Naming, Blaming, and Claiming: The Columbus Monument and the Struggle for Diversity Rights in Syracuse, New York

PDF: Borrman, Naming, Blaming, and Claiming

A person handed me a white glove stained in red paint and returned to the base of the statue, where fellow protestors had finished setting up the PA system. “The Columbus Monument must come down! It is an ongoing reminder of the city’s complacency with systemic oppression and colonialism. . . . Nobody is free until everybody is free!” demanded Alice “Queen” Olom in Syracuse, New York, on October 11, 2021.1 A few dozen protestors clapped while others nodded in agreement. Several dog walkers edged near the crowd, removing earbuds to better hear the commotion. I listened to the protestors from the steep staircase of the Beaux-Arts Onondaga Courthouse (fig. 1), designed in 1904 by local architect Archimedes Russell. From the elevated staircase, the crowd appeared small against the tall spires of Russell’s Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, which also stood along Columbus Circle, so named after the statue’s dedication in 1934. Protestors circled the bronze statue of the explorer, raised their red-stained gloves, and chanted, “Take it down!”

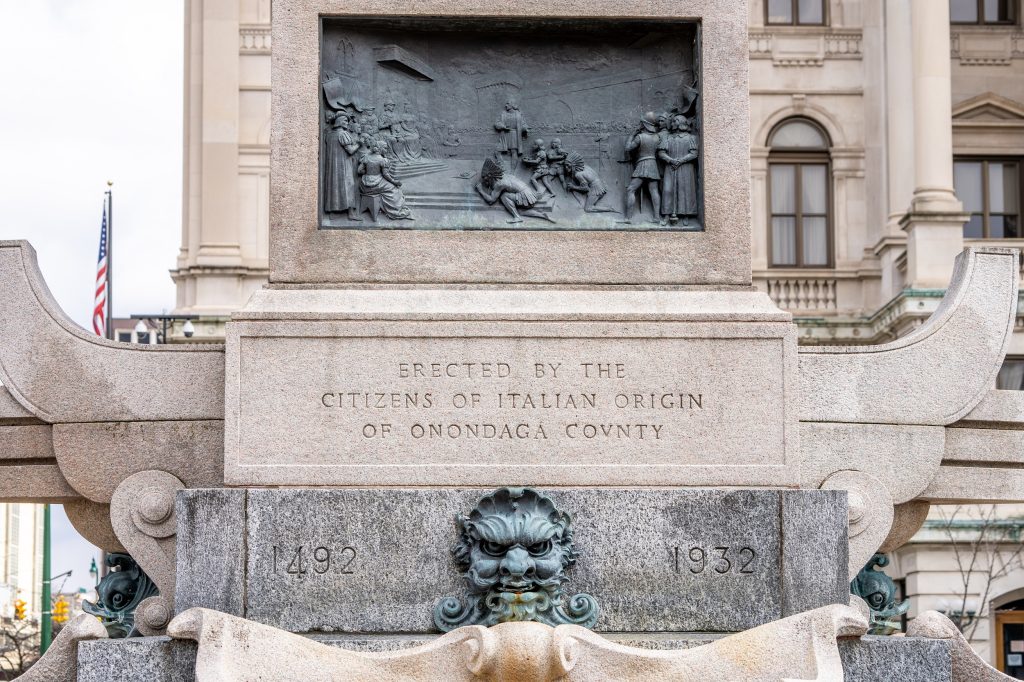

Earlier that morning, members of Syracuse’s Italian American community had gathered for their annual Columbus Day wreath-laying ceremony. A crowd of older men and women listened to a recording of the Italian and American national anthems while police stood guard at the corner of Montgomery and East Onondaga Streets. The police patrol was prompted by fear of vandalism and the presence of high-profile attendees, like US Representative John Katko, whose attendance signaled support for the Columbus Monument Corporation (CMC). Members of the CMC distributed lawn signs: “Mayor Walsh, Don’t Touch the Columbus Monument!” (fig. 2). While the CMC admitted that Christopher Columbus was an instrument of European conquest and colonization, they argued against the statue’s removal.2 “The right solution is to be additive, not destructive,” they advised, reasoning that the monument could remain in place if it were accompanied by “an ongoing series of artworks dealing with the themes of oppression and exclusion.”3

Since the 1990s, public demand for the removal of the Columbus Monument pitted Italian Americans against Indigenous groups and others who associate the explorer with imperial conquest and racialized violence. In October 2020, Syracuse Mayor Ben Walsh announced his plan to remove the Columbus statue and replace it with Heritage Park: a public square dedicated to multiple immigrant groups.4 In response, the CMC argued that the Columbus statue should remain since it is a symbol of Italian American heritage, with the explorer deserving a place among other ethnic heroes (fig. 3). They proposed that Columbus Circle might be improved by adding a monument to the Onondaga people of Central New York.

This notion that the Columbus statue’s association with racial injustice might be assuaged by “adding” effigies of other ethnic groups—in this case, the Onondaga Nation—suggests the conflicting desire to both acknowledge historical injustice and protect symbols of injustice. This contradiction belies national attitudes concerning representations of controversial figures in the United States whose supporters defend them based on two purportedly neutral themes: history and heritage. Architecture historian Dell Upton describes this phenomenon as the “dual-heritage ideology,” the belief that heritage is immune to criticism since it predates contemporary values and, therefore, “celebrants of each heritage should refrain from criticizing, expatiating upon, or even directly acknowledging the other.”5 According to this logic, the heritages of Italian Americans and Indigenous groups are part of parallel but separate histories, and neither group should question the historical figures upheld by the other. Upton’s dual-heritage ideology explains the strange phenomenon that occurred in Syracuse: “diversity” became a buzzword for the people who protested the Columbus Monument as well as for those who defended it.

Syracuse citizens on both sides of the debate agreed on the importance of cultural diversity but had antithetical ideas about its implementation in public space. When the CMC lawn signs cropped up in Syracuse neighborhoods, Columbus’s detractors produced their own on purple cardboard: “Celebrate Diversity: Remove Columbus” (fig. 4). The purple borrowed from the Haudenosaunee flag, which depicts a wampum belt symbolizing the unity of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca people. The monument’s protestors and defenders both invoked “diversity” as a value grounded in equitable representation despite their conflicting understanding of Columbus and the legacy of European contact.

In Syracuse, the Columbus Monument set in motion disputes concerning “diversity rights,” a legal term that denotes the recognition and respect of cultural heritage and commitment to nondiscrimination. Here I examine the built environment’s role in diversity-rights disputes, paying careful attention to the important but subtle ways that a controversial monument transformed a grievance into a public dispute. Significantly, although minority groups often experience violations of their diversity rights, these harmful experiences rarely become formal disputes put forward by publics who collectively name their grievances.6 Indeed, scholars of critical legal studies argue that “only a small fraction of injurious experiences ever mature into disputes,” since people often fail to articulate grievances either because they do not perceive them as especially harmful or because they doubt claims for redress will succeed.7 The debate over the Columbus statue played a critical role in transforming an unarticulated grievance into a public dispute, since the bronze monument is a physical marker that gives shape to colonialist attitudes and solicits recognition as an instrument of harm.

The conflict in Syracuse, which began back in 1992, was catalyzed by changes in public attitudes toward monuments following the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020. This uprising resulted in the removal of some Confederate monuments across the United States and emboldened Columbus protestors in Syracuse to believe that similar barriers inhibiting claims for redress might be toppled there. During the last two years, the Columbus Monument has provided a platform for protestors to articulate diversity rights, since the statue, like monuments to the Confederacy in the South, materialized historical events marked by racial oppression.

In order to understand how diversity rights emerge in public space, I look to critical legal studies, which identifies a three-step process by which people transform injurious experiences into disputes: naming, blaming, and claiming.8 In the case of the Syracuse Columbus Monument, Indigenous protestors first “named” the Columbus myth when they protested the statue’s right to occupy public space during the quincentennial celebration of the explorer’s travels in 1992. Protestors “blamed” the municipal government and State Parks Department, which dismissed Indigenous objections to a monument that commemorates the Spanish conquest of the “New World” and represents racial oppression.9 Indigenous protestors “claimed” that the Columbus Monument violated their cultural heritage when they demanded that city government remove the statue’s offensive text and surrounding images in the early 1990s.

In contrast, members of Syracuse’s Italian-American community responded by asserting their own right to respectfully represent their heritage in public space.10 Theorist of critical legal studies Robert Gordon has described this phenomenon as an assertion of “counterrights,” the process by which a disadvantaged group claims a right and the opposing party asserts a counterright in defense of their own interests (such as when 1960s feminists claimed abortion rights and conservatives responded by asserting the right to life).11 Gordon’s description of counterrights provides a broader context for Upton’s dual-heritage ideology. People have defended Confederate and Columbus monuments on the basis of dual heritage, which is symptomatic of the rights doubletalk that has shaped public discourse in American counterrights movements.

Monuments are not inert objects but take place in the built environment by creating culturally demarcated zones in which public space, national histories, and legal rights are mutually constituted. Because very few grievances ever develop into disputes, the Syracuse Columbus is a critical example of the ways monuments participate in the identification of grievances, the attribution of grievances, and the transformation of grievances into disputes.12 In the last two years, protestors and city governments have removed over three dozen Columbus statues in American cities.13 The multiple registers of signification for the Syracuse Columbus Monument—as art, as heritage, and as colonial symbol—set in motion conflicting interpretations of diversity that confused public debate, since both sides imagined themselves as warriors in the struggle against cultural homogeneity and ethnic oppression.

The Columbus Monument Boom

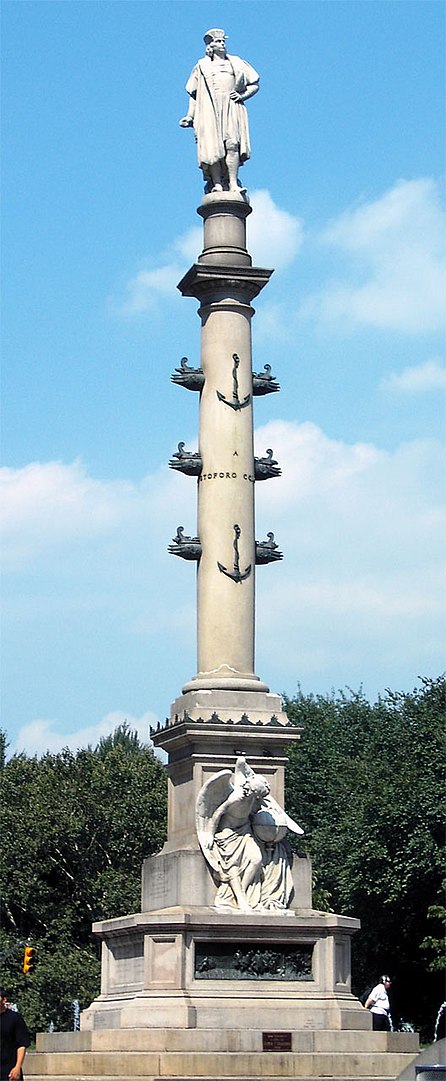

The 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago celebrated the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World and inspired the dedication of monuments to the explorer across the country.14 That same year, Italian Americans erected a marble statue of Columbus atop a seventy-foot base at the intersection of Eighth Avenue, Central Park South, and Fifty-Ninth Street in New York City (fig. 5). The Italian sculptor Gaetano Russo (1847–1908) projected bronze prows from the statue’s granite column, symbolizing the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. At the base of the monument, he installed a marble angel hunched over a globe, a reference to the false claim that Columbus’s detractors believed the earth was flat prior to his successful voyage. An inscription on the statue’s base recounts the explorer’s hardships:

To Christopher Columbus,

The Italian Resident In America,

Scoffed At Before,

During the Voyage, Menaced,

After It, Chained,

As Generous As Oppressed,

To The World He Gave a World.

The inscription situates Columbus as a “founding father” of the Italian American community and extols his new role in American mythology as an ethnic Italian hero.

In the nineteenth century, Columbus became a symbol of national heritage and pride. The mythologization of the explorer began one century earlier, when his origin story became a means for Americans to distance themselves from British patrimony after the American Revolution.15 During this period, descriptions of Columbus associated the explorer’s personal attributes—especially his courage—with a new American identity. Washington Irving solidified the explorer’s role as a national hero with the publication of his book A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828), which portrayed the noble explorer as a bridge between the old and new worlds.16

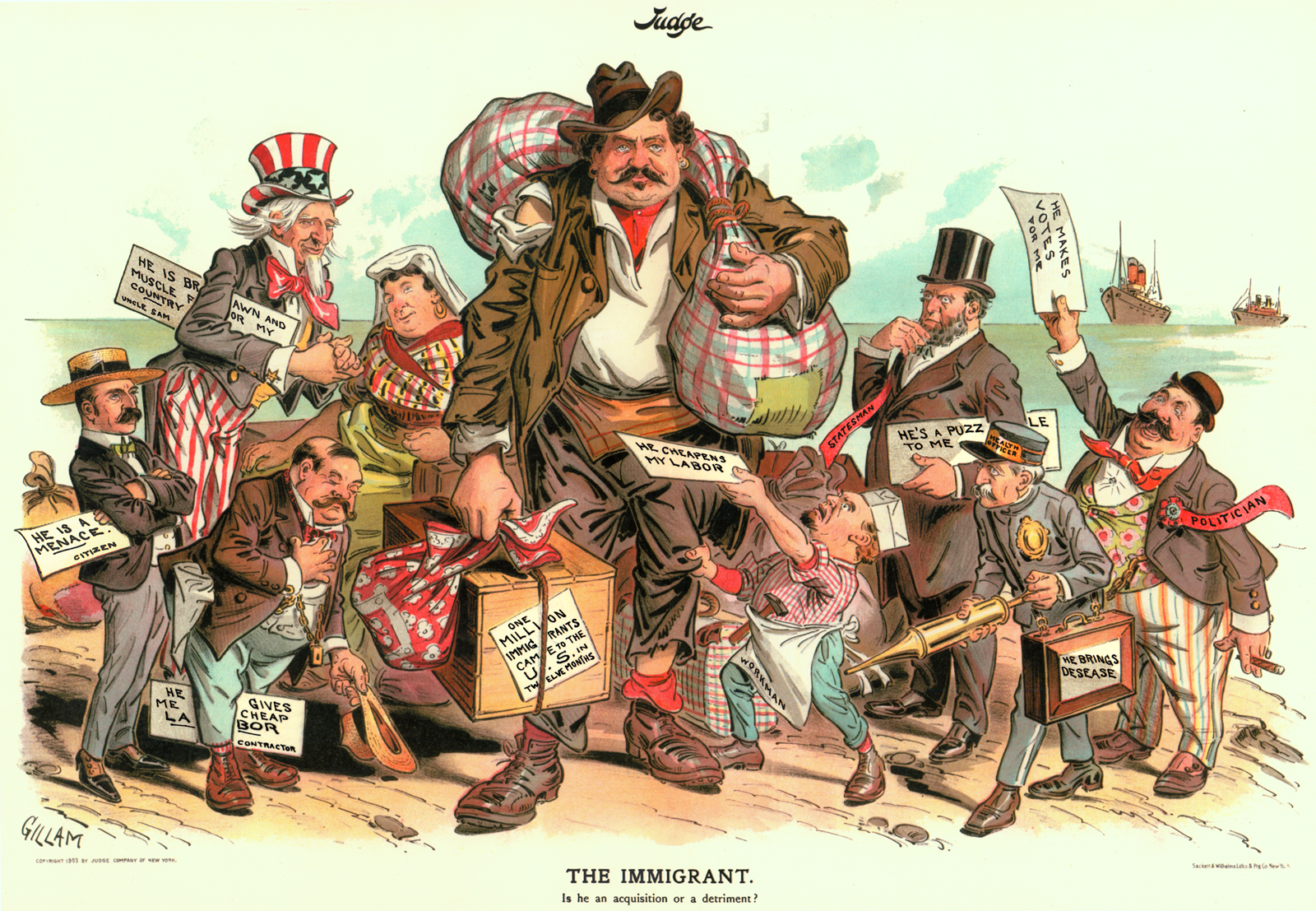

Revisionist accounts of Columbus’s voyage paralleled the rise of Italian immigration to the United States during the Progressive era.17 Four million immigrants from southern Italy immigrated to America between 1880 and 1924, and their settlement roused nativist and anti-Catholic attitudes that found their way into revisionist Columbian histories, which unearthed previously overlooked truths about the explorer’s journey but also besmirched Columbus as an example of Italian stereotypes. The historians Aaron Goodrich and Justin Winsor troubled the heroic Columbian origin story by involving the Caribbean slave trade and criticizing the explorer’s mistaken belief that he had reached India when he landed in the Bahamas.18 Columbus monuments countered these revisionist histories by commemorating the explorer in public space as a brave and essential figure to American history.19 The monuments’ placement in traffic circles, public parks, and plazas buttressed the original version of the Columbus myth as espoused by Irving and reinforced the historical figure’s connection with Italian Americans.

The Syracuse Monument

Syracuse University art professor Torquato de Felice first proposed erecting a monument to Columbus after returning from a trip to Florence in 1910.20 He brought home a miniature bronze model of Columbus designed by Florentine sculptor Vittorio Renzo Baldi, and he presented it to prominent members of the Italian American community in the hope of inspiring their interest in financing a full-size statue. The aforementioned rise in monuments to the explorer across the United States following the Columbian Exposition found fertile ground especially in New York, due to the state’s large Italian American population. The monuments ranged in size and splendor from the grand memorial in Manhattan’s Columbus Circle to the modest bust installed in the Belmont neighborhood of the Bronx. De Felice’s proposal for a Syracuse Columbus statue occurred shortly after the state of New York declared Columbus Day a holiday on October 12, 1909. The ensuing Columbus Day celebrations in New York City united the diverse inhabitants of Little Italy, who had segregated themselves into blocks that corresponded to Italian provinces.21 In a similar way, the proposed Columbus Monument in Syracuse promised to bring together the diverse Italian immigrants who first arrived in the city several decades earlier as laborers for the West Shore Railroad.

Early Columbus Day festivities forged an Italian national identity for participants, sometimes at the expense of regional Italian traditions. Pan-ethnic Italian American benevolence societies sponsored these annual events and financed the construction of Columbian monuments. As historian Peter G. Vellon shows, the Italian Americans at the forefront of these Columbus Day festivities were wealthy immigrants who “supported an upper-class notion of Italian national identity . . . based upon an imagined ‘Italian’ heritage of civilization and whiteness.”22 Consequently, upper-class Italian Americans discouraged certain regional traditions and dialects (especially from southern Italy) in favor of promoting a pan-Italian identity, which Columbus monuments and annual festivities made tangible for working-class immigrants as well as for themselves.

The prominent Italian Americans in Syracuse solicited local and international support in financing the Columbus Monument. The Federation of Italian Societies donated twelve hundred dollars to the newly established Columbus Monument Corporation (CMC) in Syracuse in 1928.23 Fundraising efforts for the Syracuse statue were slow, since World War I had interrupted the monument campaign. But the CMC raised nearly eighteen thousand dollars by the end of the decade, largely owing to wealthy members of Syracuse’s Italian society, such as clothing manufacturer Joseph Pietrafesa, who served as the CMC’s president.24 When Syracusans struggled to finance the shipment of granite and bronze from Italy, Benito Mussolini agreed to pay their remaining balance.25 In these ways, Pietrafesa harnessed the financial capital of ethnic societies in New York, local Italian Americans, and even a foreign dictator to fund the city’s statue. The Pietrafesa family played an outsized role in maintaining the Columbus Monument in Syracuse for nearly a century.

In the 1930s, Syracuse Mayor Rolland Marvin offered crucial support for the monument. When Italian Americans proposed St. Mary’s Circle as the desired location, Marvin approved their plan on the condition that a well-known architect design the project.26 When the local architect Dwight James Baum (1886–1939) agreed, Marvin offered his enthusiastic approval for the proposed site.27

Baum was an established and successful architect when he began work on the Syracuse Columbus. He had graduated from Syracuse University’s School of Architecture in 1909 and then moved to Florida to design a number of prominent civic buildings and houses during the state’s land boom in the 1920s.28 Baum garnered attention for his houses, which demonstrated his mastery of the Mediterranean, English, Georgian, and Colonial styles. When the Depression dried up real estate opportunities in Florida, Baum returned to Syracuse, where he designed a number of buildings for his alma mater, including the College of Medicine, the Maxwell School of Citizenship, and Hendricks Chapel, a grand Palladian building that terminated the university quadrangle. Like many Depression-era architects, Baum sought commissions for public works from local and national governments in the 1930s. During this lean time, the Italian American community approached Baum about designing a sculpture in honor of their ethnic hero.

The Columbus Monument provided an opportunity for Catholicism to play a role in the national origin story since Italian Americans celebrated the explorer for his faith. St. Mary’s Circle thus offered a logical location for the Columbus Monument in Syracuse. The statue would stand in front of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and alongside two Beaux-Arts buildings (Carnegie Library and the Onondaga Courthouse) abutting the circle, which would offer a grand neoclassical context for the monument (see figs. 1 and 6). Nativist attitudes intensified in the nineteenth century in response to mass migration to the United States, and immigrants from Catholic countries were treated with special hostility, since some citizens viewed them as a threat to the Protestant values upon which the country was founded.29 Discrimination toward Catholics led some of the faithful to establish antidefamation organizations in the late nineteenth century, most famously the Knights of Columbus.30 The Knights used Columbus Day ceremonies to emphasize the explorer’s faith and thereby assert the importance of Catholicism to the United States’ origin. The Post Standard in Syracuse reinforced the Catholic message in an article that described the city’s new statue: “[Columbus] faces the west and the cathedral, depicting his coming from a Catholic people.”31 The Knights sponsored radio programs in which they described Columbus’s heroic personal qualities—morality, fortitude, faith, and self-discipline—as attributes aligned with Catholicism and good American citizenship. Columbus as a Catholic icon became entwined with his persona for Italian Americans. Indeed, in 2021—nearly one hundred years after the Columbus Monument’s inauguration ceremony—Syracusans still emphasized the explorer’s moral virtues and faith in their holiday speeches. “Hear the prayers of our people to celebrate our great ancestor of courage, tenacity, and faith,” exhorted Bishop Douglas Lucia to the crowd gathered for the annual wreath-laying ceremony on October 11, 2021.

The Monument’s Iconography

The Syracuse monument’s iconographic program illustrates scenes from Irving’s nineteenth-century narrative—A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus—the source that was foundational to establishing Columbus’s role in American mythology and that provided rich visual descriptions of the explorer’s heroic arrival in the Caribbean and his relations with Indigenous communities.32 The Syracuse monument depicts favorable episodes in the Columbus story that came under fire in the late twentieth century as revisionist historians recovered the histories of colonization and genocide at the heart of the Columbus myth.

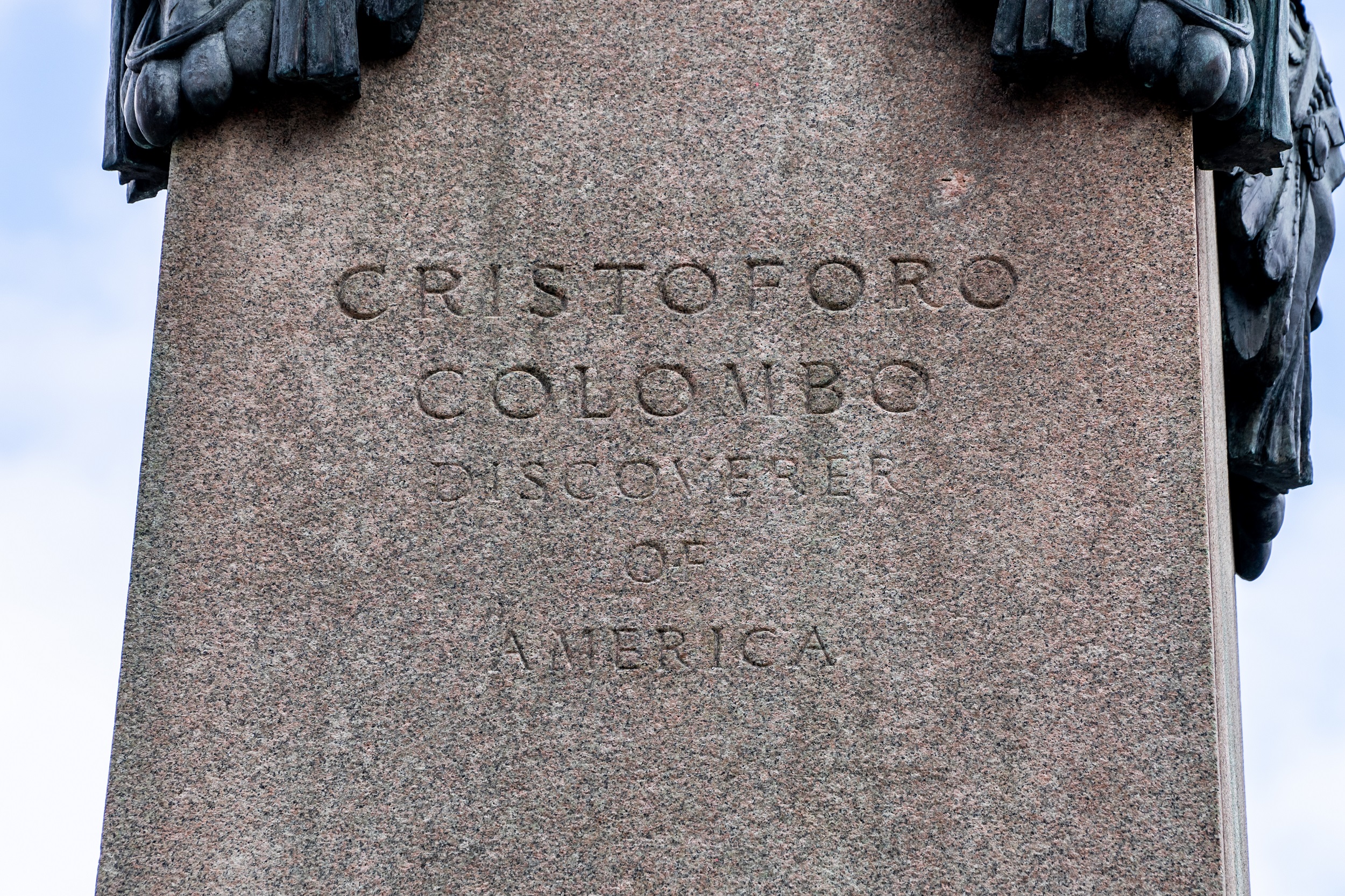

The Columbus Monument in Syracuse recalls earlier effigies of the explorer but also departs from representational conventions in several ways. Baum almost certainly responded to Russo’s famous Columbus statue, which similarly positioned the admiral high atop a neoclassical column with a square pedestal, projecting ship’s prows, and figures adorning the plinth and base. Since the mid-nineteenth century, Columbus sculptures had often included nautical features that referenced the explorer’s travels. Baum situated the monument in a pool in which he placed colored pebbles in the shape of a compass. In the center of the pool, he erected a granite shaft upon which a twelve-foot-high Columbus stood thirty feet above the ground. Baum projected a single ship from the granite plinth beneath his monument’s square pedestal (fig. 7). The monument portrays Columbus as a young man, a neoclassical figure standing in contrapposto and dressed in the manner of a fifteenth-century nobleman, wearing a cloak, brimmed hat, doublet, tights, and soft shoes (fig. 8). In his left hand, the admiral grasps a chart (a typical accessory), while his empty right hand gestures outward. The monument’s multiple nautical features illustrate the text on the statue’s plinth: “Discoverer of America.”

Conspicuously, Baum did not integrate a globe into his design for the Columbus statue, despite its popularity as a motif. Artists frequently included the globe in depictions of Columbus: sometimes an allegorical figure holds the globe; often a globe stands beneath the explorer’s right hand; giant globes function as pedestals beneath Columbus’s feet; and, rarely, the globe replaces Columbus altogether, as in the Plaza Independencia in Durazno, Uruguay (fig. 9). Irving originated the famous story that Columbus proved that the Earth was round and, in doing so, glorified Columbus as a protomodern figure guided by science and reason. Victorian historians later debunked the flat-earth myth by pointing out that ancient Greek mathematicians had known the world was round thousands of years earlier. While Baum did not explain why he did not include a globe, it is likely that he was responding to the growing awareness of this tale’s fallacy.

The most troubling feature of the Syracuse Columbus are the four heads of generic Native Americans installed beneath the admiral’s feet at the top of the granite column (fig. 10). The disembodied heads bear feathered headdresses, or war bonnets, typical of American Plains Indians, a costume worn neither by the Lucayos, whom Columbus encountered in the Bahamas, nor by the local Onondaga people of Central New York. The explorer’s role as a national hero required Americans to overlook the fact that he had landed in the Bahamas as opposed to mainland North America. By incorporating Plains Indians, the Syracuse Monument further confuses the facts of the 1492 landing but manages to reinforce Columbus’s reputation as a national figure, despite his waning influence in the twenty-first century.

Baum’s decision to render the bronze figures with war bonnets reflected a deeper trend in which US artists represented all Indigenous peoples as Plains Indians, a problem partially owed to the fame of George Catlin’s 1830s paintings of tribes in the Midwest.33 During the nineteenth century, Catlin’s paintings inspired the depiction of Indigenous peoples in illustrated books, dime novels, and Wild West shows.34 W. Richard West, former director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and himself a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, has described Catlin’s traveling exhibition, the famous “Indian Gallery,” as a tool for exploiting and commodifying Indigenous cultures. West wrote that Catlin was a complex historical figure whose empathy toward the subjects of his paintings was compromised by the “invasive undertone” that guided his “obsession with depicting [Plains] Indians.”35

Earlier Columbus monuments do not offer a direct iconographic precedent for the disembodied heads that Baum attached to his Syracuse sculpture. Several indirect precedents, however, can be found in William Elroy Curtis’s Christopher Columbus: His Portraits and His Monuments, an exhaustive catalogue published on the occasion of the Columbian Exposition in 1893.36 Baum almost certainly consulted this well-known book when devising his Syracuse monument. He explained that the heads beneath the admiral’s feet “expressed the new America that Columbus discovered.”37 Artists sometimes portrayed an Indigenous woman—personifying America—beneath a standing Columbus. Italian artist Lorenzo Bartolini depicted America as a young bare-chested woman holding a crucifix and kneeling before a standing Columbus in Piazza Acquaverde, a public square in the explorer’s birthplace of Genoa (fig. 11).38 Bartolini placed Columbus’s left hand on an anchor and extended his right hand toward the maiden, their hierarchical relationship reinforced not only by their postures but also by the way the artist bent the woman’s neck in order to accommodate Columbus’s hand, which grazes her bare shoulder and charges the scene with a disturbing sense of violence and eroticism (fig. 12). Curtis described Bartolini’s work as “the finest existing monument to Columbus” and devoted two full pages to its description.39 He illustrated similar monuments that also depict a sitting or crouching Indigenous woman beside an upright Columbus, including examples in Washington, DC; Lima, Peru; Colón, Panama; Ligornetto, Switzerland; and Cartagena, Colombia. These monuments materialize the encounter between Spain and the New World by reducing it to two bodies whose relationship suggests a familiar scene: the eroticized subordination of women.

Artists did not usually represent America as a male figure. The conventions of neoclassical sculpture dictated that women represent abstractions, such as virtues and nations, so it was peculiar that Baum used four disembodied male heads to symbolize the territory that would become the United States. To my knowledge, only one artist had depicted America as a male figure in the long history of Columbus monuments that preceded Baum’s 1934 statue. On the Columbus Fountain, built at Union Station in Washington, DC, in 1912, Lorado Taft designed a standing Columbus beside a crouching Indigenous man, who reaches to pull an arrow from the quiver on his back. The statue’s text honors Columbus as the “Admiral of the Ocean Seas and the Discoverer of the New World,” ignoring the Indigenous groups who occupied the territory that would later become the United States.

Since the early 1990s, Baum’s choice to symbolize America through the bronze heads of abstracted Plains Indian warriors has received criticism for its inauthentic and cruel depiction of Indigeneity. By installing the heads below Columbus’s feet, Baum echoed the strict visual hierarchy that expresses the dominant explorer and the subordinate Native person in many other examples from the last century of monument production.

In addition, Baum’s monument includes four bas-relief panels that represent notable events from Columbus’s life. The first chronological panel represents Columbus’s arrival at the Court of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain to request financial support for his trip to the Indies (fig. 13). The next depicts Columbus’s ships mid-voyage on the open sea (fig. 14). The third panel shows Columbus’s arrival in the tropics, a well-established subject in Columbus iconography (fig. 15). Baum pictured a soldier raising the Spanish flag, and he positioned colonizers behind the flag and Indigenous people in front of it. His relief bears a striking resemblance to Bartolini’s depiction of the same event for his Columbian monument in Genoa. The final scene shows Columbus’s triumphant return to the Spanish court, where the explorer presents captured Indigenous peoples whom he intends to sell into slavery (fig. 16).40

Artists rarely depicted this postconquest scene in the life of Columbus. Here, Columbus greets the enthroned royal pair with gifts from his trip to the Caribbean. Approaching the throne, Columbus gestures toward two soldiers carrying sacks—presumably filled with gold—and two crouching Indigenous warriors wearing Plains Indian headdresses. Soldiers and courtiers witness the event, including a seated woman in the foreground whose attention is fixed on the crouching, bare-chested Indigenous men. The nakedness of the Indigenous figures contrasts with the richly dressed Spanish nobles, suggesting that nakedness functions to indicate a lack of decorum, civility, and humanity, as does the Native people’s kneeling posture among the standing onlookers.

Few iconographic precedents account for this final frieze in the Spanish Court, but references to violence perpetrated by the Lucayo people and the slavery subsequently imposed on them mark several Columbus monuments built in the nineteenth century. An example appears on the Columbus Doors designed by Randolph Rogers (1825–1892) for the eastern entrance to the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC, in 1863 (fig. 17).41 The eight panels on the doors illustrate key scenes in the explorer’s life: Columbus before the council of Salamanca, his departure from the convent of La Rábida, Columbus’s audience at the court of Ferdinand and Isabella, his departure from Palos, his first encounter with Indigenous people, his return to Barcelona, Columbus in chains, and, finally, his death.42 The inspiration for these scenes came from Irving’s influential histories of Columbus, especially his description of the “discovery” of San Salvador, which inspired reliefs on several Columbian monuments: “Columbus then rising drew his sword, displayed the royal standard, and assembling round him the two captains . . . he took solemn possession in the name of the Castilian sovereigns, giving the island the name of San Salvador.”43 Irving wrote that the native Lucayo people, who had hidden in the forest upon the ships’ landing, gradually emerged to witness the “ceremonies of taking possession.”44

Rogers depicted a later moment in this iconic scene on the top of the right door: while the Spanish flag flies in the distance, Columbus and his crew look disapprovingly on a sailor who has captured a young Indigenous woman (fig. 18). The sailor is half clothed, his bare chest a marker of savagery but also an opportunity for Rogers to demonstrate his skill in rendering musculature in an expressive pose that recalls Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s well-known Rape of Proserpina (1621–22; Borghese Gallery and Museum). The Lucayos stand nearby, witnessing the event from behind forest trees. By including this scene of Indigenous kidnapping and impending rape in the moments following Columbus’s heroic landing in the New World, Rogers communicates the explorer’s own moral integrity by contrasting his deeds with those of his greedy and unscrupulous men. Rogers accomplishes this by conflating two episodes in Irving’s history. In his account of Columbus landing in San Salvador, Irving wrote that among the Lucayos “there was but one female . . . , quite young, naked like her companions, and beautifully formed.”45 While he did not describe a kidnapping in San Salvador, he wrote that several months later, a sailor captured a young female inhabitant of Hispaniola only to be chastised by Columbus, who forced him to return her. Irving praised Columbus for insisting on the Indigenous woman’s return to her husband along with “magnificent presents,” interpreting it as a testament to the admiral’s moral character.46 In his frieze, Rogers combines the two episodes in Irving’s history—Columbus’s arrival in San Salvador and his crewman’s kidnapping in Hispaniola—to exalt the explorer’s navigational skills and blameless character.

A few artists depicted Columbus’s return to the Spanish Court in Barcelona, where he was accompanied by Indigenous captives. Rafael Atché pioneered the earliest depiction of this scene for one of his eight bronze relief panels installed on the octagonal plinth of the Barcelona Columbus in 1888. Atché shows Columbus kneeling before Queen Isabella in a reunion similar to the one described by Irving: “As Columbus approached the sovereigns rose, as if receiving a person of the highest rank. Bending his knees, he [Columbus] offered to kiss their hands.”47 Behind the kneeling Columbus, Atché illustrates the admiral’s crew and two Indigenous figures: a father and either a child or a young woman. Irving writes that Columbus took six Indigenous people back to Barcelona, but artists had trouble squeezing so many figures—captives, royalty, courtiers, sailors, and Columbus—into their relief panels, so they often reduced the number of Indigenous captives.48 Baum surely looked to these iconographic precedents when designing his own representation of the encounter between Indigenous figures and the court in Barcelona.

Baum’s depiction of Queen Isabella’s Court follows Irving’s description of the historic event (fig. 16): “To receive him [Columbus] with suitable pomp and distinction, the sovereigns had ordered their throne to be placed in public under a rich canopy of brocade of gold, in a vast and splendid saloon.”49 In the Syracuse frieze, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella sit underneath a canopy, where they receive Columbus, his sailors, and two captured Indigenous people. In the background a faint outline of rooftops and columns indicates the outdoor setting. A number of courtiers witness the event, most likely the nobility of Castile, Valentia, Catalonia, and Aragon—all historical figures that Irving places at the scene. The twin themes of colonialism and racial oppression that characterize this scene would later incite criticism from protestors of the Syracuse monument.

Protesting Columbus: The 1992 Quincentennial Celebration and Summer 2020

The first significant protests of the Columbus Monument occurred in 1992 and were directed at the iconography of the sculpture, the bas-reliefs, and the inscription celebrating Columbus’s colonialist ambitions. As I will discuss, despite public criticism at the time, the Syracuse city government refused to alter the statue, since they claimed that any change would compromise the historical integrity of the monument. Anger about the monument reawakened in the summer of 2020, following the wave of protests against diversity-rights violations that were inspired by the murder of George Floyd and the widening Black Lives Matter movement.

In the years leading up to the 1992 quincentennial celebration of Columbus’s journey to the “New World,” the Syracuse municipal government planned to restore its downtown monument with the goal of completing the project by Columbus Day 1992.50 The CMA financed the improvements (estimated to cost $450,000) with the help of a $200,000 historic preservation grant from the state. The group decided on the following improvements: shining and restoring the bronze, cleaning and reinforcing the stone, repairing the fountain, adding benches, and, most importantly, returning the four bronze heads of Native Americans to their original position beneath Columbus’s feet. Curiously, the heads had gone missing decades earlier. Shortly after the unveiling of the Columbus Monument, Syracusans discovered that the bronze heads stained the granite pillar upon which they were fixed.51 Parks Department officials unbolted the heads from the statue and placed them in storage, where they remained for fifty years until two local men stole and sold them at auction in Atlanta, Georgia. Syracuse officials tracked the heads to an Orlando business owner, who had purchased them with the intention of displaying them above his restaurant. In 1989, Syracuse newspapers announced that the recovered heads would be a prominent feature of the restored Columbus Monument.52

The quincentennial anniversary of Columbus’s journey in 1992 sparked global debates in which protesters criticized particular features of the Columbus story as well as the monuments that represented it. Historians first deflated Irving’s mythical Columbus during the Progressive era, when Goodrich and Winsor “recast Columbus as a slave trader and blunderer” in their popular histories.53 In the final decade of the twentieth century, critics of Columbus amplified their message as anticolonialist themes became more widespread. Accounts were written that blended nonfiction, humor, and fantasy to appropriate the Columbian story and retell it from the perspective(s) of Indigenous peoples.54 In his book Lies My Teacher Told Me About Christopher Columbus: What Your History Books Got Wrong, James W. Loewen investigated a number of popular textbooks of American history to debunk well-known but unproven episodes in the Columbus story.55 Protests at the time of the quincentennial focused on retelling the narrative with an eye toward acknowledging and examining the explorer’s role in Spanish colonialism. Protestors identified Columbus monuments as instruments of oppression, since they perpetuate the glorification of Columbus by illustrating outdated hagiographic scenes described in Irving’s classic history.

In 1991 several Mohawk activists organized protests in Syracuse demanding the removal of components of the Columbian statue. For example, Tom Sullivan criticized the city’s plans to reattach the bronze heads of Native Americans, claiming that they communicated servitude.56 He picketed the quincentennial events and organized a “Truth in Peoples’ History” committee to debunk the Columbus myth.57 The inscription at the base of the Columbian plinth, “Discoverer of America” (fig. 19), drew criticism from Mohawk activist and schoolteacher Romaine Mitchell, who noted, “Columbus was lost. He didn’t discover anything . . . there were already people here when he arrived.”58 Most important, protesters demanded the removal of the frieze depicting Indigenous captives kneeling before Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand as the inaugural instance of the transatlantic slave trade. In light of the new revisionist histories of atrocities resulting from Columbus’s voyage, the protestors demanded that the city alter the statue to better reflect an accurate account of the past.59

On October 13, 1991, some protestors painted the frieze red in an act of “symbolic vandalism,” a term coined by art historian Erika Doss to describe ways that people alter and damage public art as a form of dissent.60 Acts of symbolic vandalism have been used to undermine heroic portrayals of Columbus in cities across the United States. A recent example of symbolic vandalism is The Cloaking of the Statue of Christopher Columbus behind the Bayfront Park Ampitheatre, Miami, Florida (December 2019–January 2020), in which Dominican-American artist Joiri Minaya enrobed the Bayfront Columbus in floral spandex depicting local plants like rompe saraguey, an herb used by Indigenous groups for spiritual cleansing. Minaya’s symbolic vandalism invited viewers to reconsider the statue and reflect on the question of cleansing and rectifying Columbus’s troubled history.61 In June 2020, protestors in Richmond, Virginia, used ropes to topple a statue of Columbus that had been installed in Byrd Park since 1927.62 They then dragged the statue two hundred yards and sunk it in a nearby lake. In these ways, symbolic vandalism is symptomatic of the naming, blaming, and claiming process whereby protestors collectively identify a grievance and then use vandalism as a means to claim diversity rights in public space.

The original wave of protests in Syracuse caught the attention of the State Parks Department, which briefly considered removing the monument’s contested frieze during the summer of 1991. The deputy commissioner of State Parks, Julia Stokes, however, had already promised $200,000 to the Syracuse monument’s restoration before Sullivan’s protests took place in Columbus Circle. “Balancing cultural sensitivity and architectural accuracy is the kind of issue that causes preservation advocates to agonize,” lamented Stokes.63 Although Stokes defended the frieze on the basis of historical fact—it accurately depicts Columbus’s presentation of Indigenous captives to the Spanish queen and king—she conceded that the scene did not merit celebration during the quincentennial. Members of the Italian American community argued that the famous explorer’s story should not be judged by contemporary standards and that any modification to the statue compromised its historical accuracy.64 These arguments failed to acknowledge that the statue itself includes grave historical inaccuracies, since it depicts the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean in the dress of Plains Indians. The State Parks Department ultimately decided to restore the statue without any alterations, a decision that reflected their fidelity to “integrity,” a guiding principle for preservationists that dictated the selection and preservation of public monuments and buildings in the 1990s.65 The question of social justice was not a formally recognized criterion in the preservation discipline at the time.

There was a shift in the tenor of the protests around the Syracuse Columbus Monument three decades later, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020. The history of anti-Columbus protests in Syracuse reflects the increasing awareness—both local and global—that Columbus Day celebrations perpetuate colonialist attitudes and dismiss the genocide of Indigenous people. These same concerns motivated the Syracuse protestors who gathered in Columbus Circle in 1992 and in 2020, but public tolerance for the commemoration of troubling historical figures had lessened considerably after the Black Lives Matter movement became strong. Whereas protesters in the 1990s appealed to city government to alter parts of the statue, those of a later generation demanded the removal of the monument entirely.66 The Black Lives Matter movement, which draws attention to racial violence in public space, spurred demands for the removal of monuments dedicated to historical figures associated with slavery and colonialism. While dissatisfaction with the sculpture was not new, the explosive arguments on both sides of the debate were a recent phenomenon that I attribute to the newly widespread awareness of diversity rights brought about by the movement.

Italian American Responses

The art historian Kirk Savage rightly argues that monuments are the most conservative artworks since they neatly package one particular interpretation of a historical figure or event for all time.67 But monuments are only conservative if we passively accept them as part of the built environment. The removal of Confederate monuments in the United States has attracted international media coverage, but journalists have paid less attention to the simultaneous public outcry against Columbus monuments.68 Confederate and Columbus monuments both offer a stage for participants in Black Lives Matter protests and Indigenous Peoples’ Day rallies to collectively identify narratives of racial oppression that assume physical form in the effigies of Confederate soldiers and Columbus figures.69

During the Indigenous Peoples’ Day protest I attended in 2021, a young woman whom I could barely discern in the evening light declared to the crowd, “We gather to mourn the violence of Columbus and those that came after him, actions rooted in white supremacy.” I leaned against the cold limestone walls of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and squinted to see a man who yelled, “Fuck you! . . . You’ll lose!” as he darted between Jefferson and Montgomery Streets. Standing in front of me, a few college students started gesturing at a heavily tattooed young man wearing a baseball cap over his shaved blonde stubble. “He’s a Nazi if I’ve ever seen one, so keep an eye on him,” whispered a young woman to her friends as she edged closer to the growing crowd. These same fears of Nazism and white supremacy characterized events held to remove Confederate monuments after 2020.

Italian Americans have long bristled at the suggestion that Columbus might be associated with white supremacy, arguing instead that the explorer was a symbol of pride for all immigrants, and that the Klu Klux Klan (KKK) historically fought against the Italian community’s right to erect ethnic statues in public space. For example, when the Italian Americans in Richmond, Virginia, tried and failed to erect a Columbus monument in 1925, the KKK celebrated, since they perceived Italian identity and Catholicism as threats to the Anglo-Saxon Protestant hegemony.70 The KKK stoked Protestant fears around the mass migration of Catholic Italians to the United States by demonizing the Spanish conquerors who “committed atrocities” and praising the “saintly Pilgrims.”71 In the twentieth century, the early history of the United States was a battleground, and different ethnic and religious groups fought for their rightful place in the national origin story. For Italian Americans, the Columbus story offered a ticket to cultural inclusion and provisional white status.72

In Syracuse, the Italian American Pietrafesa family had long supported the Columbus Monument, raising the funds to erect it in 1934 and later defending the statue against material and ideological attacks. When Indigenous protestors threw red paint on the statue in 1991, Richard Pietrafesa criticized those involved for damaging the statue, pointing out that local tribes had attended the monument’s unveiling ceremony in 1934.73 Three decades later, when Mayor Walsh called for the monument’s removal, the Pietrafesa family, still associated with the CMC, launched a crusade to protect Columbus Circle. Anthony Pietrafesa served as the lawyer of the CMC, which successfully sued the city of Syracuse to reverse Mayor Walsh’s decision.74 On March 15, 2022, State Supreme Court Judge Gerard Neri ruled that Mayor Walsh did not have the authority to remove the statue, a verdict that discouraged Syracuse protestors and complicated efforts elsewhere to remove Columbus statues in the state of New York. The legislative battle waged by New York State lawmakers over the Syracuse Columbus demonstrated the limited power of mayors to remove municipal monuments and overlooked the historical importance of city officials in the creation and maintenance of public art.

Some Italian Americans in Syracuse, however, opposed the Columbus statue on the grounds that it perpetuated a “false myth.” The newly formed Women of Syracuse and Italian Heritage gathered on the evening of Indigenous People’s Day 2021 in solidarity with the anti-Columbus protestors. “We’re obligated to honor historical truths, not false myths . . . this monument does not represent my heritage,” preached Natalie LoRusso, a third-generation Italian American living in Syracuse. “We request the removal of this false idol based on genocide,” LoRusso added. The “false myth” concerned Columbus’s role as an ethnic hero for Italian Americans, who had perpetuated a story of his heroism and moral virtue with little regard for his participation in a colonialist system that perpetrated the genocide of Indigenous peoples. Instead, LoRusso supported Mayor Walsh’s plan for Heritage Park, where the city would erect multiple statues dedicated to famous ethnic figures. Several speakers suggested the city replace Columbus with the statue of another prominent Italian American but did not indicate any particular historical figure. The Women of Syracuse and Italian Heritage proved the Columbus Monument did not appeal to every Italian American, since the explorer’s story is impossible to reconcile with historical racial violence and its continued shaping of the present.

The Battle for Diversity Rights in Public Space

Since I arrived in Syracuse in 2020, I did not know to what extent pedestrians frequented Columbus Circle before the COVID-19 pandemic. In the time of quarantine and confusion about the disease, the area was little used. A few people ate their lunches on the benches that the CMC built for the quincentennial celebration. Rarely did people stop to smoke a cigarette beside the gargoyle fountain or bring their children to play in the open plaza. Much like the rest of downtown Syracuse, people abandoned Columbus Circle when the nearby offices adopted telecommuting and restaurants shuttered. Syracuse already had trouble retaining small businesses in their downtown district before the pandemic. Revitalization efforts did little to bring new jobs and foot traffic to downtown, despite over $650 million spent on redevelopment projects over the last decade.75 With the exception of the occasional dog walker, Columbus Circle was empty most days that I drove past it during the commute from Syracuse University to my apartment downtown.

Looking at the lonely Syracuse Columbus, we might question if the statue really matters, given the lack of pedestrian traffic at Jefferson and E. Montgomery Streets. We might ask ourselves, “Who is paying attention to the Columbus Monument anyway?” While it is tempting to think of monuments as inert objects in space, it is wise to remember that monuments are always soliciting our attention, even if that means occupying a faded place in our “cognitive maps” of the city.76 I argue that our encounters with monuments are most critical when we are not looking at them too closely but instead passively accepting them as objects that belong in our downtown plazas and median strips. Our passive acceptance of Columbus standing atop four disembodied Indigenous heads obstructs our recognition of the contested spaces in which monuments operate, wherein different groups in a multiracial society struggle for basic opportunities, such as jobs, housing, and education. Moreover, this passive acceptance is a privilege that is unevenly distributed in Syracuse, since the Columbus myth is not “neutral” for the citizens who insist that the statue regularly inflicts harm.

Richard Dyer has cautioned against the omnipresence of whiteness in film and media, which has naturalized white bodies as simply bodies bearing no marker of race.77 For Dyer, the power of whiteness is most insidious when it is not recognized at all, and white bodies are just considered normative bodies. Historically, for Italian Americans, the neoclassical bodies of Columbus statues helped effect their transition from a contested whiteness to a provisional whiteness during the twentieth century. The statue’s Greco-Roman features countered caricatured depictions of Italians as fat, poor, sloppy, mustached men, newly arrived on American shores in the 1920s (fig. 20). More important, Irving’s heroic account of the explorer’s travels offered a place in American history for Italian Americans eager to assimilate. It is important to note that some white ethnicities are more securely marked white than others, and many Italian Americans still feel the instability of their place within white society. However, as Dyer argues, I believe that examinations of “white ethnicity tend to lead away from a consideration of whiteness itself.”78 We must consider not just what Columbus means to Syracusans but how he manages to express this meaning via the recognition that his neoclassical statue—rendered in a style derived from the Euro-American obsession with whiteness in antiquity—has come to be associated with heroism and helps assert the statue’s purported neutrality as “history” and “heritage.”79

Upton has described dual heritage as a strategy for precluding value judgments.80 Adherents to the dual-heritage ideology consider heritage to be an “unquestionable value” and fail to acknowledge the uneven power relations that defined—and continue to define—a multiracial society. The concept of racial stratification is anathema to dual-heritage adherents, who dismiss historical injustices by arguing that we must not interpret past events according to contemporary values. Columbus defenders do not find it offensive to suggest that a monument dedicated to the explorer and another statue honoring the Onondaga people could occupy the same downtown Syracuse plaza. Furthermore, they claim that their disinterested perspective makes it possible to appreciate both heritages, failing to recognize disinterest itself as a marker of privilege.

Columbus defenders believe that nineteenth-century histories of the explorer should not be countered by contemporary ones. They do not recognize that history is a dynamic process in which scholars reinterpret past events according to new evidence as well as developments in related fields, such as political science and sociology. Monuments reinforce this erroneously static understanding of history, since statues capture a particular interpretation of a historical figure or event described at a specific historical moment and then calcify it in stone or bronze. The Columbus Monument in Syracuse perpetuates Irving’s classic tale despite the publication of new histories that challenged Irving’s heroic portrayal of the Genoese explorer over the ensuing century. As critical histories of Columbus found their way into cultural conversation, protestors disputed particular features of Columbian monuments: namely, the attribution of Columbus as the “discoverer” of America, and any illustration indicative of Indigenous slavery.

The CMC’s battle to “save” Columbus was waged in the New York State Supreme Court. Judge Neri ruled that Mayor Walsh did not have the legal authority to remove the Columbus Monument in March 2022. The CMC announced the legal victory on their website: “It’s time for everyone to come together and pursue the additive approach to Syracuse’s public art. Enough taxpayer money has been wasted.”81 I visited CMC’s website over the next few months, noting the group’s interest in using their legal victory to strategize with other Columbus monument defenders in the state of New York and elsewhere. The Supreme Court ruling established an important precedent in the struggle to remove Columbus monuments, and Indigenous people now face a major setback in their struggle for diversity rights in public space. Although tolerance for the symbols of racial injustice has diminished across the United States, as Confederate monuments are increasingly removed from public spaces, Columbus monuments like the Syracuse example continue to perpetuate troubling myths about our national origin. Such monuments sustain injurious racist and violent imagery in our cities while their defenders uphold them by invoking the power of heritage.

Cite this article: Kristina Borrman, “Naming, Blaming, and Claiming: The Columbus Monument and the Struggle for Diversity Rights in Syracuse, New York,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 2 (Fall 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.15172.

Notes

- Indigenous Peoples’ Day Rally, Columbus Circle, Syracuse, New York, October 11, 2021. ↵

- For more on the troubled history of Columbus, see James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me About Christopher Columbus: What Your History Books Got Wrong (New York: New Press, 1989). ↵

- “Solution,” Keep the Columbus Monument, accessed March 20, 2022, https://columbusmonumentsyracuse.com/?page_id=337. ↵

- Chris Baker, “Walsh to Remove Syracuse’s Columbus Statue, Rename Downtown Circle,” Syracuse.com, October 9, 2020, https://www.syracuse.com/news/2020/10/walsh-to-remove-columbus-statue-rename-downtown-circle.html. ↵

- Dell Upton, What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 17. ↵

- William L. F. Festiner, Richard L. Abel, and Austin Sarat, “The Emergence and Transformation of Disputes . . . Naming, Blaming, Claiming,” Law and Society Review 15, nos. 3/4 (1980/81): 635–36. ↵

- Festiner, Abel, and Sarat, “Emergence and Transformation of Disputes,” 636. ↵

- Festiner, Abel, and Sarat, “Emergence and Transformation of Disputes.” ↵

- Sean Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate: Indians Say Depiction of Bondage Stains Columbus Monument,” Post Standard, June 10, 1991, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse: Scrapbook and Newspaper Clippings, 1934–2010, Local History and Genealogy Department, Onondaga County Public Library, Syracuse, New York (hereinafter Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse). ↵

- Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate.” ↵

- Robert Gordon, “Some Critical Theories of Law and their Critics,” in The Politics of Law: A Progressive Critique, ed. David Kairys (New York: Basic, 1998), 657. While many scholars of critical legal studies question the efficacy of rights discourse because of counterrights claims, I agree with Martha Minow that the language of rights functions as a tool for resistance and change; Making All the Difference: Inclusion, Exclusion, and American Law (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990). ↵

- Festiner, Abel, and Sarat, “Emergence and Transformation of Disputes,” 632, 637. ↵

- Youjin Shin, Nick Kirkpatrick, Catherine D’Ignazio, and Wonyoung So, “Columbus Monuments are Coming Down But He is Still Being Honored in 6,000 Places Across the U.S., Here’s Where,” Washington Post, October 11, 2021. ↵

- William Elroy Curtis, Christopher Columbus: His Portraits and His Monuments; A Descriptive Catalogue (Chicago: W. H. Lowdermilk, 1893). ↵

- Paul Heike, “Christopher Columbus and the Myth of Discovery,” in The Myths that Made America: An Introduction to American Studies (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2014), 57. ↵

- Washington Irving, A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (London: John Murray, 1828), 10, quoted in Heike, “Christopher Columbus and the Myth of Discovery,” 58. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 57. ↵

- Aaron Goodrich, A History of the Character and Achievements of the So-Called Christopher Columbus (New York: D. Appleton, 1874; repr. London: Forgotten Books, 2018); Justin Winsor, Christopher Columbus and How He Received and Imparted the Spirit of Discovery (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1892). ↵

- Laura E. Ruberto and Joseph Sciorra, “Recontextualizing the Ocean Blue: Italian Americans and the Commemoration of Columbus,” Process: A Blog for American History, October 4, 2017, http://www.processhistory.org/recontextualizing-the-ocean-blue. ↵

- “Statue Idea of Professor,” Post Standard, October 13, 1934, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse. ↵

- Timothy Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory: Christopher Columbus and the Rewriting of the National Origin Myth (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 110. ↵

- Peter G. Vellon, A Great Conspiracy Against Our Race: Italian Immigrant Newspapers and the Construction of Whiteness in the Early Twentieth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 3, quoted in Ruberto and Sciorra, “Recontextualizing the Ocean Blue.” ↵

- “Statue Idea of Professor.” ↵

- Dick Case, “Cultures Butt Heads in Columbus Circle,” Herald-Journal, October 16, 1991, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse. ↵

- “Celebrating Cruelty of Columbus Divides Us (Your Letters),” Syracuse.com, October 9, 2020. As Thomas Kubal explains, many people in the United States supported Mussolini and his fascist movement before 1940 (Cultural Movements and Collective Memory, 104). ↵

- “Statue Idea of Professor.” ↵

- “400 Mark End of Columbus Statue Drive: Close of Long Struggle is Celebrated at Banquet,” Post Standard, October 13, 1934, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse. ↵

- Dwight James Baum, The Work of Dwight James Baum, Architect, ed. William Morrison (New York: Acanthus, 2008). ↵

- Heike, “Christopher Columbus,” 61. ↵

- Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory, 34–35. ↵

- “Statue’s Designs Symbolize Events of Navigator’s Life,” Post Standard, October 13, 1934, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages. ↵

- John C. Ewers, The Emergence of the Plains Indians as the Symbol of the North American Indian (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1965). ↵

- Ewers, Emergence of the Plains Indians. ↵

- Bruce Watson, “George Catlin’s Obsession,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2002, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/george-catlins-obsession-72840046. ↵

- Curtis, Christopher Columbus, 60–61. ↵

- “Statue’s Designs Symbolize Events of Navigator’s Life.” ↵

- Curtis, Christopher Columbus, 60–61. ↵

- Curtis, Christopher Columbus, 60–61. ↵

- Goodrich, A History of the Character and Achievements of the So-Called Christopher Columbus; Winsor, Christopher Columbus. ↵

- Frank J. Cavaioli, “Randolph Rogers and the Columbus Doors,” Italian Americana 17, no. 1 (Winter 1999): 8. ↵

- Cavaioli, “Randolph Rogers and the Columbus Doors,” 10–11. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 123. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 124. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 125. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 157–58. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 213. ↵

- The Christopher Columbus Monument in San Juan, Puerto Rico, was exceptional in this regard since the artist managed to fit all six Indigenous people—men and women—into his bas-relief of Columbus’s arrival at the Spanish court in 1893. ↵

- Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, 212. ↵

- Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate.” ↵

- Adelle M. Banks, “Stolen Heads Found in Snow Warehouse,” Orlando Sentinel, October 10, 1989. ↵

- Gary Gerew, “Heads Home: Monument’s Missing Parts Will Stay Crated For Now,” Herald-Journal, October 26, 1989. ↵

- Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory, 52. ↵

- Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory, 135–37. ↵

- Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me. ↵

- Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate.” ↵

- Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate.” ↵

- Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate.” ↵

- Sean Kirst, “Restoring Columbus, State Agency: Monument Work Restoration OK,” Post Standard, July 29, 1991, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse. ↵

- Erika Doss, “The Process Frame: Vandalism, Removal, Re-siting, Destruction,” in A Companion to Public Art, ed. Cher Krause Knight and Harriet F. Senie (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), 407. ↵

- Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd, “Joiri Minaya’s Cloaking of the Statue of Christopher Columbus,” Revista: Harvard Review of Latin America 20, no. 3 (Spring/Summer 2021), https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/joiri-minayas-cloaking-of-the-statue-of-christopher-columbus. ↵

- Nicole Kappatos, “The Story of the Christopher Columbus Statue in Byrd Park,” Richmond Times Dispatch, June 9, 2020, https://richmond.com/from-the-archives/from-the-archives-the-story-of-the-christopher-columbus-statue-in-byrd-park/article_6ff6eb6c-2fe9-11e5-8c16-9ff946830c22.html. ↵

- Kirst, “Restoration Sparks Debate.” ↵

- “Columbus As He Was: Blotting an Unhappy Event from the Record is an Affront to Historical Accuracy,” Post Standard, June 12, 1991, Monuments, Markers and Tablets in Syracuse. ↵

- Ned Kaufman, Place, Race, and Story: Essays on the Past and Future of Historic Preservation (New York: Routledge, 2009), 64–65. ↵

- Baker, “Walsh to Remove Syracuse’s Columbus Stature, Rename Columbus Circle.” ↵

- Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 4. ↵

- Shin, Kirkpatrick, D’Ignazio, and So, “Columbus Monuments are Coming Down.” ↵

- For more on the removal of Confederate monuments, see Katherine Poole-Jones, “Historical Memory, Reconciliation, and the Shaping of the Postbellum Landscape: The Civil War Monuments of Forest Park, St. Louis,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9765; and Sarah Beetham, “Confederate Monuments: Southern Heritage or Southern Art?” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9844. ↵

- Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory, 36. ↵

- Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory, 47–48. ↵

- Ruberto and Sciorra, “Recontextualizing the Ocean Blue.” ↵

- Case, “Cultures Butt Heads in Columbus Circle.” ↵

- Tim Knauss, “Syracuse Mayor Ben Walsh Can’t Remove Downtown Christopher Columbus Statue, Judge Rules,” Syracuse.com, March 11, 2022. ↵

- Daniel Wohler, “Downtown Committee of Syracuse Receives 500K through New York Main Street Grant,” CNY Central, December 13, 2017. ↵

- I borrow the term “cognitive map” from Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960). ↵

- Richard Dyer, White: Essays on Race and Culture (New York: Routledge, 1997). ↵

- Richard Dyer, “The Matter of Whiteness,” in White Privilege: Essential Readings on the Other Side of Racism, ed. Paula S Rothberg (New York: Worth, 2005), 12. ↵

- Stephen Jay Gould demonstrates that the Apollo Belvedere was an antique sculpture associated with whiteness; The Mismeasure of Man (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 33. ↵

- Upton, What Can and Can’t Be Said. ↵

- “It Stays!” Keep the Columbus Monument (blog), March 11, 2022, https://columbusmonumentsyracuse.com. ↵

About the Author(s): Kristina Borrman is Assistant Professor of Social Justice in the Built Environment, School of Design and Construction, at Washington State University.