“Little of Artistic Merit?”: The Art of the American South

Guest Editor

Contributors

Rachel Stephens, “‘Whatever is un-Virginian is Wrong!’: The Loyal Slave Trope in Civil War Richmond and the Origins of the Lost Cause”

Sarah Beetham, “Confederate Monuments: Southern Heritage or Southern Art?”

Wendy Castenell, “The Architects of Reconstruction: Alcès Family Portraits as Emblems of Afro-Creole Leadership”

Elyse Gerstenecker, “Women’s Work: A Confluence of Education, Design, and Craft”

Ali Printz, “The Modernist Appalachian Aesthetic: The Art of Patty Willis”

Johnna Henry, “The 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders’ Mugshots: A Visual Intervention”

Melissa Mednicov, “Questions of Texas: Avant-Garde and Outlier”

Peter Hah-Chih Wang, “Roaming in the South: Devin Lunsford’s Photographs from the Roadside”

Aleesa Alexander, “Magic City Modern: A Short History of the Birmingham-Bessemer School”

Rachel Kirby, “Unenslaved through Art: Rice Culture Paintings by Jonathan Green”

Since moving to central Alabama in 2015, my knowledge of the field of American art has been fundamentally challenged and reshaped to become more inclusive and more geographically expansive. Like many, my training in American art was a study of urban, mostly Northern centers; at the very least, it never explicitly attended to the arts of the American South as a distinctive regional tradition.1 In order to teach my regional student body (90 percent from Alabama; 57 percent non-white)2 and promote histories to which students feel connected, I have become invested in uncovering the art and architecture in my own backyard. In the summer of 2017, I developed a special topics course on the visual arts of the American South—architecture, material culture, decorative arts, painting, and sculpture—from the colonial settlement to contemporary time. The course explored the interrelationships between history, material and visual culture, architecture, foodways, music, and literature in the formation of regional Southern identities. It addressed topics including the plantation architecture of big houses and back buildings, the narratives of former slaves, the high arts (sculpture and painting) and the vernacular—folk art, basketry, furniture, quilting, WPA photography, and Southern pottery. We adopted a special focus on Alabama, digging into the difficult histories and rich artistic legacies of the state. In constructing the syllabus, I found myself stymied by a dearth of art-historical scholarship on the region, especially articles that might present short case studies or that were written for an undergraduate audience. I am sure that my experiences are not unique to those who seek to unmask regional narratives in their teaching to connect with a local student body. In my case, the writings of John Michael Vlach, Dell Upton, and Maurie McInnis were necessarily supplemented by primary sources, articles, and excerpts from exhibition catalogues.3 Teaching that course forced me to reckon with both the limitations of my own training as an Americanist, and to consider more generally the confines of our discipline. I also became more familiar with the city that I live in: Montgomery, Alabama.

Learning about the South in My Own Backyard

As an outsider—someone not from the South—I am continually confounded by the regional idiosyncrasies. Alabama, like much of the region, is a place of contradictions. The city seal of the state capital, Montgomery, is “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement, Cradle of the Confederacy”; these seemingly incongruous historical moments define the broader regional divisions of the South. The cultural landscape of the city illustrates its opposing histories. Indeed, these two poles are epitomized by dueling tourism sites: the progressive National Memorial for Peace and Justice (fig. 1), alternately known as the National Lynching Memorial, erected by the Equal Justice Initiative in 2018, and the First White House of the Confederacy (fig. 2), which is maintained by the White House Association (WHA) of Alabama (founded in 1900), heroicizes Jefferson Davis, and upholds the Lost Cause ideology.4 Coined in 1866, the Lost Cause is a form of historical revisionism and signifies a pervasive belief system that glorifies the antebellum South and mythologizes Confederate values.5 Followers of the Lost Cause forward the especially pernicious idea that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights and not slavery; it is an assertion that dangerously undermines the links between slavery and white supremacy, contemporary racism, and neo-confederacy.6 In 2007, vandals made those links explicitly clear when they painted the faces and hands of Confederate soldier statues black on the Alabama Confederate Memorial Monument (fig. 3).7 The 88-foot-tall monument (fig. 4) sits to the north of the State Capitol Building and was erected in 1886 to commemorate the state’s 122,000 Confederate veterans.8 A few blocks away, the Civil Rights Memorial (fig. 5), created by Maya Lin (b. 1959) and erected by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 1989, records important dates in the struggle for civil rights. The American Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement are, of course, themselves deeply intertwined—the roots of one fomenting the struggles of the other—and Montgomery occupies a central position within both histories.

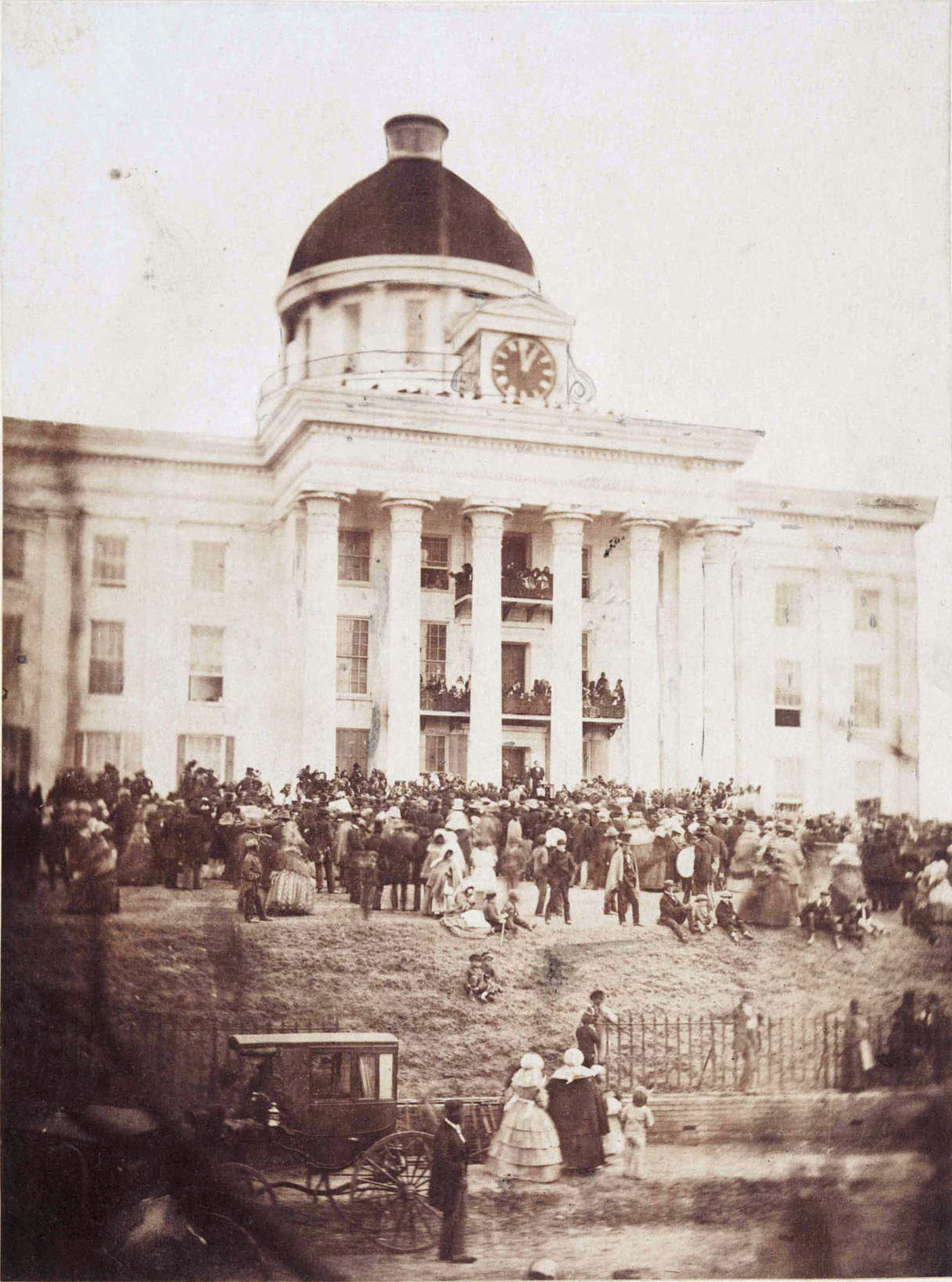

The Civil War (1861–65) began on February 4, 1861, when Jefferson Davis announced the formation of the Confederate States of America (CSA) from the second-floor balcony of the Alabama State Capitol building. Davis was inaugurated as CSA president two weeks later on the capitol building steps (fig. 6). Montgomery was the first capital of the Confederacy before it moved to Richmond, Virginia, in early March. While the state saw its only serious wartime action in Mobile, it was a central economic engine for the Confederacy. Indeed, Alabama was built on “King Cotton” and the associated wealth and history is tied to the enslavement of African Americans, whose bodies sustained the plantation economy through forced labor.9 The continuation of the slave economy was the central platform of the CSA and, following the Union army triumph and the failures of Radical Reconstruction, the white majority sought to maintain racialized systems of inequality, albeit in new guises. Newly enfranchised African Americans were subjected to Jim Crow policies—including strict racial segregation—and became the targets of new forms of systematized violence, including lynching, to incite terror and maintain the hegemony of white supremacy.10

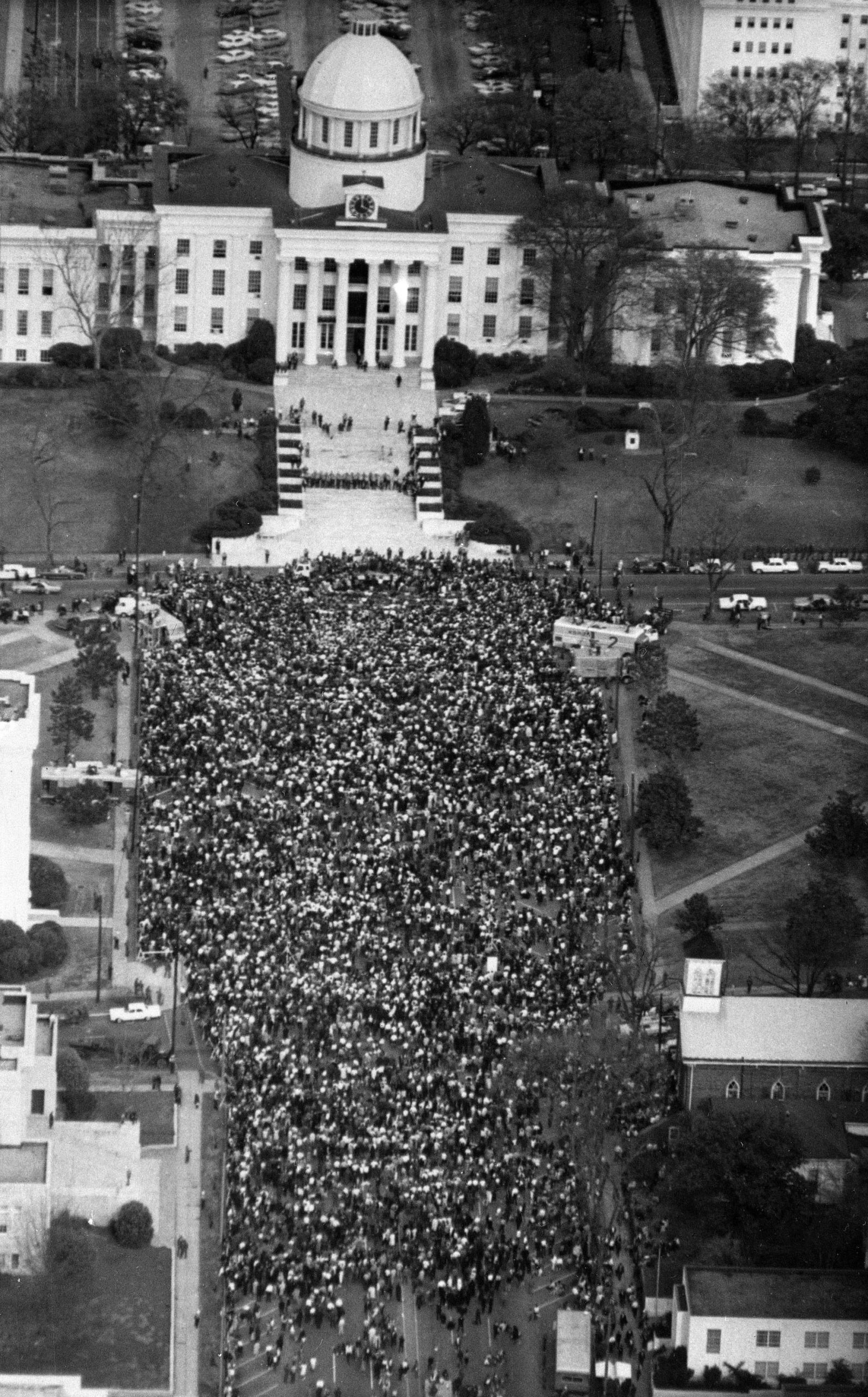

In the mid-twentieth century, Montgomery was home to the Civil Rights movement, owing in part to the position of Martin Luther King, Jr. as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Church from May 1954 through November 1959. During that time, activist Rosa Parks launched the yearlong Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was a non-violent protest to end segregated seating on city public transportation. In February of 1960, thirty-five students from Alabama State College (which was founded by nine freed slaves in 1867 as the first state-sponsored Historically Black College or University in the nation) organized a sit-in at the segregated County Courthouse lunch counter. The following year, Freedom Riders testing desegregation on interstate buses bound for Jackson, Mississippi, arrived in Montgomery. There they were met by an angry white mob—prompting United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy to send federal marshals at King’s request. Four years later, in 1965, King led the five-day, fifty-four-mile march from Selma to Montgomery advocating for voting rights that ended at the steps of the State Capitol Building (fig. 7). There, a crowd of twenty-five thousand onlookers heard King’s “Our God is Marching On!” speech, where he said:

We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. . . . That will be the day of man as man . . . however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.11

From our current historical position, that arc may seem long indeed. Yet, “change is a’comin’”12—even here. In 2019, Montgomery—which, like many Southern cities, is majority black13—elected its first African American mayor, Steven Reed.14

The transformation of the South in the twenty-first century is typified by similar historical inequities and cultural contradictions and is defined by continued social challenges and also broadening opportunities. Resources such as the Invisible Histories Project, which archives Alabama LGBTQ history, and the Southern Oral History Project, which has been collecting interviews since 1973, alongside initiatives such as Beyond and Behind the Big House and the Slave Dwelling Project, expand regional narratives, confront imagined stereotypes about the South, and strengthen individual communities through projects that tap collective memory and preserve untold histories. Contemporary artists are also taking on the weight of Southern history, drawing inspiration from its pasts to create innovative works that envision new futures. From the textile-based work of Sonya Clark and the tapestries of Noel Anderson, to the mapping projects of Celestia Morgan and the sculpture of Stephen Hayes, such artists are reaching new audiences via art galleries and museums. In so doing, they are also broadening the conversation about the South and its national legacies. These projects and individuals aim to redress Southern archetypes and redefine the South not as static and monolithic, but instead as a space that is fluid, multicultural, and complex. Living in the South, surrounded by such rich histories and innovative forward-looking initiatives, I learn something new each day about what it means to be an Americanist.

A Problem of Boundaries: Defining the South

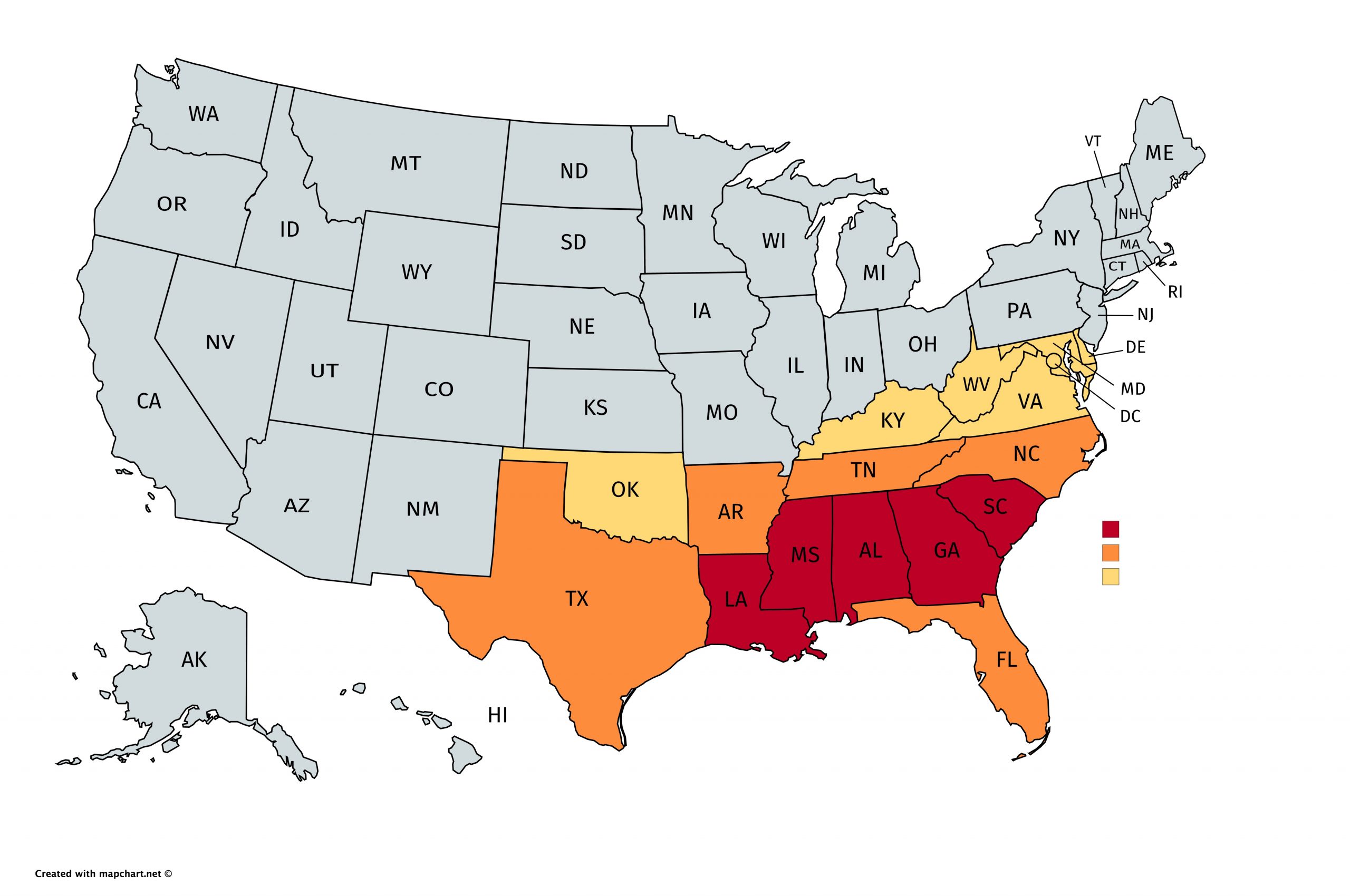

The first problem in writing an art history of the American South is the challenge of defining the regional boundaries; just what is the South? Depending on what you consult (fig. 8), the South contains six states (the Old South), eleven states (Dixie), fifteen states (slave states before 1860), or sixteen states (the US Census).15 It may seem obvious that Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia are in the South, but what about Texas, Florida, Arkansas, or Maryland? The South is comprised of various regions, including greater Appalachia, the Deep South, Acadiana, the Tidewater, the Low Country, and the Gulf South, and each one of these regions has its own distinctive community, identity, and history.16 The South is frequently framed by the history of the American Civil War and is associated in the national cultural imagination with right-wing, neoliberal, and conservative Christian values; stereotypes of soul food eating, blues-playing African Americans, gun-totin’ rednecks, and bible thumpin’ hillbillies abound.17 Yet, the South is also deeply multicultural, and there is a modern, or new, New South on the rise.18 Metropolitan centers such as Charleston, South Carolina; Chattanooga, Tennessee; and Greenville, South Carolina19 are experiencing rapid population growth and drawing younger residents between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four; these cities have begun to embrace multiculturalism, urban development, and more progressive anti-racist, decolonial values, leading to what some call a “cosmopolitan New South.”20

Grappling with the slipperiness of the South seems especially important today. The expanding social and political divides in this country are also geographic registers of ideological value systems, often based around shared identities and experiences of place. Consequently, regional difference becomes marked by an “us” versus “them” mentality. As Joel Garreau argued in 1981, such distinctions based upon regional identity define nine stateless nations that compose the United States.21 In American Nations: A History of Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, Colin Woodard expanded upon this premise and linked these regional divisions to their unique histories and founding mythologies.22 Indeed, in my own experiences, one ideological difference between the South and the North is made evident by considering the meanings tied to two colonial founding narratives. New Englanders take pride in the story of the Pilgrims who fled the old world for the New World in search of religious freedom; Southerners revel in the narrative of economic independence embedded in the tales of second sons, who found prosperity by shipping to the Southern colonies. One ideal aspires to collectivity and tolerance; the other to individual fortitude. Of course, both are pure fiction and part of a white imaginary. Yet, these deeply rooted beliefs speak to the power of narrative history to unite or enforce divisions through erasure. Therefore, as Americanists, reckoning with the South might also help us to understand its diverse regional histories and reflect upon broader national contemporary discourses, both from within and without.

Why Have There Been No Great Southern Artists?

As with Linda Nochlin’s leading 1971 question regarding the absence of women from the art-historical canon,23 I seek here to provocatively raise a question about the exclusion of Southern art from most studies of American art, instead of asserting that there are not great Southern artists. Instead, one might ask how the constructs of the discipline itself have allowed the South to be overlooked or, perhaps, intentionally excluded from the textbooks. In the case of canonized early American artists, such as Washington Allston (1779–1843)—born in Georgetown, South Carolina—or Thomas Sully (1783–1872)— who grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, and lived in Richmond, Virginia—their Southern origins are often ignored in favor of their national import or Northern connections.24 In the reverse, numerous twentieth-century Southern artists are categorized as self-taught, a designation that naturally positions them outside of the canon, as Miranda Lash points out in her essay, “What Do We Envision When We Talk about the South?”:

In the art world, the South continues to be regarded both internally and externally as a zone peripheral to the intellectual and commercial traffic of New York and Los Angeles. . . . On occasions where the South as a region does enter contemporary art discourse, it often falls under the auspices that it is a natural hotbed of creativity for artists who have been classified as “self-taught,” “visionary,” or otherwise “naïve.”25

Such characterizations stigmatize these artists and their work as somehow lesser than their academically trained counterparts. While this line of questioning comes down to issues of canon formation—and I do not intend to write a historiography of American art here—I do want to consider how and where we geographically center our discipline and what gets left out.26 Why is the South almost always on the periphery?

Undoubtedly, certain conditions affected the early development of the arts in the South. In contrast to the North, the South suffered from a lack of institutional bases for formal art training.27 The region is, however, especially rich in craft traditions, with artisans working in methods and materials that have been historically undervalued by art historians. Craft traditions, such as basketry, ironwork, ceramics production, furniture making, and quilting, have only just begun to gain widespread acceptance within the academic hierarchies of art history.28 In addition, during Reconstruction and well into the mid-twentieth century, there was entrenched nativism within the American South, which sought to privilege white, regional traditions and histories over a national or Northern shared heritage.29 This resulted in Southerners writing about the South for Southern audiences. As Ronald L. Hurst says in his recent state of the field on Southern furniture studies, “these publications were generated by Southern scholars and institutions. There was still little interest in the subject beyond the region.”30 Such insularity is relevant even today; studies of Southern material still tend to be internally generated and consumed by Southern audiences.

By the 1930s, a version of American folk art was being exported from regions in the South and marketed to mostly middle-class, white audiences.31 This coincided with the WPA historical surveys to document colonial American architecture, painting, and material culture and aligned with the drive to create a shared, usable past, as epitomized by Colonial Williamsburg.32 These various projects presented a whitewashed colonial narrative of prosperity, which often failed to include people of color. Such movements had the dual effect of making the South more insular and less open to outsiders and also excluding people of color from a Southern canon. As John Michael Vlach famously wrote of Southern African American folklife in his landmark publication, By the Work of Their Hands:

In the History of the United States the stories of the politically and economically disenfranchised are rarely told, and when they are, it is usually from the perspective of those who hold power. . . a people bereft of a history—without a past—has no reliable source for its identity.33

As Vlach here makes clear, the majority of the Southern art histories that were written in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries focused almost entirely on white makers and operated to support systems of white supremacy and rob Southern African Americans of a historical legacy, shared culture, or communal identity. Contemporary craft practitioners, including sweetgrass basket maker Mary Jackson (b. 1945) and the Gee’s Bend Quilting Collective, are challenging that premise by carrying on regional, generationally inherited practices.

One anecdote is indicative of the ways in which Southern art has been marginalized more broadly within the field of American art. In 1949, The Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Joseph Downs articulated a widespread aversion to Southern art, remarking that “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.”34 As Maurie McInnis explains in her article advocating expanding the study of the eighteenth century into the American South, Downs’s dismissive characterization of Southern art as forgettable and without merit, and the wider exclusion of Southern art from histories of the discipline, can be traced to a number of factors. These include the focus of the first histories of American art written by William Dunlap in 1834, which favored New York; the development of vernacular and regional artistic traditions over institutionalized modes of instruction and artistic practice; and “the region’s commitment to the institution of slavery,”35 which stigmatized Southern art at the very least as “thorny,” if not backward, aberrant, or downright dangerous. Taken together, these varying historical circumstances had the consequence of further establishing the South as somehow “other” in relation to an American normal.36

Building a Broader, More Inclusive History of American Art

Scholarship on art of the American South has matured since McInnis’s article, alongside increasing recognition that the disciplinary marginalization of Southern art is based upon historical, material, racial, and geographic biases.37 Since 2005, our field has benefited from a growing body of individual studies on Southern artists, public monuments, vernacular art and architecture, and African American arts of the South.38 This renewal has been spurred by insightful scholarly publications, innovative museum exhibitions, robust Southern contemporary art scenes, and conferences focused on regional artistic traditions, legacies, and contemporary practices. Academic and cultural institutions are leading the way in this transformation, including interdisciplinary programs focused on Southern studies and New Southern studies,39 the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Prospect New Orleans, Souls Grown Deep Foundation, South Arts (formerly the Southern Arts Federation), and the Society 1858 Prize for Contemporary Southern Art, as well as publications, such as the Journal of Southern History; the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, published by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture; Burnaway: The Voice of Art in the South; and Southern Cultures, published by the Center for the Study of the American South. My own small contribution to this work includes directing the annual Southern Studies conference.

In order to add to this growing discourse, I organized a double session in 2018 for the annual SECAC conference (formerly the Southeastern College Art Conference) held in Birmingham, Alabama, titled “‘Little of Artistic Merit?’: The Art of the American South.” Its title borrowed from McInnis and Downs, that SECAC double session was intended to provide a platform for scholars to present their research on the arts of the American South. This In the Round extends that platform, bringing such scholarship to Panorama readers.

These ten essays, when read together, illuminate the breadth of the region and its artistic histories. They span eight southern states; treat photographs, paintings, sculpture, and visual and material culture; and cover the Civil War period to contemporary time. Rachel Stephens examines Lost Cause mythology—especially the idea of the loyal slave—as promoted in the works of pro-Confederacy Virginia artists, including William D. Washington in his 1864 painting The Burial of Latané (1864; The Johnson Collection). In contrast, Wendy Castenell examines Afro-Creole patronage in New Orleans during the period of Reconstruction, arguing that through portraiture, newspapers, and poetry this elite community was able to support radical political movements and demand broader rights for African Americans. Perhaps more significant are the ways in which their racial mutability and position within New Orleans society raised questions about the strict binary of race adopted in most of the United States. Sarah Beetham studies the longevity of the Lost Cause ideology and its physical mark on the Southern landscape through the use of Confederate monuments. She introduces contemporary art projects that seek to counteract or invalidate the power of such public icons. Elyse Gerstenecker expands upon the role of Southern women in shaping regional material culture through a study of turn-of-the-century art schools in Abingdon, Virginia; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Asheville, North Carolina. Also considering the influence of women on Southern regional styles, Ali Printz introduces readers to the career of West Virginia artist Patty Willis, whose wide-ranging practice Printz provocatively dubs “Appalachian modernism.” Melissa Mednicov raises historiographic questions about canon formation in her essay, which contrasts the legacies and reputations of two Texas artists, Robert Rauschenberg and Forrest Bess. Turning to photography, Peter Han-Chih Wang examines one portfolio by contemporary Alabama photographer Devin Lunsford, introducing the various canonical photographers whose Southern imagery influenced its production. Johnna Henry studies the format of the mugshot, articulating how Freedom Riders may have staged visual interventions to enact agency over their images. Aleesa Alexander presents an overview of the works of the Bessemer School of artists, a group of twentieth-century black artists working in the greater Birmingham area. Through this analysis, Alexander reveals the ways in which such artists developed a subversive practice that counters dominant political and artistic modes. And Rachel Kirby studies the work of Charleston, South Carolina, artist Jonathan Green and contrasts it with Alice Ravenel Huger Smith’s watercolors of rice production in order to show how Green constructs a language of “unenslavement.” Kirby’s essay argues for a radical reenvisioning of the Southern past and its potential futures through the power of art.

Together, these contributions demonstrate the surprising histories and variety of Southern art and culture. Collectively, the authors question whether there is something uniquely Southern about the arts of the South—situating their artists and areas of study within the region’s ambiguous geographic borders and amorphous histories. This is by no means an exhaustive compilation. Indeed, these essays barely scratch the surface. Instead, it is hoped that these studies will encourage our field to expand the geographic reach of surveys of American art and inspire future art-historical analyses of the visual and material cultures of the region. Such scholarship may prove, once and for all, the artistic merit of the arts of the American South.

Cite this article: Naomi Slipp, “‘Little of Artistic Merit?’: The Art of the American South,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9932.

PDF: Slipp, Little of Artistic Merit?

Editors’ note, June 29, 2020: Post-publication, the author received a critique on this introduction that they would like to address. The critic noted that there was a lack of diversity reflected in footnoted scholarship. In order to redress some of this criticism, the author would like to underscore that many scholars are producing important interdisciplinary scholarship in this field of study. The author has added footnote 37, which briefly outlines some of the important work being done by the many academics and curators working on Southern art and culture.

Notes

- I do not intend to rake my graduate instructors over the coals here. Certainly, courses focused on African American art, material culture, and American architecture did address the art of the South, but it was never presented as a distinctive tradition, or at least not in a way that really sank in for me as something drastically different from Northern developments. ↵

- “Spring 2020 enrollment,” and “Fall 2019 First Time Freshman cohort,” Auburn University at Mongtomery, accessed April 23, 2020, http://www.aum.edu/sites/default/files/202002_SP%2020%20Enrollment%20Data%20Summary_JG_3_31_20.pdf and http://www.aum.edu/sites/default/files/Fall_2019_New_student_report.pdf. ↵

- Readings included Maurie McInnis, Slaves Waiting for Sale (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011); Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach, eds., Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986); Dell Upton, What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument-Building in the Contemporary South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015); John Michael Vlach, By the Work of Their Hands: Studies in Afro-American Folklife (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992); John Michael Vlach, The Planter’s Prospect: Privilege and Slavery in Plantation Paintings (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); E. Bryding Adams, ed., Made in Alabama: A State Legacy, exh. cat. (Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1995); Robert Delehanty, Art in the American South: Works from the Ogden Collection (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996); Jessie J. Poesch, The Art of the Old South: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, and the Products of Craftsmen, 1560–1860 (New York: Harrison House, 1983); Estill Curtis Pennington, Look Away: Reality and Sentiment in Southern Art (Spartanburg, SC: Saraland Press, 1989); and Richard Powell and Jock Reynolds, To Conserve a Legacy: American Art From Historically Black Colleges and Universities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999). ↵

- The Associated Press, “Does First White House of the Confederacy ‘Whitewash’ Evils of Slavery?,” AL.com, accessed April 20, 2020, https://www.al.com/news/2017/05/does_first_white_house_of_the.html. ↵

- The term first appeared in Edward Pollard, The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates (New York: E. B. Treat, 1866). ↵

- Karen L. Cox, “Lost Cause Ideology,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, accessed on May 4, 2020, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1643. ↵

- Desiree Hunter, “Alabama Capitol’s Confederate Monument Vandalized,” Decatur Daily, accessed May 4, 2020, November 15, 2007, http://legacy.decaturdaily.com/decaturdaily/news/071115/cap.shtml. ↵

- Michael W. Panhorst, accessed May 4, 2020, “Confederate Monument on Capitol Hill,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3086. ↵

- According to the US Census, in 1860, there were 435,080 enslaved persons in the state of Alabama. “Population of the United States in 1860,” United States Census Bureau, accessed April 21, 2020, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1864/dec/1860a.html. ↵

- According to the Equal Justice Initiative database, there were 361 reported lynchings in Alabama between 1877 and 1950, including 12 in Montgomery County. Equal Justice Initiative, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” 3rd ed. (Montgomery, AL: Equal Justice Initiative, 2017), 40, accessed online April 23, 2020, https://eji.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/lynching-in-america-3d-ed-080219.pdf. ↵

- “‘Our God is Marching On!,’ March 25, 1965, Montgomery, AL,” Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, accessed April 23, 2020, Stanford University, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/our-god-marching. ↵

- “A Change Is Gonna Come” is a song by American recording artist Sam Cooke. Recorded and released in 1964, it became an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. See David Cantwell, “The Unlikely Story of ‘A Change is Gonna Come,” New Yorker, March 17, 2015, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-unlikely-story-of-a-change-is-gonna-come. ↵

- According to 2018 United States Census data, the city population is around 198,000. Demographically, over 60 percent of the population identifies as black/African American and 37 percent identifies as white/non-Hispanic. “Quick Facts: Montgomery City, Alabama,” United States Census Bureau, accessed April 24, 2020, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/montgomerycityalabama/RHI225218#RHI225218. ↵

- Rick Rojas, “Montgomery, a Cradle of Civil Rights, Elects Its First Black Mayor,” New York Times, October 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/09/us/montgomery-alabama-mayor-steven-reed.html. ↵

- For more on this question, see Christopher Cooper and H. Gibbs Knotts, “South Polls: Rethinking the Boundaries of the South,” Southern Cultures 16, no. 4 (Winter 2010): 72–88. ↵

- For an argument toward including the Southern and Caribbean colonies in American art histories, see Maurie McInnis, “Little of Artistic Merit?: The Problem and Promise of Southern Art History,” American Art 19, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 11–18. For a consideration of how to define the nebulous South and its art, see Trevor Schoonmaker, “Southern Accent: The Sound of Seeing,” in Southern Accents: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art, exh. cat., ed. Miranda Lash and Trevor Schoonmaker (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 54–74. ↵

- Patrick Gerster, “Stereotypes,” in New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, vol. 4, ed. Wilson Charles Reagan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 170–75, accessed April 23, 2020; James C. Cobb, Away Down South: A History of Southern Identity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and James C. Cobb, Redefining Southern Culture: Mind & Identity in the Modern South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999). ↵

- The New South refers to a movement in the post-Civil War South that advocated an economic shift from the agrarian-focused plantation economy to one based upon industry and infrastructure. While it was economically forward looking, it was also deeply entwined with white supremacism. See Rob Dixon, “New South Era,” in Encyclopedia of Alabama, accessed April 23, 2020, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2128. ↵

- Jacki Renegar, “2019: Exactly How Many People Move to the Charleston Region Each Day?” Charleston Regional Development Alliance, accessed April 28, 2020, https://www.crda.org/news/2019-exactly-how-many-people-move-into-the-charleston-region-each-day; Jada Yuan, “Chattanooga Is Changing. But Its Charms Remain,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/20/travel/chattanooga-is-changing-but-its-charms-remain.html; “Greenville named fourth fastest-growing U.S. city,” Greenville News, https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/2017/05/25/greenville-named-fourth-fastest-growing-u-s-city/344009001. ↵

- I am not the first to adopt these terms to describe twenty-first-century shifts in Southern culture and regional identity. For example, Craig Thompson and Kelly Tian explore the connections between New South mythology and contemporary cosmopolitan New South ideologies in “Reconstructing the South: How Commercial Myths Compete for Identity Value through the Ideological Shaping of Popular Memories and Countermemories,” Journal of Consumer Research 34, no. 5 (February 2008): 595–613. Likewise, foodways scholars use the term “New Southern cuisine” to describe the rise of chefs such as Sean Brock and Mashama Bailey. See Erin Byers Murray, “The New Southern Cuisine: Don’t Call It Fusion,” Thrillist, accessed April 28, 2020, https://www.thrillist.com/eat/nation/southern-food-evolving-2019. ↵

- Joel Garreau, The Nine Nations of North America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981). ↵

- Woodard posits that there are eleven distinctive “stateless nations” that comprise the United States. See Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (New York: Penguin Books, 2011). Another popular work of nonfiction that examines Southern historical mythologies and identity formation is Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998). ↵

- Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” in Linda Nochlin, Women, Art and Power and Other Essays (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988), 147–58. This article was first published in the January 1971 issue of ARTnews. ↵

- I am grateful to Rachel Stephens for pointing out the common erasure of Southern origins from biographies of early American artists. ↵

- Miranda Lash, “What Do We Envision When We Talk about the South?,” in Southern Accents, 20. ↵

- For broader considerations of the formation of American art as a discipline, see John Davis, “The End of the American Century: Current Scholarship on the Art of the United States,” Art Bulletin 85, no. 3 (September 2003): 544–80; Barbara Groseclose and Jochen Wierich, eds., Internationalizing the History of American Art (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009). ↵

- Art academies modeled after French and British institutions were founded in the United States as early as 1802 (American Academy of the Fine Arts, New York City); however, no formalized, dedicated institution for studying the fine arts existed in the colonial or antebellum South. ↵

- Southern craft history, folk traditions, and material culture studies have had broader acceptance in fields adjacent to art history, such as American studies, literature, Southern studies, history, historic preservation, anthropology, and sociology. For recent interdisciplinary studies of the South, see for, example, Jon Smith and Deborah Cohn, eds., Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Brian Ward, ed., The American South and the Atlantic World (Tallahassee: University Press of Florida, 2013). ↵

- For an excellent timeline on the development of Southern art institutions, see Andrew Hibbard, “Chronology of Southern Art and Scholarship,” in Southern Accents, 213–19. For more on the whitening of regional folk traditions and Southern art, consider early twentieth-century studies, such as Mary de Berniere Graves, A Study of American Art and Southern Artists of Note (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1929); A. H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery (Strasbourg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929); Allen Eaton, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1937); Alston Deas, Early Ironwork of Charleston (Columbia, SC: Bostick & Thornley, 1941), which largely present a whitewashed view of Southern folk traditions. ↵

- Ronald L. Hurst, “Southern Furniture Studies: Where We’ve Been, Where We’re Going,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 36 (2015), accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.mesdajournal.org/2015/southern-furniture-studies-weve-been-were. ↵

- As Jane S. Becker points out, “In the 1930s . . . a majority of the ‘folk’ handicrafts purchased in this decade were made by Native Americans or by people residing in the mountains of the Appalachian South. . . . As ideological constructs, definitions were shaped by notions of gender, race, and ethnicity and by social and economic relations in specific historical contexts. Thus we must consider exactly who defined the folk and tradition.” Jane S. Becker, Appalachia and the Construction of an American Folk, 1930–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 13. The 1930s also saw the rise of the Southern Renaissance literary movement and “old southern studies” in academia. Finally, one could also consider the discovery and canonization of vernacular African American art in this same moment; see Jennifer Jane Marshall, “Nashville, New York, Paris, and Nashville: William Edmondson, Mobilized and Unmoved,” American Art 31, no. 2 (Summer 2017): 69–76. ↵

- On the search for a usable past as a modernist impulse, see Terry Smith, Making the Modern: Industry, Art, and Design in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993). ↵

- Vlach, By the Work of Their Hands, xvii, 2. ↵

- McInnis, “Little of Artistic Merit?” 11. ↵

- McInnis, “Little of Artistic Merit?” 12; and William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, vols. 1 and 2 (New York: Scott, 1834). ↵

- Orville Vernon Burton, “The South as ‘Other,’ the Southerner as ‘Stranger,’” Journal of Southern History, 79, no. 1 (February 2013): 7–50. ↵

- Some of those who have previously researched and written histories of Southern art and culture (and who continue to do so) include Riché Richardson, who also edits the series New Southern Studies published by University of Georgia Press, and whose publications include Black Masculinity and the U.S. South: From Uncle Tom to Gangsta (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007), “Kara Walker’s Old South and New Terrors,” NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art 25 (2009): 48–59, and “Artistically Re-Creating and Re-Imagining Mammy, Rhett and Scarlett,” in New Approaches to Gone with the Wind, ed. Andy Crank (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015); Richard J. Powell, whose extensive publications include African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond (Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2012), and numerous studies and articles on artists of the Harlem Renaissance, antislavery portraiture, and emancipation and sculpture, among many other topics; Dana E. Byrd, whose digital art history projects and scholarship focus on the arts of the South, including “‘Motive Power’: Punkahs and Performance in the Antebellum South,” Buildings and Landscapes, Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, 23, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 29–51, and “Tracing Transformations: Hilton Head Island’s Journey to Freedom, 1860–1865,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 14, no. 3 (Fall 2015), https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/autumn15/byrd-hilton-head-island-journey-to-freedom-1860-1865; E. Patrick Johnson, whose scholarship focuses on Blackness, queer identity, performance, and the South, and whose books include Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South—An Oral History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), Honeypot: Black Southern Women Who Love Women (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), and Black. Queer. Southern. Women.: An Oral History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Nell Painter, whose academic books include Creating Black Americans: African American History and Its Meanings, 1619 to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) and Southern History Across the Color Line (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Huey Copeland, whose scholarship includes Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), and who guest edited and co-wrote “Perpetual Returns: New World Slavery and the Matter of the Visual” with Krista Thompson, for a special topics issue of Representations 13, no. 1 (2011): 1–15; Krista Thompson, who works on the Caribbean and African diaspora and has published Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), An Eye for the Tropics: Photography, Tourism, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), “A Sidelong Glance: The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States,” Art Journal (Fall 2011): 6–31, and “The Evidence of Things Not Photographed: Slavery and Historical Memory in the British West Indies,” Representations 113 (Winter 2011): 39–71; Jodi Skipper, who co-edited (with Michele Grigsby Coffey) Navigating Souths: Transdisciplinary Explorations of a U.S. Region (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017), and launched the Behind the Big House Project described in “Community Development through Reconciliation Tourism: The Behind the Big House Program in Holly Springs, Mississippi,” Community Development 47, no. 4 (February 2016): 514–29; Daina Ramey Berry, whose books on the histories of slavery include The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation (Boston: Beacon, 2017) and Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe: Gender and Slavery in Antebellum Georgia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007) and who has also co-edited two volumes with Leslie M. Harris, Sexuality & Slavery: Reclaiming Intimate Histories in the Americas (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018) and Slavery and Freedom in Savannah (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014); historian Robert A. Pratt, The Color of Their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond, Virginia, 1954–89 (Richmond: University of Virginia Press, 1992), We Shall Not Be Moved: The Desegregation Of The University Of Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002), and Selma’s Bloody Sunday: Protest, Voting Rights, and the Struggle for Racial Equality (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017); scholars of Southern literature, such as Sherita L. Johnson, Black Women in New South Literature and Culture (London: Routledge, 2010); Deborah Plant, whose publications on Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston include editing Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” (New York: Amistad, 2018) and authoring Every Tub Must Sit on Its Own Bottom: The Philosophy and Politics of Zora Neale Hurston (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1995); those who work on Indigenous histories and lived experiences in the South, such as Fay A. Yarbrough, whose publications include Race and the Cherokee Nation: Sovereignty in the Nineteenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008) and “Power, Perception, and Interracial Sex: Former Slaves Recall a Multiracial South,” Journal of Southern History 71, no. 3 (August 2005), 559–88; Kathryn H. Braund, who publishes extensively on the Creek Indians and William Bartram, including Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993) and co-edited The Old Federal Road in Alabama: An Illustrated Guide (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2019); Angela Pulley Hudson, Real Native Genius: How an Ex-Slave and a White Mormon Became Famous Indians (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015) and Creek Paths and Federal Roads: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves and the Making of the American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); and Christina Snyder, whose books include Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Age of Jackson (Oxford: Oxford University, 2017) and Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), and contributed to The Native South: New Histories and Enduring Legacies (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), co-edited by Greg O’Brien and Tim Garrison; those working on Southern foodways, like Elizabeth Engelhardt, whose books include A Mess of Greens: Southern Gender and Southern Food (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011); culinary historians Jerome Bias, who practices hearth cooking in living history demonstrations, and Michael Twitty, who authored The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South (New York: HarperCollins, 2017); and scholars at the Southern Foodways Alliance, which has published edited volumes including The Larder: Food Studies Methods from the American South (2013), Rafia Zafar’s Recipes for Respect: African American Meals and Meaning (2019), and Angela Jill Cooley’s To Live and Dine in Dixie: The Evolution of Food Culture in the Jim Crow South (2015) through its series with University of Georgia Press; the many curators who work on Southern art and culture, including Jontyle Robinson at The Legacy Museum, Tuskegee University; Valerie Cassel Oliver at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; Pam Wall at the Gibbes Museum of Art; Nandini Makrandi Jestice at the Hunter Museum of American Art; and Bradley Sumrall at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. Finally, there is a deep well of scholarship devoted to the complex histories of migration from the South, including artists associated with the Great Migration and the forced relocation of Indigenous peoples to territories and reservations. ↵

- Such scholarship includes Helen Molesworth, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015); Timothy A. Burgard, Revelations: Art from the African American South, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2017); Carolyn Weekley, Painters and Paintings in the Early American South (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2013); Carol Crown, Sacred and Profane: Voice and Vision in Southern Self-Taught Art (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2007); Angela Mack and Stephen Hoffius, eds., Landscape of Slavery: The Plantation in American Art, exh. cat. (Augusta, GA: Morris Museum of Art, 2008); Rachel Stephens, Selling Andrew Jackson: Ralph E. W. Earl and the Politics of Portraiture (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2018); Leslie Umberger, Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, exh. cat. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018); Cheryl Finley, et al., My Soul has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018); Martin A. Berger, “Fixing Images: Civil Rights Photography and the Struggle Over Representation,” RIHA Journal 10 (October 21, 2010), https://www.riha-journal.org/articles/2010/berger-fixing-images; Reiko Hillyer, “Relics of Reconciliation: The Confederate Museum and Civil War Memory in the New South,” The Public Historian 33, no. 4 (November 2011): 35–62; Elizabeth M. Gushee, “Travels through the Old South: Frances Benjamin Johnston and the Vernacular Architecture of Virginia,” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 27, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 18–23; Daniel J. Vivian, “A Practical Architect: Frank P. Milburn and the Transformation of Architectural Practice in the New South, 1890–1925,” Winterthur Portfolio 40, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 17–46; Karen Kingsley, “New Orleans Architecture: Building Renewal,” The Journal of American History 94, no. 3 (December 2007): 716–25; Matthew Sutton, “Little America: R. E. M., Howard Finster, and the Southern ‘Outsider Art’ Aesthetic,” Studies in Popular Culture 30, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 1–20; Sarah Beetham, “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter,’” Public Art Dialogue 6 (2016): 9–33; Patricia Hills, “Cultural Legacies and the Transformation of the Cubist Collage Aesthetic by Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Other African American Artists,” in Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis, eds., Romare Bearden, American Modernist, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011). ↵

- A movement within the field of Southern studies is pushing for a New Southern studies, one that is decentered, decolonialized, and diverse. See Houston Baker and Dana Nelson, “Preface: Violence, the Body, and ‘The South,’” American Literature 73, no. 2: (2001): 231–44; Scott Romine and Jennifer Rae Greeson, eds., Key Words for Southern Studies (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016); Brian Ward, “Forum: What’s New in Southern Studies—and Why Should We Care?,” Journal of American Studies 48, no. 3 (August 2014): 691–733; Jon Smith, “What the New Southern Studies Does Now,” Journal of American Studies 49, no. 4 (October 2015): 861–70. For more on the academic backlash against the New Southern studies movement, consider the Abbeville Institute (https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org), which the The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) characterizes as similar to the League of the South and linked with neo-Confederate ideology. See Heidi Beirich and Mark Potok, “The Ideologies,” Intelligence Report, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2004/ideologues; Ben Terris, “Scholars Nostalgic for the Old South Study the Virtues of Secession, Quietly,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, December 6, 2009, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Secretive-Scholars-of-the-Old/49337. ↵

About the Author(s): Naomi Slipp is Assistant Professor of Art History at Auburn University at Montgomery