Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map

PDF: Vázquez de Arthur, review of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Curated by: Laura Phipps, Assistant Curator, Whitney Museum of American Art

Exhibition schedule: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 19–August 13, 2023; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, TX, October 15, 2023–January 7, 2024; Seattle Art Museum, February 15–May 12, 2024

Exhibition catalogue: Laura Phipps, ed., Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, exh. cat. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2023. 264 pp.; 180 color illus.; 15 b/w illus. Hardcover: $65.00 (ISBN: 9780300269789)

Last spring, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York launched a traveling retrospective exhibition showcasing the work of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b. 1940), a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation. The most extensive exhibition of Smith’s work to date, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map pays tribute to the lifelong career of an artist who was told early on that women could not be artists and who saw no examples from art history that reflected her lived experience or perspective as an Indigenous American.1 Faced with few opportunities to exhibit her work as an emerging artist, Smith found that she had to assume the additional roles of curator, educator, advocate, and activist in order to succeed in the art world. Even now, Smith continues to organize exhibitions for Native American artists, including the National Gallery’s first artist-curated exhibition, The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans, currently on view.2 The Whitney Museum’s retrospective exhibition brings together more than 130 artworks and related ephemera that trace the evolution of her career as an artist and organizer. In the spirit of Smith’s collaborative inclinations, the exhibition is accompanied by an audio guide that features commentary by several Indigenous artists and scholars who further illuminate the powerful messaging in Smith’s work.

Upon entering the fifth-floor gallery at the Whitney Museum, visitors to the exhibition are greeted by an expansive triptych titled Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights (2015; fig. 1). It is the first of many trade canoes that visitors encounter in the exhibition, and it serves as an introduction to Smith’s bold use of icons as part of an expressive and meaningful visual language. In this work, bearing a title that references a biblical narrative of apocalyptic destruction, the trade canoe becomes a life raft for what might be saved of Indigenous culture in the aftermath of European invasion. According to artist Andrea Carlson (Grand Portage Ojibwe), “In this vessel, the things that are being saved are beings, they are spirits, they are stories. I love how at the center of this piece, Coyote emerges, Coyote as a central character with these bright beams behind him.”3 Smith uses the trade canoe icon as a signifier for confrontation between Indigenous Americans and European colonizers, often filling the canoes with items that are vulnerable to being lost or stolen or that serve as references to the toxic effects of colonization on Native American communities.

Smith began her Trade Canoe series in 1992, a year that marked the quincentennial anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s fateful voyage across the Atlantic. Although Smith’s artistic practice had long focused on Native American perspectives, her desire to speak out and be heard intensified in the face of national celebrations that glorified the mass genocide set in motion by Columbus’s landing in the Caribbean. From the early 1990s, Smith began to engage more directly with semiotics, reorienting her work around a powerful iconographic vocabulary that she employs to dispel stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples and to combat Eurocentric narratives about the colonization of North America.

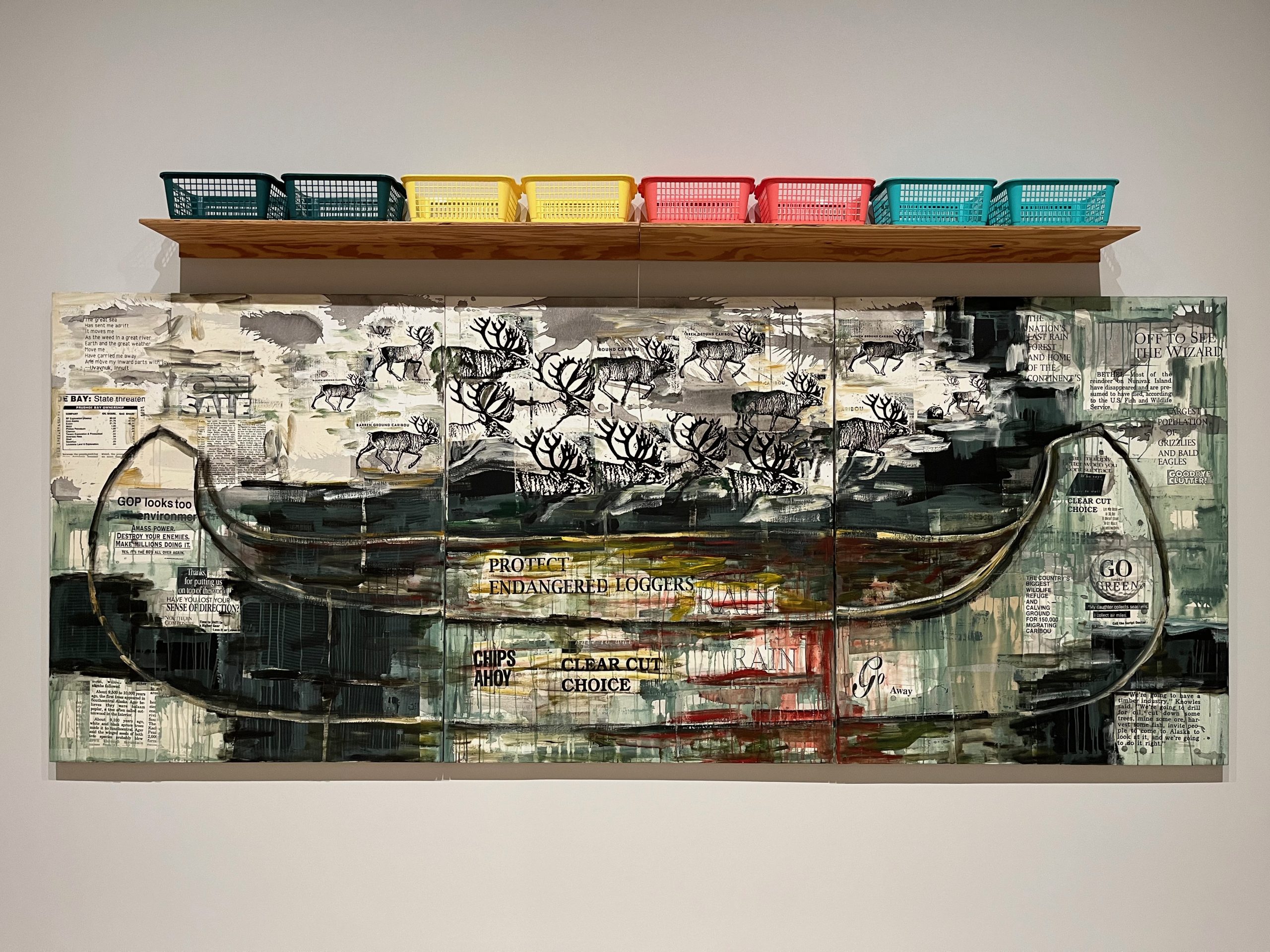

Trade canoes recur throughout the exhibition, as they do throughout Smith’s nearly fifty-year career. Entering the exhibition, visitors pass through a brief display of Smith’s early work from her time as a graduate student at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Beyond this introductory gallery, the exhibition broadens, allowing museumgoers to follow their own paths through a viewing experience that is arranged thematically rather than chronologically. Paintings from Smith’s Trade Canoe series—each filled with a different assortment of items—act as waystations throughout the exhibition, guiding visitors from one section to another. Just past the introductory gallery, a second canoe, Tongass Trade Canoe (fig. 2), becomes a gateway into a section of paintings that emphasize a concern for environmental protection. The title refers to the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, a temperate rainforest that is vital to the procreation of the barren-ground caribou, pictured above the canoe as a herd of collaged photocopies. Inside the otherwise empty canoe, large letters exclaim “Protect endangered loggers,” a tongue-in-cheek reference to the devastating practice of clearcut logging of old-growth trees at Tongass. With clearcut logging, all the trees from an area are cut down at once, threatening the extinction of many species, including the barren-ground caribou. Although a ban on logging and the building of roads was established in 2001, it was repealed by the US government in 2020.4 More recently, in early 2023, the current administration reinstated the ban on logging and road building in the Tongass; however, the protection of this precious natural resource remains vulnerable to changing trends in government administration.5

Near Tongass Trade Canoe, a group of paintings known collectively as the Chief Seattle series likewise speaks to Smith’s commitment to environmental activism. These earlier works predate Smith’s incorporation of textual fragments clipped from media headlines that became integral to her work after 1992. In Sunlit (C.S. 1854), Red Cross (C.S. 1854), and The Garden (C.S. 1854), all produced in 1989, Smith uses text for the first time in her paintings when she includes quotations from a speech by Squamish and Duwamish leader Chief Seattle in March 1854. While the text in these works is hand-painted rather than collaged, Smith additionally incorporates three-dimensional objects into these works, making meaning through the intersection of image, text, and object in a way that anticipates her later use of collage and iconography as visual language. According to artist and writer Gail Tremblay (Onondaga and Mi’kmaq), “These pieces combine words expressing Native thoughts about the natural world and visual objects to make viewers think about the way industrial practices endanger the environment.”6

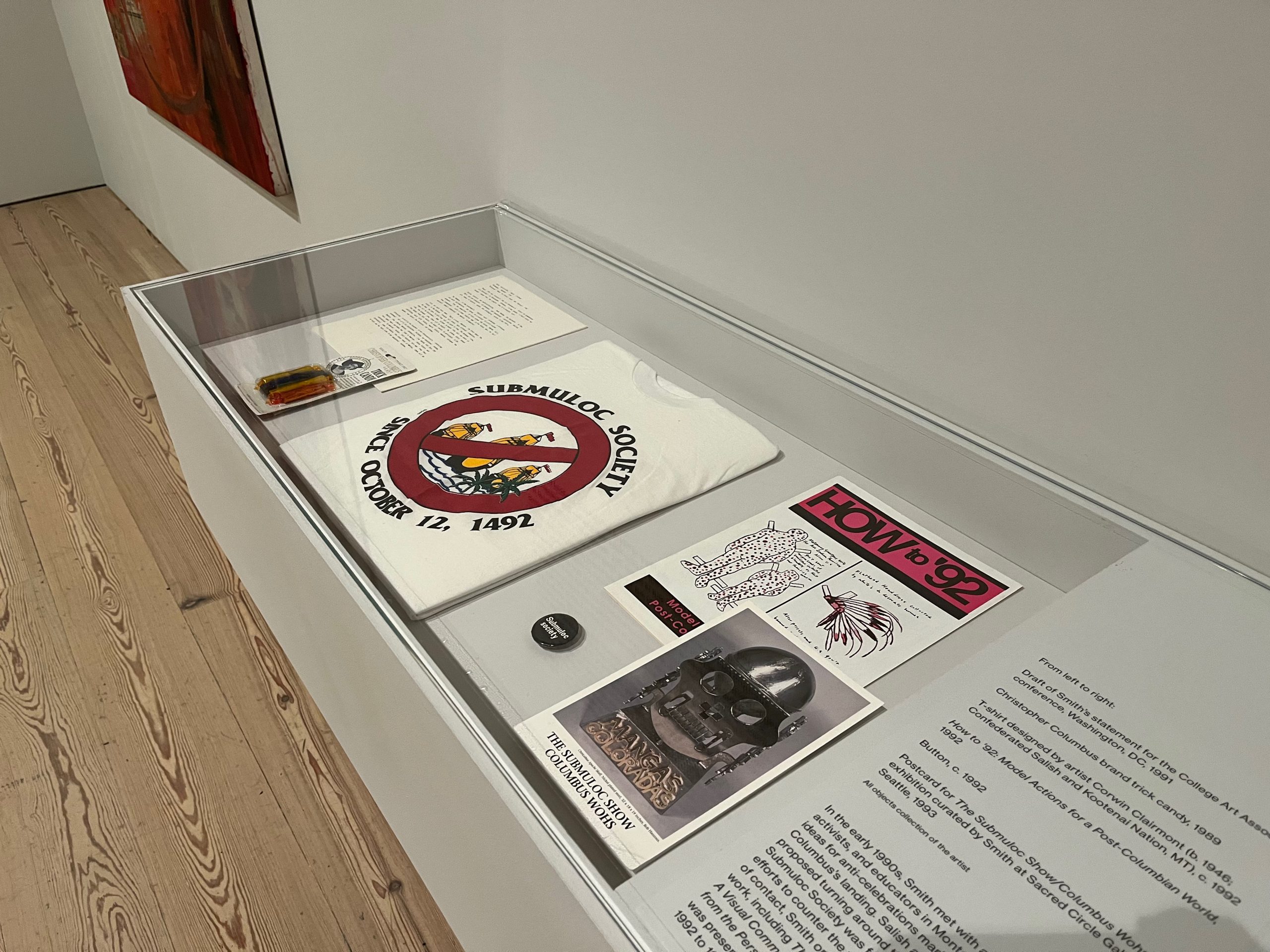

Smith’s artistic practice is inseparable from her work as an activist. Most, if not all, of the exhibition’s thematic sections can be viewed as aspects of Smith’s activism in support of a range of issues that are particularly important to Indigenous Peoples and communities, including her work in organizing and promoting exhibitions of contemporary Native American artists across the United States. Ephemera from Smith’s own collection gives testimony to the many campaigns in which she has participated, including her work with the Friends of the Albuquerque Petroglyphs to establish the Petroglyph National Monument in New Mexico and her role as a cofounder of the Submuloc Society Since 1492, a group of artists, activists, and educators committed to counteracting Eurocentric narratives around the colonization of North America (fig. 3). The word Submuloc is Columbus spelled backwards, and the Submuloc Society came together in the years leading up to the 1992 quincentennial of Columbus’s landing. Its primary goal was to organize anticelebrations of the five-hundred-year anniversary. Among the items on view in the exhibition are a Submuloc Society t-shirt designed by Corwin Clairmont (Salish and Kootenai), a pamphlet titled “How to ’92: Model Actions for a Post Columbian World” (1992), and a postcard for The Submuloc Show / Columbus Wohs, an exhibition that Smith curated, which included work by more than forty Native American artists and toured throughout the United States from 1992 to 1994.

Although trade canoe paintings continue to appear throughout the exhibition’s many sections, the canoe is just one of several items that Smith mines for semiotic value. American flags and maps of the United States are other recurring themes in several paintings, and they likewise serve as devices for contemplation and analysis. Two American flag paintings, Green Flag (1995) and McFlag (1996), are both striking examples of what curator Laura Phipps describes on the museum label as “a biting critique of American capitalism and consumerism.” Painting these works four decades after Jasper Johns’s Flag (1954–55; Museum of Modern Art), Smith engages directly with Johns’s choice of subject matter but pushes the conversation in a new direction. Whereas Johns appropriated readymade symbols like flags, maps, and targets as banal allusions to daily life, Smith embraces the political symbolism of the flag to highlight correlations between patriotism and greed in the modern American lifestyle. Moreover, the scraps of printed media that she incorporates into both Green Flag and McFlag are carefully selected, combined, and intentionally legible, amplifying the meaning and clarity of her message.

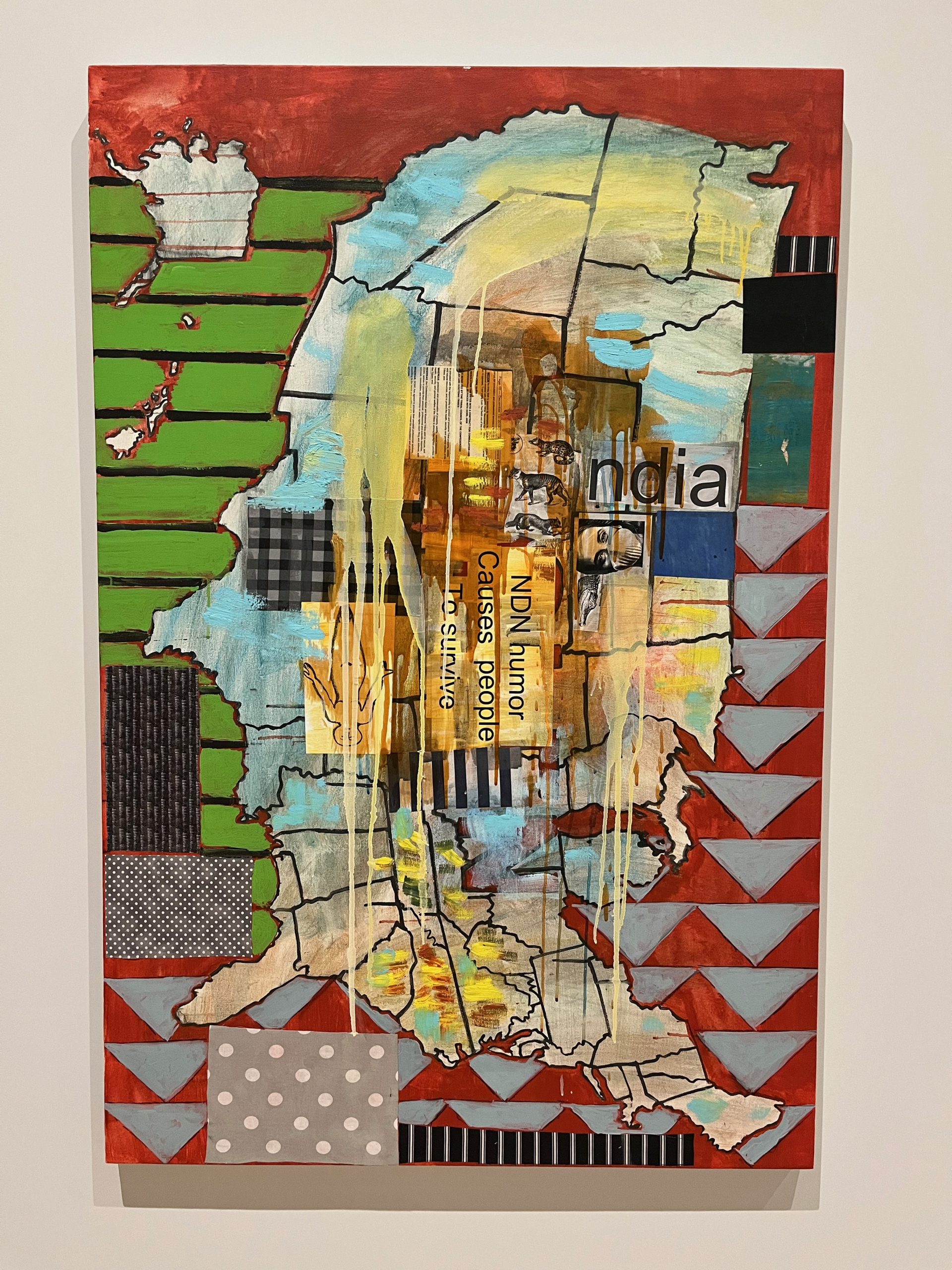

Smith’s paintings of maps, particularly those from the 1990s, can likewise be compared to Johns’s Map (1961; Museum of Modern Art) with their loose, dripping brushstrokes and use of color blocking to roughly demarcate state boundaries. Yet these formal similarities again fall short of any meaningful comparison between the two artists. As curator and art historian Richard William Hill (Cree) writes in his essay for the exhibition catalogue, “In Smith’s handling of these subjects there is a stylistic similarity [to Johns], but we are directly challenged to read the signifiers from an Indigenous perspective, through which they become volatile with colonial significance.”7 Like the trade canoes, maps of the United States recur in Smith’s work throughout her career, though in the Whitney’s retrospective several are concentrated into a single gallery space. Viewed together, five map paintings produced over a twenty-one-year period demonstrate the various ways Smith uses maps to think through Indigenous relationships between land, place, and identity. Her most recent map paintings on view here, Survival Map (fig. 4) and Map to Heaven (2021), rotate the map of the United States ninety degrees, upending one perspective to replace it with another. Much of Smith’s work is about providing an Indigenous perspective on the American experience, from negating stereotypes to reminding viewers that Native Americans are present and active in all fifty states.8 These maps, with their subversive orientations, disrupt the viewer’s customary viewpoint in a manner that is both playful and provocative. In a sense, this is Smith playing the role of the trickster, another Indigenous device that persists across her body of work via the figure of Coyote. In Survival Map, the phrase “NDN humor / Causes people / To survive” blends sentiments of humor with trauma in a nuanced manner that artist Jeffrey Gibson (Cherokee and Choctaw) describes as characteristic of Native American humor.9

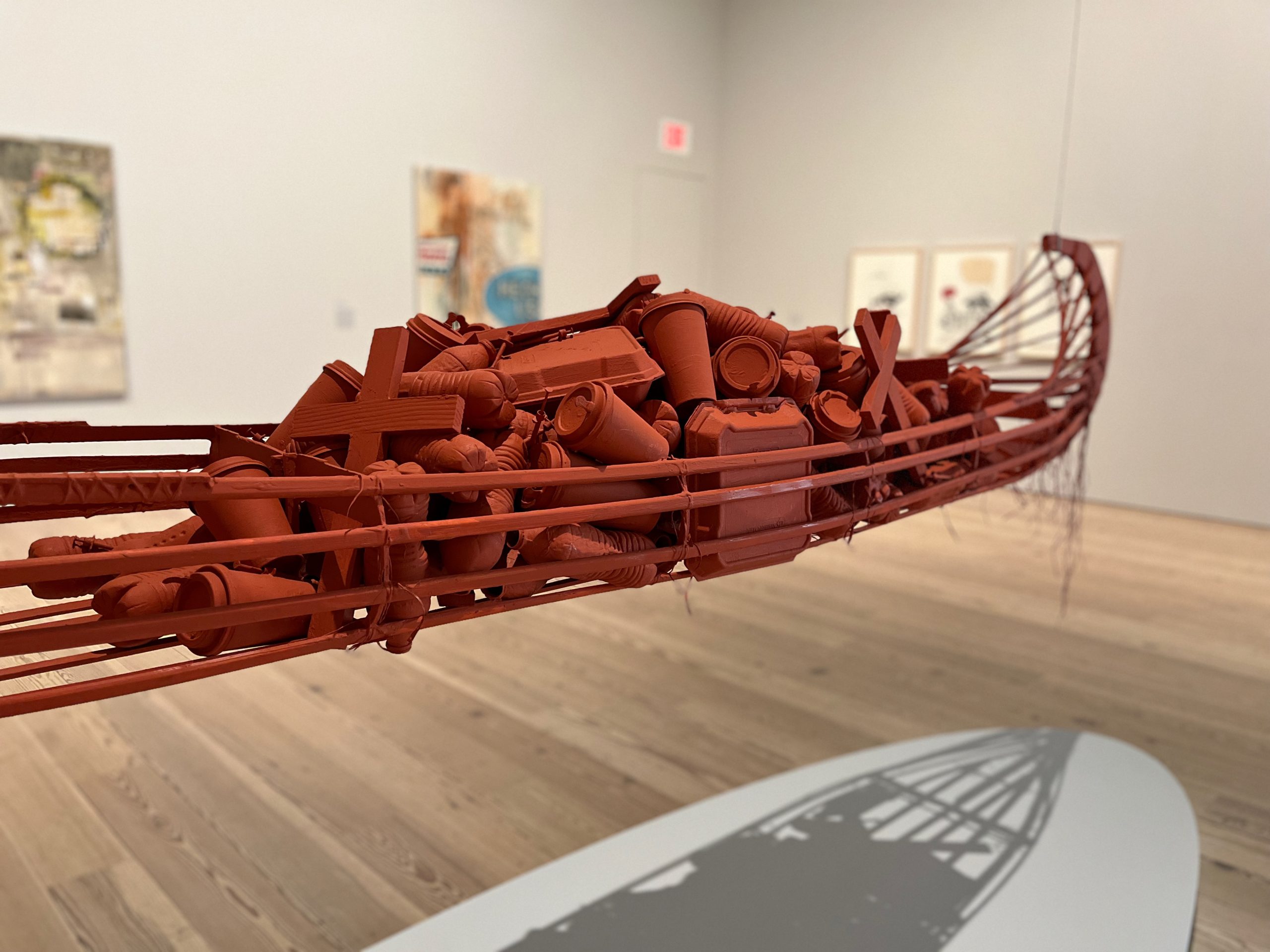

Included in the exhibition are two collaborations between Smith and her son, Neal Ambrose-Smith. Among them is Trade Canoe: Making Medicine (fig. 5), a large, three-dimensional sculpture that broadens the scope of the Trade Canoe series, suspended in the center of the gallery. Visitors can circle the canoe and examine its contents up close: plastic water bottles, disposable coffee cups, take-out containers, hypodermic needles, and wooden crosses—all painted a uniform terracotta red. In this work, the language of realism replaces Smith’s more characteristic expressive brushstrokes, but the message remains consistent. In exchange for the rich natural resources of North America, Indigenous communities have received such destructive interventions as single-use plastics, drug addiction, and a religious philosophy that lacks any sense of equal partnership with the land and its inhabitants. As this expansive retrospective lays bare, Smith’s work speaks fiercely to the repercussions of stolen land as inseparable from an enduring perseverance to maintain connections to that land and its stories. This exhibition invites viewers to share in those connections and to hopefully take more responsibility for the well-being of a place that so many now call home.

Cite this article: Andrea Vázquez de Arthur, review of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, Whitney Museum of American Art, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18197.

Notes

- Laura Phipps, “‘My Roots Extend’: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and the Landscape of Memory,” in Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, ed. Laura Phipps (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2023), 22–31. ↵

- “Jaune Quick-to-See Smith to Curate Exhibition of Contemporary Art by Native Americans at the National Gallery of Art,” press release, National Gallery of Art, March 6, 2023, https://www.nga.gov/press/exhibitions/exhibitions-2023/5549.html. ↵

- Andrea Carlson, “Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights, 2015,” audio guide: 501, Whitney Museum of American Art, accessed August 7, 2023, https://whitney.org/audio-guides/87?language=english&stop=16302&type=general. ↵

- Juliet Eilperin, “Trump to strip protections from Tongass National Forest, one of the biggest intact temperate rainforests,” Washington Post, October 28, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2020/10/28/trump-tongass-national-forest-alaska. ↵

- Lisa Friedman, “Biden Bans Roads and Logging in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest,” New York Times, January 25, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/25/climate/alaska-tongass-national-forest.html. ↵

- Gail Trembley, “Chief Seattle,” in Phipps, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, 94. ↵

- Richard William Hill, “Struggle for the Surface: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” in Phipps, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, 38–43. ↵

- “Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map,” video, Whitney Museum of American Art, accessed August 7, 2023, https://whitney.org/exhibitions/jaune-quick-to-see-smith. ↵

- Jeffrey Gibson, “Survival Map, 2021,” audio guide: 517, Whitney Museum of American Art, accessed August 7, 2023, https://whitney.org/audio-guides/87?language=english&stop=16302&type=general. ↵

About the Author(s): Andrea Vázquez de Arthur is Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York.