Muholi: Risk and Reward at the Cummer Museum

Recently, I left the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art—where I had been the director for nearly twenty years—to accept the position of director and CEO of the Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens. The Cummer Museum, which was established nearly sixty years ago in Jacksonville, Florida, is one of the cultural gems of the city.1 On my first day in the office, in January 2021, I learned that the exhibition the museum planned to present in March 2021 had to be postponed. The national tour was delayed due to the global pandemic. Like many institutions around the country, the Cummer Museum was charged with the task of being nimble.

Countless people I met during my earliest days in Jacksonville shared their love of the Cummer’s historic gardens. Many others mentioned that their children participated in the Cummer Museum camps, classes, and summer programs. However, like many museums in this country, the Cummer Museum was historically perceived as an institution that was only for affluent donors. For this reason, it did not surprise me when some people—primarily Black and Brown people—explained that they have either not customarily visited or never visited the Museum. Over time—but especially in the last several years, due to strategic and concerted efforts to expand its reach—the Museum has become a more welcoming place.

The opening in the Cummer Museum’s exhibition schedule due to the cancellation of the touring exhibition presented several noteworthy opportunities: serve new residents flocking to Jacksonville during the pandemic; expand museum offerings by adding an exhibition featuring work by an internationally renowned contemporary artist from Africa or the African Diaspora; and further ongoing efforts to expand the museum’s reach and welcome new audiences. This shift in the schedule supported one of my board-approved objectives, which was to lead efforts to continue to reverse historic perceptions.2

I shared the Museum’s unexpected exhibition circumstance with Renée Mussai, the senior curator/head of curatorial & collections at Autograph London and a valued and trusted colleague. I asked if she would consider allowing the Cummer Museum to present Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, the powerful exhibition she curated in 2017, which garnered critical and popular acclaim.3 Autograph enthusiastically said yes, and Muholi quickly agreed. The Cummer Museum would be the final venue for this international traveling exhibition.

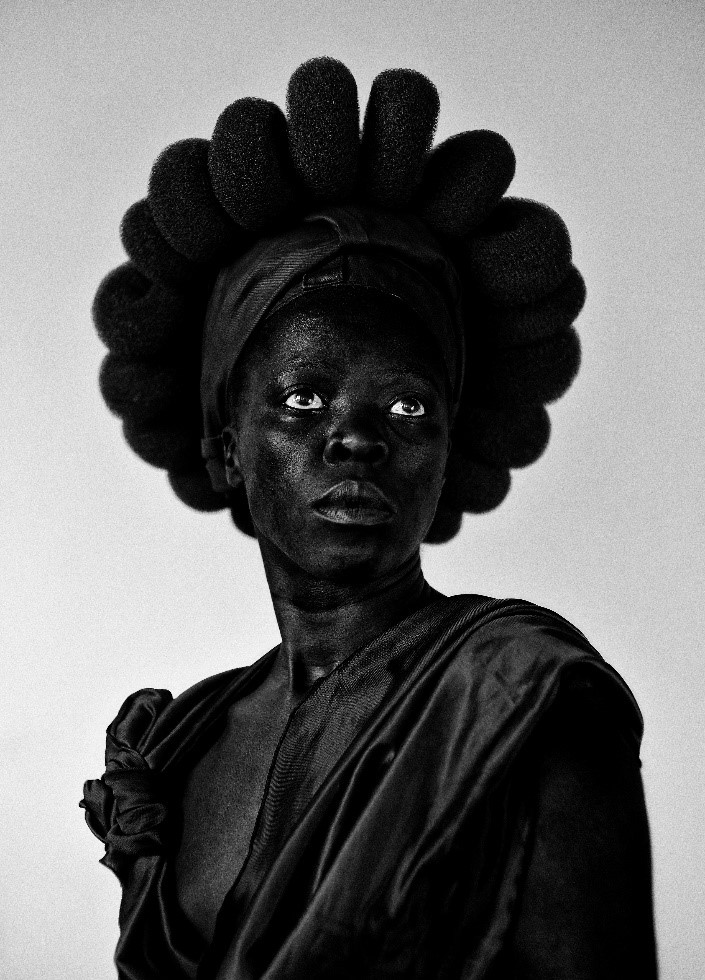

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972) is one of the most acclaimed photographers working today, and their work has been exhibited all over the world. Since the early 2000s, they have documented and celebrated the lives of South Africa’s Black lesbian, gay, trans, queer, and intersex communities. In 2012, Muholi turned the camera on themself and launched the ongoing series Somnyama Ngonyama, which translates to “Hail the Dark Lioness” from isiZulu, one of the official languages of South Africa. Muholi playfully employs the conventions of classical painting, fashion photography, and the familiar tropes of ethnographic imagery to explore contemporary identity politics. Each black-and-white self-portrait asks critical questions about social (in)justice, human rights, and contested representations of the Black body (figs. 1 and 2).

I am grateful for the invitation from Jacqueline Francis, PhD, to contribute to this Colloquium and reflect on the impact of this exhibition for two reasons. First, the resounding yes from Mussai and Muholi allowed the museum to amplify and accelerate its growing focus on equity. I am privileged to acknowledge that the board of trustees offered its full support. Staff members in every department galvanized resources and shifted gears without missing a beat in order to realize this project. Mussai and Bindi Vora, the curatorial project manager at Autograph, were fully engaged despite over-committed schedules.

Second, it allows me to reflect on several overlapping questions, which informed my thinking at that time: knowing that Somnyama Ngonyama differs significantly from other exhibitions in the Cummer Museum’s history, how would Jacksonville audiences, which have historically been conservative, respond to this work? What would be the best ways to encourage audiences to consider the critical topics that Muholi examines in their work, including hate crimes, equity, homophobia, transphobia, and the deep-seated injustices that have historically been enacted against the Black body, to name a few. In the spirit of being fully transparent, I must also admit that I questioned what long-term impact, if any, presenting the work of a queer nonbinary visual activist who identifies with they/them pronouns would have on me—an African American woman museum professional who had just arrived in Jacksonville. Finally, how would the Museum’s core audience and supporters perceive and receive me if Somnyama Ngonyama—which is a significant departure from previous exhibitions—was the first exhibition of my tenure?

Muholi has been illuminating global inequities for decades. Their probing and captivating self-portraits provide a meaningful context to consider and discuss historical inequities, which have come into greater focus in light of violent crimes against Black people and the civil unrest that ensued. The photographs bring these harsh realities to the foreground through the lone subject within the frame and the stark contrast between Muholi’s skin, which they darken in post-production, and the bright whites that they deliberately create. By incorporating an array of household props, such as latex gloves, washing machine hoses, safety pins, and scouring pads, and deliberately omitting context, Muholi requires viewers to decipher the images, read objects, and probe deeply in order to discover meaning.

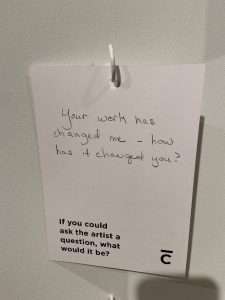

Somnyama Ngonyama has resonated with the Cummer Museum’s audiences in tangible ways (fig. 3). Moreover, it has provided a stunning vehicle through which to open meaningful and difficult conversations, in many instances with visitors who wouldn’t otherwise find reasons to talk to one another. The conversations that visitors have had with the visitor experience staff and docents alike are powerful and gripping. The programs—especially the Talk Backs, which are led by community leaders—have fueled exchange and been the source of deep understanding. I have witnessed people become overwhelmed as they enter the exhibition and burst into tears. The interactive station, which invites visitors to answer open-ended questions, has become a hub of exchange and respect (figs. 4 and 5).

Despite my initial hesitations about presenting Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness at the Cummer Museum, by and large, responses signaled that viewers were up to the challenges that this work demands and were willing to grow and stretch. Although Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness is a declaration and a call to action, each and every self-portrait requires Muholi to be vulnerable. By presenting this exhibition, the museum also took a risk and asked audiences to trust the process and reciprocate. Visitors responded with a resounding yes and were willing to be vulnerable in return. I am certain that the opportunity to present this exhibition was not mere happenstance. It has underscored that the rewards exceeded the risks by leaps and bounds.

Cite this article: Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, “Muholi: Risk and Reward at the Cummer Museum,” in “American Art Art History in the Time of Crises” Colloquium, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11934.

PDF: Brownlee, Muholi Risk and Reward

Notes

- For nearly sixty years, the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens has been committed to engaging and inspiring audiences through its art, gardens, and educational programming. A permanent collection of more than 5,000 objects and historic gardens on a riverfront campus offer nearly 160,000 annual visitors a truly unique experience on the First Coast. Nationall -recognized education programs serve adults and children of all abilities, and diversity and inclusion are woven into the fabric of the Museum. Cummer Museum website, accessed May 31, 2021, www.cummermuseum.org. ↵

- Over the years the Cummer Museum has endured significant hardship, including hurricane Irma, canceled plans to refurbish a building on an adjacent property due to a termite infestation, and leadership transitions. Shifting the exhibition schedule was in lockstep with an institutional history of resilience. ↵

- After Somnyama Ngonyama closed at Autograph, London, it traveled to the New Art Exchange in Nottingham, England (April 28–June 24, 2018). In 2018, I had the privilege of presenting the exhibition at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, where it made its United States debut. It then traveled to the Colby Museum of Art (February 14–June 9, 2019), the Seattle Art Museum (July 10–November 9, 2019), the Cooper Gallery at Harvard University (January 31, 2020–suspended due to COVID), and the Center for Visual Art at Metropolitan State University of Denver (January 8–March 20, 2021). Autograph, London published a limited-edition catalogue that features an interview with Muholi and insightful scholarly essays. ↵

About the Author(s): Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, PhD, is the George W. and Kathleen I. Gibbs Director and CEO of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens