the Author(s): Sarah Parrish, Assistant Professor and Program Coordinator of Art History, Plymouth State University, New Hampshire