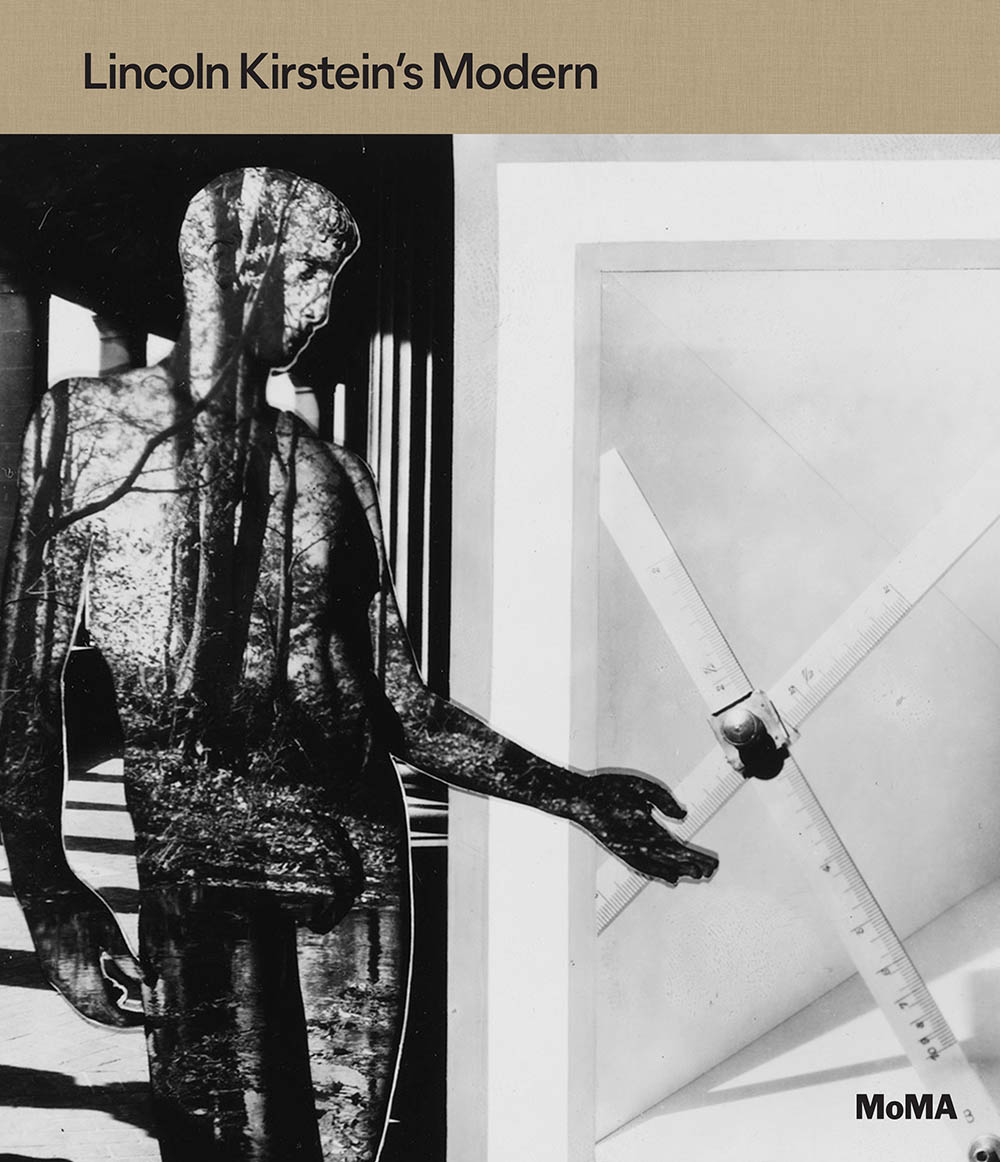

Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern

by Samantha Friedman and Jodi Hauptman

by Samantha Friedman and Jodi Hauptman

with contributions by Lynn Garafola, Michele Greet, Michelle Harvey, Richard Meyer, and Kevin Moore

New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2019. 208 pp.; 170 color illus.; 94 b/w illus.; Hardcover: $55.00 (ISBN: 9781633450820)

Exhibition schedule: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 17–June 15, 2019

The remarkable contribution made by Lincoln Kirstein (1907–1996) to the modern arts in the 1930s and 1940s United States took many forms, but he is still mostly known for enhancing the status of ballet as an American art form. Given that he so successfully spearheaded the American ballet movement, and continued to preside over it into the late 1980s as director of the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and president of the School of American Ballet (SAB), Kirstein’s range of artistic interests is often overlooked. Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, the catalogue for the 2019 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition of the same name, seeks to correct this constrictive categorization by presenting Kirstein as a “key connector and indefatigable catalyst who shaped and supported American artists and institutions in the 1930s and ’40s,” writes Samantha Friedman, cocurator of the exhibition (11). The extent of his influence on the arts has not been sufficiently examined until now; the catalogue therefore fills a significant gap in the critical literature.

Kirstein’s career was impressively varied. In 1932 and 1933 alone, he organized Murals by American Painters and Photographers at MoMA, wrote a regular film column for Arts Weekly, reviewed the photographs of Walker Evans in the Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art and the paintings of Philip Reisman in Hound and Horn, and commissioned a review of books on the Soviet Union. To read his packed diaries from this period, such as a few days in early August 1931, is to move from Walt Disney to Stuart Davis to Erskine Caldwell to Stendhal to Mozart to T. S. Eliot to Ezra Pound to Edith Wharton.1 MoMA was one of Kirstein’s main cultural cornerstones, where he served as a Junior Advisory Committee member, catalogue writer, consultant, and curator. Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern is the first published attempt to honor Kirstein’s involvement with MoMA. Beautifully illustrated with works of art that Kirstein helped procure for the museum, the catalogue also compiles a rich collection of writings that demonstrate Kirstein’s broad-ranging contributions to MoMA.

The catalogue is comprised of an introductory essay, four subject essays by contributing writers—each coupled with a related selection from Kirstein’s own writings—a final excerpt by Kirstein, and a chronology of his life from the museum’s founding in 1929 into the late 1940s. Lynn Garafola examines Kirstein’s contribution to American ballet; Kevin Moore examines Kirstein’s impact on the photographic community at MoMA; and Richard Meyer uncovers how Kirstein’s habit for nonbinary “triangulated relationships” invigorated both his private life and professional projects (100). Finally, Michele Greet relates Kirstein’s firsthand role in expanding MoMA’s collection of Latin American art. Michelle Harvey’s detailed chronology concludes the catalogue. Featuring telling quotations by Kirstein that reveal both the range and character of his dealings with the museum, the chronology is packed with alluring details that go a long way toward clarifying Kirstein’s relationship with MoMA—including the revelation that he often returned remunerations he received for his museum work, and that he proposed various exhibitions over the years that never came to fruition.

Friedman’s introduction provides an excellent characterization of the great breadth of Kirstein’s interests, painting a portrait of a “busy polymath,” with vast and interconnected social and professional networks (11). His interests revolved around supporting the national character of the American arts, including ballet, film, painting, and photography. Kirstein threw his support behind a series of artists and projects, especially when they contributed to “a purely American art,” as he put it.2 In particular, Kirstein championed an “alternative strain of modernism,” Friedman clarifies, one that prioritized realist figuration over abstraction and was rooted in interdisciplinary exploration (14). Importantly, Friedman characterizes Kirstein’s relationship to MoMA as conflicted, stressing that despite his “intimate involvement with MoMA over two decades,” his roles were largely off record, and he repeatedly “refus[ed] additional affiliation” (14). While MoMA was an anchor for Kirstein, it was never a home. Still, he recognized the critical place MoMA held in the development of modern arts in the United States, and he sought to use his substantial influence there to support artists and push for an interdisciplinary version of American modernism. As he announced in “The Future of the Museum of Modern Art” in 1939 (which I note as a somewhat curious omission from Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern), “[MoMA] must directly participate in evolving the art of its epoch,” for it “could serve, ideally speaking, as a highly selective agency for ideal and disinterested patronage.”3 MoMA never quite lived up to his exalted ideals.

Lynn Garafola’s “Lincoln Kirstein: Man of the People” focuses on Kirstein’s central role in developing American ballet. Kirstein persuaded Russian choreographer George Balanchine to immigrate to the United States in 1933. They cofounded the SAB in 1934, and their joint efforts eventually led to the NYCB. One of Garafola’s central arguments about Kirstein’s impact on ballet in the United States is that he challenged Balanchine’s “female-centered” vision of ballet, instead embracing Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev’s “gender revolution—which elevated male dancers to star status” (35, 31).

Of all the essays in the catalogue, Garafola’s considers most openly and inquisitively Kirstein’s understanding of racial dynamics. She argues that Kirstein believed “ballet could be not only a queer space, but also a racially inclusive one,” and she quotes him recognizing “the terrific burden of racism” in the 1960s (32, 33). Garafola details his support of African American dancers, including Betty Nichols, and choreographers, including Talley Beatty, and discusses the impact of the rising Civil Rights Movement on the ballet community in New York. She insists that “the common man—black and white” was central to Kirstein’s understanding of American history (33). Yet she also notes the inconsistences of Kirstein’s patronage of Black artists, as well as the problematic practice of blackface in the 1940s. She concludes her essay with a provocative musing about the missed opportunity of gender and racial diversity in the NYCB due to “Kirstein’s willingness to subordinate his vision to Balanchine’s” (35).

Garafola also references Kirstein’s donation to MoMA of The Hampton Album— a collection of photographs taken between 1899 and 1900 by white photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston that document the Hampton Institute in Virginia, primarily a vocational school founded post–Civil War for newly freed African Americans. The trustees of the school commissioned Johnston to take the photographs, a selection of which were included in The American Negro Exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900, where they won much praise.4 Garafola notes Kirstein’s gift of the album at the end of a paragraph listing projects “that engaged his longstanding concern with social justice” (35). While Kirstein’s discovery of the album and subsequent donation of it to MoMA may speak to his support of civil rights, even a cursory glance at the disquieting photographs that comprise the book prompts further questioning of the complexities of such support. A close reading of Kirstein’s foreword to MoMA’s 1966 exhibition catalogue of The Hampton Album, peppered not only with patronizing racial stereotypes typical of the period but also with language that distributes rather than interrogates racial hierarchy, further calls for deeper interrogation. Garafola’s tempered address of Kirstein’s part in perpetuating the inequitable racial dynamics of the 1930s and 1940s United States awakens this reader’s desire for a more critical analysis of Kirstein’s attitude toward race relations, including his potential assimilationist tendencies.

Finally, Garafola’s characterization of Kirstein’s “leftward drift” would have benefitted from a more specific consideration of Kirstein’s thoughts about the political climate in the 1930s (29). Many artists on the left elided aesthetics and politics in their art following both the stock market crash of 1929 and the rising threat of fascism at home and abroad. Kirstein’s support of them was not about their politics per se, even though their work was often political; it was about stewarding their artistic visions. In this way, Garafola generalizes Kirstein’s leftist leanings.5

Kevin Moore’s “Emulsion Society: Lincoln Kirstein and Photography” provides a superb introduction to Kirstein the “polymath impresario,” offering an expansive vision of his multifarious interests (63). As Moore eloquently articulates, Kirstein “invested in talent by building entire arenas for it” (63). Moore characterizes the socialite Muriel Draper as a “major social and emotional locus for the young Kirstein,” and he smartly positions her New York City salon as a kind of organizational locus for his own essay (65). Taking a cue from Kirstein, Moore channels his own great gift for gossip. To read his essay is to be privy to inside information and intimate details about Kirstein’s social life. Moore’s essay is strongest when he charts Kirstein’s overlapping lines of friendship as they relate to his photographic projects.

Moore’s essay is less strong when assessing the worth of the photographic projects themselves. For instance, Moore refers to MoMA’s Murals by American Painters and Photographers (1932) as “an early career setback” for Kirstein, surely an oversimplified assessment of an exhibition that precociously predated the New Deal mural movement (65). As the first exhibition devoted to murals in the United States, the show played a significant role in the development of muralism as a prevalent New Deal visual form. The biggest weakness of Moore’s essay, though, is its lack of attention to moving pictures, which were absolutely critical to Kirstein’s thinking about photography. He held a sustained and serious interest in film, particularly Soviet film, throughout the 1930s. In 1932, MoMA director Alfred Barr convinced Kirstein to lead MoMA’s film initiatives. While this plan eventually changed course, Kirstein became an outspoken proponent of integrating film into MoMA’s program. While the Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern exhibition was accompanied by the film series Lincoln Kirstein and Film Culture, the catalogue essays themselves are misleadingly silent on Kirstein’s advocacy for film as a fundamental category of modern art.

Richard Meyer’s “Threesomes: Lincoln Kirstein’s Queer Arithmetic” offers a focused examination of Kirstein’s proclivity for threesomes and convincingly demonstrates how “multiple forms of intimacy coexisted in close proximity” in Kirstein’s life (101). Kirstein held a number of sexual relationships with men, often but not always short-lived, all the while maintaining a “loving if complex marriage” to Fidelma Cadmus for fifty years (99). Meyer asserts that Kirstein’s queerness (“queer” being a word of self-identification Kirstein used) “neither defined nor delimited Kirstein’s aesthetic interests,” but rather invigorated them (100).

Meyer cleverly begins his essay with a formal analysis (surprisingly, the catalogue’s first) of a montage portrait of Kirstein by his friend Pavel Tchelitchew. Meyer presents the portrait, featuring a central image of Kirstein flanked by two additional images of him, as symbolic and representational, signifying both Kirstein’s “multidimensional” persona and his fondness for threesomes. While the biographical information Meyer presents is nothing new, by framing Kirstein’s penchant for “triplicity” that departed “from convention—and from normative binary relations, both heterosexual and homosexual,” he unveils a refreshing nonbinary approach to analyzing Kirstein’s life as well as those of his artistic friends and intimate paramours (101,100).

Meyer carries his central argument—that a series of threesomes were central to Kirstein’s life and career—over five different sections, each centered around a wonderful close reading of an image, all of which call attention to triangulated relationships. In the essay’s final section entitled “The Studio,” for instance, Meyer analyzes a photograph by George Platt Lynes featuring Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and George Tooker, each in their own zone within the photograph and in the space of the apartment they share, “separate and yet simultaneous” (105). Cadmus and French were romantically involved at the time, while Cadmus was also pursuing a new love affair with Tooker. In Meyer’s reading of the photograph, “the interior space of artistic production becomes an architecture of erotic attachment” (105). Attention to how Kirstein’s penchant for threesomes affected developments at MoMA would have been an interesting addition to Meyer’s essay.

Michele Greet’s “Looking South: Lincoln Kirstein and Latin American Art” presents a formidable assessment of Kirstein’s impact on MoMA’s Latin American acquisitions and exhibitions in the 1940s. Of all the essays in the catalogue, hers is the most groundbreaking, offering an inclusive account of Kirstein’s role mediating the closely imbricated lines of connection between MoMA and the US government. Greet is the sole essayist of the catalogue to develop her arguments alongside a strong political framework.

Greet offers a corrective to the literature that has typically dismissed Kirstein’s art purchases during his trips to Latin America as “unduly driven by expediency” (145). She presents instead a full contextual picture of the range of circumstances contributing to his purchases. His own penchant for figurative art, she argues, alongside the US government’s embrace of Pan-Americanism “as a political and economic strategy” during the Second World War, led Kirstein to avoid much of the formalist abstraction being produced in the Americas, instead choosing “works that perpetuated a depoliticized, didactic version of American indigenism” (147). He sought local, homegrown South American art, as unbeholden to European trends or training as possible, an approach in search of authenticity whose downside was “reinforc[ing] the notion that art south of the border was naïve and disconnected from North American and European modernist networks” (153). Greet’s important assessment serves as a comprehensive account of Kirstein’s impact on MoMA’s Latin American holdings. Worth mentioning would have been his committed and insightful support of the Mexican muralists, particularly David Alvaro Siqueiros, of whose work Kirstein was perhaps the most perceptive North American reviewer.6

Kirstein would appreciate how wonderfully the essayists highlighted the interpenetration between the private and public worlds so crucial to his life. Yet, I imagine he would have been disappointed that his own professional writings—including the five excerpts included in the catalogue—were not analyzed as closely as his personal diary entries and letters. Instead, the essays penned by Kirstein function more as ancillary appendices. “The State of Modern Painting” (1948), for instance, which fittingly concludes the catalogue, offers an elucidating and quite touching renunciation of Abstract Expressionism that would have been useful to explore in the context of Kirstein’s own distancing from MoMA. He never strayed from his preference for realist figuration, which took him far out of step with the rise of the dominant Abstract Expressionist paradigm by the late 1940s. “Would it not be more interesting,” he wrote, “and less wasteful if pictures were constructed in awe of time, responsible to the lively past, [and] responsible to the awful present . . . ?” (180). Kirstein’s understanding of Abstract Expressionist art as an experimental escape from the “awful present” demonstrates his belief that art ought to engage the social and political realities of its time. Along these lines, a drawback to Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern is an overall lack of attention to concurrent social and political circumstances. MoMA first opened its doors on November 7, 1929, a mere ten days after the stock market crash. The debilitating social effects of this unparalleled economic disaster transpired alongside MoMA’s early development, giving tenor to the important role Kirstein played moderating relations between artists and the institution.

Overall, the catalogue is a formidable contribution to the literature on Kirstein and American modernism. More attention to the social and political conditions of the periods under discussion, and their related art movements, would have offered a more fully developed picture of the arts at MoMA and Kirstein’s involvement in them.

Cite this article: Clara Barnhart, review of Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, by Samantha Friedman and Jodi Hauptman, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10757.

PDF: Barnhart, review of Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern

Notes

- Kirstein, Lincoln, 1907-Papers, (S) *MGZMD 123, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. ↵

- Lincoln Kirstein, Blast at Ballet: A Corrective for the American Audience (New York: Lincoln Kirstein, 1938), 45, as printed in Michelle Harvey, “Chronology,” in Samantha Friedman and Jodi Hauptman, eds., Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern, exh. cat. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2019, 186. ↵

- Lincoln Kirstein, “The Future of the Museum of Modern Art,” Direction 2, no. 3 (May/June 1939): 36, 37. ↵

- The Hampton Album: 44 Photographs by Frances B. Johnston from an Album of Hampton Institute with an Introduction and a Note on the Photographer by Lincoln Kirstein, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art in association with Doubleday, 1966). On Johnston’s photographs of the Hampton Institute, see Judith Fryer Davidov, “Containment and Excess: Representing African Americans,” in Women’s Camera Work: Self/Body/Other in American Visual Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1988), 157–214. ↵

- Garafola incorrectly refers to Shahn as a Communist Party (CP) member. Among a group of politically diverse figures who constituted the US left, Shahn was an ardent New Dealer and progressive liberal who did not share the hardline radical politics of CP members. ↵

- See Lincoln Kirstein, “Siqueiros in Chillan,” Andean Quarterly, Winter 1944, 12–16; and Lincoln Kirstein, “Siqueiros: Painter and Revolutionary,” Magazine of Art 37, no. 1 (January 1944): 22–27, 34. ↵

About the Author(s): Clara Barnhart is an Independent Scholar