Looking In, Looking Out: Mapping Chinese Exclusion and Imperial Expansion in a San Francisco Photographic Collage

PDF: Hong, Looking In, Looking Out

In Yale University’s Beinecke Library, the object is catalogued under the title Collage of nine photographic images from San Francisco printed on silk (fig. 1). Its physical description reads: “1 print: cyanotype, silk; 45 x 46 cm.” The maker is not identified; the year is tentatively dated 1900.1 As a historian of photography with an interest in alternative photographic processes, I was curious to view a cyanotype collage on silk; I had never come across this specific combination of technique and material before.2 A librarian handed me a large folder, within which the cloth had been stored flat. Upon opening it, I saw a single square of silk, about the size of a large handkerchief, light to the touch. The word “LUSTRAL” was printed on its back, suggesting that the fabric once possessed a sheen that it had since lost. Its edges were fraying, and time had yellowed the cloth. Creases in the fabric indicated that it had been folded at some point in its prearchival life.

The collage features nine cyanotype photographs arranged in an uneven grid. Although they vary in size, they fit neatly within the cloth’s boundaries, each image abutting the next. The photographs were probably printed one by one; after sensitizing the silk with a solution of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate, the photographer might have placed the silk into a printing frame and exposed each glass negative in succession, blocking off the rest of the fabric from sunlight. After exposing each image, the photographer would have washed the cloth in water to remove any unexposed iron salts and reveal the Prussian blue color created by the interaction of light and chemistry.

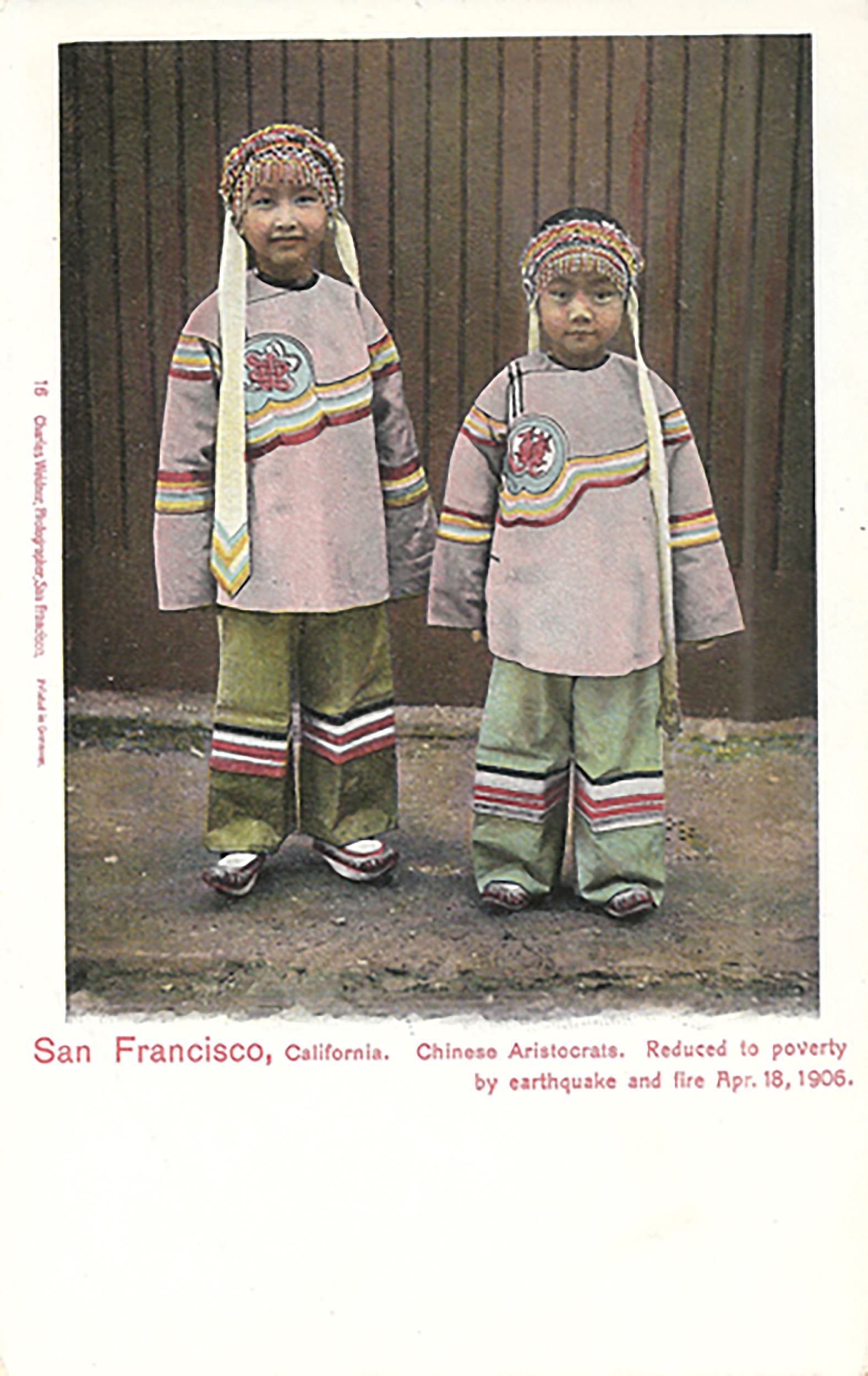

I began to orient myself with textual clues written on the photographic negatives, now printed on the cloth. The upper-center image, inscribed “The Golden Gate S.F.,” depicts Golden Gate Strait. The lower-center image, “‘Breakers’ near the Cliff House S.F.,” led me to believe that the central image, which is the collage’s largest, might represent Cliff House itself. This is indeed the case: rebuilt in 1896 by Adolph Sutro, a man who made a fortune in silver from Nevada’s Comstock Lode, Cliff House existed as a Victorian château until it burned to the ground in September 1907.3 The central photograph of Cliff House and its southern strand, Ocean Beach, populated by leisure seekers, visually anchors the surrounding views. At the top left, a large landmass covered in vegetation spouts a thin waterfall that cascades into a body of water. Similar contemporary views suggest that this is a photograph of Strawberry Hill, an island in the middle of Golden Gate Park’s human-made Stow Lake. At the top right, couples stroll along a tree-lined promenade; comparison with contemporary souvenir postcards reveals this to be Palm Avenue in Sutro Heights, a park the silver baron developed on his estate. Two other photographs flank the central image. On the left, a father and his two children hold hands in a Chinatown street. On the right, two girls are dressed in traditional Chinese holiday clothing; they were likely photographed on a festival day.4

I was immediately struck by the racial dichotomy that the photographic collage proposed. The picturesque landscapes of beach and promenade, dominated by tourists in Western-style dress, contrasted with the full-frontal, pseudo-ethnographic studies of the individuals in Chinatown, delivering their bodies to the viewer’s gaze.5 Given that San Francisco’s population was about 95 percent white in 1900 and that its Chinatown was a safe haven for a Chinese population accounting for 4 percent of the city’s inhabitants, I read the collage as materializing a binary between white and Chinese, American and alien.6 As Yong Chen shows, at the turn of the twentieth century, San Francisco’s Chinatown “stood as a site of comparison: one between progress and stagnation, between vices and morality, between dirtiness and hygiene, and between paganism and Christianity.”7 Hanging on opposite sides of the central image of white leisure, the Chinese subjects take on what Anne Cheng calls an “ornamental personhood,” in which race is made legible through the body’s artificial, supplementary surfaces and read against a picture of normative whiteness.8

There is a certain shame, Tina Campt observes, that accompanies research in the visual archive. In an attempt to glean signs of culture and class from the photographic subject, one examines the body’s exterior for identifying markers, repeating the process of racial formation.9 In the library, I could not help but feel that my scrutiny of these figures in Chinatown, my desire to know them, rubbed uncomfortably against the photographer’s own sovereign gaze, even while, as a Chinese American, I felt a strong sense of identification with them. However, my encounter with their likenesses only underscored to me how little I knew. I was wary of making strong claims about the material realities and inner lives of the figures depicted in the photo-cloth. While the classed and gendered dimensions of nineteenth-century anti-Chinese immigration laws meant that most Chinese children in San Francisco around 1900 would have been children of merchants, an almost exclusively male occupation, it is also true that in the era of Chinese exclusion (1882–1943), an estimated 300,955 Chinese people—men, women, and children; merchants and laborers; citizens and noncitizens—gained admission to the United States.10 The plurality of their identities and experiences makes knowledge claims about the individuals in these pictures unstable at best.

Nevertheless, I wondered: What did Pacific seascapes of the tourist photographs of white bourgeois leisure and the pseudo-ethnographic pictures of Chinese individuals have to do with one another? Who took these photographs and printed them on silk, and for what purpose? Comparing the cyanotype images with contemporary souvenir postcards, I identified a potential maker: Charles Weidner (1867–1940), a German émigré who established a reputation in San Francisco in the 1890s as a photographer of tourist views. One of his widely reproduced photographs, The Cobbler, featuring a Chinese shoemaker at work, was the frontispiece to Camera Craft’s inaugural issue in May 1900. The three photographs in the Beinecke photo-cloth’s central row are images that Weidner took in 1902 and reproduced as picture postcards, an extremely popular format in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.11 The images of individuals in Chinatown circulated within a genre of tourist postcards that featured racial types, reproducing imperial power dynamics by appealing to white, middle-class European and US audiences.12 Weidner captioned the postcard versions of the photographs on the photo-cloth “Chinese girls” and “Street in Chinatown” (fig. 2), respectively, emphasizing the subjects’ racial difference. There are inconsistencies between the latter postcard and the image that appears on the Beinecke photo-cloth, however. The family is pictured in different configurations, indicating that Weidner posed them and took multiple photographs. In the postcard, it appears that a figure has been added to the background, a common liberty taken by postcard printers.

Although Weidner took the original photographs, it is difficult to definitively attribute the silk object to him. In this period, photographs were widely “borrowed” and reproduced by other publishers without permission. Not only were Weidner’s own pictures cribbed, but Weidner also took from others. In one instance, he appropriated an image of seals near the San Francisco coast from an Isaiah West Taber photograph, which was a cropped version of a stereoview by Carleton Watkins.13 This photograph has also found its way onto the bottom left of the silk cloth. Weidner also produced a postcard depicting a distant view of Seal Rock, a small rock formation near Cliff House; the same image appears at the bottom right of the collage. Given that Weidner produced postcard versions of at least five of the nine photographs on this cloth, I hypothesize that he produced this object sometime in 1902 or later. It is likely, given that Weidner was a prolific photographer of San Francisco, that he took the other photographs as well. He printed very similar postcards of Strawberry Hill and Palm Avenue, and the handwriting visible from the photographic plates believably matches handwriting on other plates that bear Weidner’s name. However, I will refer to the object as the “Beinecke photo-cloth” to acknowledge its authorial uncertainty.

Although there is much we may not know conclusively about this object, the Beinecke photo-cloth shows how attending to the specificities of photographic formats, techniques, and materials allows surprising histories to surface. Here, the combination of photo collage, cyanotype process, and silk manifests the interconnections of tourist photography, blueprinting, domestic decoration, the global silk trade, and the Pacific telegraph cable. I have begun to think of the Beinecke photo-cloth as a conceptual map, one that deploys the logics of race and landscape to create a sense of belonging for an assumed white viewer. It is a domestic object that looks simultaneously inward and outward, containing the racialized subject even as it seeks to expand its reach.

The silk object interweaves multiple images on a single plane. Unlike photography albums, which could be read narratively, the Beinecke photo-cloth asks to be read as a kind of constellation or hyperimage, an assemblage of images that forms a new overarching unit.14 Taken together, the photographs present two modes of San Francisco leisure. Cliff House, Ocean Beach, and the nearby Sutro Baths attracted great crowds of San Franciscans on Sunday excursions. In contrast to these spaces, which were associated with hygiene and fresh air, antidotes to the diseases associated with urban centers, Chinatown was a popular “slumming” destination for white tourists seeking scenes of exoticism and vice; the neighborhood was frequently described as a source of pollution and a public health threat.15 The perspective of the oceanside images mimics the gaze of the beachgoer, who lounges on the sand and looks to the Pacific; recession into depth creates a sense of freedom, both of movement and of vision. In the photographs of Chinatown, however, the camera renders the Chinese figures mute subjects, presenting their still bodies as surfaces to be read.16 In this period, large numbers of white photographers explored Chinatown, taking advantage of an unequal power relation to capture stereotypical images of an Orientalized subculture.17 The Chinese, then, are not considered part of the leisure class but rather envisioned as pendants to it.

If my dating of the photo-cloth is correct, it was created in the middle of Yellow Peril discourse. After having relied on Chinese labor for the exploitation of mines—including the Comstock Lode, which generated Sutro’s wealth—and the construction of the transcontinental railroad, anti-Chinese labor activists and politicians in the West sparked a national movement to curb Chinese immigration. Beginning in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act instituted an absolute ban on Chinese laborers immigrating to the United States, leading to a dramatic population drop.18 The legislation was renewed in 1892 and extended indefinitely in 1904.19 The act excluded Chinese people who had settled in the United States from citizenship, rendering them permanent aliens; anyone who left the country could not reenter without proper certification. It also gave law enforcement officials the authority to detain any Chinese person suspected of having unlawfully entered the country and to deport them if found guilty.20 In San Francisco, politicians enacted legislation to control the Chinese population within the city. The Sidewalk Ordinance of 1870 banned the traditional Chinese method of using poles to carry bags and baskets. The Queue Ordinance of 1876 required imprisoned Chinese to cut their braids, which ironically would also prevent them from returning to China’s strict Qing society.

In this hostile environment, popular media imagined Chinatown as a colony in the city’s interior, portraying it as both mesmerizing and repulsive.21 Artists and photographers exoticized the neighborhood, interpreting signs of poverty as picturesque ruins. As painter Theodore Wores opined in 1889, “Americans are not fond of John Chinaman. . . . The vulgar hardly think him a man at all, and the better classes are revolted by his habits. But he and his surroundings make grand pictures, all the same.”22 The resourcefulness and resilience of Chinatown residents were interpreted as acts of ”degradation” and “loss of virtue.” Writer Robert Howe Fletcher described additions that immigrants made to existing architecture—picket fences to defend against “police and neighborhood feuds,” balconies and partitions to increase living space and provide privacy, painted walls and ornamented shop signs—as “a show of barbaric gorgeousness.”23 Photographer Arnold Genthe produced images of Chinatown depicting it as San Francisco’s “underworld,” whose “dark alleys” contained “drug addicts and suspicious characters of all sorts.”24

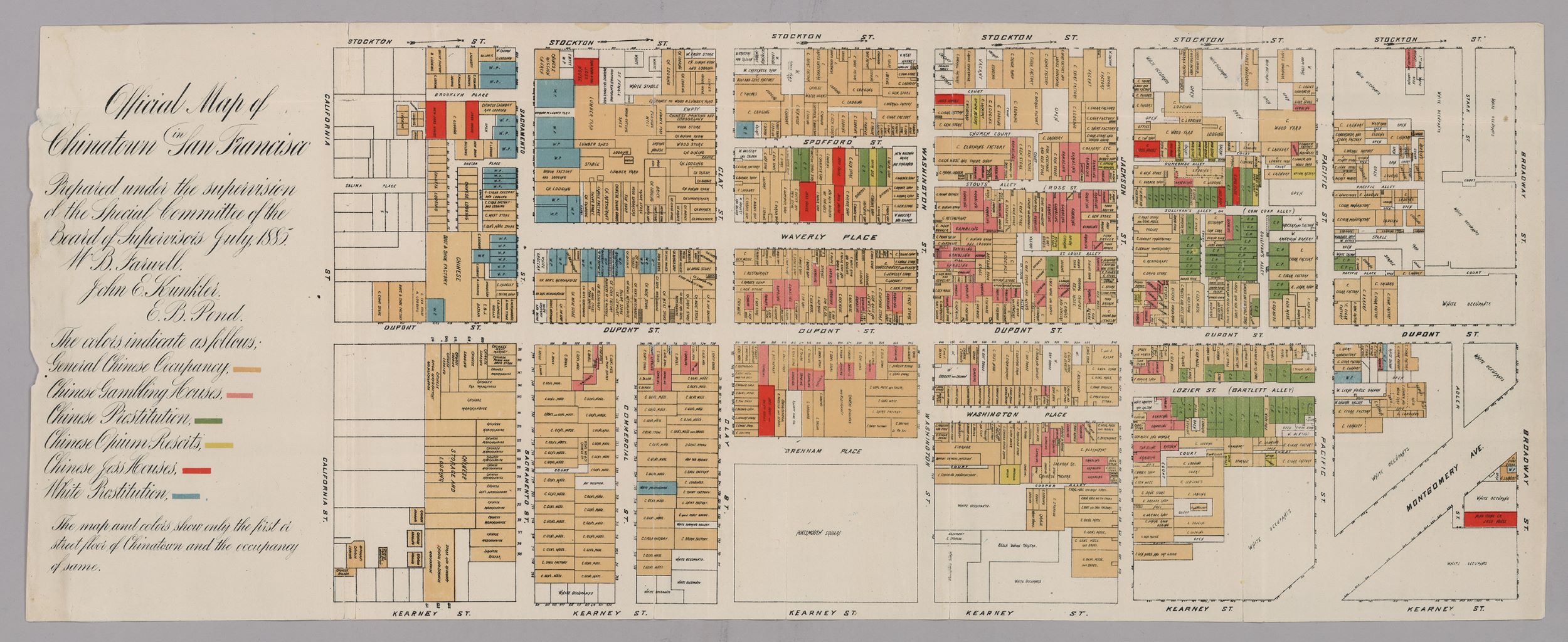

The Beinecke photo-cloth participates in this milieu. The images’ sharp frames formally replicate the city’s racial divides, materializing a form of visual containment. Considering that the cyanotype was at this point the dominant medium for the reproduction of geographical and architectural maps, we might view the collage as performing the work of spatial coordination and exclusion, bringing a group of images into relation and simultaneously marking their divisions.25 Chinese families encountered legalized segregation in schools and facilities, such as theaters and restaurants, in this period. (Sutro Baths was the subject of an early civil-rights battle in 1897, when an African American man named John Harris sued Sutro for denying him entry to the pools. Although he won the case, little changed at the baths, and de facto segregation persisted in public bathing spaces for decades.)26 Chinatown’s physical boundaries were also scrutinized; white residents objected to the neighborhood’s presence in the heart of San Francisco, and anti-Chinese politicians advocated for its removal and relocation to a segregated district.27 An 1885 “Official Map of Chinatown in San Francisco,” issued by a special committee appointed by the city’s Board of Supervisors, delimited a twelve-block area as the neighborhood’s border, even as the accompanying report acknowledged that the Chinese population exceeded its bounds (fig. 3). The committee highlighted gambling houses, brothels, opium dens, and joss houses in various colors in an attempt to depict Chinatown as a “moral purgatory.”28 Throughout the exclusion era, immigration raids were conducted frequently on Chinese places of business, as well as private residences. As the sociologist Mary Coolidge remarked in 1909, “All Chinese are treated as suspects, if not as criminals.”29 In this threatening sociopolitical climate, the photo-cloth suggests differential mobilities: the stillness of the Chinese figures before the camera’s lens, the repose of the beachgoers, and the movement of the photographer, who ventures easily from Chinatown to park to beach. (The pendant images of Chinatown also function as a kind of gateway to the ocean, just as San Franciscans might have moved from the docks on the city’s east side through Chinatown to reach the wealthier neighborhoods surrounding Cliff House in the west.) It is telling that the collage visually separates Chinese individuals from cultivated spaces that were associated with the virtues of public health, prosperity, and social cohesion.30 They were defined as noncitizens, and so their appearance would have been incommensurable with understandings of a homogenous national identity.

Though we can consider the Beinecke photo-cloth as a kind of map that creates a dichotomy between Chinatown and ocean, east and west, we must also take into account the blueprint’s use as a form of domestic decoration. Printing cyanotypes on cloth was a common craft practice at this time. In 1895, one commercial photographer wrote that the “blue-print” was a simple process that could be used “on cotton fabrics as well as paper, thus giving us the power of producing pictures or designs in blue and white, on muslin or similar cloth, at a surprisingly small cost.”31 Another use, of particular interest to “lady readers” of the journal, was “printing pictures or designs on cloth for fancy household decoration.”32 One popular form of domestic cyanotype decoration was the quilted photo–pillow slip. Consisting of printed squares, usually containing travel snapshots, the pillow tastefully and inexpensively commemorated family and leisure, nostalgically employing a preindustrial craft even as it embraced modern means of mechanical production.33 In 1891, a photographer named Adelaide Skeel speculated that if a “large enough printing frame” could be devised, “half a dozen negatives could be fitted, criss-cross, and all printed on a large sheet of cardboard or yard of cloth, so that the effect would be of a mounted group.”34 The photo-cloth closely resembles her description, suggesting that the maker was experimenting with the cyanotype collage as a form of home décor.

The Beinecke photo-cloth materializes a mode of homemaking that presents San Francisco as belonging to the white viewer. Weidner’s photographs not only present the city’s sights under the white gaze, but they also hint at an understanding of what white, heteronormative families looked like in contrast to the kinship structures of Chinese immigrants. His photographs of Chinese children do not signify Chinatown as a seedy underbelly, as many of his other photographs do; rather, they represent the converse of the Yellow Peril: the Asian as ornamental, docile, domesticable. Chinese children were a relatively rare sight in the city between 1860 and 1920, since they amounted to no more than 11 percent of the Chinese population in San Francisco.35 But pictures of Chinese children circulated widely in the booming postcard industry, and these images played an important role in the politics of immigration and labor.36 Anti-Chinese politicians critiqued the nomadic lifestyle of the “family-less” Chinese bachelor, contrasting him with his European counterpart, who typically brought his nuclear family with him or established one after settling in the United States.37 (In 1900, women and girls made up around 15 percent of the Chinese population in San Francisco.)38 Congressman Thomas Geary described Chinese immigrants as isolated “birds of passage” who “establish no domestic relations here, found no homes and in no wise increase or promote the growth of the community in which they reside.”39 Nineteenth-century propaganda denied the existence of Chinese family life as a way of illustrating the deviant culture of San Francisco’s Chinatown in contrast to a white, middle-class, domestic ideal.40 Images of children in Chinatown ran counter to the pervasive idea of the bachelor community. As the picturesque side of peril, they represented a population that could be commodified and tamed.41 In the Beinecke photo-cloth, the presence of white families and heterosexual couples in the central and upper-right images accentuates the maternal absence in the Chinatown pictures, marking the incompleteness of a normative nuclear family.42 At the same time, printing the Chinese figures onto the silk cloth domesticates them, simultaneously internalizing the Other and consolidating a white national identity.

The photo-cloth’s materiality also situates it within the context of global trade and US imperialism. The maker’s use of silk, a high-value commodity that was about fifty times the price of cotton or hemp, suggests that the object was intended to be a marketable souvenir for domestic display.43 By 1900, the United States, in the middle of a silk-manufacturing boom, had become the world’s number one importer of raw silk, mainly from China and Japan. The industrialization of silk manufacturing and the completion of the transcontinental railroad spanning the United States allowed for the importation of raw silk from East Asia to San Francisco and its transportation to factories in the Northeast.44 The photo-cloth visually gestures to the Pacific and to the Chinese immigrant as if to index the globalized origins of its material support. If silk places this object at a critical node of global trade, the photo-cloth’s multiple seascapes reinforce this connection, signaling the American dream of ceaseless westward expansion. At the turn of the century, the nation was fixated on the Pacific as a region of development; the federal government enacted exclusionary immigration policies at the same time that it aggressively expanded its own markets. In 1899, for instance, US Secretary of State John Hay sent the first of his “Open Door” notes, which established a tacit agreement between imperial interests to not interfere with one another’s trade with China. The United States secured its borders from an influx of cheap labor while seeking to exploit new resources.45

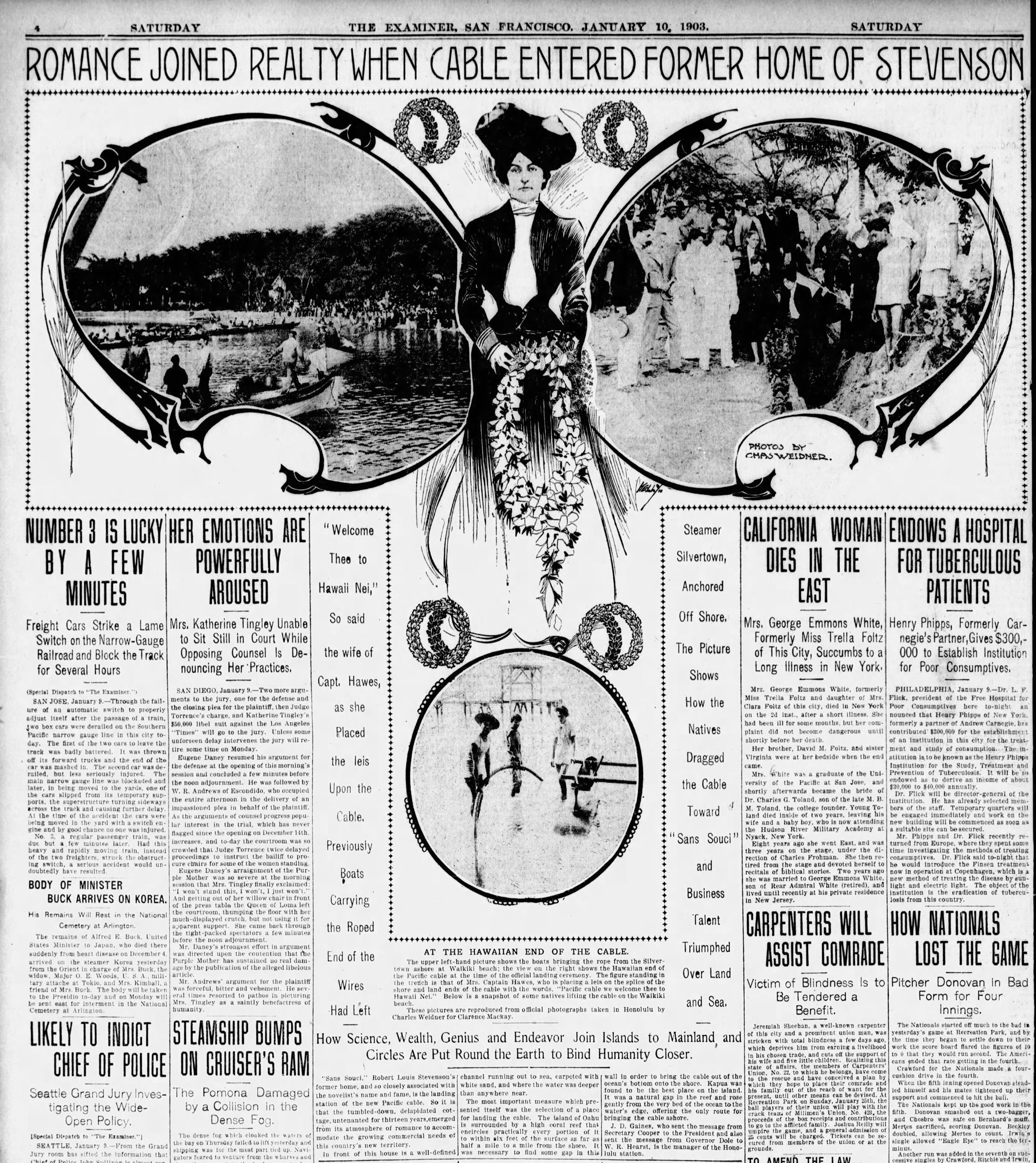

Weidner’s movements tie the history of US expansionism to the beach depicted at the center of the Beinecke photo-cloth. In mid-December of 1902, the photographer traveled to Honolulu to photograph the laying of a telegraph cable from San Francisco to Hawai‘i by the Pacific Commercial Cable Company. The cable ship Silvertown began its voyage off the San Francisco coastline: before a crowd of fifty thousand spectators, a crew laid the first section of cable at Ocean Beach, just south of Cliff House.46 Carrying 2,500 miles of cable in three massive tanks, Silverton steamed to Honolulu, where the connecting section of cable was laid at Sans Souci, the former home of Robert Louis Stevenson.47 An article in the Examiner (fig. 4) featuring Weidner’s photographs makes much of this fact, describing the telegraph cable’s arrival as the fulfillment of Stevenson’s romantic adventure tales, made possible by “Business Talent.”48 This undersea cable was the beginning of a network that would directly link the United States to its newly annexed colonies, Hawai‘i and the Philippines, as well as its growing markets in China and Japan.49 “It is as the herald of our commercial conquest of the Orient that the cable has its greatest significance,” Gunton’s Magazine reported in 1903.50

Weidner’s involvement with the Pacific telegraph cable immerses the Beinecke photo-cloth in an imperial context. Like the spliced undersea cable, the lustrous silk materially binds East Asian labor to the American home. Perhaps its shine, along with the cyanotype’s blue, would have evoked the ocean’s shimmer, paradoxically signifying vast distance and invisible connectivity. After his Honolulu trip, Weidner returned to San Francisco on the steamship Korea, which brought with it 5,140 tons of freight, including rice and raw silk. Its steerage passengers included 126 Japanese and 96 Chinese individuals.52 While Weidner’s beachside pictures appear to be straightforward landscapes produced for a tourist market, the photo-cloth belies the photographer’s own awareness of the coast as liminal space where migration, trade, and expansion were actively managed.

As blueprint, domestic decoration, and imperialist object, the Beinecke photo-cloth demonstrates a multidirectional movement, looking inward and outward, at once visually containing the Chinese in San Francisco’s interior and projecting Western presence in the Pacific. The cloth constitutes a visual economy in which the tourist, pseudo-ethnographic, and landscape photograph simultaneously convey and conceal the dynamics of racial formation and imperial expansion, sublimating them as a home good for a white, bourgeois subject. Invisible yet present in this collage are the exclusion of Chinese immigrants and the United States’ push into the Pacific; though absent from the frame, these contexts silently structure the photographic assemblage’s significance.

Considering Weidner’s photographs together with their technical and material histories, we come to a better understanding of how this object manifests a vision of white national belonging and possession. Yet there is much more to be said about this object: its frayed edges point to loose ends, unresolved histories. I will close with two threads I would like to follow, threads with no current resolution but that, I believe, deserve further research and reflection.

There is more to investigate about the publication and circulation of Weidner’s individual photographs as tourist postcards. Weidner reprinted numerous pictures of Chinatown and Chinese people in the early twentieth century; the ways in which he captioned and recaptioned them speak volumes about how he manipulated his photographs’ significance. After the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, Golden Gate Park served as a sanctuary for unhoused residents, but Chinese people were segregated into camps in the Presidio and Oakland.53 Ironically, while their bodily movement was restricted, the circulation of their likenesses continued apace. Weidner promptly reprinted postcards of his photos of the Chinese girls with a new caption: “Chinese Aristocrats. Reduced to poverty by earthquake and fire Apr. 18, 1906” (fig. 5). Other postcards describe Chinese residents affected by the earthquake and fire as “rendered homeless” and “without home.” The photographer’s treatment of Chinese individuals after the earthquake contrasts starkly with photographs he took of white San Franciscans, who are typically pictured in relaxed poses, resting among their salvaged possessions (fig. 6). While Weidner depicted the white residents with their belongings, ready to reoccupy and rebuild the city, he could no longer access his Chinese subjects; he therefore repurposed the tourist photograph of the Chinese children as a nostalgic image of an expendable race.54

Weidner’s need to recaption his old images to print new postcards indicates that the subjects he photographed ultimately eluded his gaze. They lived beyond surveillance, beyond the image’s frame, not as “birds of passage” but, rather, as people who put down roots and shaped the future of Chinese American communities. Acknowledging the fact that Weidner’s camera could never fully capture these individuals, that their presence before its lens was only fleeting, is one way to read the photographer’s images against the grain, to recognize them as pointing toward unknowable histories outside their frames. As Z. Serena Qiu puts it, this interpretive method aids the photographic subject’s ongoing “escape from surveillance and further epistemological extraction.”55 I wonder, however, if there is more to say about what we do see in these pictures. After all, Weidner’s photographs of Chinatown, while capitalizing on an image of an exotic Other, also evince these individuals’ insistence on the survival of their cultural heritage. Chinese people did not wear their precious holiday garments to be objectified by the tourist gaze: they did so to perpetuate their cultural identities, histories, and spiritual beliefs.56 In an era when Chinese immigrants were criticized for their “failure” to assimilate into normative white US society, when their non-Western dress and physical appearance made them targets of racist violence, and when their children were taught to run from the white photographer’s camera, perhaps the decision to appear before the camera bearing the markers of unassimilability was its own act of defiance.57

As much as I have argued that the Beinecke photo-cloth is structured by a disciplinary visual rhetoric, this rhetoric need not overdetermine our interpretations of its images. Considering the subjects’ own insistence on cultural difference transforms the photographs into “contested sites of encounter”—in this case, sites at which the photographer sought to flatten and commodify what the subjects actively preserved.58 As Saidiya Hartman writes, the archive sets limits on the knowable, but it also contains portals into counternarratives, each one a potential “revolution in a minor key.”59 If we read Weidner’s Chinatown photographs as documents in which—or in spite of which—Chinese people assert heterogeneity, fashion their own senses of being and belonging in the United States, what interpretive possibilities might emerge?60 With these loose threads, I hope to continue unraveling this object, open to the alternative histories to which they may lead.

Cite this article: Kevin Hong, “Looking In, Looking Out: Mapping Chinese Exclusion and Imperial Expansion in a San Francisco Photographic Collage,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9, no. 2 (Fall 2023), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.18165.

Notes

My thanks to the colleagues and comrades who have supported this article at various stages, including Angela Chen, Michelle Donnelly, Alex Fialho, Manon Gaudet, Michaela Haffner, Elizabeth Keto, Jennifer Lu, Sophia Kitlinski, Nathalie Miraval, Marina Molarsky-Beck, and Yechen Zhao. I am also grateful to Anthony Lee, George Miles, Stephen Ness, and Wendy Rouse for sharing their insights at crucial moments in the research process. And I am deeply appreciative of the editors at Panorama—Emily Burns, Annika Fisher, Liz McGoey, Oliver O’Donnell, and Jessica Routhier—for the care they have shown to this work.

- The Beinecke acquired this object in 2018 from William Reese Company, a rare books and manuscripts dealer in New Haven, CT. The dealer file does not contain any more information about its provenance. ↵

- This research sprang from preliminary work I conducted on my dissertation, which explores the history of alternative and experimental photographic processes. It now forms a part of a separate research project that focuses on images of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. ↵

- This incident was unrelated to the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. ↵

- From the early 1890s to 1906, many non-Chinese visited Chinatown to take photographs, often on Chinese holidays. Anthony Lee, Picturing Chinatown: Art and Orientalism in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 104; Wendy Rouse, “Postcard Images of Chinese: American Childhood and the Construction of a New Chinatown,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 53 (Spring 2010): 8. ↵

- Photographers who visited Chinatown in the late nineteenth century viewed the neighborhood as “a text to be read for what it could say about racial difference.” Anthony W. Lee, “Picturing San Francisco’s Chinatown: The Photo Albums of Arnold Genthe,” Visual Resources 12, no. 2 (January 1996): 116. ↵

- “Twelfth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1900,” United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1901/dec/vol-01-population.html. Yong Chen notes that the word “white” was widely used as a term of identification in nineteenth-century anti-Chinese literature. Yong Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 1850–1943: A Trans-Pacific Community (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000), 67. ↵

- Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 99. ↵

- Anne Anlin Cheng, Ornamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 3. ↵

- Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 125–28. ↵

- Erika Lee, “Defying Exclusion: Chinese Immigrants and Their Strategies During the Exclusion Era,” in Chinese American Transnationalism: The Flow of People, Resources, and Ideas Between China and America During the Exclusion Era, ed. Sucheng Chan (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 1–10. The exempt categories in the exclusion laws included merchants, students, teachers, diplomats, and travelers, categories that applied almost exclusively to men in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century China. However, in 1900, hundreds of Chinese men in San Francisco, not all of them merchants or professionals, had wives and children with them. Sucheng Chan, “Against All Odds: Chinese Female Migration and Family Formation on American Soil During the Early Twentieth Century,” in Chen, Chinese American Transnationalism, 42. ↵

- In 1902, Weidner published postcards with his business partner, William Goeggel. The partners sent Weidner’s photographs to a postcard manufacturer in Germany to be printed. In 1903, Goeggel’s name stops appearing in the postcard imprints, suggesting that their business relationship ended. Frank Sternad, “Charles Weidner: Photographer and Postcard Publisher,” San Francisco Bay Area Post Card Club, 5, accessed July 10, 2023, http://www.postcard.org/charles-weidner-postcard-publisher.pdf. ↵

- On picture postcards at the turn of the twentieth century, see Christraud M. Geary and Virginia-Lee Webb, eds., Delivering Views: Distant Cultures in Early Postcards (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998). ↵

- Taber acquired the rights to Watkins’s early negatives when Watkins declared bankruptcy in 1874. While Watkins originally noted that the photograph was taken at the Farallon Islands, Taber recaptioned the photograph “The Seal Rocks near Cliff House, San Francisco.” ↵

- Felix Thürlemann, More than One Picture: An Art History of the Hyperimage (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2019), 1. ↵

- Ivan Light, “From Vice District to Tourist Attraction: The Moral Career of American Chinatowns, 1880–1940,” Pacific Historical Review 43, no. 3 (1974): 367–94; Nerea Feliz Arrizabalaga, “Adolph Sutro’s Interior Ocean: A Social Snapshot of 19th-Century Bathing in the United States,” Architectural Histories 9, no. 1 (2021): 4–12; Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 85. ↵

- On the construction of photographs for ethnographic, colonial, and racist purposes, see Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art 9, no. 1 (Summer 1995): 38–61. ↵

- Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 104. ↵

- In 1890, the Chinese population in San Francisco was twenty-six thousand; by 1900, it was below fourteen thousand. Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 120. Anti-Chinese sentiment was widespread among Californians, but different groups had different agendas in their support of exclusionary laws. Capitalists encouraged anti-Chinese hostility, understanding that such an environment would make Chinese labor even more exploitable. Exclusion also helped to unify the white labor movement and allowed white ethnic workers to emphasize their whiteness in contrast to a demonized racial Other. Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 46. ↵

- The law was repealed in 1943, though a quota that limited immigration to 105 Chinese individuals remained. ↵

- Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 224. As Lee writes, Chinese immigrants were “the first to be excluded on the basis of their race and class” and “the first group to be classified as deportable.” ↵

- Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 19. ↵

- “Mr. Theodor Wores,” Star (London), July 9, 1889; quoted in Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 85. ↵

- Robert Howe Fletcher and Ernest C. Peixotto, Ten Drawings in Chinatown (San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1898), 3. ↵

- Arnold Genthe, As I Remember (London: George G. Harrap, 1937), 33. ↵

- The Klondike gold rush of the 1890s popularized blueprints as a cheap form of map reproduction; the cyanotype was the primary map-printing technology until diazotype replaced it in the 1940s. Geoffrey Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph (Munich: DelMonico Books-Prestel in association with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2016), 14. ↵

- “Drew the Color Line: As a Result Adolph Sutro is Called Upon to Pay Damages,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 17, 1898, 11; “John Harris Sues Adolph Sutro for Discrimination,” National Park Service, accessed August 20, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-harris-sues-adolph-sutro-discrimination.htm. ↵

- Chen, Chinese San Francisco, 58. ↵

- “Report of Special Committee of Board of Supervisors of San Francisco on the Condition of the Chinese Quarter and the Chinese in San Francisco,” in Willard B. Farwell, The Chinese at Home and Abroad (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft & Co, 1885), 65. ↵

- Lee, At America’s Gates, 230–31; Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York: Holt, 1909), 324. ↵

- Terence Young, Building San Francisco’s Parks, 1850–1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 3. ↵

- J. Will Barbour, “The Muslin Blue Print,” American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac, January 1, 1895, 43. ↵

- Barbour, “Muslin Blue Print,” 43. ↵

- Erin Garcia, “Nothing Could Be More Appropriate,” Afterimage 29, no. 6 (May/June 2002): 14–15. ↵

- Adelaide Skeel, “Something More About the ’Blues,’” Photographic Times and American Photographer, January 30, 1891, 54. ↵

- Wendy Rouse, The Children of Chinatown: Growing up Chinese American in San Francisco, 1850–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 3. ↵

- Rouse, “Postcard Images of Chinese,” 6. ↵

- Rouse, Children of Chinatown, 15. ↵

- Chan, “Against All Odds,” 39–45. ↵

- T. J. Geary, “The Other Side of the Chinese Question,” Harper’s Weekly, May 13, 1893, 458. ↵

- Rouse, Children of Chinatown, 2. ↵

- On the aesthetics of domestication, see Thy Phu, Picturing Model Citizens: Civility in Asian American Visual Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012), 26–53. ↵

- The Page Law of 1875 and later ban on the spouses of Chinese laborers severely curtailed the immigration of Chinese women. However, Chinese women did immigrate to the United States, usually as the wives or daughters of a US citizen or an immigrant in an exempt category. Lee, “Defying Exclusion,” 6. Many Chinese women were also forced to immigrate to the United States to work as prostitutes. Many of these women eventually married and had children. As Sucheng Chan argues, an assumed dichotomy between prostitutes and married women did not necessarily exist (“Against All Odds,” 55). ↵

- Debin Ma, “The Modern Silk Road: The Global Raw-Silk Market, 1850–1930,” Journal of Economic History 56, no. 2 (1996): 346. ↵

- Ma, “Modern Silk Road,” 331–32. ↵

- Colleen Lye, America’s Asia: Racial Form and American Literature, 1893–1945 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 20. ↵

- “The Pacific Cable,” Gunton’s Magazine, August 1903, 55. ↵

- William H. Crawford, “The New Pacific Cable from San Francisco to Honolulu, Hawaii,” Marine Engineering 8, no. 2 (February 1, 1903): 57. ↵

- “Romance Joined Realty {sic} When Cable Entered Former Home of Stevenson,” San Francisco Examiner, January 10, 1903, 4. ↵

- “Binding the United States to its New Possessions,” Leslie’s Weekly, January 1, 1903, 17. The undersea cables themselves were insulated with gutta-percha, a natural plastic harvested by killing trees in Southeast Asia. The huge demand for this resource in the later nineteenth century and its unsustainable harvesting by European colonial powers led to the near-extinction of the trees that made the telegraph industry possible. John Tully, “A Victorian Ecological Disaster: Imperialism, the Telegraph, and Gutta-Percha,” Journal of World History 20, no. 4 (2009): 559–79. ↵

- “Pacific Cable,” 55. ↵

- On the construction of colonial domesticity, see Vicente L. Rafael, “Colonial Domesticity: White Women and United States Rule in the Philippines,” American Literature 67, no. 4 (December 1995): 639–66. ↵

- “Big Pacific Liner Creeps Into Port,” San Francisco Examiner, January 10, 1903, 8. ↵

- Lee, Picturing Chinatown, 150. ↵

- Weidner’s nostalgic captions echo contemporary depictions of Indigenous Peoples as a “vanishing race.” See Christopher Lyman, The Vanishing Race and Other Illusions: Photographs of Indians by Edward S. Curtis (New York: Pantheon, 1982). ↵

- Z. Serena Qiu, “In the Presence of Archival Fugitives: Chinese Women, Souvenir Images, and the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11645. ↵

- Wendy Rouse, “The Limits of Dress: Chinese American Childhood, Fashion, and Race in the Exclusion Era,” Western Historical Quarterly 41 (Winter 2010): 451–71. As Yong Chen writes, “By wearing their ‘queer looking’ clothes and queue, Chinese immigrants made a constant statement of their ethnic identity” (Chinese San Francisco, 138). ↵

- In 1900, Arnold Genthe wrote that in his experience, “Chinamen have a very pronounced aversion to the camera.” Children, too, were “taught to run away from the black box.” Arnold Genthe, “The Children of Chinatown,” Camera Craft 2, no. 2 (December 1900): 99. ↵

- Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton, introduction to Photography, Anthropology, and History: Expanding the Frame (London: Routledge, 2016), 21. ↵

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019), xiii–xv, 59. ↵

- Lisa Lowe has considered Chinatown as a Foucaultian heterotopia, a “resistant locality” that challenges the hierarchical structures of other social spaces, in Immigrant Acts (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 122. ↵

About the Author(s): Kevin Hong is a PhD Candidate in the History of Art at Yale University.