Obligations to the Local: Solidarity as Method in LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Last Cruze

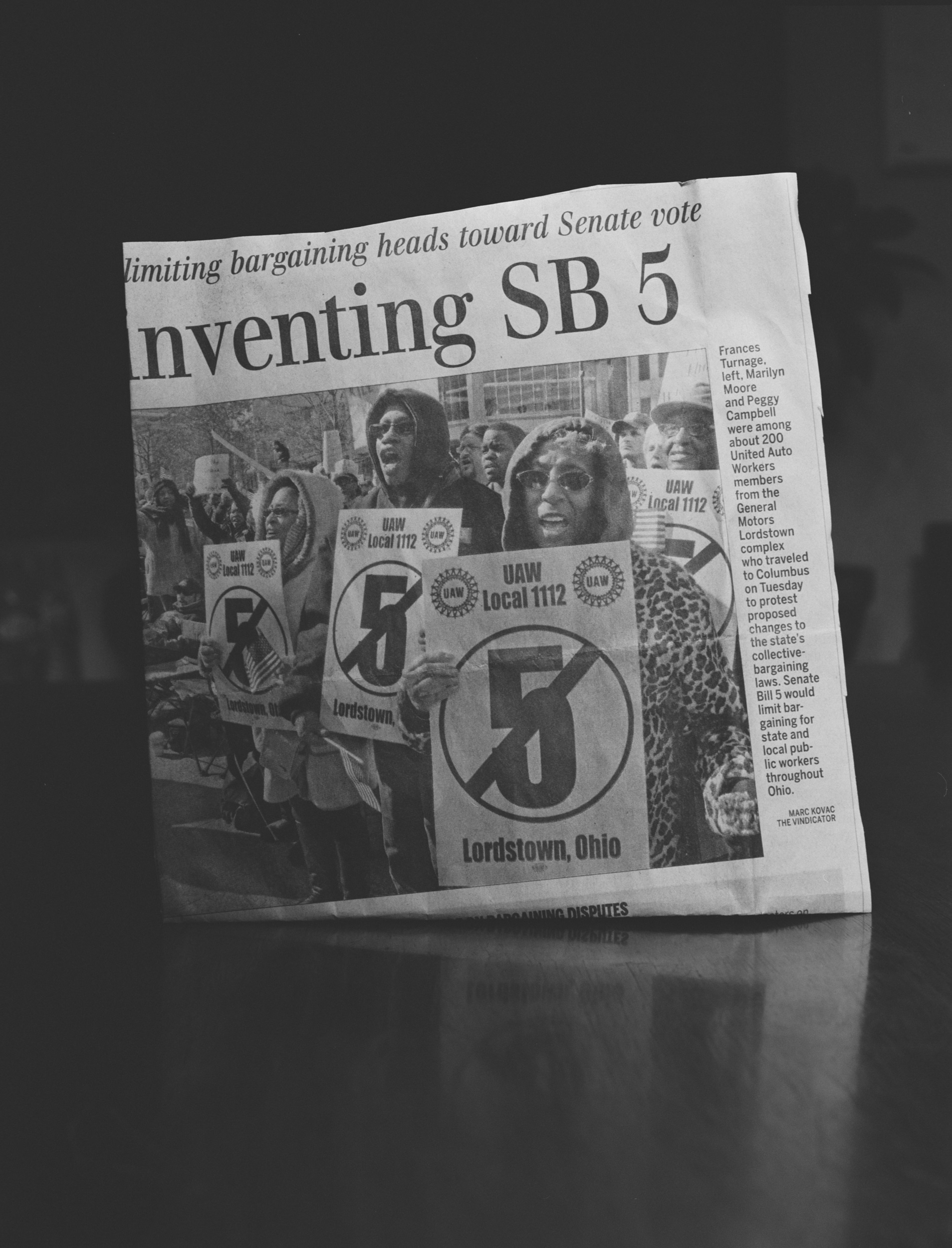

In November 2019, Pamela Brown, Marilyn Moore, and Frances Turnage, three longtime members of the United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 1112 Women’s Committee, held a public discussion with photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier (b. 1982) about their experiences in the labor movement. The conversation formed part of the public programming surrounding Frazier’s documentary project The Last Cruze, then installed at the Renaissance Society in Chicago. At one point, Frazier described an interaction she had earlier that year while sitting in Turnage’s living room. Turnage had pulled out a binder of newspaper clippings, one of which included a photograph of her alongside two of her fellow Local 1112 members in Columbus, Ohio, holding union signs in their hands; the trio of women stood amid a crowd of people protesting a piece of 2011 state legislation that would strip public employees of their collective-bargaining rights. Frazier produced a photograph of the clipping as if it were an icon, balanced upright on Turnage’s dining-room table, starkly illuminated against a near-black background (fig. 1). Such reverent treatment of this humble material signals Frazier’s recognition of the scrapbook as a site where personal stories are crafted and relayed to others through storytelling. The fact that the book contains scraps from Turnage’s union history is also significant. By sharing this object with Frazier and, by extension, allowing her to share it with her viewers, Turnage initiates Frazier into a local history long sustained by relations of obligation and struggle.

Frazier’s The Last Cruze embeds viewers in the lives of Lordstown, Ohio’s multiracial working class during a moment of crisis. Shortly before beginning the project in 2019, General Motors (GM) announced they would be “unallocating” their Lordstown plant, effectively ending automobile production at a site that had been active for over fifty years. To continue their employment at GM and save their pensions, members of UAW Local 1112, the plant’s labor union, had to make a painful choice: whether or not to accept a short-notice work transfer to a different location. In some cases, this transfer meant moving hundreds of miles away, uprooting familial, social, and community networks established over generations. Frazier’s photographs depict the Lordstown community through a series of intimate portraits of workers and their families paired with excerpts from interviews she recorded with them during this tumultuous period. When the series made its debut as a photo essay published in the May 1 edition of the New York Times Magazine, and during its subsequent installation at the Renaissance Society, many critics viewed the struggle of Local 1112 and its allies as emblematic of a political economy transformed by decades of deindustrialization in countries throughout the Global North. Frazier’s subject seemed to hold other important lessons for the Trump era, in which the composition and political allegiance of the working class emerged as a topic of heated debate among many commentators.

I first began thinking deeply about Frazier’s project in October 2021, a month that had popularly been dubbed “Striketober” to designate the surprising wave of labor actions in the United States at the time; it was followed by “Strikevember” and “Strikesgiving.” Even though the month of December failed to generate a similar moniker, such actions have not abated. It is clear that we are in the middle of what sociologist Gabriel Winant identifies as a “revival in working-class militancy.”1

Against this backdrop, I look to Frazier’s depiction of Lordstown’s Local 1112 as a prism through which to understand “the local” as a category constituted through specific kinds of social and political relationships. I argue that Frazier’s project exemplifies what I call an “art of solidarity“ through its methodological approach to documentary production that relies on relations of local obligation—in this case, to the members of the union who are the project’s subjects and collaborators. Whereas solidarity is commonly understood as an alliance of shared sentiments, I posit a more robust conception of solidarity that views it as a normatively defined duty for a community of individuals to act in unison. Sentiments, in other words, are secondary to action. In the case of The Last Cruze, this obligatory relation extends to the photographer as well. After demonstrating how Frazier’s project intervenes in a long genealogy of photographers’ work concerned with the representation of local political economies, I draw on recent strands of political theory to tease out this more precise definition of solidarity within the context of UAW Local 1112.

Some of Frazier’s first photographs from the project appeared in the New York Times Magazine as part of an article on the Lordstown GM plant. It opens with an aerial photograph (fig. 2) Frazier took of the residential neighborhood immediately adjacent to GM’s sprawling facility. While such aerial photographs typically serve a simple mapping function, Frazier’s example subtly attunes viewers to the economic relations that structure this company town. Viewers of the photograph look down upon a triangular tract of residential development, which funnels their gaze to the lower corner of the print. The snowy landscape and bare trees throw the rows of modestly sized, neatly placed homes into stark relief. In contrast to the visual plenitude of the residential streets, along the upper register of the frame runs a series of nearly empty lots that adjoin GM’s 650-acre Lordstown campus. The visual instability of this composition—an inverted, slightly skewed triangular shape—finds a conceptual corollary in the instability that accompanies capitalism’s unceasing search for profit on a world scale. Within the local/global dyad that structures our understanding of global capitalism, the local emerges as the place where capital temporarily lands in its efforts to assemble labor for the creation of surplus value. Benjamin Young draws on this understanding of capital’s disruptive flows, the way it establishes local social relations before moving to new sites of extraction and profit, to describe the local impact of GM’s decision to close the Lordstown plant, observing, “In contrast with the mobility of capital on which economic globalization depends, The Last Cruze maps the web of relations that tie those depicted to this particular place, and the damage to that social fabric that will ensue when it is rent apart.”2 Frazier’s aerial photograph therefore confronts viewers with much more than a physical record of geographical space; it confronts them with a conceptual representation of a political economy, as well.

The visual prominence of the residential neighborhood in Frazier’s aerial photograph also signals the primary focus of her photographic intervention in Lordstown: the private spaces occupied by workers rather than their sites of economic production. Early in the twentieth century, playwright Bertolt Brecht inaugurated a debate over photography’s ability to represent the forces of his own era’s political economy when he famously claimed, “A photograph of the Krupp works or the AEG [General electricity company] reveals next to nothing about these institutions.”3 Of course, Brecht knew what happened inside the factory walls just as well as Frazier did a century later: the industrial production of goods and commodities. What Brecht meant to underscore, however, was the desire to understand the conditions of labor within the factory and, by extension, to grasp how “delivering the goods” under capitalism requires society to organize labor in specific locations. Reflecting on her time growing up in Braddock, Pennsylvania, Frazier recalls, “I didn’t really understand why we were next to this factory, caught in the shadow not only of the Edgar Thomson steel plant, but also caught in the shadow of Andrew Carnegie. What does that mean to have to measure yourself, or try to be seen, through an industrial capitalist?”4 While extending Brecht’s line of questioning, Frazier’s work in The Last Cruze does not rely on the factory itself as its operational center. In fact, GM barred Frazier from accessing the Lordstown facility and threatened her with violence if she attempted to access the premises herself.5 The members of Local 1112 responded by providing her with more intimate access: they unanimously voted to allow Frazier to photograph inside the union hall and among the members. This kind of obligatory democratic relationship with local forces and organizations represents an integral methodological element of Frazier’s art of solidarity that will be explored below. For now, what remains important is the sidelining of the factory as photographic site in favor of a more intimate and private mode of picture making situated within the portrait genre. The photographs and interviews Frazier produced with idled Lordstown workers as they gather at the union hall, their homes, and other establishments represent how local bonds of solidarity are formed in the face of a political economy bent on their destruction.

The insights of radical geographers David Harvey and Ruth Wilson Gilmore are instructive on the subject of destructive political economies and the social relations available to combat them. In a public conversation at the Renaissance Society scheduled to coincide with the exhibition of The Last Cruze, Frazier prompted Harvey to share his thoughts on the corporate euphemism deployed by GM to describe the new status of the Lordstown facility. “What does it mean to be unallocated?” Harvey asks rhetorically, before continuing:

In a funny way, it says something about the contemporary world that the powers that be don’t know where to put all these people so they’re just simply saying they’re disposable. They are un-allocatable, and so let’s call them unallocated and let the workers get on with trying to survive in that condition.6

Gilmore provides a more precise term for identifying this condition. For Gilmore, “relative surplus population” describes the idled and unemployed workers who must “wait, migrate, or languish until—if ever—new opportunities to sell their labor power emerge.”7 In her pioneering study Golden Gulag, Gilmore identifies a prison-building boom and accompanying rise in mass incarceration as California’s “solution” to this surplus problem. “Make no mistake,” Gilmore cautions, “prison building was and is not the inevitable outcome of these surpluses.”8 While the story of Lordstown is still being written, the bonds of solidarity built by workers and captured by Frazier offer one avenue for combatting such social violence.

Frazier’s integration of photography, portraiture, and political economy in The Last Cruze intervenes in a long history of similar efforts among committed photographers. A project by the German photographer August Sander (1876–1964), Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the twentieth century), begun in the 1920s, sought to construct an encyclopedic catalogue of the social ordering of the Weimar Republic. With great technical proficiency, Sander produced hundreds of portraits, which he organized into various portfolios according to social class and profession, ranging from farmers and skilled tradesmen to professional, intellectual, and political stations, resulting in an all-encompassing “social ontology.”9 In a slightly different vein, American Paul Strand (1890–1976) produced a series of photobooks focused on representing specific, often rural communities through portraiture, landscape, and candid scenes of everyday life. The composition of a family portrait that Frazier took of Local 1112–member Trisha Brown in front of her home (fig. 3) contains strong echoes of Strand’s 1953 portrait of the Lusetti family in Luzzara, Italy (fig. 4). Contemporary Spanish photographer and critic Jorge Ribalta views Strand’s interest in small agrarian communities in light of the photographer’s left-wing political sympathies:

The photographs aimed at expressing the dignity of vernacular forms of labor, creativity, and resistance in such communities, all rooted in different specific cultural and physical geographies. Throughout these books, made in New England, the Hebrides, France, or Italy, Strand seemed to demonstrate that the spontaneous social production of communism is a kind of pre-political and universal basic human condition, most accessible in more or less remote rural pre-modern parts of the world.10

Ribalta’s reading ultimately suggests that the political economy that emerges across Strand’s midcentury pictures is conditioned by his sublimated political desire after his traumatic experience of McCarthyite repression in the United States. The crux of what some refer to as Strand’s “romantic anti-capitalism” lay in his focus on the locales seemingly untouched by the forces of global capitalism.11

In contrast to the “social ontology” of Sander and the “romantic anti-capitalism” of Strand, Frazier draws more explicitly on the legacy of photographer Gordon Parks (1912–2006). “Parks’s American Gothic was one of the first images that I saw by him . . . and it shook me up,” she recalled in a 2017 interview, continuing, “That image really pushed me to start to become more accountable and more responsible to what I wanted to say.”12 Parks took his now-iconic photograph of Ella Watson, an African American janitor who worked in a government office building in Washington, DC, mop and broom in hand, posed in front of an American flag in 1942. Parks spent two years photographing in the nation’s capital under the direction of Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration. Photo historian Deborah Willis observes how Parks made images about the “social implications of the underemployed and their children,” a point of view that distinguished him from the city’s studio photographers and photojournalists of the time who catered mainly to the upper and middle classes.13 What Parks ultimately provides to a photographer like Frazier is an example of how to visually confront the oppressive configurations of racial capitalism, described by Gilmore as the ways in which racism enshrines the economic inequalities required by capitalism.14

A close look at Frazier’s portrait of Crystal Carpenter and her family (fig. 5) from The Last Cruze helps illustrate how UAW Local 1112 historically served as a bulwark against this otherwise oppressive political economy through its commitment to Civil Rights unionism. A neat row of five dining chairs arranged in Carpenter’s living room bisect the photograph from edge to edge. Her uncle Arthur Clinkscale sits in the middle chair, occupying the center of the frame. Behind his shoulders stand Crystal and her cousin Sherria, joined on either side by their husbands, Theodore and Jason. The family stares intently into Frazier’s camera, each member’s hands on or around one another’s shoulders, linking them together as a unit. Draped across the empty chairs that sit on either side of Clinkscale are UAW shirts that commemorate important movements, committees, and historical moments in the union’s history. “Mobilizing for Justice Team” and “Economic Justice to Win” read two shirts, while another memorializes the end of the epochal Flint sit-down strikes in February 1937. In Frazier’s photographs, these vernacular memorials constitute a kind of historical palimpsest that points toward the UAW’s long history of struggling for social, racial, and economic justice. Indeed, in the expansive catalogue of The Last Cruze, Frazier underscores this history of intersecting struggles by including a thirty-page timeline of the UAW from its founding in 1935 to the present, with particular attention to the organization’s active participation in the long Civil Rights Movement. The photograph provides a visual distillation of a generations-long struggle sustained at the local level through relations of solidarity, mediated through union politics and labor organizing.

This mode of generational picturing is not new to Frazier. Her first major project, The Notion of Family, centers on her own family and three generations of Braddock, Pennsylvania, women: her grandmother, her mother, and herself. Over the preceding decades, these women have experienced Braddock’s prosperous years as a booming steel town in the 1950s, its economic decline during the 1970s, and its contemporary impoverishment and environmental degradation.15 Frazier’s photographs in The Notion of Family not only provide an intimate portrait of three generations of working-class women but a historical portrait of a local political economy and its amplification of racialized poverty and environmental neglect. Describing The Notion of Family, art historian Laura Wexler observes, “The images manifest trust in the family as an organizing principle.”16 The Last Cruze represents a continuation of this organizing principle, although with the following slight transformation: it is not just trust in the family that drives this project but trust in the union local, as well. These two principles are not nearly as divergent as they may seem. Those with involvement in the labor movement recognize vocabulary that connects unionism with kinship. Union members often speak of their “brothers and sisters” or the increasingly common gender-neutral “siblings.” Turnage, one of Frazier’s collaborators in The Last Cruze who started working at GM in 1972, remarked that “we felt like LaToya was just another UAW sister to talk to.”17 The implication of this kinship language is that union members have an obligation to stand with and support other members of the organization, even in times of interpersonal disagreement. There is, in general, a recognition that important decisions are made communally and, in the best-case scenario, democratically to ensure that the sacrificial aspects of collective obligation do not undermine the enterprise.

Understanding solidarity in this regard requires us to dispense with the more colloquial uses of the term that conceives of its power in an affective register. Walter Benn Michaels and David Zamora write of the relationship Frazier’s pictures have to their beholder, defining what they view as her work’s “class aesthetic”:

The portrait of a class doesn’t demand solidarity any more than it demands compassion; it is, in a certain sense, more abstract than that—interested neither in individual subjectivities nor in what David Levi Strauss calls “collective subjectivities.” If we want to get rid of the class system, the question of which class we belong to is ultimately irrelevant. What’s required, in other words, is neither that the middle class feel compassion for workers nor that it turn that compassion into an identificatory solidarity.18

In these lines, Michaels and Zamora tap into a long history of criticism aimed at the oftentimes compensatory relationship between social documentary and capitalism.19 Such criticism posits that social documentary serves to preserve the capitalist power structure through the work of professional reformers, who use photographs of working-class degradation in their appeals for the upper and middle classes to ameliorate some of the more oppressive elements of capitalist industry. My own conception of solidarity departs rather dramatically from the one implied by Michaels and Zamora. Instead, I build upon what Ariella Aïsha Azoulay calls the “civil contract of photography” and her contention that the photographic event is capable of forming partnerships beyond the strictures of governmental power in a framework that is “neither constituted nor circumscribed by the sovereign [ruling powers].”20

What, then, is solidarity, beyond the alignment of sentiments, attitudes, or opinions among individuals? Political theorist Avery Kolers draws attention to two distinctive elements. First, she notes that solidarity is “a type of action.”21 Sentiments, attitudes, and opinions must be acted upon, not simply acknowledged. Second and more important, this action must occur while “working with others for common political aims, paradigmatically in a context of incompletely shared interests.”22 This point is worth pausing on, since Kolers’s insistence on a context of incomplete interests challenges the centrality of individual agency within liberal humanist conceptions of political action, at least when this agency becomes embedded within solidarity groups. Kolers explains that for solidarity to be operative within a group, bonds of mutual trust and support must be strengthened to the extent that individual agency can, at times, be “compromised and reshaped” to fit the intended goals of the group.23 Frazier underscores this form of mutual trust in relations of solidarity when she describes her experience working with Local 1112: “What I saw when I went in there were people who it didn’t matter if you voted or didn’t vote, or voted Trump or didn’t, voted for Hillary, or wanted Bernie. People refer to each other as ‘brother’ and ‘sister’ regardless of politics.”24

There are further key nuances to solidarity that derive from the concept’s normative aspects. Political theorist Ashley Taylor, for example, separates what she terms “expressional solidarity” from “robust solidarity.” The former is premised on an agreement among all members of a solidarity group who are motivated to act in unison “but who do not have a solidary obligation to act.”25 In a robust solidarity, on the other hand, all members are obligated to act in unison so as not to undermine the group aims.26 Taylor recognizes that the stress she places on relations of obligation brings moral and normative considerations into relations of solidarity. Obligation does not necessarily preclude an individual from acting outside the group interests, although it would likely lead other group members to ascribe blame to the offending individual. “Scab,” the derogatory term used to describe anyone who betrays a planned work stoppage, is evidence of solidarity’s moral, normative, and obligatory aspects described above. Turnage, whose scrapbook image I described at the outset of this essay, explains, “Any time our union calls for retirees or anybody to come out and get on a bus to protest, you can believe that me and Marilyn and Delores are going to be on the front line.”27 The preserved scrap of newspaper Turnage shared with Frazier testifies to these elements of solidarity.

Moving beyond a definition of solidarity that centers affective desire and aspiration to one grounded in the moral and normative obligation to act in certain unified ways helps recast the significance of Frazier’s collaborative documentary enterprise in Lordstown. Before initiating The Last Cruze, Frazier placed the fate of the project in the hands of Local 1112, whose permission was necessary to responsibly capture any version of their ongoing struggle.28 By abrogating the act of individual decision-making and the prerogatives of autonomous aesthetic production, Frazier opens up a relation of solidarity with her subjects, allowing her to more effectively insert her documentary practice into already existing political struggles. Rick Smith, the financial secretary of Local 1112, remarked that, “[Frazier] did more for us than I think anybody else could have. . . . I’ve never seen somebody get as involved. And I can’t put it into words.”29

Considering Smith’s comments on the commitment of outsiders to the union’s struggle, it is fitting that Frazier closes the publication version of The Last Cruze with her portrait of Werner Lange (fig. 6), a retired sociology professor and community activist, alongside his short essay “Taking a Stand Against Corporate Cruelty.” For forty-five days in early 2019, Lange held vigil on the side of Ellsworth Bailey Road, which led to the Lordstown GM facility, offering workers a raised fist salute as they arrived at and left the factory. Frazier explains her choice of ending the publication with Lange, stating, “I intentionally put [Lange] at the end because he was the one-standing witness who carried out a 45-day vigil on behalf of the autoworkers in Lordstown. It is by design that The Last Cruze ends with a call for moral and spiritual revival, class-unity and, above all, for an agape love.”30 This turn to agape, to spiritual love, would seem to send us back into the throes of a merely affective solidarity. I imagine, though, that what Frazier has in mind with this reference is something closer to the revolutionary love described by the late bell hooks, who wrote of love as “an action rather than a feeling.”31

In The Last Cruze, Frazier endeavors to tell a local story about Lordstown that holds a set of grander lessons about the nature of class struggle from the second half of the twentieth century into the present. Her representation of this local story is refined through her relation to the workers and families of UAW Local 1112. An attunement to histories of labor, to related visualizations of political economy, and to the concept of solidarity that relies on obligation and action helps to throw the unique significance of Frazier’s project into relief. As struggles for social, economic, and racial justice continue to deepen in the wake of ongoing pandemic politics, Frazier shows how an art of solidarity can fortify our agape love in the face of capitalism’s worst depredations.

Cite this article: Samuel Dylan Ewing, “Obligations to the Local: Solidarity as Method in LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Last Cruze,” in “Art History and the Local,” In the Round, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 8, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.13162.

PDF: Ewing, Obligations to the Local

Notes

- Gabriel Winant, “Strike Wave,” Sidecar, November 25, 2021, https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/strike-wave. ↵

- Benjamin Young, “Photography at the Factory Gates,” in The Last Cruze, ed. LaToya Ruby Frazier (Chicago: Renaissance Society, 2020), 237. ↵

- Bertolt Brecht, quoted in Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” in The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Rodney Livingstone, Howard Eiland, et al. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008), 193. ↵

- Kellie Jones and LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Witness: The Unfinished Work of the Civil Rights Movement,” Aperture, no. 226 (Spring 2017): 21. ↵

- Young, “Photography at the Factory Gates,” 248. ↵

- David Harvey and LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Conversation,” in Frazier, The Last Cruze, 314. ↵

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prison, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 71. ↵

- Gilmore, Golden Gulag, 88. ↵

- Benjamin Buchloh, “Residual Resemblance: Three Notes on the End of Portraiture,” in Face-Off: The Portrait in Recent Art, ed. Melissa E. Feldman (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1994), 57. ↵

- Jorge Ribalta, “The Strand Symptom: A Modernist Disease?” Oxford Art Journal 38, no. 1 (2015): 67. ↵

- See Andrew Hemingway, “Paul Strand and Twentieth-Century Americanism: Varieties of Romantic Anti-Capitalism,” Oxford Art Journal 38, no. 1 (2015): 1–17. ↵

- Jones and Frazier, “Witness,” 25. ↵

- Deborah Willis, “Gordon Parks and the Image of the Capital City,” in Visual Journal: Harlem and D.C. in the Thirties and Forties, ed. Deborah Willis and Jane Lusaka (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), 179. ↵

- Antipode online, “Geographies of Racial Capitalism with Ruth Wilson Gilmore—An Antipode Foundation Film,” June 1, 2020, video, 16:18, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CS627aKrJI. ↵

- Gabriel Winant offers a cogent history of this economic transformation in his recent book The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021). ↵

- Laura Wexler, “A Notion of Photography,” in A Notion of Family, ed. LaToya Ruby Frazier (New York: Aperture, 2014), 144. ↵

- Pamela Brown, Marilyn Moore, Frances Turnage, UAW Local 1112 Women’s Committee, and LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Conversation,” in Frazier, The Last Cruze, 181. ↵

- Walter Benn Michaels and Daniel Zamora, “Chris Killip and LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Promise of a Class Aesthetic,” Radical History Review, no. 132 (October 2018): 38. Emphasis added. ↵

- See, for example, Martha Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography),” in Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 151–206. ↵

- Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone, 2008), 23. ↵

- Avery H. Kolers, “Dynamics of Solidarity,” Journal of Political Philosophy 20, no. 4 (2012): 367. Emphasis added. ↵

- Kolers, “Dynamics of Solidarity,” 367. Emphasis added. ↵

- Kolers, “Dynamics of Solidarity,” 366. ↵

- David Green and Rick Smith, UAW Local 1112, and LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Conversation,” in Frazier, The Last Cruze, 172. ↵

- Ashley E. Taylor, “Solidarity: Obligations and Expressions,” Journal of Political Philosophy 23, no. 2 (2015): 130. Emphasis added. ↵

- Taylor, “Solidarity,” 130. ↵

- Green, Smith, and Frazier, “Conversation,” 185. ↵

- Frazier described the significance of this process in a public event that accompanied The Last Cruze installation in Chicago: “I’m 37 years old and I had never seen democracy in action until the day I went inside Lordstown Local 1112.” Green, Smith, and Frazier, “Conversation,” 172. ↵

- Green, Smith, and Frazier, “Conversation,” 173. ↵

- Lynn Nottage and LaToya Ruby Frazier, “Conversation,” in Frazier, The Last Cruze, 370. ↵

- bell hooks, All About Love (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), 13. ↵

About the Author(s): Samuel Dylan Ewing is an independent curator and scholar.